Emergence and Features of the Constitutional Review Bodies in Asia: a Comparative Analysis of Transitional Countries’ Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Total Detention, Charge and Fatality Lists

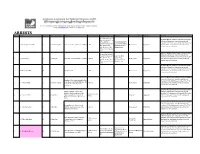

ARRESTS No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark S: 8 of the Export and Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Import Law and S: 25 leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and of the Natural Superintendent Kyi President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Disaster Management Lin of Special Branch, 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F General Aung San State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and law, Penal Code - Dekkhina District regions were also detained. 505(B), S: 67 of the Administrator Telecommunications Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD S: 25 of the Natural leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Disaster Management Superintendent President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s law, Penal Code - Myint Naing, 2 (U) Win Myint M U Tun Kyin President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and 505(B), S: 67 of the Dekkhina District regions were also detained. Telecommunications Administrator Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Union Assembly, the President U Win Myint were detained. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 141 WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 29, 1995 No. 154 Senate (Legislative day of Monday, September 25, 1995) The Senate met at 9 a.m., on the ex- DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE, JUS- Mr. President, I intend to be brief, piration of the recess, and was called to TICE, AND STATE, THE JUDICI- and I note the presence of the Senator order by the President pro tempore ARY, AND RELATED AGENCIES from North Dakota here on the floor. I [Mr. THURMOND]. APPROPRIATIONS ACT, 1996 know that he needs at least 10 minutes The PRESIDENT pro tempore. The of the 30 minutes for this side. I just want to recap the situation as PRAYER clerk will report the pending bill. The assistant legislative clerk read I see this amendment. First of all, Mr. The Chaplain, Dr. Lloyd John as follows: President, the choice is clear here what Ogilvie, offered the following prayer: A bill (H.R. 2076) making appropriations we are talking about. The question is Let us pray: for the Department of Commerce, Justice, whether we will auction this spectrum off, which, according to experts, the Lord of history, God of Abraham and and State, the Judiciary and related agen- value is between $300 and $700 million, Israel, we praise You for answered cies for the fiscal year ending September 30, 1996, and for other purposes. or it will be granted to a very large and prayer for peace in the Middle East very powerful corporation in America manifested in the historic peace treaty The Senate resumed consideration of for considerably less money. -

The Strange Revival of Bicameralism

The Strange Revival of Bicameralism Coakley, J. (2014). The Strange Revival of Bicameralism. Journal of Legislative Studies, 20(4), 542-572. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2014.926168 Published in: Journal of Legislative Studies Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2014 Taylor & Francis. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:01. Oct. 2021 Published in Journal of Legislative Studies , 20 (4) 2014, pp. 542-572; doi: 10.1080/13572334.2014.926168 THE STRANGE REVIVAL OF BICAMERALISM John Coakley School of Politics and International Relations University College Dublin School of Politics, International Studies and Philosophy Queen’s University Belfast [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT The turn of the twenty-first century witnessed a surprising reversal of the long-observed trend towards the disappearance of second chambers in unitary states, with 25 countries— all but one of them unitary—adopting the bicameral system. -

The Ripon Society July, 1965 Vol

THE RIPON NEWSLETTER OF . F . THE RIPON SOCIETY JULY, 1965 VOL. 1, No. 5 The View From Here THE GOLDWATER MOVEMENT RESURFACES: A Ripon Editorial Report This month marks the anniv~ of Barry Union, headed by former Congressman Donald Bruce Goldwater's Convention and his nomination to head of Indiana. Many political observers feel that Gold theRePlJblican ticket of 1964. IIi the ~ ~ that has water has made a serious blunder that will only hurt passed, the Goldwater "conservative" crusade has suf- the "conservative" position. We disagree. fered a devastatin£a~=~ setback, as well as the loss The new orGani%lZtlOn, with (F.oldwater's n41IUI, hIlS of its own party' Dean Burch. When Ohio's real prospects Of huilding a powerful memhershie and Ray Bliss was elected to the Republican Party chair resource hlUe. As Senate R.e~ican Lediler Dirksen manship in January, veteran political correspondents slwewiUl ohser1led,in politics "there is no substitute lor who were on hand in Chicago spoke of ..the end of money.' .Goldwlller wants a "consensus orgilllnZll the Goldwater era" in R~lican politics. Today, lion" for conser1lIll!1les and with the resourcel he com this forecast seems to have been premature. For die manils, he Clltl get it. Alread, there are reports thlll the Goldwater Right is very much alive and dominating the PSA will tap some ofthe est,mated $600,000 still heing political news. The moderate Republicans, who nave withheld from the Pari, hI the Citizens Committee fOr learned little from recent party histo9', are as confused GoldWlller-Mill81' and the Nlllional Tele1lision Com";'" and leaderless today as they were before San Franc::isco. -

