The History of Kells Bay House & Gardens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kells Bay Nursery

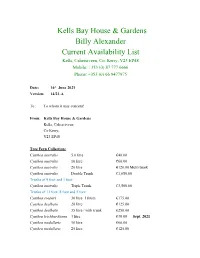

Kells Bay House & Gardens Billy Alexander Current Availability List Kells, Cahersiveen, Co. Kerry, V23 EP48 Mobile: +353 (0) 87 777 6666 Phone: +353 (0) 66 9477975 Date: 16th June 2021 Version: 14/21-A To : To whom it may concern! From: Kells Bay House & Gardens Kells, Caherciveen Co Kerry, V23 EP48 Tree Fern Collection: Cyathea australis 5.0 litre €40.00 Cyathea australis 10 litre €60.00 Cyathea australis 20 litre €120.00 Multi trunk Cyathea australis Double Trunk €1,650.00 Trunks of 9 foot and 1 foot Cyathea australis Triple Trunk €3,500.00 Trunks of 11 foot, 8 foot and 5 foot Cyathea cooperi 30 litre 180cm €175.00 Cyathea dealbata 20 litre €125.00 Cyathea dealbata 35 litre / with trunk €250.00 Cyathea leichhardtiana 3 litre €30.00 Sept. 2021 Cyathea medullaris 10 litre €60.00 Cyathea medullaris 25 litre €125.00 Cyathea medullaris 35 litre / 20-30cm trunk €225.00 Cyathea medullaris 45 litre / 50-60cm trunk €345.00 Cyathea tomentosisima 5 litre €50.00 Dicksonia antarctica 3.0 litre €12.50 Dicksonia antarctica 5.0 litre €22.00 These are home grown ferns naturalised in Kells Bay Gardens Dicksonia antarctica 35 litre €195.00 (very large ferns with emerging trunks and fantastic frond foliage) Dicksonia antarctica 20cm trunk €65.00 Dicksonia antarctica 30cm trunk €85.00 Dicksonia antarctica 60cm trunk €165.00 Dicksonia antarctica 90cm trunk €250.00 Dicksonia antarctica 120cm trunk €340.00 Dicksonia antarctica 150cm trunk €425.00 Dicksonia antarctica 180cm trunk €525.00 Dicksonia antarctica 210cm trunk €750.00 Dicksonia antarctica 240cm trunk €925.00 Dicksonia antarctica 300cm trunk €1,125.00 Dicksonia antarctica 360cm trunk €1,400.00 We have lots of multi trunks available, details available upon request. -

Irlands Langer Weg Vom Kolonialismus Zur Unabhängigkeit

Motiv: Dáil Bar © Ireland‘s Content Pool Irlands langer Weg vom Kolonialismus zur Unabhängigkeit Eine ganz ungewöhnliche Studienreise Donnerstag, 14.05.2020 - Donnerstag, 21.05.2020 veranstaltet vom Europäischen Bildungs- und Begegnungszentrum Irland in Zusammenarbeit mit der VHS Hagen und Arbeit und Leben DGB/VHS Regionalbüro Berg-Mark Diese Reise wird nicht nur erstmalige Irlandreisende erfreuen, sondern auch unsere „Wiederholungstäter*innen“ verblüffen. Denn diesmal wollen wir uns in eher selten be- suchte Regionen Irlands begeben und dabei immer wieder einen Blick auf die Abhängigkeit von England in der irischen Geschichte werfen: Zum einen in den Südosten der „Grünen Insel“, und zwar v.a. in die überraschend abwechslungsreichen Grafschaften Wexford und Waterford, die eng mit der Besetzung durch die Anglonormannen in der irischen Geschichte verbunden sind; und dann auch in den wunderbaren äußersten Südwesten Irlands, nämlich nach West Cork, in dem wir den Versuchen der Iren nachgehen, sich von der englischen Unterdrückung zu befreien. Die landschaftliche Vielfalt und die vielen langen Küstenstreifen der südirischen Atlantikküste, aber auch so manches kunsthistorische Kleinod und mancher Garten, die auch den englischen Herrschaftsanspruch dokumentieren, werden sie begeis- tern! Und selbstverständlich werden wir auch Gelegenheit zum Pub-Besuch und dem Erle- ben irischer traditioneller Musik haben! Das Programm (Änderungen vorbehalten) Tag 1: Donnerstag, 14.05.2020: Flug nach Irland - Powerscourt Garden - Wexford Flug von Düsseldorf nach Dublin. Wir fahren um Dublin herum in südliche Richtung und machen einen farbenfrohen Halt in der Nähe von Enniskerry: Der Powerscourt Garden and Estate, der ins 18. Jh. zurückreicht, ge- hört zu den bedeutendsten und schönsten in Großbritannien und Irland! Formale Gärten, stufenförmige Terrassen, ein wunderbarer See und japanischer Garten, uvm. -

