Pteridologist 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DENNSTAEDTIACEAE 1. MONACHOSORUM Kunze, Bot. Zeitung (Berlin) 6: 119. 1848

This PDF version does not have an ISBN or ISSN and is not therefore effectively published (Melbourne Code, Art. 29.1). The printed version, however, was effectively published on 6 June 2013. Yan, Y. H., X. P. Qi, W. B. Liao, F. W. Xing, M. Y. Ding, F. G. Wang, X. C. Zhang, Z. H. Wu, S. Serizawa, J. Prado, A. M. Funston, M. G. Gilbert & H. P. Nooteboom. 2013. Dennstaedtiaceae. Pp. 147–168 in Z. Y. Wu, P. H. Raven & D. Y. Hong, eds., Flora of China, Vol. 2–3 (Pteridophytes). Beijing: Science Press; St. Louis: Missouri Botanical Garden Press. DENNSTAEDTIACEAE 碗蕨科 wan jue ke Yan Yuehong (严岳鸿)1, Qi Xinping (齐新萍)2, Liao Wenbo (廖文波)3, Xing Fuwu (邢福武)4, Ding Mingyan (丁明艳)3, Wang Faguo (王发国)4, Zhang Xianchun (张宪春)5, Wu Zhaohong (吴兆洪 Wu Shiew-hung)4; Shunshuke Serizawa6, Jefferson Prado7, A. Michele Funston8, Michael G. Gilbert9, Hans P. Nooteboom10 Plants terrestrial, sometimes climbing. Rhizome usually long creeping, solenostelic, siphonostelic, or polystelic, usually covered with multicellular hairs, less often with few-celled, cylindrical, glandular hairs or multicellular bristles, scales absent. Fronds medium-sized to large, sometimes indeterminate, monomorphic; stipes not articulate to rhizome, usually hairy, rarely glabrous; lamina 1–4-pinnately compound, thinly herbaceous to leathery, hairy or glabrous, without scales; rachis grooved adaxially, some- times with buds (Monachosorum); pinnae opposite or alternate; veins usually free, pinnate or forked, not reaching margin, reticulate without included veinlets in Histiopteris. Sori marginal or intramarginal, linear or orbicular, terminal on a veinlet or on a vascular commissure joining apices of veins; indusia linear or bowl-shaped, sometimes double with outer false indusium formed from thin reflexed lamina margin and inconspicuous inner true indusium; paraphyses present or not. -

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

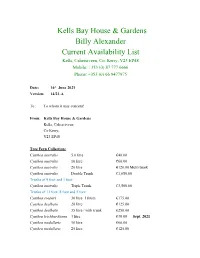

Kells Bay Nursery

Kells Bay House & Gardens Billy Alexander Current Availability List Kells, Cahersiveen, Co. Kerry, V23 EP48 Mobile: +353 (0) 87 777 6666 Phone: +353 (0) 66 9477975 Date: 16th June 2021 Version: 14/21-A To : To whom it may concern! From: Kells Bay House & Gardens Kells, Caherciveen Co Kerry, V23 EP48 Tree Fern Collection: Cyathea australis 5.0 litre €40.00 Cyathea australis 10 litre €60.00 Cyathea australis 20 litre €120.00 Multi trunk Cyathea australis Double Trunk €1,650.00 Trunks of 9 foot and 1 foot Cyathea australis Triple Trunk €3,500.00 Trunks of 11 foot, 8 foot and 5 foot Cyathea cooperi 30 litre 180cm €175.00 Cyathea dealbata 20 litre €125.00 Cyathea dealbata 35 litre / with trunk €250.00 Cyathea leichhardtiana 3 litre €30.00 Sept. 2021 Cyathea medullaris 10 litre €60.00 Cyathea medullaris 25 litre €125.00 Cyathea medullaris 35 litre / 20-30cm trunk €225.00 Cyathea medullaris 45 litre / 50-60cm trunk €345.00 Cyathea tomentosisima 5 litre €50.00 Dicksonia antarctica 3.0 litre €12.50 Dicksonia antarctica 5.0 litre €22.00 These are home grown ferns naturalised in Kells Bay Gardens Dicksonia antarctica 35 litre €195.00 (very large ferns with emerging trunks and fantastic frond foliage) Dicksonia antarctica 20cm trunk €65.00 Dicksonia antarctica 30cm trunk €85.00 Dicksonia antarctica 60cm trunk €165.00 Dicksonia antarctica 90cm trunk €250.00 Dicksonia antarctica 120cm trunk €340.00 Dicksonia antarctica 150cm trunk €425.00 Dicksonia antarctica 180cm trunk €525.00 Dicksonia antarctica 210cm trunk €750.00 Dicksonia antarctica 240cm trunk €925.00 Dicksonia antarctica 300cm trunk €1,125.00 Dicksonia antarctica 360cm trunk €1,400.00 We have lots of multi trunks available, details available upon request. -

