Schedule Two of the 2008 Constitution Avenues for Reform and Decentralization and Steps Towards a Federal System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myanmar's Spring Revolution

EUROPEAN POLICY BRIEF MYANMAR ’S SPRING REVOLUTION : A PEOPLE ’S REVOLUTION Myanmar’s Spring Revolution is a grassroots, bottom-to-top nationwide resistance against the military ruling class that retook state power in February 2021. It is unprecedented in scale, fascinating in form and shows a profound societal change within the country. Michal Lubina , April 2021 INTRODUCTION A People’s revolution Myanmar’s Spring Revolution is a grassroots, bottom-to-top nationwide resistance against the military ruling class that retook state power in February 2021. It is unprecedented in scale, fascinating in form and shows a profound societal change within the country. EVIDENCE AND ANALYSIS The end of hermit country Burma has traditionally been called a hermit country 1 – a designation not uncommon in Asia (Bhutan and especially Korea were similarly named), yet very fitting in the case of Myanmar. Precolonial Burmese kingdoms were generally inward-looking, with periods of sometimes spectacular external expeditions being exceptions rather than the rule. Some believed Burma’s isolation was due to economic self-sufficiency, others ascribed it to geography. Still others looked for explanations in the cultural realm, believing - like Aung San Suu Kyi in her early writings 2 - that Buddhism made Burmese uninterested in foreign ideas. Whatever the reasons, it was only the colonial period that brought Burma into the global, capitalist world, however imperfectly: “Burma had been thrown open to the world, but the world had not been opened up to Burma.” 3 This forceful incursion inflicted wounds that never healed. That is why after the creative and chaotic decade of the 1950s (somewhat similar to the last ten years), Burma reverted to self-isolation after the 1962 1 Gustaaf Houtman, Mental Culture in Burmese Crisis Politics: Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy, ISLCAA Tokyo 1999, p. -

The Third Force in Myanmar

The Third Force and the Architecture of Civil Society -State Relations in the Transition in Myanmar, 2008-2017 The Third Force and the Architecture of Civil Society -State Relations in the Transition in Myanmar, 2008-2017 ___________________________ Mael Raynaud Independent Analyst [email protected] Abstract Myanmar has embarked on a political transition in 2011, a transition better described here as a transition to a hybrid system, with elements of democracy and elements of a military rule. Building on the existing literature on transitions, political crises, civil society, and political influence, the present article attempts to define what the role of civil society has been in this process. Using the author ‘s concepts of a social stupa, in Myanmar, and of the "architecture of civil society-state relations", observed through various "points วารสาร สิทธิและสันติศึกษา ปีที่ 4 ฉบับที่ 2 of contacts" between the two, the author sets an argument that political influence is stronger in the points of contact at the top of the social stupa where the civil society elite meets political elite. In that sense, civil society leaders can be seen as groups that organically channel the voice of civil society to those in power. This perspective explains the strategy behind the Third Force, a group of civil society leaders that gained influence in the wake of cyclone Nargis in 2008 and had a significant impact on the political process, and officially or semi-officially became advisors to President U Thein Sein from 2011 to 2016. The article then argues that the NLD government has cut much of these ties, but that civil society-state relations have nevertheless been profoundly re-shaped in the last decade. -

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar Asia Report N°312 | 28 August 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. A Legacy of Division ......................................................................................................... 4 A. Who Lives in Myanmar? ............................................................................................ 4 B. Those Who Belong and Those Who Don’t ................................................................. 5 C. Contemporary Ramifications..................................................................................... 7 III. Liberalisation and Ethno-nationalism ............................................................................. 9 IV. The Militarisation of Ethnicity ......................................................................................... 13 A. The Rise and Fall of the Kaungkha Militia ................................................................ 14 B. The Shanni: A New Ethnic Armed Group ................................................................. 18 C. An Uncertain Fate for Upland People in Rakhine -

