New Zealand Plants in Australian Gardens Stuart Read

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kells Bay Nursery

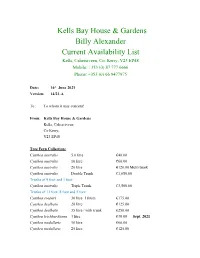

Kells Bay House & Gardens Billy Alexander Current Availability List Kells, Cahersiveen, Co. Kerry, V23 EP48 Mobile: +353 (0) 87 777 6666 Phone: +353 (0) 66 9477975 Date: 16th June 2021 Version: 14/21-A To : To whom it may concern! From: Kells Bay House & Gardens Kells, Caherciveen Co Kerry, V23 EP48 Tree Fern Collection: Cyathea australis 5.0 litre €40.00 Cyathea australis 10 litre €60.00 Cyathea australis 20 litre €120.00 Multi trunk Cyathea australis Double Trunk €1,650.00 Trunks of 9 foot and 1 foot Cyathea australis Triple Trunk €3,500.00 Trunks of 11 foot, 8 foot and 5 foot Cyathea cooperi 30 litre 180cm €175.00 Cyathea dealbata 20 litre €125.00 Cyathea dealbata 35 litre / with trunk €250.00 Cyathea leichhardtiana 3 litre €30.00 Sept. 2021 Cyathea medullaris 10 litre €60.00 Cyathea medullaris 25 litre €125.00 Cyathea medullaris 35 litre / 20-30cm trunk €225.00 Cyathea medullaris 45 litre / 50-60cm trunk €345.00 Cyathea tomentosisima 5 litre €50.00 Dicksonia antarctica 3.0 litre €12.50 Dicksonia antarctica 5.0 litre €22.00 These are home grown ferns naturalised in Kells Bay Gardens Dicksonia antarctica 35 litre €195.00 (very large ferns with emerging trunks and fantastic frond foliage) Dicksonia antarctica 20cm trunk €65.00 Dicksonia antarctica 30cm trunk €85.00 Dicksonia antarctica 60cm trunk €165.00 Dicksonia antarctica 90cm trunk €250.00 Dicksonia antarctica 120cm trunk €340.00 Dicksonia antarctica 150cm trunk €425.00 Dicksonia antarctica 180cm trunk €525.00 Dicksonia antarctica 210cm trunk €750.00 Dicksonia antarctica 240cm trunk €925.00 Dicksonia antarctica 300cm trunk €1,125.00 Dicksonia antarctica 360cm trunk €1,400.00 We have lots of multi trunks available, details available upon request. -

RECORDS of the HAWAII BIOLOGICAL SURVEY for 1995 Part 2: Notes1

RECORDS OF THE HAWAII BIOLOGICAL SURVEY FOR 1995 Part 2: Notes1 This is the second of two parts to the Records of the Hawaii Biological Survey for 1995 and contains the notes on Hawaiian species of plants and animals including new state and island records, range extensions, and other information. Larger, more compre- hensive treatments and papers describing new taxa are treated in the first part of this Records [Bishop Museum Occasional Papers 45]. New Hawaiian Pest Plant Records for 1995 PATRICK CONANT (Hawaii Dept. of Agriculture, Plant Pest Control Branch, 1428 S King St, Honolulu, HI 96814) Fabaceae Ulex europaeus L. New island record On 6 October 1995, Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources, Division of Forestry and Wildlife employee C. Joao submitted an unusual plant he found while work- ing in the Molokai Forest Reserve. The plant was identified as U. europaeus and con- firmed by a Hawaii Department of Agriculture (HDOA) nox-A survey of the site on 9 October revealed an infestation of ca. 19 m2 at about 457 m elevation in the Kamiloa Distr., ca. 6.2 km above Kamehameha Highway. Distribution in Wagner et al. (1990, Manual of the flowering plants of Hawai‘i, p. 716) listed as Maui and Hawaii. Material examined: MOLOKAI: Molokai Forest Reserve, 4 Dec 1995, Guy Nagai s.n. (BISH). Melastomataceae Miconia calvescens DC. New island record, range extensions On 11 October, a student submitted a leaf specimen from the Wailua Houselots area on Kauai to PPC technician A. Bell, who had the specimen confirmed by David Lorence of the National Tropical Botanical Garden as being M. -