LCSH Section L

L (The sound) Formal languages La Boderie family (Not Subd Geog) [P235.5] Machine theory UF Boderie family BT Consonants L1 algebras La Bonte Creek (Wyo.) Phonetics UF Algebras, L1 UF LaBonte Creek (Wyo.) L.17 (Transport plane) BT Harmonic analysis BT Rivers—Wyoming USE Scylla (Transport plane) Locally compact groups La Bonte Station (Wyo.) L-29 (Training plane) L2TP (Computer network protocol) UF Camp Marshall (Wyo.) USE Delfin (Training plane) [TK5105.572] Labonte Station (Wyo.) L-98 (Whale) UF Layer 2 Tunneling Protocol (Computer network BT Pony express stations—Wyoming USE Luna (Whale) protocol) Stagecoach stations—Wyoming L. A. Franco (Fictitious character) BT Computer network protocols La Borde Site (France) USE Franco, L. A. (Fictitious character) L98 (Whale) USE Borde Site (France) L.A.K. Reservoir (Wyo.) USE Luna (Whale) La Bourdonnaye family (Not Subd Geog) USE LAK Reservoir (Wyo.) LA 1 (La.) La Braña Region (Spain) L.A. Noire (Game) USE Louisiana Highway 1 (La.) USE Braña Region (Spain) UF Los Angeles Noire (Game) La-5 (Fighter plane) La Branche, Bayou (La.) BT Video games USE Lavochkin La-5 (Fighter plane) UF Bayou La Branche (La.) L.C.C. (Life cycle costing) La-7 (Fighter plane) Bayou Labranche (La.) USE Life cycle costing USE Lavochkin La-7 (Fighter plane) Labranche, Bayou (La.) L.C. Smith shotgun (Not Subd Geog) La Albarrada, Battle of, Chile, 1631 BT Bayous—Louisiana UF Smith shotgun USE Albarrada, Battle of, Chile, 1631 La Brea Avenue (Los Angeles, Calif.) BT Shotguns La Albufereta de Alicante Site (Spain) This heading is not valid for use as a geographic L Class (Destroyers : 1939-1948) (Not Subd Geog) USE Albufereta de Alicante Site (Spain) subdivision. -

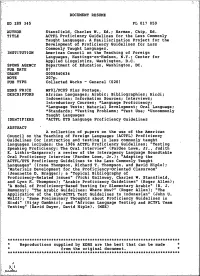

Harman, Chip, Ed. ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines For

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 289 345 FL 017 059 AUTHOR Stansfield, Charles W., Ed.; Harman, Chip, Ed. TITLE ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines for the Less Commonly Taught Languages. A Familiarization Project for the Development of Proficiency Guidelines for Less Commonly Taught Languages. INSTITUTION American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages, Hastings-on-Hudson, N.Y.; Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 87 "GRANT G008540634 NOTE 207p. PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS African Languages; Arabic; Bibliographies; Hindi; Indonesian; Information Sources; Interviews; Introductory Courses; *Language Proficiency; *Language Tests; Material Development; Oral Language; *Standards; *Testing Problems; *Test Use; *Uncommonly Taught Languages IDEnTIFIERS *ACTFL ETS Language Proficiency Guidelines ABSTRACT A collection of papers on the use of the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) Proficiency Guidelines for instruction and testing in less commonly taught language& includes: the 1986 ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines; "Testing Speaking Proficiency: The Oral Interview" (Pardee Lowe, Jr., Judith E. Liskin-Gasparro); a review of the Interagency Language Roundtable Oral Proficiency Interview (Pardee Lowe, Jr.); "Adapting the ACTFL/ETS Proficiency Guidelines to the Less Commonly Taught languages" (Irene Thompson, Richard T. Thompson, and David Hiple); "Materials Development for the Proficiency-Oriented Classroom" (Jeannette D. Bragger); a "Topical Bibliography of Proficiency-Related Issues" (Vicki Galloway, Charles W. Stansfield, and Lynn E. Thompson); "Arabic Proficiency Guidelines" (Roger Allen); "A Model of Proficiency-Based Testing for Elementary Arabic" (R. J. Rumunny); "The Arabic Guidelines: Where Now?" (Roger Allen); "The Application of the ILR-ACTFL Test Guidelines to Indonesian" (John U. -

