This Is Para

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sussex CJB Notes 070318

SU RREY AND SUSSEX CRIMINAL JUSTICE PARTNERSHIPS Criminal Justice System: working together for the public Sussex Criminal Justice Board Meeting Minutes 09:30 – 10:20hrs, Wednesday 7th March 2018 Sackville House, Lewes 1. Welcome, Apologies and Declarations – Katy Bourne Katy Bourne (Chairman) Sussex Police and Crime Commissioner KB Lisa Ramsarran CPS LR Mark Streater Office of the Sussex Police & Crime Commissioner MSt Dave Manning HM Courts & Tribunals Service DMa Simon Nelson Sussex Police SN Suki Binning Seetec Group- Kent, Surrey & Sussex CRC (dial in ) SB Nick Pascoe HM Prison and Probation Service NP Andrea Saunders HM Prison and Probation Service AS Emily King West Sussex County Council EK Peter Castleton Brighton and Hove City Council PC Jo Player Brighton and Hove City Council JP Rob McCauley Legal Aid Agency RM Maralyn Smith Victim Support MS Christiane Jourdain NHS England CJ Peter Gates NHS England PG Sam Sanderson Women in CJS – Project Manager SS Rebecca Hills Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust RH Tania Riedel Sussex YOT’s TR Bruce Tippen SSCJP Business Manager BT Lindsey Parris SSCJP LP Observing: David Munro Surrey Police and Crime Commissioner DM Pippa Clark Surrey County Council PCl Apologies received from: Jaswant Narwal Chief Crown Prosecutor – CPS JN Samantha Allen Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust SA Debbie Cropanese HM Courts & Tribunals Service – Head of Crime DC Wendy Tattersall Public Health England WT Susanne Jarman Citizens Advice – Witness Service SJ Justine Armstrong-Smith East Sussex County Council JAS Rodney Warren Warrens Solicitors RW Ian Whiteside HMP Bronzefield IW Vicky Robinson HMP Bronzefield VR Laurence Taylor Sussex Police LT Jane Macdougall WMC Legal LLP JM Stephen Fradley HMP Ford SF Anne Elgeti NHS England AE KB welcomed members to the SCJB meeting and reported it would be Peter Castleton’s last SCJB meeting owing to his retirement. -

Sussex Criminal Justice Board Meeting Minutes

SUSUSURREYSU RREY AND SUSSEX Agenda item c2 CRIMINAL JUSTICE PARTNERSHIPS Criminal Justice System: working together for the public Criminal Justice System: working together for the public Sussex Criminal Justice Board Meeting Minutes 09:30 – 10:15hrs, Monday 25th March 2019 Sackville House, Lewes BN7 2FZ 1. Welcome, Apologies and Declarations – Katy Bourne Katy Bourne (Chairman) Sussex Police and Crime Commissioner KB Frank Ferguson Chief Crown Prosecutor - South East (Vice Chairman) FF Mark Streater Office of the Sussex Police & Crime Commissioner MSt Claire Mullarkey HM Courts & Tribunals Service (Head of Crime) CM Dave Manning HM Courts & Tribunals Service DMa Sam Newbould KSS Community Rehabilitation Company SNe Jason Taylor Sussex Police JT Sam Sanderson Sussex Police (dial-in) SS Mark Burden HM Prison and Probation Service MB Rob McCauley Legal Aid Agency RM Stephen Fradley HMP Ford SF Tania Riedel Sussex YOS TR Emily King West Sussex County Council EK Jo Player Brighton and Hove City Council JP Maralyn Smith Victim Support MS Bruce Tippen SSCJP Business Manager BT Lindsey Parris SSCJP LP Observing: David Munro Surrey Police and Crime Commissioner DM Alison Bolton Office of the Surrey Police and Crime Commissioner AB Violet Hancock High Sheriff (East Sussex) VH Davina Irwin-Clark High Sheriff (West Sussex) DIC Kevin Smyth Under Sheriff KS Apologies received from: Sarah Coccia HM Prison and Probation Service SC Andrea Saunders HM Prison and Probation Service AS Wendy Tattersall Public Health England WT Simon Nelson Sussex Police -