The Endemic Tree Corynocarpus Laevigatus (Karaka) As a Weedy Invader in Forest Remnants of Southern North Island, New Zealand

New Zealand Journal of Botany ISSN: 0028-825X (Print) 1175-8643 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tnzb20 The endemic tree Corynocarpus laevigatus (karaka) as a weedy invader in forest remnants of southern North Island, New Zealand J.A. Costall , R.J. Carter , Y. Shimada , D. Anthony & G. L. Rapson To cite this article: J.A. Costall , R.J. Carter , Y. Shimada , D. Anthony & G. L. Rapson (2006) The endemic tree Corynocarpus laevigatus (karaka) as a weedy invader in forest remnants of southern North Island, New Zealand, New Zealand Journal of Botany, 44:1, 5-22, DOI: 10.1080/0028825X.2006.9513002 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0028825X.2006.9513002 Published online: 17 Mar 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 253 View related articles Citing articles: 8 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tnzb20 Download by: [203.173.191.20] Date: 05 August 2017, At: 07:54 New Zealand Journal of Botany, 2006, Vol. 44: 5-22 5 0028-825X/06/4401-0005 © The Royal Society of New Zealand 2006 The endemic tree Corynocarpus laevigatus (karaka) as a weedy invader in forest remnants of southern North Island, New Zealand J. A. COSTALL North Island, South Island, and the Kermadec and R. J. CARTER Chatham Islands, involving elimination or control, depending on local cultural values. Y. SHIMADA D.ANTHONY Keywords competition; Corynocarpus laevig- G. L. RAPSON* atus; ethnobotany; invasion; forest regeneration; Ecology Group fragment; homogenisation; New Zealand; remnant; Institute of Natural Resources seedling; weed; woody Massey University Private Bag 11222 Palmerston North, New Zealand INTRODUCTION *Author for correspondence. -

Contrasting Bacterial Communities in Two Indigenous Chionochloa (Poaceae) Grassland Soils in New Zealand

RESEARCH ARTICLE Contrasting bacterial communities in two indigenous Chionochloa (Poaceae) grassland soils in New Zealand Jocelyn C. Griffith1, William G. Lee2, David A. Orlovich1, Tina C. Summerfield1* 1 Department of Botany, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, 2 Landcare Research, Dunedin, New Zealand * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract a1111111111 a1111111111 The cultivation of grasslands can modify both bacterial community structure and impact on a1111111111 nutrient cycling as well as the productivity and diversity of plant communities. In this study, two pristine New Zealand grassland sites dominated by indigenous tall tussocks (Chiono- chloa pallens or C. teretifolia) were examined to investigate the extent and predictability of variation of the bacterial community. The contribution of free-living bacteria to biological OPEN ACCESS nitrogen fixation is predicted to be ecologically significant in these soils; therefore, the diazo- Citation: Griffith JC, Lee WG, Orlovich DA, trophic community was also examined. The C. teretifolia site had N-poor and poorly-drained Summerfield TC (2017) Contrasting bacterial peaty soils, and the C. pallens had N-rich and well-drained fertile soils. These soils also dif- communities in two indigenous Chionochloa (Poaceae) grassland soils in New Zealand. PLoS fer in the proportion of organic carbon (C), Olsen phosphorus (P) and soil pH. The nutrient- ONE 12(6): e0179652. https://doi.org/10.1371/ rich soils showed increased relative abundances of some copiotrophic bacterial taxa (includ- journal.pone.0179652 ing members of the Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes phyla). Other copiotrophs, Editor: Brenda A Wilson, University of Illinois at Actinobacteria and the oliogotrophic Acidobacteria showed increased relative abundance in Urbana-Champaign, UNITED STATES nutrient-poor soils. -

Apoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera). Fauna of New Zealand 57, 295 Pp. Donovan, B. J. 2007

Donovan, B. J. 2007: Apoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera). Fauna of New Zealand 57, 295 pp. EDITORIAL BOARD REPRESENTATIVES OF L ANDCARE R ESEARCH Dr D. Choquenot Landcare Research Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand Dr R. J. B. Hoare Landcare Research Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand REPRESENTATIVE OF UNIVERSITIES Dr R.M. Emberson c/- Bio-Protection and Ecology Division P.O. Box 84, Lincoln University, New Zealand REPRESENTATIVE OF M USEUMS Mr R.L. Palma Natural Environment Department Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa P.O. Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand REPRESENTATIVE OF OVERSEAS I NSTITUTIONS Dr M. J. Fletcher Director of the Collections NSW Agricultural Scientific Collections Unit Forest Road, Orange NSW 2800, Australia * * * SERIES EDITOR Dr T. K. Crosby Landcare Research Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand Fauna of New Zealand Ko te Aitanga Pepeke o Aotearoa Number / Nama 57 Apoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera) B. J. Donovan Donovan Scientific Insect Research, Canterbury Agriculture and Science Centre, Lincoln, New Zealand [email protected] Manaaki W h e n u a P R E S S Lincoln, Canterbury, New Zealand 2007 4 Donovan (2007): Apoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera) Copyright © Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd 2007 No part of this work covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means (graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping information retrieval systems, or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Cataloguing in publication Donovan, B. J. (Barry James), 1941– Apoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera) / B. J. Donovan – Lincoln, N.Z. : Manaaki Whenua Press, Landcare Research, 2007. (Fauna of New Zealand, ISSN 0111–5383 ; no. -

Chionochloa Flavicans F. Temata

Chionochloa flavicans f. temata COMMON NAME Te Mata Peak Snow Tussock SYNONYMS None (first described in 1991) FAMILY Poaceae AUTHORITY Chionochloa flavicans f. temata Connor FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Native ENDEMIC TAXON Yes ENDEMIC GENUS No ENDEMIC FAMILY No STRUCTURAL CLASS Grasses CHROMOSOME NUMBER 2n = 42 CURRENT CONSERVATION STATUS 2012 | At Risk – Naturally Uncommon | Qualifiers: OL PREVIOUS CONSERVATION STATUSES 2009 | At Risk – Naturally Uncommon | Qualifiers: OL 2004 | Range Restricted DISTRIBUTION Endemic. North Island, Hawkes Bay, where it is only known from Te Mata Peak, Havelock North. HABITAT Confined to limestone cliffs where it can at times be locally dominant. FEATURES Tall, rather stout, often sprawling, flabellate tussock with persistent leaves and sheaths. Leaf-sheath to 150 mm, pinkish or purplish, chartaceous, entire, becoming fibrous, keeled, glabrous or with a few long hairs, apical tuft of hairs to 1 mm. Ligule to 0.7 mm. Leaf-blade to 750 × 8 mm, dark green, often distinctly glaucous, keeled, persistent, glabrous except for some short hairs above ligule and prickle-teeth on margins and abaxially at apex. Culm to 1.5 m, internodes glabrous. Inflorescence to 300 mm, clavate, dense and compact, not naked below; rachis smooth below, branches and pedicels densely scabrid and with some long hairs at branch axils. Spikelets of up to 4 distant florets. Glumes to 4 mm, broad, shallowly bifid, sometimes purpled, margins ciliate, prickle-teeth adaxially above, < nearest lemma lobes; lower 3-nerved, upper 5-nerved. Lemma to 4 mm, shorter and broader than typical form; hairs dense on margin, few aside central nerve, rarely reaching sinus, prickle-teeth above adaxially and abaxially on nerves; lateral lobes to 0.2 mm, conspicuously awned adjacent to a small lobe; central awn to 6 mm, reflexed, column absent. -