Waipa District Development and Subdivision Manual

Table of Contents Waipa District Development and Subdivision Manual Waipa District Development and Subdivision Manual 2015 Page 1 How to Use the Manual How to Use the Manual Please note that Waipa District Council has no controls over the way your electronic device prints the electronic version of the Manual and cannot guarantee that it will be consistent with the published version of the Manual. Version Control Version Date Updated By Section / Page # and Details 1.0 November 2012 Administrator Document approved by Council. 2.0 August 2013 Development Engineer Whole document updated to reflect OFI forms received. 2.1 September 2013 Development Engineer Whole document updated 2.2 August 2014 Development Engineer Whole document updated to reflect feedback from internal review. 2.3 December 2014 Development Engineer Whole document approved by Asset Managers 2.4 January 2015 Administrator Whole document renumbered and formatted. 2.5 May 2015 Administrator Document approved by Council. Page 2 Waipa District Development and Subdivision Manual 2015 Table of Contents Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ 3 Part 1: Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 5 Part 2: General Information ............................................................................................................ 7 Volume 1: Subdivision and Land Use Processes -

Ophioglossum Nudicaule L.F

Available online at www.ijpab.com ISSN: 2320 – 7051 Int. J. Pure App. Biosci. 2 (2): 163-173 (2014) Research Article INTERNATIONAL JO URNAL OF PURE & APPLIED BIOSCIENCE Recognition of plant associations useful for conservation of Ophioglossum nudicaule L.f. and Ophioglossum vulgatum L. in the eastern lateritic part of India Sumit Manna 1 and Anirban Roy 2* 1West Bengal Biodiversity Board, Department of Environment, Government of West Bengal. Paribesh Bhawan, 10 A, LA Block, Sector- III, Saltlake City, Kolkata – 700098 West Bengal. India 2West Bengal Biodiversity Board, Department of Environment, Government of West Bengal. Paribesh Bhawan, 10 A, LA Block, Sector- III, Saltlake City, Kolkata – 700098 West Bengal. India *Corresponding Author E-mail: [email protected] ______________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT For the past few decades, populations of different species of Ophioglossum (Ophioglossaceae) including Ophioglossum nudicaule and Ophioglossum vulgatum have become more restricted in geographic range due to alteration of their actual or potential habitat conditions and therefore are designated as rare species of India. To find out the potential habitats of Ophioglossum for protection of their ancient gene pool, it is important to identify their plant associates as well as the nature of those associations. Structural parameters of the community such as density, abundance, frequency, relative abundance, relative frequency and importance value index of these two species of Ophioglossum and their co-existing plants were measured based on a quadrat study of three tropical deciduous forests of the lateritic part of West Bengal, India. This study reveals that there is a strong negative correlation in the association of O. nudicaule and O. -