Situation Analysis of Myanmar's Region and State Hluttaws

1 Authors This research product would not have been possible without Carl DeFaria the great interest and cooperation of Hluttaw and government representatives in Mon, Mandalay, Shan and Tanintharyi Philipp Annawitt Region and States. We would like express our heartfelt thanks to Daw Tin Ei, Speaker of the Mon State Hluttaw, U Aung Kyaw Research Team Leader Oo, Speaker of the Mandalay Region Hluttaw, U Sai Lone Seng, Aung Myo Min Speaker of the Shan State Hluttaw, and U Khin Maung Aye, Speaker of the Tanintharyi Region Hluttaw, who participated enthusiastically in this project and made themselves, their Researcher and Technical Advisor MPs and staff available for interviews, and who showed great Janelle San ownership throughout the many months of review and consultation on the findings and resulting recommendations. We also wish to thank Chief Ministers U Zaw Myint Maung, Technical Advisor Dr Aye Zan, U Linn Htut, and Dr. Le Le Maw for making Warren Cahill themselves and/or their ministers and cabinet members available for interviews, and their Secretaries of Government who facilitated travel authorizations and set up interviews Assistant Researcher with township officials. T Nang Seng Pang In particular, we would like to thank the eight constituency Research Team Members MPs interviewed for this research who took several days out of their busy schedule to organize and accompany our research Hlaing Yu Aung team on visits to often remote parts of their constituencies Min Lawe and organized the wonderful meetings with ward and village tract administrators, household heads and community Interpreters members that proved so insightful for this research and made our picture of the MP’s role in Region and State governance Dr. -

Thirteenth Annual Report 2001

ACCESS TO SERVICES Office Holders President: The Honourable Don Wing, MLC Telephone: [03] 6233 2322 Facsimile: [03] 6233 4582 Email: [email protected] Deputy President and Chair of Committees: The Honourable Jim Wilkinson, MLC Telephone: [03] 6233 2980 Facsimile: [03] 6231 1849 Email: [email protected] Executive Officers Clerk of the Council: Mr R.J. Scott McKenzie Telephone: [03] 6233 2331 Email: [email protected] Deputy Clerk: Mr David T. Pearce Telephone: [03] 6233 2333 Email: [email protected] Clerk-Assistant and Usher of the Black Rod Miss Wendy M. Peddle Telephone: [03] 6233 2311 Email: [email protected] Second Clerk-Assistant and Clerk of Committees: Mrs Sue E. McLeod Telephone: [03] 6233 6602 Email: [email protected] Enquiries General: Telephone : [03] 6233 2300/3075 Facsimile: [03] 6231 1849 Papers Office: Telephone : [03] 6233 6963/4979 Parliament’s Website: http://www.parliament.tas.gov.au Legislative Council Report 2001-2002 Page 1 Postal Address: Legislative Council, Parliament House, Hobart, Tas 7000 Legislative Council Report 2001-2002 Page 2 PUBLIC AWARENESS The Chamber During the year a variety of groups and individuals are introduced to the Parliament and in particular the Legislative Council through conducted tours. The majority of the groups conducted through the Parliament during the year consisted of secondary and primary school groups. The majority of groups and other visitors who visited the Parliament did so when the Houses were in session giving them a valuable insight into the debating activity that occurs on the floor of both Houses. -

