Police and Crime Commissioners: Here to Stay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sussex CJB Notes 070318

SU RREY AND SUSSEX CRIMINAL JUSTICE PARTNERSHIPS Criminal Justice System: working together for the public Sussex Criminal Justice Board Meeting Minutes 09:30 – 10:20hrs, Wednesday 7th March 2018 Sackville House, Lewes 1. Welcome, Apologies and Declarations – Katy Bourne Katy Bourne (Chairman) Sussex Police and Crime Commissioner KB Lisa Ramsarran CPS LR Mark Streater Office of the Sussex Police & Crime Commissioner MSt Dave Manning HM Courts & Tribunals Service DMa Simon Nelson Sussex Police SN Suki Binning Seetec Group- Kent, Surrey & Sussex CRC (dial in ) SB Nick Pascoe HM Prison and Probation Service NP Andrea Saunders HM Prison and Probation Service AS Emily King West Sussex County Council EK Peter Castleton Brighton and Hove City Council PC Jo Player Brighton and Hove City Council JP Rob McCauley Legal Aid Agency RM Maralyn Smith Victim Support MS Christiane Jourdain NHS England CJ Peter Gates NHS England PG Sam Sanderson Women in CJS – Project Manager SS Rebecca Hills Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust RH Tania Riedel Sussex YOT’s TR Bruce Tippen SSCJP Business Manager BT Lindsey Parris SSCJP LP Observing: David Munro Surrey Police and Crime Commissioner DM Pippa Clark Surrey County Council PCl Apologies received from: Jaswant Narwal Chief Crown Prosecutor – CPS JN Samantha Allen Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust SA Debbie Cropanese HM Courts & Tribunals Service – Head of Crime DC Wendy Tattersall Public Health England WT Susanne Jarman Citizens Advice – Witness Service SJ Justine Armstrong-Smith East Sussex County Council JAS Rodney Warren Warrens Solicitors RW Ian Whiteside HMP Bronzefield IW Vicky Robinson HMP Bronzefield VR Laurence Taylor Sussex Police LT Jane Macdougall WMC Legal LLP JM Stephen Fradley HMP Ford SF Anne Elgeti NHS England AE KB welcomed members to the SCJB meeting and reported it would be Peter Castleton’s last SCJB meeting owing to his retirement. -

Sussex Criminal Justice Board Meeting Minutes

SUSUSURREYSU RREY AND SUSSEX Agenda item c2 CRIMINAL JUSTICE PARTNERSHIPS Criminal Justice System: working together for the public Criminal Justice System: working together for the public Sussex Criminal Justice Board Meeting Minutes 09:30 – 10:15hrs, Monday 25th March 2019 Sackville House, Lewes BN7 2FZ 1. Welcome, Apologies and Declarations – Katy Bourne Katy Bourne (Chairman) Sussex Police and Crime Commissioner KB Frank Ferguson Chief Crown Prosecutor - South East (Vice Chairman) FF Mark Streater Office of the Sussex Police & Crime Commissioner MSt Claire Mullarkey HM Courts & Tribunals Service (Head of Crime) CM Dave Manning HM Courts & Tribunals Service DMa Sam Newbould KSS Community Rehabilitation Company SNe Jason Taylor Sussex Police JT Sam Sanderson Sussex Police (dial-in) SS Mark Burden HM Prison and Probation Service MB Rob McCauley Legal Aid Agency RM Stephen Fradley HMP Ford SF Tania Riedel Sussex YOS TR Emily King West Sussex County Council EK Jo Player Brighton and Hove City Council JP Maralyn Smith Victim Support MS Bruce Tippen SSCJP Business Manager BT Lindsey Parris SSCJP LP Observing: David Munro Surrey Police and Crime Commissioner DM Alison Bolton Office of the Surrey Police and Crime Commissioner AB Violet Hancock High Sheriff (East Sussex) VH Davina Irwin-Clark High Sheriff (West Sussex) DIC Kevin Smyth Under Sheriff KS Apologies received from: Sarah Coccia HM Prison and Probation Service SC Andrea Saunders HM Prison and Probation Service AS Wendy Tattersall Public Health England WT Simon Nelson Sussex Police -

