A Synthesis of Geophysical and Biological Assessment to Determine Restoration Priorities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kells Bay Nursery

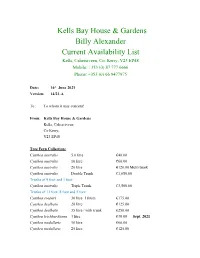

Kells Bay House & Gardens Billy Alexander Current Availability List Kells, Cahersiveen, Co. Kerry, V23 EP48 Mobile: +353 (0) 87 777 6666 Phone: +353 (0) 66 9477975 Date: 16th June 2021 Version: 14/21-A To : To whom it may concern! From: Kells Bay House & Gardens Kells, Caherciveen Co Kerry, V23 EP48 Tree Fern Collection: Cyathea australis 5.0 litre €40.00 Cyathea australis 10 litre €60.00 Cyathea australis 20 litre €120.00 Multi trunk Cyathea australis Double Trunk €1,650.00 Trunks of 9 foot and 1 foot Cyathea australis Triple Trunk €3,500.00 Trunks of 11 foot, 8 foot and 5 foot Cyathea cooperi 30 litre 180cm €175.00 Cyathea dealbata 20 litre €125.00 Cyathea dealbata 35 litre / with trunk €250.00 Cyathea leichhardtiana 3 litre €30.00 Sept. 2021 Cyathea medullaris 10 litre €60.00 Cyathea medullaris 25 litre €125.00 Cyathea medullaris 35 litre / 20-30cm trunk €225.00 Cyathea medullaris 45 litre / 50-60cm trunk €345.00 Cyathea tomentosisima 5 litre €50.00 Dicksonia antarctica 3.0 litre €12.50 Dicksonia antarctica 5.0 litre €22.00 These are home grown ferns naturalised in Kells Bay Gardens Dicksonia antarctica 35 litre €195.00 (very large ferns with emerging trunks and fantastic frond foliage) Dicksonia antarctica 20cm trunk €65.00 Dicksonia antarctica 30cm trunk €85.00 Dicksonia antarctica 60cm trunk €165.00 Dicksonia antarctica 90cm trunk €250.00 Dicksonia antarctica 120cm trunk €340.00 Dicksonia antarctica 150cm trunk €425.00 Dicksonia antarctica 180cm trunk €525.00 Dicksonia antarctica 210cm trunk €750.00 Dicksonia antarctica 240cm trunk €925.00 Dicksonia antarctica 300cm trunk €1,125.00 Dicksonia antarctica 360cm trunk €1,400.00 We have lots of multi trunks available, details available upon request. -

Waipa District Development and Subdivision Manual

Table of Contents Waipa District Development and Subdivision Manual Waipa District Development and Subdivision Manual 2015 Page 1 How to Use the Manual How to Use the Manual Please note that Waipa District Council has no controls over the way your electronic device prints the electronic version of the Manual and cannot guarantee that it will be consistent with the published version of the Manual. Version Control Version Date Updated By Section / Page # and Details 1.0 November 2012 Administrator Document approved by Council. 2.0 August 2013 Development Engineer Whole document updated to reflect OFI forms received. 2.1 September 2013 Development Engineer Whole document updated 2.2 August 2014 Development Engineer Whole document updated to reflect feedback from internal review. 2.3 December 2014 Development Engineer Whole document approved by Asset Managers 2.4 January 2015 Administrator Whole document renumbered and formatted. 2.5 May 2015 Administrator Document approved by Council. Page 2 Waipa District Development and Subdivision Manual 2015 Table of Contents Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ 3 Part 1: Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 5 Part 2: General Information ............................................................................................................ 7 Volume 1: Subdivision and Land Use Processes -