Political Parties Say Govt Limiting Political, Civil Activities at News Report

Eye on the News [email protected] Truthful, Factual and Unbiased Vol:XI Issue No:126 Price: Afs.20 www.afghanistantimes.af www.facebook.com/ afghanistantimeswww.twitter.com/ afghanistantimes SUNDAY . DECEMBER 03. 2017 -Qaws 12, 1396 HS AT Monitoring Desk Regional Studies (CSRS) shows. government has no real will in The survey entitled ‘Peace bringing peace in the country. KABUL: Most Afghan people Stalemate and Solutions’ was The result of the survey shows: believe that an Afghan-led and conducted in six provinces • 83.8% of the respondents Afghan-owned peace process can including Kabul, Herat, Kandahar, said the current war has no winner put an end to the current war Balkh and Kunduz. The results and it can only be stopped by between the government and were released on Saturday at a bringing about peace. Taliban group, a survey conducted meeting in Kabul. A big number of • 67.4% of the respondents by the Center for Strategic and the respondents also have said that said the government has no...P2 Political parties say govt limiting political, civil activities AT News Report KABUL: Some political parties accuse the government of restricting political and civil activities which is against democracy. Meanwhile, a number of parliamentarians call opposition to the Kandahar session illegal, saying that political parties have the right to criticize government. They said that government made efforts to prevent Ata Mohammad Noor from participating in the Kandahar session, a measure that shows the government restricting political activities. Political parties AT News Report current uncertainly, aimed at crisis. “If the nation doesn’t raise National Directorate of Security, say that the government is bringing reforms and overcome voices, challenges will be increased and leadership-member of opposing any political and civil KABUL: A group of politicians, challenges nationwide. -

DASHED HOPES the Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS DASHED HOPES The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar WATCH Dashed Hopes The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar Copyright © 2019 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36970 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org FEBRUARY 2019 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36970 Dashed Hopes The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology ...................................................................................................................... 5 I. Background ..................................................................................................................... 6 II. Section 66(d) -

List of Contents

List of Contents A. Pyidaungsu Hluttaw Pyithu Hlluttaw Election Results 2015, with historical Comparison Amyotha Hluttaw Election Results 2015, with historical Comparison Pyithu Hlluttaw Election Results 2015, with MP Information Amyotha Hluttaw Election Results 2015, with MP Information Political Party Representation in the Pyithu Hluttaw (December 2014) Pyithu Hluttaw Election Results 2015 Political Party Representation in the Amyotha Hluttaw (December 2014) Amyotha Hluttaw Election Results 2015 Pyithu Hluttaw Constituency Boundaries, 2015 Elections Amyotha Hluttaw Constituency Boundaries, 2015 Elections Eligible Voters per Pyithu Hluttaw Constituency, 2015 Elections Eligible Voters per Amyotha Hluttaw Constituency, 2015 Elections Candidates per Pyithu Hluttaw Constituency, 2015 Elections Candidates per Amyotha Hluttaw Constituency, 2015 Elections Turnout in the 2015 Elections Invalid Votes in the 2015 Elections Advance Votes in the 2015 Elections Transferred Votes in the 2015 Elections Areas where elections did not take place in 2010 / 2012 Election Cancellations 2010 – 2015 Sequence of 2015 Election Cancellations 2015 Election Cancellations & Vacant Seats B. State and Region Hluttaws State and Region Hluttaw Election Results 2015 (on Union level) State and Region Hluttaw Election Results 2015, with MP Information Political Party Representation Before Elections 2015, Ayeyarwady Region Hluttaw Election Results 2015, Ayeyarwady Region Hluttaw Political Party Representation Before Elections 2015, Bago Region Hluttaw Election Results 2015, -

A Consideration of Democratic Participation in Switzerland and Britain with Reference to the Management of an Educational Issue at Local Level in Both Countries