Kenmare News [email protected] Page 17

FREE KENMARE NEWS June 2013 Vol 10, Issue 5 087 2513126 • 087 2330398 Love food? Tuosist ‘lifts Love the latch’ Let’s party in The Kenmare? ...See Breadcrumb! ...See page 24 ...See page 17 pages and much, 20/ 21 much more! SeanadóirSenator Marcus Mark O’Dalaigh Daly SherryAUCTIONEERS FitzGerald & VALUERS T: 064-6641213 Daly Lackeen, 39 Year Campaign Blackwater 4 Bed Detached House for New Kenmare Panoramic Sea Views Hospital Successful 6 miles to Kenmare Town Mob: 086 803 2612 Clinics held in the Michael Atlantic Bar and all Asking Price surrounding €395,000 Healy-Rae parishes on a Sean Daly & Co Ltd T.D. regular basis. Insurance Brokers EVERY SUNDAY NIGHT IN KILGARVAN: Before you Renew your Insurance (Household, Motor or Commercial) HEALY-RAE’S MACE - 9PM – 10PM Talk to us FIRST - 064-6641213 HEALY-RAE’S BAR - 10PM – 11PM We Give Excellent Quotations. Tel: 064 66 32467 • Fax : 064 6685904 • Mobile: 087 2461678 Sean Daly & Co Ltd, 34 Henry St, Kenmare T: 064-6641213 E-mail: [email protected] • Johnny Healy-Rae MCC 087 2354793 TAXI KENMARE Cllr. Patrick Denis & Mags Griffin O’ Connor-Scarteen M: 087 2904325 087 614 7222 €8 Million for Kenmare Hospital by FG led Government See Page 16 Kenmare Furniture Bedding & Suites 064 6641404 OPENINGKenmare Business HOURS: Park, Killarney MON.-SAT.: Road, Kenmare. 10am-6pm Email: [email protected] Web: www.kenmarefurniture.com Come in and see the fabulous new ranges now in stock Page 2 Phone 087 2513126 • 087 2330398 Kenmare News The July edition of The Kenmare News will be Kenmare sisters, published on Friday July 26th and closing date for Cora and Sabrina O’Leary are submissions is Friday July 19th. -

Waipa District Development and Subdivision Manual

Table of Contents Waipa District Development and Subdivision Manual Waipa District Development and Subdivision Manual 2015 Page 1 How to Use the Manual How to Use the Manual Please note that Waipa District Council has no controls over the way your electronic device prints the electronic version of the Manual and cannot guarantee that it will be consistent with the published version of the Manual. Version Control Version Date Updated By Section / Page # and Details 1.0 November 2012 Administrator Document approved by Council. 2.0 August 2013 Development Engineer Whole document updated to reflect OFI forms received. 2.1 September 2013 Development Engineer Whole document updated 2.2 August 2014 Development Engineer Whole document updated to reflect feedback from internal review. 2.3 December 2014 Development Engineer Whole document approved by Asset Managers 2.4 January 2015 Administrator Whole document renumbered and formatted. 2.5 May 2015 Administrator Document approved by Council. Page 2 Waipa District Development and Subdivision Manual 2015 Table of Contents Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ 3 Part 1: Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 5 Part 2: General Information ............................................................................................................ 7 Volume 1: Subdivision and Land Use Processes -