LCSH Section L

L (The sound) Formal languages La Boderie family (Not Subd Geog) [P235.5] Machine theory UF Boderie family BT Consonants L1 algebras La Bonte Creek (Wyo.) Phonetics UF Algebras, L1 UF LaBonte Creek (Wyo.) L.17 (Transport plane) BT Harmonic analysis BT Rivers—Wyoming USE Scylla (Transport plane) Locally compact groups La Bonte Station (Wyo.) L-29 (Training plane) L2TP (Computer network protocol) UF Camp Marshall (Wyo.) USE Delfin (Training plane) [TK5105.572] Labonte Station (Wyo.) L-98 (Whale) UF Layer 2 Tunneling Protocol (Computer network BT Pony express stations—Wyoming USE Luna (Whale) protocol) Stagecoach stations—Wyoming L. A. Franco (Fictitious character) BT Computer network protocols La Borde Site (France) USE Franco, L. A. (Fictitious character) L98 (Whale) USE Borde Site (France) L.A.K. Reservoir (Wyo.) USE Luna (Whale) La Bourdonnaye family (Not Subd Geog) USE LAK Reservoir (Wyo.) LA 1 (La.) La Braña Region (Spain) L.A. Noire (Game) USE Louisiana Highway 1 (La.) USE Braña Region (Spain) UF Los Angeles Noire (Game) La-5 (Fighter plane) La Branche, Bayou (La.) BT Video games USE Lavochkin La-5 (Fighter plane) UF Bayou La Branche (La.) L.C.C. (Life cycle costing) La-7 (Fighter plane) Bayou Labranche (La.) USE Life cycle costing USE Lavochkin La-7 (Fighter plane) Labranche, Bayou (La.) L.C. Smith shotgun (Not Subd Geog) La Albarrada, Battle of, Chile, 1631 BT Bayous—Louisiana UF Smith shotgun USE Albarrada, Battle of, Chile, 1631 La Brea Avenue (Los Angeles, Calif.) BT Shotguns La Albufereta de Alicante Site (Spain) This heading is not valid for use as a geographic L Class (Destroyers : 1939-1948) (Not Subd Geog) USE Albufereta de Alicante Site (Spain) subdivision. -

Harman, Chip, Ed. ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines For

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 289 345 FL 017 059 AUTHOR Stansfield, Charles W., Ed.; Harman, Chip, Ed. TITLE ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines for the Less Commonly Taught Languages. A Familiarization Project for the Development of Proficiency Guidelines for Less Commonly Taught Languages. INSTITUTION American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages, Hastings-on-Hudson, N.Y.; Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 87 "GRANT G008540634 NOTE 207p. PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS African Languages; Arabic; Bibliographies; Hindi; Indonesian; Information Sources; Interviews; Introductory Courses; *Language Proficiency; *Language Tests; Material Development; Oral Language; *Standards; *Testing Problems; *Test Use; *Uncommonly Taught Languages IDEnTIFIERS *ACTFL ETS Language Proficiency Guidelines ABSTRACT A collection of papers on the use of the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) Proficiency Guidelines for instruction and testing in less commonly taught language& includes: the 1986 ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines; "Testing Speaking Proficiency: The Oral Interview" (Pardee Lowe, Jr., Judith E. Liskin-Gasparro); a review of the Interagency Language Roundtable Oral Proficiency Interview (Pardee Lowe, Jr.); "Adapting the ACTFL/ETS Proficiency Guidelines to the Less Commonly Taught languages" (Irene Thompson, Richard T. Thompson, and David Hiple); "Materials Development for the Proficiency-Oriented Classroom" (Jeannette D. Bragger); a "Topical Bibliography of Proficiency-Related Issues" (Vicki Galloway, Charles W. Stansfield, and Lynn E. Thompson); "Arabic Proficiency Guidelines" (Roger Allen); "A Model of Proficiency-Based Testing for Elementary Arabic" (R. J. Rumunny); "The Arabic Guidelines: Where Now?" (Roger Allen); "The Application of the ILR-ACTFL Test Guidelines to Indonesian" (John U. -