A Consideration of Democratic Participation in Switzerland and Britain with Reference to the Management of an Educational Issue at Local Level in both Countries Robert Kenrick JONES A Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy Institute of Education University of London 2007 VOL. I Acknowledgements I wish to record my thanks to the following people for the invaluable help and advice they have provided. To Professor Richard Topf of London Metropolitan University for his endless patience and the academic insights he has shown me, to the staff of the Institute of Education London University and to Dr Ernest Bollinger former Chef de 1’Information of the canton of Geneva, to Yves Flicker, Lecturer in Social Studies in the University of Geneva and finally to my wife for adjusting our life to facilitate this venture. 2 4 ABSTRACT A consideration of democratic participation in Switzerland and Britain with reference to the management of an educational issue at local level in both countries This thesis is concerned with participatory democracy and its effectiveness in action. The aim of the underlying research has been to examine this form of democracy as it is revealed in one country (Switzerland) and within that to focus on a specific canton (Geneva); secondly to compare it with the democratic structure of the United Kingdom and again focusing on a particular region - the County of Buckinghamshire. In each case, at the local level, I have chosen one sensitive issue - education- and considered how far people participated in their own destinies, written from a United Kingdom background. -

Group Research, Inc. Records, 1955-1996 MS# 0525 ©2007 Columbia University Library

Group Research, Inc. Records, 1955-1996 MS# 0525 ©2007 Columbia University Library This document is converted from a legacy finding aid. We provide this Internet-accessible document in the hope that users interested in this collection will find this information useful. At some point in the future, should time and funds permit, this finding aid may be updated. SUMMARY INFORMATION Creator Group Research, Inc. Title and dates Group Research, Inc. Records, 1955-1996 Abstract Founded by Wesley McCune and based in Washington DC until ceasing operations in the mid-1990s, Group Research Inc. collected materials that focus on the right-wing and span four decades. The collection contains correspondence, memos, reports, card files, audio-visual material, printed matter, clippings, etc. Size 215 linear ft. (512 document boxes; Map Case 14/16/05 and flat box #727) Call number MS# 0525 Location Columbia University Butler Library, 6th Floor Rare Book and Manuscript Library 535 West 114th Street Page 1 of 142 Group Research Records Box New York, NY 10027 Language(s) of material English History of Group Research, Inc. A successful journalist for such magazines as Newsweek, Time, Life and Changing Times as well as a staff member of several government agencies and government-related organizations, Wesley McCune founded Group Research Inc. in 1962. Based in Washington DC until ceasing operations in the mid-1990s Group Research Inc. collected materials that focus on the right--wing and span four decades. The resulting Group Research archive includes information about and by right-wing organizations and activists in the form of publications correspondence pamphlets reports newspaper Congressional Record and magazine clippings and other ephemera. -

Election Monitor No.40

Euro-Burma Office 4 to 10 September 2010 Election Monitor ELECTION MONITOR NO. 40 SHAN STATE, PA-O SELF-ADMINISTERED ZONE ELECTORAL SUB-COMMISSIONS MEET A meeting between the Shan State Electoral Sub-commission and the Pa-O Self-Administered Zone Sub- commission was held at the meeting hall of Hopong Township Sub-commission on 27 August. The chairman of Shan State Sub-commission, U Pwint, addressed the meeting and sub-commission members. Township Law Officer, U Maung Maung, and Deputy Director of the Information and Public Relations Department, Daw May May Ni, explained the election laws, rules and the electoral process. U Thet Tun, the chairman of Pa-O Self- Administered Zone Sub-commission, discussed the electoral work this is to be jointly carried out by the Hopong, Hsihseng and Pinlaung Townships. U Than Win, the chairman of Hopong Township Sub-commission, also discussed conducting electoral training courses and issues related to the preparation of sites to be designated as polling stations with sub-commission members.1 ELECTORAL PROCESS COURSES OPENED IN MAUBIN TOWNSHIP On 2 September, a training course on the electoral process organized by the Maubin Township Election Sub- commission in Maubin District, Ayeyawady Region for returning officers, deputy returning officers and members of polling stations was opened at the Aungheit village-tract. Those present included Members of Maubin District Sub-commission Daw Ngwe Khin and U Myo Myint as well as trainees. Township election sub- commission members U Thaung Nyunt, U Htein Lin and U Myint Soe briefed those present on electoral laws and by-laws and gave lectures on the electoral process for returning officers and deputy returning officers.