TAXON:Dicksonia Squarrosa (G. Forst.) Sw. SCORE

TAXON: Dicksonia squarrosa (G. SCORE: 18.0 RATING: High Risk Forst.) Sw. Taxon: Dicksonia squarrosa (G. Forst.) Sw. Family: Dicksoniaceae Common Name(s): harsh tree fern Synonym(s): Trichomanes squarrosum G. Forst. rough tree fern wheki Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 11 Sep 2019 WRA Score: 18.0 Designation: H(HPWRA) Rating: High Risk Keywords: Tree Fern, Invades Pastures, Dense Stands, Suckering, Wind-Dispersed Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 n Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 ? outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 n 402 Allelopathic 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable to grazing animals y=1, n=-1 n 405 Toxic to animals y=1, n=0 n 406 Host for recognized pests and pathogens 407 Causes allergies or is otherwise toxic to humans 408 Creates a fire hazard in natural ecosystems y=1, n=0 y 409 Is a shade tolerant plant at some stage of its life cycle y=1, n=0 y Creation Date: 11 Sep 2019 (Dicksonia squarrosa (G. -

Pteridologist 2007

PTERIDOLOGIST 2007 CONTENTS Volume 4 Part 6, 2007 EDITORIAL James Merryweather Instructions to authors NEWS & COMMENT Dr Trevor Walker Chris Page 166 A Chilli Fern? Graham Ackers 168 The Botanical Research Fund 168 Miscellany 169 IDENTIFICATION Male Ferns 2007 James Merryweather 172 TREE-FERN NEWSLETTER No. 13 Hyper-Enthusiastic Rooting of a Dicksonia Andrew Leonard 178 Most Northerly, Outdoor Tree Ferns Alastair C. Wardlaw 178 Dicksonia x lathamii A.R. Busby 179 Tree Ferns at Kells House Garden Martin Rickard 181 FOCUS ON FERNERIES Renovated Palace for Dicksoniaceae Alastair C. Wardlaw 184 The Oldest Fernery? Martin Rickard 185 Benmore Fernery James Merryweather 186 FEATURES Recording Ferns part 3 Chris Page 188 Fern Sticks Yvonne Golding 190 The Stansfield Memorial Medal A.R. Busby 191 Fern Collections in Manchester Museum Barbara Porter 193 What’s Dutch about Dutch Rush? Wim de Winter 195 The Fine Ferns of Flora Græca Graham Ackers 203 CONSERVATION A Case for Ex Situ Conservation? Alastair C. Wardlaw 197 IN THE GARDEN The ‘Acutilobum’ Saga Robert Sykes 199 BOOK REVIEWS Encyclopedia of Garden Ferns by Sue Olsen Graham Ackers 170 Fern Books Before 1900 by Hall & Rickard Clive Jermy 172 Britsh Ferns DVD by James Merryweather Graham Ackers 187 COVER PICTURE: The ancestor common to all British male ferns, the mountain male fern Dryopteris oreades, growing on a ledge high on the south wall of Bealach na Ba (the pass of the cattle) Unless stated otherwise, between Kishorn and Applecross in photographs were supplied the Scottish Highlands - page 172. by the authors of the articles PHOTO: JAMES MERRYWEATHER in which they appear. -

1999 New Zealand Botanical Society

NEW ZEALAND BOTANICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER NUMBER 57 SEPTEMBER 1999 New Zealand Botanical Society President: Jessica Beever Secretary/Treasurer: Anthony Wright Committee: Bruce Clarkson, Colin Webb, Carol West Address: c/- Canterbury Museum Rolleston Avenue CHRISTCHURCH 8001 NEW ZEALAND Subscriptions The I999 ordinary and institutional subs are $18 (reduced to $15 if paid by the due date on the subscription invoice). The 1999 student sub, available to full-time students, is $9 (reduced to $7 if paid by the due date on the subscription invoice). Back issues of the Newsletter are available at $2.50 each from Number 1 (August 1985) to Number 46 (December 1996), $3.00 each from Number 47 (March 1997) to Number 50 (December 1997), and $3.75 each from Number 51 (March 1998) onwards. Since 1986 the Newsletter has appeared quarterly in March, June, September and December. New subscriptions are always welcome and these, together with back issue orders, should be sent to the Secretary/Treasurer (address above). Subscriptions are due by 28 February of each year for that calendar year. Existing subscribers are sent an invoice with the December Newsletter for the next year's subscription which offers a reduction if this is paid by the due date. If you are in arrears with your subscription a reminder notice comes attached to each issue of the Newsletter. Deadline for next issue The deadline for the December 1999 issue (Number 58) is 26 November 1999. Please forward contributions to: Dr Carol J. West, c/- Department of Conservation PO Box 743 Invercargill Contributions may be provided on an IBM compatible floppy disc (Word) or by e-mail to [email protected] Cover Illustration Plagiochila ramosissima with antheridial branches. -