This Is Para

UNCORRECTED TRANSCRIPT OF ORAL EVIDENCE To be published as HC 757-ii HOUSE OF COMMONS ORAL EVIDENCE TAK EN BEFORE THE HOME AFFAIRS COMMITTEE POLICE AND CRIME COMMISSIONERS: PROGRESS TO DATE TUESDAY 7 JANUARY 2014 KATY BOURNE and ANTHONY STANSFELD CHIEF CONSTABLE MARTIN RICHARDS and CHIEF CONSTABLE SARA THO RNTON LORD STEVENS and PROFESSOR IAN LOADER Evidence heard in Public Questions 128 - 360 USE OF THE TRANSCRIPT 1. This is an uncorrected transcript of evidence taken in public and reported to the House. The transcript has been placed on the internet on the authority of the Committee, and copies have been made available by the Vote Office for the use of Members and others. 2. Any public use of, or reference to, the contents should make clear that neither witnesses nor Members have had the opportunity to correct the record. The transcript is not yet an approved formal record of these proceedings. 3. Members who receive this for the purpose of correcting questions addressed by the m to witnesses are asked to send corrections to the Committee Assistant. 4. Prospective witnesses may receive this in preparation for any written or oral evidence they may in due course give to the Committee. 1 Oral Evidence Taken before the Home Affairs Committee on Tuesday 7 January 2014 Members present: Keith Vaz (Chair) Mr James Clappison Michael Ellis Paul Flynn Lorraine Fullbrook Dr Julian Huppert Yasmin Qureshi Mark Reckless Mr David Winnick Examination of Witnesses Witnesses: Katy Bourne, Police and Crime Commissioner for Sussex, and Anthony Stansfeld, Police and Crime Commissioner for Thames Valley, gave evidence. -

Updated 31.10.12)

Police and Crime Commissioners: Who’s running? (updated 31.10.12) This table lists those candidates who are confirmed as standing in the first elections for Police and Crime Commissioners on 15 November 2012. For more information on these candidates, click on their name. To view to view a historical list of all candidates, including unsuccessful candidates and those who withdrew, scroll down to the second table. Force Conservatives Labour Liberal Democrats UKIP Other parties Independent Avon and Somerset Ken Maddock John Savage Pete Levy Sue Mountstevens Bedfordshire Jas Parmar Oliver Martins Linda Jack Kevin Carroll (British Freedom/EDL) Mezanur Rashid Cambridgeshire Graham Bright Ed Murphy Rupert Moss- Paul Bullen Stephen Goldspink (English Ansar Ali Eccardt Democrats) Farooq Mohammed Cheshire John Dwyer John Stockton Ainsley Arnold Louise Bours Sarah Flannery Cleveland Ken Lupton Barry Coppinger Joe Michna (Green Party) Sultan Alam Cumbria Richard Rhodes Patrick Leonard Pru Jupe Mary Robinson Derbyshire Simon Spencer Alan Charles David Gale Rod Hutton Devon and Cornwall Tony Hogg Nicky Williams Brian Blake Bob Smith Graham Calderwood Brian Greenslade Ivan Jordan Tam MacPherson William Morris John Smith Dorset Nick King Rachel Rogers Andy Canning Martyn Underhill Durham Nick Varley Ron Hogg Mike Costello Kingsley Smith Dyfed-Powys Christopher Salmon Christine Gwyther Essex Nicholas Alston Val Morris-Cook Andrew Smith Robin Tilbrook (English Democrats) Linda Belgrove Mick Thwaites Gloucestershire Victoria Atkins Rupi Dhanda Alistair -

Dame Sara Thornton DBE QPM Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner 5Th Floor, Globe House 89 Eccleston Square London, SW1V 1PN