<I>Plagianthus</I> (Malveae, Malvaceae)

Systematic Botany (2011), 36(2): pp. 405–418 © Copyright 2011 by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists DOI 10.1600/036364411X569589 Phylogeny and Character Evolution in the New Zealand Endemic Genus Plagianthus (Malveae, Malvaceae) Steven J. Wagstaff 1 , 3 and Jennifer A. Tate 2 1 Allan Herbarium, Landcare Research, PO Box 40, Lincoln 7640, New Zealand 2 Massey University, Institute of Molecular Biosciences, Private Bag 11222, Palmerston North, New Zealand 3 Author for correspondence ([email protected]) Communicating Editor: Lúcia Lohmann Abstract— As presently circumscribed, Plagianthus includes two morphologically distinct species that are endemic to New Zealand. Plagianthus divaricatus , a divaricate shrub, is a dominant species in coastal saline shrub communities, whereas P. regius is a tree of lowland and montane forests. Results from independent analyses of ITS and 5′ trnK / matK sequences are congruent, and when combined provide a robust framework to study character evolution. Our findings suggest the ancestor of Plagianthus originated in Australia where the sister gen- era Asterotrichion and Gynatrix are presently distributed. The stem age of Plagianthus was estimated at 7.3 (4.0–14.0) million years ago (Ma) and the crown radiation at 3.9 (1.9–8.2) Ma. Most of the characters optimized onto the molecular phylogeny were shared with source lineages from Australia and shown to be plesiomorphic. Only the divaricate branching pattern characteristic of Plagianthus divaricatus was acquired after the lineage became established in New Zealand and shown to be apomorphic. The initial Plagianthus founders were shrubs or small trees with deciduous leaves and small inconspicuous dioecious flowers. -

Waipa District Development and Subdivision Manual

Table of Contents Waipa District Development and Subdivision Manual Waipa District Development and Subdivision Manual 2015 Page 1 How to Use the Manual How to Use the Manual Please note that Waipa District Council has no controls over the way your electronic device prints the electronic version of the Manual and cannot guarantee that it will be consistent with the published version of the Manual. Version Control Version Date Updated By Section / Page # and Details 1.0 November 2012 Administrator Document approved by Council. 2.0 August 2013 Development Engineer Whole document updated to reflect OFI forms received. 2.1 September 2013 Development Engineer Whole document updated 2.2 August 2014 Development Engineer Whole document updated to reflect feedback from internal review. 2.3 December 2014 Development Engineer Whole document approved by Asset Managers 2.4 January 2015 Administrator Whole document renumbered and formatted. 2.5 May 2015 Administrator Document approved by Council. Page 2 Waipa District Development and Subdivision Manual 2015 Table of Contents Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ 3 Part 1: Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 5 Part 2: General Information ............................................................................................................ 7 Volume 1: Subdivision and Land Use Processes -

Otanewainuku ED (Report Prepared on 13 August 2013)

1 NZFRI collection wish list for Otanewainuku ED (Report prepared on 13 August 2013) Fern Ally Isolepis cernua Lycopodiaceae Isolepis inundata Lycopodium fastigiatum Isolepis marginata Lycopodium scariosum Isolepis pottsii Psilotaceae Isolepis prolifera Tmesipteris lanceolata Lepidosperma australe Lepidosperma laterale Gymnosperm Schoenoplectus pungens Cupressaceae Schoenoplectus tabernaemontani Chamaecyparis lawsoniana Schoenus apogon Cupressus macrocarpa Schoenus tendo Pinaceae Uncinia filiformis Pinus contorta Uncinia gracilenta Pinus patula Uncinia rupestris Pinus pinaster Uncinia scabra Pinus ponderosa Hemerocallidaceae Pinus radiata Dianella nigra Pinus strobus Phormium cookianum subsp. hookeri Podocarpaceae Phormium tenax Podocarpus totara var. totara Iridaceae Prumnopitys taxifolia Crocosmia xcrocosmiiflora Libertia grandiflora Monocotyledon Libertia ixioides Agapanthaceae Watsonia bulbillifera Agapanthus praecox Juncaceae Alliaceae Juncus articulatus Allium triquetrum Juncus australis Araceae Juncus conglomeratus Alocasia brisbanensis Juncus distegus Arum italicum Juncus edgariae Lemna minor Juncus effusus var. effusus Zantedeschia aethiopica Juncus sarophorus Arecaceae Juncus tenuis var. tenuis Rhopalostylis sapida Luzula congesta Asparagaceae Luzula multiflora Asparagus aethiopicus Luzula picta var. limosa Asparagus asparagoides Orchidaceae Cordyline australis x banksii Acianthus sinclairii Cordyline banksii x pumilio Aporostylis bifolia Asteliaceae Corunastylis nuda Collospermum microspermum Diplodium alobulum Commelinaceae -