This Is Para

UNCORRECTED TRANSCRIPT OF ORAL EVIDENCE To be published as HC 757-ii HOUSE OF COMMONS ORAL EVIDENCE TAK EN BEFORE THE HOME AFFAIRS COMMITTEE POLICE AND CRIME COMMISSIONERS: PROGRESS TO DATE TUESDAY 7 JANUARY 2014 KATY BOURNE and ANTHONY STANSFELD CHIEF CONSTABLE MARTIN RICHARDS and CHIEF CONSTABLE SARA THO RNTON LORD STEVENS and PROFESSOR IAN LOADER Evidence heard in Public Questions 128 - 360 USE OF THE TRANSCRIPT 1. This is an uncorrected transcript of evidence taken in public and reported to the House. The transcript has been placed on the internet on the authority of the Committee, and copies have been made available by the Vote Office for the use of Members and others. 2. Any public use of, or reference to, the contents should make clear that neither witnesses nor Members have had the opportunity to correct the record. The transcript is not yet an approved formal record of these proceedings. 3. Members who receive this for the purpose of correcting questions addressed by the m to witnesses are asked to send corrections to the Committee Assistant. 4. Prospective witnesses may receive this in preparation for any written or oral evidence they may in due course give to the Committee. 1 Oral Evidence Taken before the Home Affairs Committee on Tuesday 7 January 2014 Members present: Keith Vaz (Chair) Mr James Clappison Michael Ellis Paul Flynn Lorraine Fullbrook Dr Julian Huppert Yasmin Qureshi Mark Reckless Mr David Winnick Examination of Witnesses Witnesses: Katy Bourne, Police and Crime Commissioner for Sussex, and Anthony Stansfeld, Police and Crime Commissioner for Thames Valley, gave evidence. -

TAXON:Dicksonia Squarrosa (G. Forst.) Sw. SCORE

TAXON: Dicksonia squarrosa (G. SCORE: 18.0 RATING: High Risk Forst.) Sw. Taxon: Dicksonia squarrosa (G. Forst.) Sw. Family: Dicksoniaceae Common Name(s): harsh tree fern Synonym(s): Trichomanes squarrosum G. Forst. rough tree fern wheki Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 11 Sep 2019 WRA Score: 18.0 Designation: H(HPWRA) Rating: High Risk Keywords: Tree Fern, Invades Pastures, Dense Stands, Suckering, Wind-Dispersed Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 n Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 ? outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 n 402 Allelopathic 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable to grazing animals y=1, n=-1 n 405 Toxic to animals y=1, n=0 n 406 Host for recognized pests and pathogens 407 Causes allergies or is otherwise toxic to humans 408 Creates a fire hazard in natural ecosystems y=1, n=0 y 409 Is a shade tolerant plant at some stage of its life cycle y=1, n=0 y Creation Date: 11 Sep 2019 (Dicksonia squarrosa (G. -

Plant Charts for Native to the West Booklet

26 Pohutukawa • Oi exposed coastal ecosystem KEY ♥ Nurse plant ■ Main component ✤ rare ✖ toxic to toddlers coastal sites For restoration, in this habitat: ••• plant liberally •• plant generally • plant sparingly Recommended planting sites Back Boggy Escarp- Sharp Steep Valley Broad Gentle Alluvial Dunes Area ment Ridge Slope Bottom Ridge Slope Flat/Tce Medium trees Beilschmiedia tarairi taraire ✤ ■ •• Corynocarpus laevigatus karaka ✖■ •••• Kunzea ericoides kanuka ♥■ •• ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• Metrosideros excelsa pohutukawa ♥■ ••••• • •• •• Small trees, large shrubs Coprosma lucida shining karamu ♥ ■ •• ••• ••• •• •• Coprosma macrocarpa coastal karamu ♥ ■ •• •• •• •••• Coprosma robusta karamu ♥ ■ •••••• Cordyline australis ti kouka, cabbage tree ♥ ■ • •• •• • •• •••• Dodonaea viscosa akeake ■ •••• Entelea arborescens whau ♥ ■ ••••• Geniostoma rupestre hangehange ♥■ •• • •• •• •• •• •• Leptospermum scoparium manuka ♥■ •• •• • ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• Leucopogon fasciculatus mingimingi • •• ••• ••• • •• •• • Macropiper excelsum kawakawa ♥■ •••• •••• ••• Melicope ternata wharangi ■ •••••• Melicytus ramiflorus mahoe • ••• •• • •• ••• Myoporum laetum ngaio ✖ ■ •••••• Olearia furfuracea akepiro • ••• ••• •• •• Pittosporum crassifolium karo ■ •• •••• ••• Pittosporum ellipticum •• •• Pseudopanax lessonii houpara ■ ecosystem one •••••• Rhopalostylis sapida nikau ■ • •• • •• Sophora fulvida west coast kowhai ✖■ •• •• Shrubs and flax-like plants Coprosma crassifolia stiff-stemmed coprosma ♥■ •• ••••• Coprosma repens taupata ♥ ■ •• •••• •• -