Total Detention, Charge and Fatality Lists

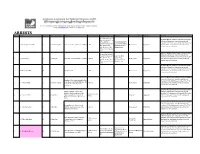

ARRESTS No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark S: 8 of the Export and Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Import Law and S: 25 leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and of the Natural Superintendent Kyi President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Disaster Management Lin of Special Branch, 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F General Aung San State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and law, Penal Code - Dekkhina District regions were also detained. 505(B), S: 67 of the Administrator Telecommunications Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD S: 25 of the Natural leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Disaster Management Superintendent President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s law, Penal Code - Myint Naing, 2 (U) Win Myint M U Tun Kyin President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and 505(B), S: 67 of the Dekkhina District regions were also detained. Telecommunications Administrator Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Union Assembly, the President U Win Myint were detained. -

Situation Analysis of Myanmar's Region and State Hluttaws

1 Authors This research product would not have been possible without Carl DeFaria the great interest and cooperation of Hluttaw and government representatives in Mon, Mandalay, Shan and Tanintharyi Philipp Annawitt Region and States. We would like express our heartfelt thanks to Daw Tin Ei, Speaker of the Mon State Hluttaw, U Aung Kyaw Research Team Leader Oo, Speaker of the Mandalay Region Hluttaw, U Sai Lone Seng, Aung Myo Min Speaker of the Shan State Hluttaw, and U Khin Maung Aye, Speaker of the Tanintharyi Region Hluttaw, who participated enthusiastically in this project and made themselves, their Researcher and Technical Advisor MPs and staff available for interviews, and who showed great Janelle San ownership throughout the many months of review and consultation on the findings and resulting recommendations. We also wish to thank Chief Ministers U Zaw Myint Maung, Technical Advisor Dr Aye Zan, U Linn Htut, and Dr. Le Le Maw for making Warren Cahill themselves and/or their ministers and cabinet members available for interviews, and their Secretaries of Government who facilitated travel authorizations and set up interviews Assistant Researcher with township officials. T Nang Seng Pang In particular, we would like to thank the eight constituency Research Team Members MPs interviewed for this research who took several days out of their busy schedule to organize and accompany our research Hlaing Yu Aung team on visits to often remote parts of their constituencies Min Lawe and organized the wonderful meetings with ward and village tract administrators, household heads and community Interpreters members that proved so insightful for this research and made our picture of the MP’s role in Region and State governance Dr. -

Norway's Constructive Engagement in Myanmar

Master’s Thesis 2016 30 ECTS Department of International Environment and Development Studies (Noragric) Norway’s Constructive Engagement in Myanmar. A small state as norm entrepreneur. Birgitte Moe Olsen Master of Science in International Relations I The Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric, is the international gateway for the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU). Eight departments, associated research institutions and the Norwegian College of Veterinary Medicine in Oslo. Established in 1986, Noragric’s contribution to international development lies in the interface between research, education (Bachelor, Master and PhD programmes) and assignments. The Noragric Master thesis are the final theses submitted by students in order to fulfil the requirements under the Noragric Master programme “International Environmental Studies”, “International Development Studies” and “International Relations”. The findings in this thesis do not necessarily reflect the views of Noragric. Extracts from this publication may only be reproduced after prior consultation with the author and on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation contact Noragric. © Birgitte Moe Olsen, December 2016 [email protected] Noragric Department of International Environment and Development Studies P.O. Box 5003 N-1432 Ås Norway Tel.: +47 64 96 52 00 Fax: +47 64 96 52 01 Internet: http://www.nmbu.no/noragric II Declaration I, Birgitte Moe Olsen, declare that this thesis is a result of my research investigations and findings. Sources of information other than my own have been acknowledged and a reference list has been appended. This work has not been previously submitted to any other university for award of any type of academic degree. -

“Pre-Election Monitoring Study in Rakhine State”