RHS the Garden Magazine Index 2020

GardenThe INDEX 2020 Volume 145, Parts 1–12 Index 2020 January 2020 February 2020 March 2020 April 2020 May 2020 June 2020 1 2 3 4 5 6 Coloured numbers campestre ‘William ‘Voodoo’ 9: 78 ‘Kaleidoscope’ lauterbachiana Plas Brondanw, North in bold before the page Caldwell’ 3: 32, 32 ‘Zwartkop’ 7: 22, 22; 11: 46, 46 1: 56, 57 Wales 12: 38–42, 38–42 number(s) denote the x freemanii Autumn 8: 54, 54 ‘Lavender Lady’ 6: 12, macrorrhizos 11: 33, 33 Andrews, Susyn, on: part number (month). Blaze (‘Jeffersred’) Aeschynanthus 3: 138 12; 11: 46–47, 47 micholitziana 2: 78 hollies, AGM cultivars Each part is paginated 10: 14, 14–15 Aesculus ‘Macho Mocha’ Aloe Safari Sunrise (‘X5’) 12: 31, 31 separately. griseum 1: 49; 2: 14, 14– hippocastanum 11: 46, 47 6: 12, 12 Anemone: 15; 11: 34, 35; 12: 10, 10; ‘Hampton Court ‘Mayan Queen’ 11: 46 Aloysia: ‘Frilly Knickers’ 9: 7, 7 Numbers in italics 12: 83 Gold’ 3: 89, 89 ‘Pineapple Express’ citrodora (lemon Wild Swan denote an image. micrantham 10: 80 ‘Wisselink’ 3: 89, 89 11: 47 verbena) 6: 87, 87, 88; (‘Macane001’) 5: 74, palmatum 4: 74–75; x neglecta ‘Silver Fox’ 11: 47 to infuse gin 4: 82, 83 74, 76 Where a plant has a 12: 65, 65 ‘Erythroblastos’ Aglaonema (Chinese gratissima angelica root to infuse Trade Designation ‘Garnet’ 10: 27, 27 3: 88, 88 evergreen): 1: 57; 7: 34, (whitebrush or gin 4: 82, 82 (also known as a selling platanoides Agapanthus: 5: 82, 83 34; 12: 32, 32 spearmint verbena) Angelonia Serena Series name) it is typeset in ‘Walderseei’ 3: 87, 87 ‘Blue Dot 9: 109 ‘King of Siam’ 1: 56, 57 6: 86, 88 8: 16, 17 a different font to pseudoplatanus ‘Bressingham Blue’ pictum ‘Tricolor’ Alstroemeria: angel’s trumpet (see distinguish it from the ‘Brilliantissimum’ 9: 109 1: 44, 45 Indian Summer Brugmansia) cultivar name (shown 3: 86, 86–87 ‘Cally Blue 9: 109 Agrostis nebulosa (‘Tesronto’) 8: 16, 16 Angwin, Kirsty, on: in ‘Single Quotes’). -