TAXON:Dicksonia Squarrosa (G. Forst.) Sw. SCORE

TAXON: Dicksonia squarrosa (G. SCORE: 18.0 RATING: High Risk Forst.) Sw. Taxon: Dicksonia squarrosa (G. Forst.) Sw. Family: Dicksoniaceae Common Name(s): harsh tree fern Synonym(s): Trichomanes squarrosum G. Forst. rough tree fern wheki Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 11 Sep 2019 WRA Score: 18.0 Designation: H(HPWRA) Rating: High Risk Keywords: Tree Fern, Invades Pastures, Dense Stands, Suckering, Wind-Dispersed Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 n Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 ? outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 n 402 Allelopathic 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable to grazing animals y=1, n=-1 n 405 Toxic to animals y=1, n=0 n 406 Host for recognized pests and pathogens 407 Causes allergies or is otherwise toxic to humans 408 Creates a fire hazard in natural ecosystems y=1, n=0 y 409 Is a shade tolerant plant at some stage of its life cycle y=1, n=0 y Creation Date: 11 Sep 2019 (Dicksonia squarrosa (G. -

Irsko Beara Peninsula Letní Pobyty 2016

www.jekacs.cz, e-mail: [email protected] PRŮVODCE PRO VEDOUCÍHO SKUPINY DOPLNĚK IRSKO BEARA PENINSULA LETNÍ POBYTY 2016 JEKA–CS, K Lomu 889, 252 29 Dobřichovice, Praha západ, tel. 257 712 049, 602 398 263, 602 215 376, fax: 257 710 307, 257 710 388 V této části Průvodce naleznete podrobné informace a popisy městeček a obcí, přírodních zajímavostí, tras, památek megalitických, keltských i křesťanských, i poznámky k mytologii. Na své denní výlety si tak můžete vzít s sebou vždy jen několik stránek týkajících se vašich cílů. POLOOSTROV BEARA PENINSULA ..................................................................................................... 3 OBCE A MĚSTA NA POLOOSTROVĚ BEARA ...................................................................................... 11 OSTROVY BANTRY BAY A TRAJEKTY ............................................................................................... 28 BEARA WAY - PAMÁTKY A ZAJÍMAVOSTI NA TRASE ....................................................................... 42 PŘÍRODNÍ REZERVACE GLENGARRIFF ............................................................................................ 55 TURISTICKÉ CÍLE V MÍSTECH UBYTOVÁNÍ ...................................................................................... 58 DALŠÍ ZAJÍMAVÉ CÍLE NA TRASE DO/Z UBYTOVÁNÍ....................................................................... 61 WHISKEY A PIVO .................................................................................................................................. 63 DUBLIN……………. -

Taxi Kenmare

Page 01:Layout 1 14/10/13 4:53 PM Page 1 If it’s happening in Kenmare, it’s in the Kenmarenews FREE October 2013 www.kenmarenews.biz Vol 10, Issue 9 kenmareDon’t miss All newsBusy month Humpty happening for Dumpty at Internazionale Duathlon Kenmare FC ...See GAA ...See page page 40 ...See 33 page 32 SeanadóirSenator Marcus Mark O’Dalaigh Daly SherryAUCTIONEERS FitzGerald & VALUERS T: 064-6641213 Daly Coomathloukane, Caherdaniel Kenmare • 3 Bed Detached House • Set on c.3.95 acres votes to retain • Sea Views • In Need of Renovation •All Other Lots Sold atAuction Mob: 086 803 2612 the Seanad • 3.5 Miles to Caherdaniel Village Clinics held in the Michael Atlantic Bar and all € surrounding Offers In Excess of: 150,000 Healy-Rae parishes on a T.D. regular basis. Sean Daly & Co Ltd EVERY SUNDAY NIGHT IN KILGARVAN: Insurance Brokers HEALY-RAE’S MACE - 9PM – 10PM Before you Renew your Insurance (Household, Motor or Commercial) HEALY-RAE’S BAR - 10PM – 11PM Talk to us FIRST - 064-6641213 We Give Excellent Quotations. Tel: 064 66 32467 • Fax : 064 6685904 • Mobile: 087 2461678 Sean Daly & Co Ltd, 34 Henry St, Kenmare T: 064-6641213 E-mail: [email protected] • Johnny Healy-Rae MCC 087 2354793 Cllr. Patrick TAXI KENMARE Denis & Mags Griffin O’ Connor-ScarteenM: 087 2904325 Sneem & Kilgarvan 087 614 7222 Wastewater Systems See Notes on Page 16 Page 02:Layout 1 14/10/13 4:55 PM Page 1 2 | Kenmare News Mary Falvey was the winner of the baking Denis O'Neill competition at and his daughter Blackwater Sports, Rebecca at and she is pictured Edel O'Neill here with judges and Stephen Steve and Louise O'Brien's Austin. -