“Pre-Election Monitoring Study in Rakhine State” Table of Contents KEY FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................................... 2 1. BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 5 1.1. POLITICAL PARTY LANDSCAPE IN RAKHINE STATE............................................................................ 7 1.2. INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS ON FREE AND FAIR ELECTIONS .............................................................. 8 1.3. ELECTORAL SYSTEM IN MYANMAR ................................................................................................. 10 2. OBJECTIVE AND SCOPE OF THE STUDY ..................................................................................... 11 1. METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................................ 11 1.1. SAMPLING ...................................................................................................................................... 11 1.2. RESEARCH PROCESS ........................................................................................................................ 12 1.3. LIMITATION OF STUDY .................................................................................................................... 12 2. FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................................ -

Moving Beyond Hermit Kingdoms. Korea in Burma's Foreign Policy

XII: 2015 nr 3 Michał Lubina MOVING BEYOND HERMIT KINGDOMS. KOREA IN BURMA’S FOREIGN POLICY Burma (Myanmar)1 has been called the Hermit Kingdom. Korea (more recently North Korea) has been labeled similarly. This is correct to some extend, given the fact that in both countries hermits played an important role in the political culture. It is interesting, therefore, to ask whether these similar cultural patters have had any effect on their relations. Has Korea been important to Burma? What place have Koreans had in Burma’s foreign policy? Introduction This article traces the most important aspects of Korea-Burma relations. It starts with the conceptual introduction by showing the ideological spectrum of the Bur- mese elites’ political thinking. Then it describes the “hermit” cultural similarity between Burma and Korea. In its most important part this paper is intended to present the contemporary political relations between Koreas and Burma from the 1 The name of this country invokes many controversies. In June 1989, the State Law and Restoration Council (the new junta) changed the offi cial international designation of the country from “Burma” to “Myanmar” (“Myanmar” is the autonym of the ethnic majority since ancient times and has always been used internally). The usage of the country’s name has been politically controversial since then. Personally, I consider this question highly political and, given the fact that BOTH names – Burma and Myanmar – are of Burmese origin, quite ridiculous. I follow traditional naming in English and therefore use Burma throughout the article. 162 MICHAŁ LUBINA failed assassination of Chun Doo Hwan to the recent dynamics. -

List of Contents

List of Contents A. Pyidaungsu Hluttaw Pyithu Hlluttaw Election Results 2015, with historical Comparison Amyotha Hluttaw Election Results 2015, with historical Comparison Pyithu Hlluttaw Election Results 2015, with MP Information Amyotha Hluttaw Election Results 2015, with MP Information Political Party Representation in the Pyithu Hluttaw (December 2014) Pyithu Hluttaw Election Results 2015 Political Party Representation in the Amyotha Hluttaw (December 2014) Amyotha Hluttaw Election Results 2015 Pyithu Hluttaw Constituency Boundaries, 2015 Elections Amyotha Hluttaw Constituency Boundaries, 2015 Elections Eligible Voters per Pyithu Hluttaw Constituency, 2015 Elections Eligible Voters per Amyotha Hluttaw Constituency, 2015 Elections Candidates per Pyithu Hluttaw Constituency, 2015 Elections Candidates per Amyotha Hluttaw Constituency, 2015 Elections Turnout in the 2015 Elections Invalid Votes in the 2015 Elections Advance Votes in the 2015 Elections Transferred Votes in the 2015 Elections Areas where elections did not take place in 2010 / 2012 Election Cancellations 2010 – 2015 Sequence of 2015 Election Cancellations 2015 Election Cancellations & Vacant Seats B. State and Region Hluttaws State and Region Hluttaw Election Results 2015 (on Union level) State and Region Hluttaw Election Results 2015, with MP Information Political Party Representation Before Elections 2015, Ayeyarwady Region Hluttaw Election Results 2015, Ayeyarwady Region Hluttaw Political Party Representation Before Elections 2015, Bago Region Hluttaw Election Results 2015, -