Rmit-V-Stansfield-Judgment---Final-24102018-Pdf.Pdf

IN THE HIGH COURT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE [2018] SGHC 232 Suit No 65 of 2013 Between Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology … Plaintiff And (1) Stansfield College Pte Ltd (2) TSG Investments Pte Ltd … Defendants JUDGMENT [Civil Procedure] — [Pleadings] [Contract] — [Discharge] — [Breach] [Contract] — [Misrepresentation] — [Statements of intention] [Contract] — [Waiver] [Restitution] — [Mistake] — [Mistake of law] [Restitution] — [Unjust enrichment] — [Failure of consideration] TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION............................................................................................1 THE PARTIES .................................................................................................2 THE FACTS .....................................................................................................3 THE 2006 AGREEMENTS..................................................................................4 THE 2009 AGREEMENTS..................................................................................5 THE AMENDING AGREEMENTS........................................................................8 TERMINATION OF THE 2009 AGREEMENTS ......................................................9 THE PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM ........................................................................13 THE FIRST DEFENDANT’S COUNTERCLAIM ....................................18 ISSUES ............................................................................................................19 ISSUE 1: THE PLAINTIFF’S ALLEGED REPUDIATORY -

Pteridologist 2007

PTERIDOLOGIST 2007 CONTENTS Volume 4 Part 6, 2007 EDITORIAL James Merryweather Instructions to authors NEWS & COMMENT Dr Trevor Walker Chris Page 166 A Chilli Fern? Graham Ackers 168 The Botanical Research Fund 168 Miscellany 169 IDENTIFICATION Male Ferns 2007 James Merryweather 172 TREE-FERN NEWSLETTER No. 13 Hyper-Enthusiastic Rooting of a Dicksonia Andrew Leonard 178 Most Northerly, Outdoor Tree Ferns Alastair C. Wardlaw 178 Dicksonia x lathamii A.R. Busby 179 Tree Ferns at Kells House Garden Martin Rickard 181 FOCUS ON FERNERIES Renovated Palace for Dicksoniaceae Alastair C. Wardlaw 184 The Oldest Fernery? Martin Rickard 185 Benmore Fernery James Merryweather 186 FEATURES Recording Ferns part 3 Chris Page 188 Fern Sticks Yvonne Golding 190 The Stansfield Memorial Medal A.R. Busby 191 Fern Collections in Manchester Museum Barbara Porter 193 What’s Dutch about Dutch Rush? Wim de Winter 195 The Fine Ferns of Flora Græca Graham Ackers 203 CONSERVATION A Case for Ex Situ Conservation? Alastair C. Wardlaw 197 IN THE GARDEN The ‘Acutilobum’ Saga Robert Sykes 199 BOOK REVIEWS Encyclopedia of Garden Ferns by Sue Olsen Graham Ackers 170 Fern Books Before 1900 by Hall & Rickard Clive Jermy 172 Britsh Ferns DVD by James Merryweather Graham Ackers 187 COVER PICTURE: The ancestor common to all British male ferns, the mountain male fern Dryopteris oreades, growing on a ledge high on the south wall of Bealach na Ba (the pass of the cattle) Unless stated otherwise, between Kishorn and Applecross in photographs were supplied the Scottish Highlands - page 172. by the authors of the articles PHOTO: JAMES MERRYWEATHER in which they appear. -

Updated 31.10.12)

Police and Crime Commissioners: Who’s running? (updated 31.10.12) This table lists those candidates who are confirmed as standing in the first elections for Police and Crime Commissioners on 15 November 2012. For more information on these candidates, click on their name. To view to view a historical list of all candidates, including unsuccessful candidates and those who withdrew, scroll down to the second table. Force Conservatives Labour Liberal Democrats UKIP Other parties Independent Avon and Somerset Ken Maddock John Savage Pete Levy Sue Mountstevens Bedfordshire Jas Parmar Oliver Martins Linda Jack Kevin Carroll (British Freedom/EDL) Mezanur Rashid Cambridgeshire Graham Bright Ed Murphy Rupert Moss- Paul Bullen Stephen Goldspink (English Ansar Ali Eccardt Democrats) Farooq Mohammed Cheshire John Dwyer John Stockton Ainsley Arnold Louise Bours Sarah Flannery Cleveland Ken Lupton Barry Coppinger Joe Michna (Green Party) Sultan Alam Cumbria Richard Rhodes Patrick Leonard Pru Jupe Mary Robinson Derbyshire Simon Spencer Alan Charles David Gale Rod Hutton Devon and Cornwall Tony Hogg Nicky Williams Brian Blake Bob Smith Graham Calderwood Brian Greenslade Ivan Jordan Tam MacPherson William Morris John Smith Dorset Nick King Rachel Rogers Andy Canning Martyn Underhill Durham Nick Varley Ron Hogg Mike Costello Kingsley Smith Dyfed-Powys Christopher Salmon Christine Gwyther Essex Nicholas Alston Val Morris-Cook Andrew Smith Robin Tilbrook (English Democrats) Linda Belgrove Mick Thwaites Gloucestershire Victoria Atkins Rupi Dhanda Alistair -