Hugust, 1940 THREEPE CE

VOL. xv. No. Jl. Hugust, 1940 THREEPE CE GLENDALOCH. THE VALLEY OF THE TWO LAKES. At Glendaloch, in the heart of Mountainous Wicklow, Saint Kev.in in the sixth century founded a monastery which subsequently became a renowned European centre of learning. Its ruins, now eloquent of former glory, lie in a glen romantic with the beauty of its dark wild scenery. IRISH TRAVEL August, 1940 CONNEMARA HEART OF THE GAELTACHT. Excellent \\'hite and Brown Trout fishing leased by Hotel-free to visitors-within easy walking distance. Best ea Fishing. Boating. Beautiful Strands. 60,000 acres shooting. Best centre for seeing Connemara and Aran BANK OF IRELAND I lands. A.A., LT.A., R.LA.C. appointments. H. and C. running water. Electric Light. Garages. Full particulars apply:- FACILITIES FOR TRAVELLERS MONGAN'S AT Head Omce: COLLEGE GREEN, DUBLIN : HOTEL:~ BELFAST .. CORK .. DERRY AID 100 TOWRS THROUOHOOT IRELARD; Carna :: Connemara IRELAND EVERT DJ:80RIPTION 01' FOREIGN J:XOHANG. I BU8INJ:8S TRAN8AO'1'J:D ON ARRIVAL OF LINERS I! Telegrams: :.\Iongan's, Carna. 'Phone, Carna 3 BY DAT OR NIGHT AT OOBH (QUEEN8TOWN) I CONNEMARA'S CHIEF FISHING RESORT AND GALWAY DOOXS. 'DUBLIN The , GreShaIll Hotel Suites with Private Bathrooms. Ballroom. Central Heating. Telephone and Hot and Cold Running .. I VISITORS TO Water in every Bedroom. .. invariably make their way to Clerys-which has Restaurant, gamed widespread fame as one of the most pro Grill Room, gressive and beautiful Department Stores in Europe. § Tea Lounge and Clerys present a vast Hall of modern merchandise Modern Snack of the very best quality at keenest prices. -

Save Kilmakilloge Group

Save Kilmakilloge Group Aquaculture Licences Appeals Board (ALAB), Kilminchy Court, Portlaoise, Co. Laois, 23 Oct 2019 To whom it may concern Re: Appeal request for Aquaculture Licence Granted to Kush Seafarms Ltd Site Ref No: T06/513A We, a group of local mussel farmers, inshore fishermen, tourist businesses, residents and regular visitors would like to request an appeal and oral hearing to the granting of a licence to the above. Our principle concerns are - Site is over traditional fishing grounds. - Impeding; of main navigation route into the harbour. - Overstocking of the harbour with mussels threating livelihood of existing mussel farmers. Secondary concerns are - Visual and other environmental impacts - Tourism impact These concerns are further elaborated in 3 categories as follows - Local inshore fishermen - Local existing mussel fanners - Other interested parties (Tourism, residents and regular visitors) We would to grateful for your serious consideration of this appeal. Yours faithfully INS John O'Sullivan (for the fishermen) Raymo ss (for Mussel farmers) Janet Hawker (Other) ATTACHMENTS 1) ALAB Appeal Application Form 2) Bank Draft 3) Appeal for Oral Hearing Form 4) Letter of appeal from Inshore Fishermen 5) Letter of appeal from Local Mussel Farmers 6) Appeal from Other Interested parties a) Letter of Appeal b) Email request for support c) List of signatories d) Supplementary Emails from local tourist businesses e) Wild Atlantic Way viewpoint maps and photos Appeal request: Site Ref No: T06/513A Page 1 of 1 NOTICE OF APPEAL -

A Synthesis of Geophysical and Biological Assessment to Determine Restoration Priorities