Species Relationships and Farina Evolution in the Cheilanthoid Fern

Systematic Botany (2011), 36(3): pp. 554–564 © Copyright 2011 by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists DOI 10.1600/036364411X583547 Species Relationships and Farina Evolution in the Cheilanthoid Fern Genus Argyrochosma (Pteridaceae) Erin M. Sigel , 1 , 3 Michael D. Windham , 1 Layne Huiet , 1 George Yatskievych , 2 and Kathleen M. Pryer 1 1 Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708 U. S. A. 2 Missouri Botanical Garden, P.O. Box 299, St. Louis, Missouri 63166 U. S. A. 3 Author for correspondence ( [email protected] ) Communicating Editor: Lynn Bohs Abstract— Convergent evolution driven by adaptation to arid habitats has made it difficult to identify monophyletic taxa in the cheilanthoid ferns. Dependence on distinctive, but potentially homoplastic characters, to define major clades has resulted in a taxonomic conundrum: all of the largest cheilanthoid genera have been shown to be polyphyletic. Here we reconstruct the first comprehensive phylogeny of the strictly New World cheilanthoid genus Argyrochosma . We use our reconstruction to examine the evolution of farina (powdery leaf deposits), which has played a prominent role in the circumscription of cheilanthoid genera. Our data indicate that Argyrochosma comprises two major monophyletic groups: one exclusively non-farinose and the other primarily farinose. Within the latter group, there has been at least one evolutionary reversal (loss) of farina and the development of major chemical variants that characterize specific clades. Our phylogenetic hypothesis, in combination with spore data and chromosome counts, also provides a critical context for addressing the prevalence of polyploidy and apomixis within the genus. Evidence from these datasets provides testable hypotheses regarding reticulate evolution and suggests the presence of several previ- ously undetected taxa of Argyrochosma. -

Four Western Cheilanthoid Ferns in Oklahoma

Oklahoma Native Plant Record 65 Volume 10, December 2010 FOUR WESTERN CHEILANTHOID FERNS IN OKLAHOMA Bruce A. Smith McLoud High School McLoud, Oklahoma 74851 Keywords: arid, distribution, habitat, key ABSTRACT The diversity of ferns in some of the more arid climates of western Oklahoma is surprising. This article examines four Oklahoma cheilanthoid ferns: Astrolepis integerrima, Cheilanthes wootonii, Notholaena standleyi, and Pellaea wrightiana. With the exceptions of A. integerrima and P. wrightiana which occur in Alabama and North Carolina respectively, all four species reach their eastern limits of distribution in Oklahoma. Included in this article are common names, synonyms, brief descriptions, distinguishing characteristics, U.S. and Oklahoma distribution, habitat information, state abundance, and a dichotomous key to selected cheilanthoids. The Oklahoma Natural Heritage Inventory has determined that all but one (N. standleyi) are species of concern in the state. INTRODUCTION of eastern Oklahoma, while most members of the Pteridaceae occur in Almost half of the ferns in the family western Oklahoma (Taylor & Taylor Pteridaceae are xeric adapted ferns. In 1991). Oklahoma six genera and sixteen species Statewide, the most common species in the family are known to occur. They in the Pteridaceae is Pellaea atropurpurea live on dry or moist rocks and can be (Figure 4), which can be found found in rock crevices, at the bases of throughout the body of the state and boulders, or on rocky ledges. Common Cimarron County in the panhandle. The associated species include lichens, mosses, rarest are Cheilanthes horridula and liverworts, and spike mosses. Two Cheilanthes lindheimeri. Cheilanthes horridula physical characteristics that unite the and Cheilanthes lindheimeri have only been family are the marginal sori (Figure 1) and seen in one county each, Murray and the lack of a true indusium.