Downloadable PDF Format On

Checklist of the New Zealand Flora Ferns and Lycophytes 2019 A New Zealand Plant Names Database Report © Landcare Research New Zealand Limited 2019 This copyright work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. Attribution if redistributing to the public without adaptation: "Source: Landcare Research" Attribution if making an adaptation or derivative work: "Sourced from Landcare Research" DOI: 10.26065/6s30-ex64 CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION Checklist of the New Zealand flora : ferns and lycophytes [electronic resource] / Allan Herbarium. – [Lincoln, Canterbury, New Zealand] : Landcare Research Manaaki Whenua, 2017- . Online resource Annual August 2017- ISSN 2537-9054 I.Manaaki Whenua-Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd. II. Allan Herbarium. Citation and Authorship Schönberger, I.; Wilton, A.D.; Brownsey, P.J.; Perrie, L.R.; Boardman, K.F.; Breitwieser, I.; de Pauw, B.; Ford, K.A.; Gibb, E.S.; Glenny, D.S.; Korver, M.A.; Novis, P.M.; Prebble, J.M.; Redmond, D.N.; Smissen, R.D.; Tawiri, K. (2019) Checklist of the New Zealand Flora – Ferns and Lycophytes. Lincoln, Manaaki Whenua-Landcare Research. http://dx.doi.org/10.26065/6s30-ex64 This report is generated using an automated system and is therefore authored by the staff at the Allan Herbarium and collaborators who currently contribute directly to the development and maintenance of the New Zealand Plant Names Database (PND). Authors are listed alphabetically after the fourth author. Authors have contributed as follows: Leadership: Wilton, Breitwieser Database editors: Wilton, Schönberger, Gibb Taxonomic and nomenclature research and review for the PND: Schönberger, Wilton, Gibb, Breitwieser, Brownsey, de Lange, Ford, Fife, Glenny, Novis, Perrie, Prebble, Redmond, Smissen Information System development: Wilton, De Pauw, Cochrane Technical support: Boardman, Korver, Redmond, Tawiri Contents Introduction....................................................................................................................................................... -

Dryopteris Filix-Mas (L.) Schott, in Canterbury, New Zealand

An Investigation into the Habitat Requirements, Invasiveness and Potential Extent of male fern, Dryopteris filix-mas (L.) Schott, in Canterbury, New Zealand A thesis Submitted in partial fulfilment Of the requirements for the Degree of Masters in Forestry Science By Graeme A. Ure School of Forestry University of Canterbury June 2014 Table of Contents Table of Figures ...................................................................................................... v List of Tables ......................................................................................................... xi Abstract ................................................................................................................ xiii Acknowledgements .............................................................................................. xiv 1 Chapter 1 Introduction and Literature Review ............................................... 1 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Taxonomy and ecology of Dryopteris filix-mas .......................................................... 2 1.2.1 Taxonomic relationships .................................................................................... 2 1.2.2 Life cycle ............................................................................................................... 3 1.2.3 Native distribution .............................................................................................. 4 1.2.4 Native -

RESEARCH Patterns of Woody Plant Epiphytism on Tree Ferns in New

BrockNew Zealand & Burns: Journal Woody of epiphytes Ecology (2021)of tree 45(1):ferns 3433 © 2021 New Zealand Ecological Society. 1 RESEARCH Patterns of woody plant epiphytism on tree ferns in New Zealand James M. R. Brock*1 and Bruce R. Burns1 1School of Biological Sciences, The University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland, New Zealand *Author for correspondence (Email: [email protected]) Published online: 13 January 2021 Abstract: Tree fern trunks provide establishment surfaces and habitat for a range of plant taxa including many understorey shrubs and canopy trees. The importance of these habitats for augmenting forest biodiversity and woody plant regeneration processes has been the subject of conjecture but has not been robustly assessed. We undertook a latitudinal study of the woody epiphytes and hemiepiphytes of two species of tree ferns (Cyathea smithii, Dicksonia squarrosa) at seven sites throughout New Zealand to determine (1) compositional variation with survey area, host identity, and tree fern size, and (2) the frequency of woody epiphyte and hemiepiphyte occurrence, in particular that of mature individuals. We recorded 3441 individuals of 61 species of woody epiphyte and hemiepiphyte on 700 tree ferns across the seven survey areas. All were facultative or accidental, with many species only ever recorded as seedlings. Epiphyte composition varied latitudinally in response to regional species pools; only two species occurred as woody epiphytes at every survey area: Coprosma grandifolia and Schefflera digitata. Five woody epiphyte species exhibited an apparent host preference to one of the two tree fern species surveyed, and trunk diameter and height were strong predictors of woody epiphyte and hemiepiphyte richness and diversity. -