Plant Charts for Native to the West Booklet

26 Pohutukawa • Oi exposed coastal ecosystem KEY ♥ Nurse plant ■ Main component ✤ rare ✖ toxic to toddlers coastal sites For restoration, in this habitat: ••• plant liberally •• plant generally • plant sparingly Recommended planting sites Back Boggy Escarp- Sharp Steep Valley Broad Gentle Alluvial Dunes Area ment Ridge Slope Bottom Ridge Slope Flat/Tce Medium trees Beilschmiedia tarairi taraire ✤ ■ •• Corynocarpus laevigatus karaka ✖■ •••• Kunzea ericoides kanuka ♥■ •• ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• Metrosideros excelsa pohutukawa ♥■ ••••• • •• •• Small trees, large shrubs Coprosma lucida shining karamu ♥ ■ •• ••• ••• •• •• Coprosma macrocarpa coastal karamu ♥ ■ •• •• •• •••• Coprosma robusta karamu ♥ ■ •••••• Cordyline australis ti kouka, cabbage tree ♥ ■ • •• •• • •• •••• Dodonaea viscosa akeake ■ •••• Entelea arborescens whau ♥ ■ ••••• Geniostoma rupestre hangehange ♥■ •• • •• •• •• •• •• Leptospermum scoparium manuka ♥■ •• •• • ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• ••• Leucopogon fasciculatus mingimingi • •• ••• ••• • •• •• • Macropiper excelsum kawakawa ♥■ •••• •••• ••• Melicope ternata wharangi ■ •••••• Melicytus ramiflorus mahoe • ••• •• • •• ••• Myoporum laetum ngaio ✖ ■ •••••• Olearia furfuracea akepiro • ••• ••• •• •• Pittosporum crassifolium karo ■ •• •••• ••• Pittosporum ellipticum •• •• Pseudopanax lessonii houpara ■ ecosystem one •••••• Rhopalostylis sapida nikau ■ • •• • •• Sophora fulvida west coast kowhai ✖■ •• •• Shrubs and flax-like plants Coprosma crassifolia stiff-stemmed coprosma ♥■ •• ••••• Coprosma repens taupata ♥ ■ •• •••• •• -

Bio 308-Course Guide

COURSE GUIDE BIO 308 BIOGEOGRAPHY Course Team Dr. Kelechi L. Njoku (Course Developer/Writer) Professor A. Adebanjo (Programme Leader)- NOUN Abiodun E. Adams (Course Coordinator)-NOUN NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA BIO 308 COURSE GUIDE National Open University of Nigeria Headquarters 14/16 Ahmadu Bello Way Victoria Island Lagos Abuja Office No. 5 Dar es Salaam Street Off Aminu Kano Crescent Wuse II, Abuja e-mail: [email protected] URL: www.nou.edu.ng Published by National Open University of Nigeria Printed 2013 ISBN: 978-058-434-X All Rights Reserved Printed by: ii BIO 308 COURSE GUIDE CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ……………………………………......................... iv What you will Learn from this Course …………………............ iv Course Aims ……………………………………………............ iv Course Objectives …………………………………………....... iv Working through this Course …………………………….......... v Course Materials ………………………………………….......... v Study Units ………………………………………………......... v Textbooks and References ………………………………........... vi Assessment ……………………………………………….......... vi End of Course Examination and Grading..................................... vi Course Marking Scheme................................................................ vii Presentation Schedule.................................................................... vii Tutor-Marked Assignment ……………………………….......... vii Tutors and Tutorials....................................................................... viii iii BIO 308 COURSE GUIDE INTRODUCTION BIO 308: Biogeography is a one-semester, 2 credit- hour course in Biology. It is a 300 level, second semester undergraduate course offered to students admitted in the School of Science and Technology, School of Education who are offering Biology or related programmes. The course guide tells you briefly what the course is all about, what course materials you will be using and how you can work your way through these materials. It gives you some guidance on your Tutor- Marked Assignments. There are Self-Assessment Exercises within the body of a unit and/or at the end of each unit.