Trends in Southeast Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar Asia Report N°312 | 28 August 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. A Legacy of Division ......................................................................................................... 4 A. Who Lives in Myanmar? ............................................................................................ 4 B. Those Who Belong and Those Who Don’t ................................................................. 5 C. Contemporary Ramifications..................................................................................... 7 III. Liberalisation and Ethno-nationalism ............................................................................. 9 IV. The Militarisation of Ethnicity ......................................................................................... 13 A. The Rise and Fall of the Kaungkha Militia ................................................................ 14 B. The Shanni: A New Ethnic Armed Group ................................................................. 18 C. An Uncertain Fate for Upland People in Rakhine -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

Social Assessment for Ayeyarwady Region and Shan State

AND DEVELOPMENT May 2019 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized SOCIAL ASSESSMENT FOR AYEYARWADY REGION AND SHAN STATE Public Disclosure Authorized Myanmar: Maternal and Child Cash Transfers for Improved Nutrition 1 Myanmar: Maternal and Child Cash Transfers for Improved Nutrition Ministry of Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement May 2019 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 5 List of Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................... 9 List of Tables ................................................................................................................................... 10 List of BOXES ................................................................................................................................... 10 A. Introduction and Background....................................................................................................... 11 1 Objectives of the Social Assessment ................................................................................................11 2 Project Description ..........................................................................................................................11 3 Relevant Country and Sector Context..............................................................................................12 3.1 -

The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census SHAN STATE, KYAUKME DISTRICT Namtu Township Report

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census SHAN STATE, KYAUKME DISTRICT Namtu Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population October 2017 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Shan State, Kyaukme District Namtu Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population Office No.48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431062 www.dop.gov.mm October 2017 Figure 1 : Map of Shan State, showing the townships Namtu Township Figures at a Glance 1 Total Population 50,423 2 Population males 24,448 (48.5%) Population females 25,975 (51.5%) Percentage of urban population 26.4% Area (Km2) 1,689.0 3 Population density (per Km2) 29.9 persons Median age 25.8 years Number of wards 2 Number of village tracts 21 Number of private households 11,641 Percentage of female headed households 27.5% Mean household size 4.2 persons 4 Percentage of population by age group Children (0 – 14 years) 32.6% Economically productive (15 – 64 years) 62.3% Elderly population (65+ years) 5.1% Dependency ratios Total dependency ratio 60.5 Child dependency ratio 52.3 Old dependency ratio 8.2 Ageing index 15.6 Sex ratio (males per 100 females) 94 Literacy rate (persons aged 15 and over) 67.5% Male 71.8% Female 63.7% People with disability Number Per cent Any form of disability 3,082 6.1 Walking 1,035 2.1 Seeing 1,374 2.7 Hearing 1,137 2.3 Remembering 976 1.9 Type of Identity Card (persons aged 10 and over) Number Per cent Citizenship Scrutiny 28,204 71.4 Associate Scrutiny -

“Pre-Election Monitoring Study in Rakhine State”

“Pre-Election Monitoring Study in Rakhine State” Table of Contents KEY FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................................... 2 1. BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 5 1.1. POLITICAL PARTY LANDSCAPE IN RAKHINE STATE............................................................................ 7 1.2. INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS ON FREE AND FAIR ELECTIONS .............................................................. 8 1.3. ELECTORAL SYSTEM IN MYANMAR ................................................................................................. 10 2. OBJECTIVE AND SCOPE OF THE STUDY ..................................................................................... 11 1. METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................................ 11 1.1. SAMPLING ...................................................................................................................................... 11 1.2. RESEARCH PROCESS ........................................................................................................................ 12 1.3. LIMITATION OF STUDY .................................................................................................................... 12 2. FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................................ -