Tree Ferns: Monophyletic Groups and Their Relationships As Revealed by Four Protein-Coding Plastid Loci

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 39 (2006) 830–845 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Tree ferns: Monophyletic groups and their relationships as revealed by four protein-coding plastid loci Petra Korall a,b,¤, Kathleen M. Pryer a, Jordan S. Metzgar a, Harald Schneider c, David S. Conant d a Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708, USA b Department of Phanerogamic Botany, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm, Sweden c Albrecht-von-Haller Institute für PXanzenwissenschaften, Georg-August-Universität, Göttingen, Germany d Natural Science Department, Lyndon State College, Lyndonville, VT 05851, USA Received 3 October 2005; revised 22 December 2005; accepted 2 January 2006 Available online 14 February 2006 Abstract Tree ferns are a well-established clade within leptosporangiate ferns. Most of the 600 species (in seven families and 13 genera) are arbo- rescent, but considerable morphological variability exists, spanning the giant scaly tree ferns (Cyatheaceae), the low, erect plants (Plagiogy- riaceae), and the diminutive endemics of the Guayana Highlands (Hymenophyllopsidaceae). In this study, we investigate phylogenetic relationships within tree ferns based on analyses of four protein-coding, plastid loci (atpA, atpB, rbcL, and rps4). Our results reveal four well-supported clades, with genera of Dicksoniaceae (sensu Kubitzki, 1990) interspersed among them: (A) (Loxomataceae, (Culcita, Pla- giogyriaceae)), (B) (Calochlaena, (Dicksonia, Lophosoriaceae)), (C) Cibotium, and (D) Cyatheaceae, with Hymenophyllopsidaceae nested within. How these four groups are related to one other, to Thyrsopteris, or to Metaxyaceae is weakly supported. Our results show that Dicksoniaceae and Cyatheaceae, as currently recognised, are not monophyletic and new circumscriptions for these families are needed. © 2006 Elsevier Inc. -

Annual Review of Pteridological Research - 2000

Annual Review of Pteridological Research - 2000 Annual Review of Pteridological Research - 2000 Literature Citations All Citations 1. Adhya, T. K., K. Bharati, S. R. Mohanty, B. Ramakrishnan, V. R. Rao, N. Sethunathan & R. Wassmann. 2000. Methane emission from rice fields at Cuttack, India. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 58: 95-105. [Azolla] 2. Ahlenslager, K. E. 2000. Conservation of rare plants on public lands. American Journal of Botany 87 Suppl. 6: 89. [Abstract] 3. Alam, M. S., N. Chopra, M. Ali & M. Niwa. 2000. Normethyl pentacyclic and lanostane-type triterpenes from Adiantum venustum. Phytochemistry (Oxford) 54: 215-220. 4. Allam, A. F. 2000. Evaluation of different means of control of snail intermediate host of Schistosoma mansoni. Journal of the Egyptian Society of Parasitology 30: 441-450. [Azolla pinnata] 5. Allison, A. & F. Kraus. 2000. A new species of frog of the genus Xenorhina (Anura: Microhylidae) from the north coast ranges of Papua New Guinea. Herpetologica 56: 285-294. [Asplenium] 6. Alonso-Amelot, M. E., M. P. Calcagno & M. Perez-Injosa. 2000. Growth and selective defensive potential in relation to altitude in neotropical Pteridium aquilinum var. caudatum. Pp. 43-47. In J. A. Taylor & R. T. Smith (Eds.). Bracken fern: toxicity, biology and control. International Bracken Group, Aberystwyth. 7. Alonso-Amelot, M. E., U. F. Castillo, M. Avendano, B. L. Smith & D. R. Lauren. 2000. Milk as a vehicle for the transfer of ptaquiloside, a bracken carcinogen. Pp. 86-90. In J. A. Taylor & R. T. Smith (Eds.). Bracken fern: toxicity, biology and control. International Bracken Group, Aberystwyth. [Pteridium aquilinum] 8. Alonso-Amelot, M. -