Dame Sara Thornton DBE QPM Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner 5th Floor, Globe House 89 Eccleston Square London, SW1V 1PN Tel: +44 (0) 20 3513 0477 Email: [email protected] 13 October 2020 Katy Bourne OBE Sussex Police and Crime Commissioner Office of the Sussex Police & Crime Commissioner Sackville House Brooks Close Lewes East Sussex BN7 2FZ Dear Katy, As Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner, I am writing in connection with my statutory responsibility to encourage good practice in the prevention, detection, investigation and prosecution of modern slavery offences and the identification of victims. My office comprises of a small team with policy leads aligned to each of the priorities set out within my Strategic Plan 2019-2021: improving victim care and support; supporting law enforcement and prosecutions; focusing on prevention; getting value out of research and innovation; as well as a policy lead for international activity. In September 2020 I published my Annual Report outlining my work so far to achieve the objectives within my Strategic Plan 2019-2021. I was pleased to see the announcement1 in late 2019 regarding the significant government investment to provide Police and Crime Commissioners in eighteen areas across England and Wales with additional funding for two years to tackle violent crime. I understand that this funding is being used to bring together multi-agency partners including the police, local authorities, the health sector, community groups and third sector organisations to establish or build upon existing Violence Reduction Units (VRUs) to better understand what is driving violent crime and deliver co-ordinated initiatives that focus on prevention and early intervention. -

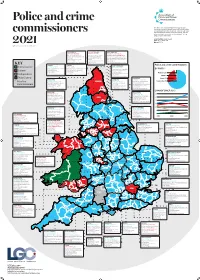

PCC Map 2021

Police and crime The APCC is the national body which supports police and crime commissioners and other local policing bodies across England and Wales to provide national leadership commissioners and drive strategic change across the policing, criminal justice and wider community safety landscape, to help keep our communities safe. [email protected] www.apccs.police.uk 2021 @assocPCCs © Local Government Chronicle 2021 NORTHUMBRIA SOUTH YORKSHIRE WEST YORKSHIRE KIM MCGUINNESS (LAB) ALAN BILLINGS (LAB) MAYOR TRACY BRABIN (LAB) First elected 2019 by-election. First elected 2014 by-election. Ms Brabin has nominated Alison Lowe Former cabinet member, Newcastle Former Anglican priest and (Lab) as deputy mayor for policing. Former City Council. deputy leader, Sheffield City councillor, Leeds City Council and chair of www.northumbria-pcc.gov.uk Council. West Yorkshire Police and Crime Panel. 0191 221 9800 www.southyorkshire-pcc.gov.uk 0113 348 1740 [email protected] 0114 296 4150 [email protected] KEY [email protected] CUMBRIA DURHAM Police and crime commissioners NORTH YORKSHIRE PETER MCCALL (CON) JOY ALLEN (LAB) Conservative PHILIP ALLOTT (CON)* First elected 2016. Former colonel, Former Durham CC cabinet member and Former councillor, Harrogate BC; BY PARTY Royal Logistic Corps. former police and crime panel chair. former managing director of Labour www.cumbria-pcc.gov.uk www.durham-pcc.gov.uk marketing company. 01768 217734 01913 752001 Plaid Cymru 1 www.northyorkshire-pfcc.gov.uk Independent [email protected] [email protected] 01423 569562 Vacant 1 [email protected] Plaid Cymru HUMBERSIDE Labour 11 LANCASHIRE CLEVELAND JONATHAN EVISON (CON) * Also fi re ANDREW SNOWDEN (CON) NORTHUMBRIA STEVE TURNER (CON) Councillor at North Lincolnshire Conservative 29 Former lead member for highways Former councillor, Redcar & Council and former chair, Humberside Police and Crime Panel. -