Burma 2018 International Religious Freedom Report

BURMA 2018 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution guarantees every citizen “the right to freely profess and practice religion subject to public order, morality or health and to the other provisions of this Constitution.” The law prohibits speech or acts insulting or defaming any religion or religious beliefs; authorities used these laws to limit freedom of expression and press. Local and international experts said deeply woven prejudices led to abuses and discrimination against religious minorities by government and societal actors. It was sometimes difficult to categorize incidents as based solely on religious identity due to the close linkage between religion and ethnicity in the country. Violence, discrimination, and harassment against ethnic Rohingya in Rakhine State, who are nearly all Muslim, and other minority populations continued. Following the ethnic cleansing against the Rohingya that took place in 2017 and resulted in the displacement of more than 700,000 refugees to Bangladesh, Rohingya who remained in Burma continued to face an environment of particularly severe repression and restrictions on freedom of movement and access to education, healthcare, and livelihoods based on their ethnicity, religion, and citizenship status, according to the United Nations and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). In March the UN special rapporteur for human rights in Myanmar reported that the government appeared to be using starvation tactics against remaining Rohingya. On September 17, the UN Fact- Finding Mission, established by the UN Human Rights Council, published its final report on the country, which detailed atrocities committed by the military in Rakhine, Kachin, and Shan States, as well as other areas, and characterized the “genocidal intent” of the military’s 2017 operations in Rakhine State. -

Burma's Northern Shan State and Prospects for Peace

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE PEACEBRIEF234 United States Institute of Peace • www.usip.org • Tel. 202.457.1700 • @usip September 2017 DAVID SCOTT MATHIESON Burma’s Northern Shan State Email: [email protected] and Prospects for Peace Summary • Increased armed conflict between the Burmese Army and several ethnic armed organizations in northern Shan State threaten the nationwide peace process. • Thousands of civilians have been displaced, human rights violations have been perpetrated by all parties, and humanitarian assistance is being increasingly blocked by Burmese security forces. • Illicit economic activity—including extensive opium and heroin production as well as transport of amphetamine stimulants to China and to other parts of Burma—has helped fuel the conflict. • The role of China as interlocutor between the government, the military, and armed actors in the north has increased markedly in recent months. • Reconciliation will require diverse advocacy approaches on the part of international actors toward the civilian government, the Tatmadaw, ethnic armed groups, and civil society. To facili- tate a genuinely inclusive peace process, all parties need to be encouraged to expand dialogue and approach talks without precondition. Even as Burma has “transitioned from decades Introduction of civil war and military rule Even as Burma has transitioned—beginning in late 2010—from decades of civil war and military to greater democracy, long- rule to greater democracy, long-standing and widespread armed conflict has resumed between several ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) and the Burmese armed forces (Tatmadaw). Early in standing and widespread 2011, a 1994 ceasefire agreement broke down as relations deterioriated in the wake of the National armed conflict has resumed.” League for Democracy government’s refusal to permit Kachin political parties to participate in the elections that ended the era of military rule in the country. -

Geology & Mineral Resources of Myanmar

Geology & Mineral Resources of Myanmar KYAW KYAW OHN Assistant Director (Geologist) DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGICAL SURVEY AND MINERAL EXPLORATION MINISTRY OF MINES 1 Introduction Organization Morpho-Tectonic Geology Mineral Occurrence Investment Cooperation Conclusion Belts of Setting of & Mining Activities Opportunities with Myanmar Myanmar in Myanmar International Myanmar is endowed with resources of arable land, natural gas, mineral deposits, fisheries, forestry and manpower. 2 Introduction Organization Morpho-Tectonic Geology Mineral Occurrence Investment Cooperation Conclusion Belts of Setting of & Mining Activities Opportunities with Myanmar Myanmar in Myanmar International Area : 678528 sq.km Coast Line : 2100 km Border : 4000 km NS Extend : 2200 km EW Extend : 950 km Population : >51millions(est:) Region : 7 State: : 7 Location : 10º N to 28º 30' 92º 30' E to 101º30' 3 Introduction Organization Morpho-Tectonic Geology Mineral Occurrence Investment Cooperation Conclusion Belts of Setting of & Mining Activities Opportunities with Myanmar Myanmar in Myanmar International Union Minister Deputy Minister No.(1) No.(2) Myanmar Myanmar Department of Geological Department Mining Mining Gems Pearl Survey &Mineral of Enterprise Enterprise Enterprise Enterprise Exploration Mines Lead Coal Gold Gems, Pearl Geological Mineral Zinc Lime stone Tin Jade Breeding Survey Policy Silver Industrial Tungsten & Cultivating Mineral formulation, Copper Minerals Rare Earth Jewelry Exploration Regulation Iron Manganese Titanium Laboratory measures Nickel Decorative -