Police and Crime Commissioners: Here to Stay

House of Commons Home Affairs Committee Police and Crime Commissioners: here to stay Seventh Report of Session 2015–16 HC 844 House of Commons Home Affairs Committee Police and Crime Commissioners: here to stay Seventh Report of Session 2015–16 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 22 March 2016 HC 844 Published on 25 March 2016 by authority of the House of Commons Home Affairs Committee The Home Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Home Office and its associated public bodies. Current membership Rt Hon Keith Vaz MP (Labour, Leicester East) (Chair) Victoria Atkins MP (Conservative, Louth and Horncastle) James Berry MP (Conservative, Kingston and Surbiton) Mr David Burrowes MP (Conservative, Enfield, Southgate) Nusrat Ghani MP (Conservative, Wealden) Mr Ranil Jayawardena MP (Conservative, North East Hampshire) Tim Loughton MP (Conservative, East Worthing and Shoreham) Stuart C. McDonald MP (Scottish National Party, Cumbernauld, Kilsyth and Kirkintilloch East) Naz Shah MP (Labour, Bradford West) Mr Chuka Umunna MP (Labour, Streatham) Mr David Winnick MP (Labour, Walsall North) The following were also members of the Committee during the Parliament. Keir Starmer MP (Labour, Holborn and St Pancras) Anna Turley MP (Labour, Redcar) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication Committee reports are published on the Committee’s website at www.parliament.uk/homeaffairscom and in print by Order of the House. -

Dame Sara Thornton DBE QPM Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner 5Th Floor, Globe House 89 Eccleston Square London, SW1V 1PN

Dame Sara Thornton DBE QPM Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner 5th Floor, Globe House 89 Eccleston Square London, SW1V 1PN Tel: +44 (0) 20 3513 0477 Email: [email protected] 13 October 2020 Katy Bourne OBE Sussex Police and Crime Commissioner Office of the Sussex Police & Crime Commissioner Sackville House Brooks Close Lewes East Sussex BN7 2FZ Dear Katy, As Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner, I am writing in connection with my statutory responsibility to encourage good practice in the prevention, detection, investigation and prosecution of modern slavery offences and the identification of victims. My office comprises of a small team with policy leads aligned to each of the priorities set out within my Strategic Plan 2019-2021: improving victim care and support; supporting law enforcement and prosecutions; focusing on prevention; getting value out of research and innovation; as well as a policy lead for international activity. In September 2020 I published my Annual Report outlining my work so far to achieve the objectives within my Strategic Plan 2019-2021. I was pleased to see the announcement1 in late 2019 regarding the significant government investment to provide Police and Crime Commissioners in eighteen areas across England and Wales with additional funding for two years to tackle violent crime. I understand that this funding is being used to bring together multi-agency partners including the police, local authorities, the health sector, community groups and third sector organisations to establish or build upon existing Violence Reduction Units (VRUs) to better understand what is driving violent crime and deliver co-ordinated initiatives that focus on prevention and early intervention. -