How can geomorphology inform ecological restoration? A synthesis of geophysical and biological assessment to determine restoration priorities A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Master of Science Degree in Physical Geography By Leicester Cooper School of Geography, Environment and Earth Sciences Victoria University Wellington 2012 _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Acknowledgements Many thanks and much appreciation go to my supervisors Dr Bethanna Jackson and Dr Paul Blaschke, whose sage advice improved this study. Thanks for stepping into the breach; I hope you didn’t regret it. Thanks to the Scholarships Office for the Victoria Master’s (by thesis) Scholarship Support award which has made the progression of the study much less stressful. Thanks go to the various agencies that have provided assistance including; Stefan Ziajia from Kapiti Coast District Council, Nick Page from Greater Wellington Regional Council, Eric Stone from Department of Conservation, Kapiti office. Appreciation and thanks go to Will van Cruchten, for stoically putting up with my frequent calls requesting access to Whareroa Farm. Also, many thanks to Prof. Shirley Pledger for advice and guidance in relation to the statistical methods and analysis without whom I might still be working on the study. Any and all mistakes contained within I claim sole ownership of. Thanks to the generous technicians in the Geography department, Andrew Rae and Hamish McKoy and fellow students, including William Ries, for assistance with procurement of aerial images and Katrin Sattler for advice in image processing. To Dr Murray Williams, without whose sudden burst at one undergraduate lecture I would not have strayed down the path of ecological restoration. -

Official Organ of the Irish Tourist Association

Official Organ of the Irish Tourist Association Vol. XIII.-No. 6. MARCH. 1938. Threepence. An Aran Jarvey, wearing, like all his fellow-islandmen, the Aran homespun costume-the U bawneen," or white woollen coat, the grey-blue rough woollen pants, and the handsome home-made indigo jersey, which the Aran housewives so rou In' Qt IRISH TRAVEL February, 1938 IRELAND for Happy Holidays BEAUTY - SPORT - HISTORY - ROMANCE You may travel by any ot the RESORTS SERVED BY following steamship routes: GREAT SOUTHERN HOLYHEAD - KINGSTO\VN RAILWAYS ACHILL . ARKLOW .AVOCA . ATHLO E LIVERPOOL - DUBLIN BALLI A. BRAY . BANTRY . BALLYBUNION BALLYVAUGHAN . BLARNEY . BUNDORAN FISHGUARD ROSSLARE CASHEL . CARAGH LAKE . CASTLECON ELL CASTLEGREGORY CLO" AKILTY CORK FISHGUARD -WATERFORD COB H COURTMACSHERRY CLIFDEN CONNEMARA . CLONMEL . DUN LAOGHAIRE FISHGUARD - CORK DALKEY . DUNMORE . DUNGARVAN . DINGLE By whichever route you travel you are sure of FOYNES GLENBEIGH (for Rossbeigh Strand) GREYSTO ES GLENDALOUGH a fast, comfortable journey by modern turbine GLENGARRIFF GAL WAY KILLINEY steamers. Luxurious express trains connect the KEN 1\1 ARE KILLARNEY KILLALOE Ports of both HOLYHEAD and FISHGUARD KILKEE LIMERICK LAHI TCH with all the important centres of population and LISDOO VAR A MALLARANNY MULLINGAR· MILTOWN MALBAY industry and the Holiday Resorts of Great PARK ASILLA' ROSSLARE . SCHULL . SLIGO Britain. The trains of the Great Southern TRAMORE V ALE I CIA WESTPORT Railways Company connect with the steamers. WICKLOW • WOODENBRIDGE • YOUGHAL HOTELS OF DISTINCTION Under Great Southern Railwavs' Managetnent These Hotels are replete with every comfort, and are beautifully situated 'midst the gorgeous scenery of the South and West. The Tariffs are moderate. Combined Rail and Hotel Tickets issued. -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 689 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feedback goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. Anthony Sheehy, Mike at the Hunt Museum, OUR READERS Steve Whitfield, Stevie Winder, Ann in Galway, Many thanks to the travellers who used the anonymous farmer who pointed the way to the last edition and wrote to us with help- Knockgraffon Motte and all the truly delightful ful hints, useful advice and interesting people I met on the road who brought sunshine anecdotes: to the wettest of Irish days. Thanks also, as A Andrzej Januszewski, Annelise Bak C Chris always, to Daisy, Tim and Emma. Keegan, Colin Saunderson, Courtney Shucker D Denis O’Sullivan J Jack Clancy, Jacob Catherine Le Nevez Harris, Jane Barrett, Joe O’Brien, John Devitt, Sláinte first and foremost to Julian, and to Joyce Taylor, Juliette Tirard-Collet K Karen all of the locals, fellow travellers and tourism Boss, Katrin Riegelnegg L Laura Teece, Lavin professionals en route for insights, information Graviss, Luc Tétreault M Marguerite Harber, and great craic.