Myanmar Overall Score: 53

Global Tobacco Industry Interference Index 2019 Myanmar Overall score: 53 I. Industry participation in policy development: required pictures and old pictures were still found The National Tobacco Control Board has been in the market. No action was found to be taken. constituted under the national tobacco control The Myanmar government is open and welcoming law of 2006. Although representatives from to foreign investment including BAT and JTI, and tobacco industries are not present in the Board most recently to Burma Tobacco Trading Co. for as members, the government will consider cigar production and tobacco growing. proposals from the tobacco industry in setting or implementing public health policies in relation IV. Unnecessary interaction with the tobacco to tobacco control. In 2017 the tobacco industry industry: There are no publicly available reports submitted a tobacco tax proposal for the tax of government officials attending social functions reform to the Internal Revenue Department and of the tobacco industry. EUROCHAM Myanmar Ministry of Planning and Finance. The Ministry has an anti-Illicit Trade group which has BAT acknowledged the receipt of the proposal and as a member. The objective of this group is “to co- indicated it will include it for consideration. ordinate regular consultation meetings between the group and the authorized government officials II. Tobacco industry-related CSR activities: A local to develop a shared understanding of challenges Cigarette Company, called Myanmar Kokang and issues.” Company Ltd. (MMK Cigarette Factory), at Muse, Northern Shan State, provided sponsorship V. Procedure for transparency measures: There is no through its distributor, Hexa Power Company Ltd., mechanism or rules for disclosure of government for the mini marathon and public walking event meetings with the tobacco industry. -

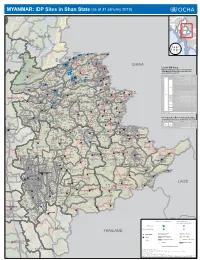

IDP Sites in Shan State (As of 31 January 2019)

MYANMAR: IDP Sites in Shan State (as of 31 January 2019) BHUTAN INDIA CHINA BANGLADESH Nay Pyi Taw LAOS KACHIN THAILAND Pang Hseng Man Kin (Kyu Koke) Monekoe SAGAING Kone Ma Na Maw Hteik 21 Nawt Ko Pu Wan Nam Kyar Mon Hon Tee Yi Hku Ngar Oe Nam War Manhlyoe 22 23 Nam Kut Char Lu Keng Aik Hpan Shwe Kyaung Kone U Yin Pu Nam Kat 36 (Manhero) Man Hin ☇ Muse Pa Kon War Yawng San Hsar Muse Konkyan Kun Taw 37 Man Mei ☇ Long Gam Man Ton ☇34 Tar Ku Ti Thea Chaung Namhkan 35 KonkyanTar Shan ☇ Man Set Kyu Pat 11 26 28 Au Myar Loi Mun Ton Bar 27 Yae Le Lin Lai 25 29 Hsi Hsar Hsin Keng Yan Long Keng CHINA Ho Nar Pang Mawng Long Htan Baing Law Se Long Nar Hpai Pwe Za Meik Khaw Taw HumLaukkaing Htin List of IDP Sites Aw Kar Pang Mu Shwe Htu Namhkan Kawng Hkam Nar Lel Se Kin 14 Bar Hpan Man Tet 15 Man Kyu Baing Bin Yan Bo (Lower) Nam Hum Tar Pong Ho Maw Ho Et Kyar Ti Lin Data provided by the Camp Coordination and Pang Hkan Hing Man Nar Hin Lai 4 Kutkai Nam Hu Man Sat Man Aw Mar Li Lint Ton Kwar 24 Camp Management (CCCM) Cluster based on Pin Kyein (Ywar Thit) Ho Pang 8 Hseng Hkawng Laukkaing Mabein 17 Man Hwei Si Ping Man Kaw Kaw Yi Hon Gyet Hopong Hpar Pyint Nar Ngu Long Htan update of 31 January 2018 Lawt Naw 9 Hko Tar Ma Waw 10 Tarmoenye Say Kaw Man Long Maw Han Loi Kan Ban Nwet Pying Kut Mabein Su Yway Namtit No. -