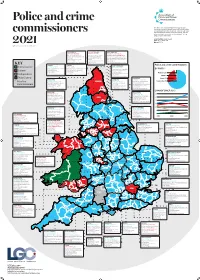

PCC Map 2021

Police and crime The APCC is the national body which supports police and crime commissioners and other local policing bodies across England and Wales to provide national leadership commissioners and drive strategic change across the policing, criminal justice and wider community safety landscape, to help keep our communities safe. [email protected] www.apccs.police.uk 2021 @assocPCCs © Local Government Chronicle 2021 NORTHUMBRIA SOUTH YORKSHIRE WEST YORKSHIRE KIM MCGUINNESS (LAB) ALAN BILLINGS (LAB) MAYOR TRACY BRABIN (LAB) First elected 2019 by-election. First elected 2014 by-election. Ms Brabin has nominated Alison Lowe Former cabinet member, Newcastle Former Anglican priest and (Lab) as deputy mayor for policing. Former City Council. deputy leader, Sheffield City councillor, Leeds City Council and chair of www.northumbria-pcc.gov.uk Council. West Yorkshire Police and Crime Panel. 0191 221 9800 www.southyorkshire-pcc.gov.uk 0113 348 1740 [email protected] 0114 296 4150 [email protected] KEY [email protected] CUMBRIA DURHAM Police and crime commissioners NORTH YORKSHIRE PETER MCCALL (CON) JOY ALLEN (LAB) Conservative PHILIP ALLOTT (CON)* First elected 2016. Former colonel, Former Durham CC cabinet member and Former councillor, Harrogate BC; BY PARTY Royal Logistic Corps. former police and crime panel chair. former managing director of Labour www.cumbria-pcc.gov.uk www.durham-pcc.gov.uk marketing company. 01768 217734 01913 752001 Plaid Cymru 1 www.northyorkshire-pfcc.gov.uk Independent [email protected] [email protected] 01423 569562 Vacant 1 [email protected] Plaid Cymru HUMBERSIDE Labour 11 LANCASHIRE CLEVELAND JONATHAN EVISON (CON) * Also fi re ANDREW SNOWDEN (CON) NORTHUMBRIA STEVE TURNER (CON) Councillor at North Lincolnshire Conservative 29 Former lead member for highways Former councillor, Redcar & Council and former chair, Humberside Police and Crime Panel. -

Funding Special Constables Membership of the Police Federation

15 June 2020 Dear Police and Crime Commissioner, Funding Special Constables membership of the Police Federation The Home Office has confirmed a change in legislation as part of the Police Powers and Protections Bill in the autumn will allow Special Constables to join the Police Federation. This is very welcome as it will allow Specials the same level of representation enjoyed by paid police officers. Discussions are currently taking place between the Home Office, Police Federation, Association of Special Constabulary Officers, APCC and NPCC as to the mechanics of the representation and to ensure that special constables are able to take up membership as soon as the legislative change comes into effect. One of the issues under discussion is funding for the membership subscriptions of those special constables that wish to take up Police Federation membership. Although there is agreement that the special constables themselves, as volunteers, should not have to pay the subscription there is no clear consensus at this stage as to who should pay the bill. John Apter, National Chair of the Police Federation, addressed the APCC General Meeting in January 2020 and asked us to consider whether PCCs could fund specials’ membership of the Federation and this was well received by those members present. And we are aware that many of you will have had conversations on this matter with your local branch chairs. It is currently reckoned there are some 11,690 special constables across England and Wales and subscription rates set at £21.58 the cost of Police Federation membership for the entire Special Constabulary would be in the region of £3m a year. -

(Vrus) in FOCUS a Multi-Agency and Public Health Approach to Support Young People and Divert Them Away from Serious Violent Crime

PCCs MAKING A DIFFERENCE VIOLENCE REDUCTION UNITS (VRUs) IN FOCUS A multi-agency and public health approach to support young people and divert them away from serious violent crime VIOLENCE REDUCTION UNITS IN FOCUS.indd 1 08/09/2020 14:23 king a Di a ffe M r e s n C c e C P VRUs IN FOCUS PCCs MAKING A DIFFERENCE VIOLENCE REDUCTION UNITS ( VRUs) IN FOCUS Foreword from Mark Burns-Williamson OBE, APCC Serious Violence Lead and West Yorkshire’s PCC I’m very pleased to introduce this latest ‘In Focus’ edition. PCCs have been working closely with the National Police Chiefs’ Council, the Home Office, public health and many other key partners to help reduce the threat of Serious Violent Crime throughout England & Wales. Serious violence can blight communities and lead to devastating consequences and although the impact is more often felt in our large cities, the problem also reaches into our towns and rural areas. Any approach needs to be evidence-based and consistent, investing in effective preventative measures over a sustained period of time. When the Government’s Serious Violence Strategy was launched in 2018, the APCC and I were clear that early intervention and prevention with a public health, whole-system approach was key to success over the longer term. By taking such an approach we can collectively continue our vital work to support young people in particular and divert them away from serious violent crime. Establishing and embedding a sustainable approach to tackling violent crime and its underlying causes can only happen by working closely with our partners and engaging with the communities most affected.