Funding Special Constables Membership of the Police Federation

15 June 2020 Dear Police and Crime Commissioner, Funding Special Constables membership of the Police Federation The Home Office has confirmed a change in legislation as part of the Police Powers and Protections Bill in the autumn will allow Special Constables to join the Police Federation. This is very welcome as it will allow Specials the same level of representation enjoyed by paid police officers. Discussions are currently taking place between the Home Office, Police Federation, Association of Special Constabulary Officers, APCC and NPCC as to the mechanics of the representation and to ensure that special constables are able to take up membership as soon as the legislative change comes into effect. One of the issues under discussion is funding for the membership subscriptions of those special constables that wish to take up Police Federation membership. Although there is agreement that the special constables themselves, as volunteers, should not have to pay the subscription there is no clear consensus at this stage as to who should pay the bill. John Apter, National Chair of the Police Federation, addressed the APCC General Meeting in January 2020 and asked us to consider whether PCCs could fund specials’ membership of the Federation and this was well received by those members present. And we are aware that many of you will have had conversations on this matter with your local branch chairs. It is currently reckoned there are some 11,690 special constables across England and Wales and subscription rates set at £21.58 the cost of Police Federation membership for the entire Special Constabulary would be in the region of £3m a year. -

(Vrus) in FOCUS a Multi-Agency and Public Health Approach to Support Young People and Divert Them Away from Serious Violent Crime

PCCs MAKING A DIFFERENCE VIOLENCE REDUCTION UNITS (VRUs) IN FOCUS A multi-agency and public health approach to support young people and divert them away from serious violent crime VIOLENCE REDUCTION UNITS IN FOCUS.indd 1 08/09/2020 14:23 king a Di a ffe M r e s n C c e C P VRUs IN FOCUS PCCs MAKING A DIFFERENCE VIOLENCE REDUCTION UNITS ( VRUs) IN FOCUS Foreword from Mark Burns-Williamson OBE, APCC Serious Violence Lead and West Yorkshire’s PCC I’m very pleased to introduce this latest ‘In Focus’ edition. PCCs have been working closely with the National Police Chiefs’ Council, the Home Office, public health and many other key partners to help reduce the threat of Serious Violent Crime throughout England & Wales. Serious violence can blight communities and lead to devastating consequences and although the impact is more often felt in our large cities, the problem also reaches into our towns and rural areas. Any approach needs to be evidence-based and consistent, investing in effective preventative measures over a sustained period of time. When the Government’s Serious Violence Strategy was launched in 2018, the APCC and I were clear that early intervention and prevention with a public health, whole-system approach was key to success over the longer term. By taking such an approach we can collectively continue our vital work to support young people in particular and divert them away from serious violent crime. Establishing and embedding a sustainable approach to tackling violent crime and its underlying causes can only happen by working closely with our partners and engaging with the communities most affected. -

Police and Crime Commissioners: Register of Interests

House of Commons Home Affairs Committee Police and Crime Commissioners: Register of Interests First Report of Session 2013–14 HC 69 House of Commons Home Affairs Committee Police and Crime Commissioners First Report of Session 2013–14 Volume I: Report, together with formal minutes Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 16 May 2013 HC 69 Published on 23 May 2013 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 Home Affairs Committee The Home Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Home Office and its associated public bodies. Current membership Rt Hon Keith Vaz MP (Labour, Leicester East) (Chair) Nicola Blackwood MP (Conservative, Oxford West and Abingdon) James Clappison MP (Conservative, Hertsmere) Michael Ellis MP (Conservative, Northampton North) Lorraine Fullbrook MP (Conservative, South Ribble) Dr Julian Huppert MP (Liberal Democrat, Cambridge) Steve McCabe MP (Labour, Birmingham Selly Oak) Bridget Phillipson MP (Labour, Houghton and Sunderland South) Mark Reckless MP (Conservative, Rochester and Strood) Chris Ruane MP (Labour, Vale of Clwyd) Mr David Winnick MP (Labour, Walsall North) The following Members were also members of the Committee during the parliament. Rt Hon Alun Michael MP (Labour & Co-operative, Cardiff South and Penarth) Karl Turner MP (Labour, Kingston upon Hull East) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. -