Winning Parties in Self-Administered Zones in the 2015 General Elections

Winning Parties in Self-Administered Zones in the 2015 General Elections Figure 1: Six Self-Administered Zones in Myanmar In Myanmar ethnic identities are represented by four different forms: ethnic states, self-administered areas, ethnic affairs ministers and constituencies won by ethnic parties. The 2008 Constitution stipulated 5 “Self-Administered Zones” for the Naga in the Sagaing Region, and Danu, Kokang, Palaung and Pao, as well as a larger “Self-Administered Division” for the Wa, in Shan State. The 2015 General Elections took place in Self-administered zones polling excerpt five townships in Wa Self- Administered Division: Mongmao, Pangwaun, Namphan, Pangsang and Mongla. In addition, some villages tracts in Hopang and Matman did not have elections either. Ta-Arng Palaung National Party and Pao National Organisation (PNO) won all the seats for Pyithu and State/Region Hluttaws in their respective self-administered zones. National League for Democracy (NLD) won all 3 seats for Pyithu Hluttaw in Naga self-administered zones and won 5 out of 6 seats for state/region hlutttaw. Union Solidarity and Development Party won all the seats in Kokang self-administered zones. In Danu self-administered zone, party preference was ambiguous since NLD and USDP shared seats for the state/region hluttaw. Although NLD is popular nationwide, ethnic parties, for example, PaO National Organization and Ta-Arng Palaung National Party, are also influential in self-administered zones. There is an internal ethnic division in the Wa case. As Myanmar is moving towards peace process, ethnic politics in election has become crucial and it is interesting to look at the winning parties in self-administered zones. -

Download (568Kb)

Mona Chettri, Michael Eilenberg (eds). (2020) Development Zones in Asian Borderlands. Amsterdam University Press: https://www.aup.nl/en/book/9789463726238/development- zones-in-asian-borderlands 6. Development Zones in Conflict-Affected Borderlands: The Case of Muse, Northern Shan State, Myanmar Patrick Meehan, Sai Aung Hla and Sai Kham Phu Abstract: How are development zones ‘made’ in conflict-affected borderlands? Addressing this question, this chapter explores the transformation of the Myanmar-China border town of Muse since 1988. Despite ongoing armed conflict in northern Myanmar, Muse has become the country’s most important border development zone and today handles more than 80% of licit overland Myanmar-China trade. It is also a key border hub in China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Policy narratives typically claim that borderland development and regional economic integration offer an antidote to violence, criminality, and illegal practices. This chapter challenges these narratives. It demonstrates how longstanding forms of informal public authority and illegality have become deeply embedded in the technologies of governance that have underpinned Muse’s rise. Keywords: Illicit economies; borderland development; informal governance; militias; illegal drugs; Belt and Road Initiative. 1 Mona Chettri, Michael Eilenberg (eds). (2020) Development Zones in Asian Borderlands. Amsterdam University Press: https://www.aup.nl/en/book/9789463726238/development- zones-in-asian-borderlands Informal Governance and Illegality in the making of Borderland Development Zones Since the late 1980s, borderland regions across Southeast Asia have increasingly been re- imagined as zones of economic opportunity that have the potential to stimulate national and regional development. Development discourses have promoted the ‘opening up’ of ‘marginal’ spaces to markets and capital alongside political projects aimed at consolidating state control over territories where the reach of the state has historically been weak and contested.