New Zealand Plants in Australian Gardens Stuart Read

New Zealand Plants in Australian Gardens Stuart Read Abstract: (11.6.2013): Raised in a large New Zealand garden full of native trees, plant lover Stuart Read was perhaps hard-wired to notice kiwi plants in Australian gardens. Over time he's pieced together a pattern of waves of fashion in their planting and popularity, reflecting scientific and horticultural expansionism, commercial and familial networks and connections across the Tasman. Stuart will examine a range of NZ plants found in old and younger Australian gardens, try to tease out some of the means by which they got here and why they remain popular. No cabbage, This constellation of asterisks Slaps and rustles Its tough tatters In the brisk breeze; Whispers of times past And ancient histories (Barbara Mitcalfe’s poem, ‘Ti Kouka’ (cabbage tree) catches well the distinctive skyline profile of this ubiquitous New Zealand export (in Simpson, 2000, 213) Introduction / overview New Zealand gardens have been introduced to and cultivated in Australian gardens from early in their ‘discovery’, trade and exchanges between the two colonies. Australian and other explorers, botanists, nurserymen, New Zealand settlers and others searched New Zealand’s coasts and bush, bringing plants into cultivation, export and commerce from early in the settlement’s colonization. New Zealand plants have had their ‘vogue’ periods, including as: A) - Economic plants (various timbers, kauri gum for shellacs and jewellery; flax for fibre, rope, cloth; greens for scurvy; poroporo for the contraceptive ‘the pill’); B) - Exotic ornamental imports into Australian gardens and beyond to English and European conservatories (and some warmer, southern) gardens and parks; C) - Depicted or carved as subjects of botanical and other artworks, commercial commodities. -

Spring 2007- 21 Fern Quarterly Spring 2007 President’S Message

THE HARDY FERN FOUNDATION P.O. Box 3797 Federal Way, WA 98063-3797 Web site: www.hardyfems.org The Hardy Fern Foundation was founded in 1989 to establish a comprehen¬ sive collection of the world’s hardy ferns for display, testing, evaluation, public education and introduction to the gardening and horticultural community. Many rare and unusual species, hybrids and varieties are being propagated from spores and tested in selected environments for their different degrees of hardiness and ornamental garden value. The primary fern display and test garden is located at, and in conjunction with, The Rhododendron Species Botanical Garden at the Weyerhaeuser Corpo¬ rate Headquarters, in Federal Way, Washington. Satellite fern gardens are at the Stephen Austin Arboretum, Nacogdoches, Texas, Birmingham Botanical Gardens, Birmingham, Alabama, California State University at Sacramento, Sacramento, California, Coastal Maine Botanical Garden, Boothbay, Maine, Dallas Arboretum, Dallas, Texas, Denver Botanic Gardens. Denver, Colorado, Georgeson Botanical Garden, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, Alaska, Harry P. Leu Garden, Orlando, Florida, Inniswood Metro Gardens, Columbus, Ohio, New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York, and Strybing Arboretum, San Francisco, California. The fern display gardens are at Bainbridge Island Library, Bainbridge Island, WA, Lakewold, Tacoma, Washington, Les Jardins de Metis, Quebec, Canada, Rotary Gardens, Janesville, Wl, University of Northern Colorado, Greeley, Colorado, and Whitehall Historic Home and Garden, Louisville, KY. Hardy Fern Foundation members participate in a spore exchange, receive a quarterly newsletter and have first access to ferns as they are ready for distribution. Cover Design by Willanna Bradner HARDY FERN FOUNDATION QUARTERLY THE HARDY FERN FOUNDATION QUARTERLY Volume 17 No.