Burma 2018 International Religious Freedom Report

BURMA 2018 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution guarantees every citizen “the right to freely profess and practice religion subject to public order, morality or health and to the other provisions of this Constitution.” The law prohibits speech or acts insulting or defaming any religion or religious beliefs; authorities used these laws to limit freedom of expression and press. Local and international experts said deeply woven prejudices led to abuses and discrimination against religious minorities by government and societal actors. It was sometimes difficult to categorize incidents as based solely on religious identity due to the close linkage between religion and ethnicity in the country. Violence, discrimination, and harassment against ethnic Rohingya in Rakhine State, who are nearly all Muslim, and other minority populations continued. Following the ethnic cleansing against the Rohingya that took place in 2017 and resulted in the displacement of more than 700,000 refugees to Bangladesh, Rohingya who remained in Burma continued to face an environment of particularly severe repression and restrictions on freedom of movement and access to education, healthcare, and livelihoods based on their ethnicity, religion, and citizenship status, according to the United Nations and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). In March the UN special rapporteur for human rights in Myanmar reported that the government appeared to be using starvation tactics against remaining Rohingya. On September 17, the UN Fact- Finding Mission, established by the UN Human Rights Council, published its final report on the country, which detailed atrocities committed by the military in Rakhine, Kachin, and Shan States, as well as other areas, and characterized the “genocidal intent” of the military’s 2017 operations in Rakhine State. -

A History of the Burma Socialist Party (1930-1964)

University of Wollongong Theses Collection University of Wollongong Theses Collection University of Wollongong Year A history of the Burma Socialist Party (1930-1964) Kyaw Zaw Win University of Wollongong Win, Kyaw Zaw, A history of the Burma Socialist Party (1930-1964), PhD thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2008. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/106 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/106 A HISTORY OF THE BURMA SOCIALIST PARTY (1930-1964) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy From University of Wollongong By Kyaw Zaw Win (BA (Q), BA (Hons), MA) School of History and Politics, Faculty of Arts July 2008 Certification I, Kyaw Zaw Win, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of History and Politics, Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Kyaw Zaw Win______________________ Kyaw Zaw Win 1 July 2008 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations and Glossary of Key Burmese Terms i-iii Acknowledgements iv-ix Abstract x Introduction xi-xxxiii Literature on the Subject Methodology Summary of Chapters Chapter One: The Emergence of the Burmese Nationalist Struggle (1900-1939) 01-35 1. Burmese Society under the Colonial System (1870-1939) 2. Patriotism, Nationalism and Socialism 3. Thakin Mya as National Leader 4. The Class Background of Burma’s Socialist Leadership 5. -

TERMS of REFERENCE Assignment Title Parliamentary Committee Specialist Type of Contract Framework Agreement Start/End Dates 5 Ma

TERMS OF REFERENCE Assignment Title Parliamentary Committee Specialist Type of Contract Framework Agreement Start/End Dates 5 May 2019 – 15 December 2020 Assignment Bracket Intermediate-level expert / Specialist Number of working days Up to 18 months / 360 days Supervisor Sub-national Parliament Specialist Duty Station Yangon, with travel to Nay Pyi Taw, Rakhine, Mon, Shan, Mandalay, and other Regions and States 1. Background The Constitution of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar (the Constitution) came into force in 2008. Chapter 4 of the Constitution establishes parliaments (Hluttaws) at two levels. The national level- Union (Pyidaungsu) Hluttaw comprises two Hluttaws, Pyithu Hluttaw (House of Representatives) and Amyotha Hluttaw (House of Nationalities), that are generally equal in status. The term of the Union Hluttaw is 5 years from the day of the first session of the Pyithu Hluttaw. The Constitution has also established sub- national Hluttaws comprising one Hluttaw for each of the fourteen Regions and States. The Union and Region/State Hluttaws are independent institutions with different political compositions and mandate, but their administrative support is provided by national-level civil service staff, under the guidance of the Permanent Secretary of the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw. Myanmar’s Hluttaws are very young institutions, currently in their second 5-year term, which has started in February 2016. Under UNDP’s Support to Effective Responsive Institutions (SERIP) and Strengthening Accountability and Rule of Law (SARL) projects, UNDP provides support to developing Myanmar’s Hluttaws committee systems and practices to ensure parliaments are able to use their committees in effective policy review, legislative review, budget review and oversight processes.