Police and Crime Commissioner Elections 2021 - PCC Candidate Contacts

Police and Crime Commissioner Elections 2021 - PCC Candidate Contacts Police service PCC status Name email twitter Party Avon & Somerset Retiring PCC Sue Mountstevens [email protected] Independent Avon & Somerset PCC candidate Mark Shelford [email protected] ShelfordMark Conservative Avon & Somerset PCC candidate John Smith [email protected] johndpcc Independent Avon & Somerset PCC candidate Kerry Barker kerrybarker22 Labour Bedfordshire Retiring PCC Kathryn Holloway [email protected] Conservative Bedfordshire PCC candidate Festus Akinbusoye [email protected] Fest4BedsPCC Conservative Bedfordshire PCC candidate Jas Parmar [email protected] Liberal Democrats Bedfordshire PCC candidate David Michael DavidMical Labour Cambridgeshire Acting PCC Ray Bisby [email protected] Conservative Cambridgeshire PCC candidate Darryl Preston [email protected] DarrylPreston_ Conservative Cambridgeshire PCC candidate Rupert Moss-Eccardt [email protected] rm113 Liberal Democrats Cambridgeshire PCC candidate Nicky Massey [email protected] @nmassey79 Labour Cheshire PCC David Keane [email protected] CheshirePCC Labour Cheshire PCC candidate John Dwyer [email protected] Conservative Cleveland Retiring/Acting PCC Lisa Oldroyd [email protected] Cleveland PCC candidate Steve Turner [email protected] steviet1610 Conservative Cleveland PCC candidate Paul Williams [email protected] PaulWilliamsLAB Labour Cumbria PCC -

Building Good Relationships Between Children and the Police

“It’s all about trust”: Building good relationships between children and the police Report of the inquiry held by the All Party Parliamentary Group for Children 2013-2014 About the All Party Parliamentary Group for Children The All Party Parliamentary Group for Children (APPGC) is a group of MPs and Peers with an interest in children’s issues and securing effective policies for children. The APPGC holds regular meetings on current issues affecting children and young people, and works strategically to raise the profile of children’s needs and concerns in Parliament. As well as inviting representatives of child-focused voluntary and statutory organisations and government departments to attend meetings, the APPGC hears directly from children and young people to take their views into consideration. All Party Parliamentary Group for Children mission statement: ‘To raise greater awareness in the Houses of Parliament on aspects of the well-being of the nation’s children aged 0-18 years, and our obligations under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child; and to work with children, young people, children’s organisations, and politicians from all sides to promote first-class government policy for children’. The Officers of the APPG for Children Chair: Baroness Massey of Darwen Vice-Chairs: Baroness Blood of Blackwatertown, Bill Esterson MP for Sefton Central, Tim Loughton MP for East Worthing and Shoreham, Baroness Walmsley of West Derby Secretary: Baroness Howarth of Breckland Treasurer: Earl of Listowel The National Children’s Bureau provides the secretariat for the All Party Parliamentary Group for Children. Clerk: Heather Ransom, 020 7843 6013, [email protected] Registered Charity Number 258825. -

Engaging with Your Local Policing Bodies

Engaging with your local policing bodies A briefing to help Friends who wish to engage with their Police and Crime Commissioners in England and Wales and with the Police Authority in Scotland. Police and Crime Commissioners (PCCs) are democratically elected, salaried, public servants responsible for policing and community safety in their local area. In 2012 they replaced local Police Authorities in England and Wales. The first Police and Crime Commissioners were elected in November 2012 for a four year term. Creating this new elected post is intended to make the function more accountable to the public. Democratic accountability means that the public should be involved in debate about the provision of services. Collectively Police and Crime Commissioners also represent the way in which policing develops in England and Wales. Under new legislation proposed in 2016 Police and Crime Commissioners in England will also be required to work more closely with the local fire and rescue services. In some cases they will be able to take over the responsibility for both those services. The Westminster government is also exploring how Police and Crime Commissioners could be more involved in the wider criminal justice system. Since 2012 policing is London is overseen by the Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime and a Deputy Mayor for Policing and Crime who has most of the powers and duties of a Police and Crime Commissioner. From May 2017 Greater Manchester’s elected mayor will take on the responsibilities of Police and Crime Commissioner for the area. Meanwhile they are being carried by the interim Mayor, appointed in 2015.