Leiter on Dworkin and Nonsense Jurisprudence Timothy Stostad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Centrality of Practical Reason: Dworkin and Kant

The centrality of practical reason: Dworkin and Kant In one of his latest books Justice for Hedgehogs (2011) Ronald Dworkin presents a thorough critique of contemporary ethical discourse. Explicitly his arguments mostly seek to undermine the main premises of metaethics, especially, the assumption that it is possible to think and talk about ethics from a neutral Archimedian position and to find its grounding in scientific or metaphysical facts. Moreover, he aims to present his own position as a specific revolution – a position which questions all the ways of approaching ethics that dominate or influence the field of moral philosophy since modern times, namely Descartes. There have been many attempts to criticize, question and evaluate this critique, its accuracy and extent.1 However, much less effort have been made to properly and comprehensively evaluate the constructive and potential side of Dworkin’s position. The main question that his critique of contemporary ethical discourse raises is ‘How should we approach ethical questions and problems?’ or ‘How should we do moral philosophy?’ Such questions are essential for the discourse itself. They should determine not only the shape and methods, but also the future and raison d’etre of ethical theory as such. Dworkin himself takes Hume to be the inspiration for his revolution. According to Dworkin, Hume’s distinction between fact and value gives us a clear guidance as to how we should proceed in ethical discourse. Dworkin develops this distinction as his main argument that ethics is an independent domain of thought. However, my paper argues, that despite Dworkin’s appeal of Hume, his position cannot be seen as Humean and is much more akin to Kant as there are several substantial conformities between their theories and premises. -

"Suggestions for Further Reading." Censorship Moments: Reading Texts in the History of Censorship and Freedom of Expression

"Suggestions for Further Reading." Censorship Moments: Reading Texts in the History of Censorship and Freedom of Expression. Ed. Geoff Kemp. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015. 195–202. Textual Moments in the History of Political Thought. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 26 Sep. 2021. <>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 26 September 2021, 01:37 UTC. Copyright © Geoff Kemp and contributors 2015. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. Suggestions for Further Reading Given the substantial quantity of writing on most of the thinkers and many of the works covered in this volume, the following list is necessarily highly selective. For each work an attempt has been made to include a readily available reliable text in English (sometimes available online), in some cases a scholarly edition, and several works which help to contextualize the principal text and scholarly discussion of it. Plutarch’s Life of Cato Plutarch, ‘Marcus Cato’, in Plutarch’s Lives, accessible at www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/ text?doc=Perseus%3atext%3a2008.01.0013 [accessed 18 May 2014]. Alan E. Astin, Cato the Censor (Oxford: At the Clarendon Press, 1978). Arlene W. Saxonhouse, Free Speech and Athenian Democracy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006). Robin Waterfield, Why Socrates Died: Dispelling the Myths (New York: Norton, 2009). Dana Villa, Socratic Citizenship (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001). Tacitus’s Annals Tacitus, The Annals, translated by A.J. Woodman (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2004). Shadi Bartsch, Actors in the Audience: Theatricality and Doublespeak from Nero to Hadrian (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998). -

The Use of Philosophers by the Supreme Court Neomi Raot

A Backdoor to Policy Making: The Use of Philosophers by the Supreme Court Neomi Raot The Supreme Court's decisions in Vacco v Quill' and Wash- ington v Glucksberg2 held that a state can ban assisted suicide without violating the Due Process or Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. In these high profile cases, six phi- losophers filed an amicus brief ("Philosophers'Brief') that argued for the recognition of a constitutional right to die.3 Although the brief was written by six of the most prominent American philoso- phers-Ronald Dworkin, Thomas Nagel, Robert Nozick, John Rawls, Thomas Scanlon, and Judith Jarvis Thomson-the Court made no mention of the brief in unanimously reaching the oppo- site conclusion.4 In light of the Court's recent failure to engage philosophical arguments, this Comment examines the conditions under which philosophy does and should affect judicial decision making. These questions are relevant in considering the proper role of the Court in controversial political questions and are central to a recent de- bate focusing on whether the law can still be considered an autonomous discipline that relies only on traditional legal sources. Scholars concerned with law and economics and critical legal studies have argued that the law is no longer autonomous, but rather that it does and should draw on many external sources in order to resolve legal disputes. Critics of this view have main- tained that legal reasoning is distinct from other disciplines, and that the law has and should maintain its own methods, conven- tions, and conclusions. This Comment follows the latter group of scholars, and ar- gues that the Court should, as it did in the right-to-die cases, stay clear of philosophy and base its decisions on history, precedent, and a recognition of the limits of judicial authority. -

Critical Guide to Mill's on Liberty

This page intentionally left blank MILL’S ON LIBERTY John Stuart Mill’s essay On Liberty, published in 1859, has had a powerful impact on philosophical and political debates ever since its first appearance. This volume of newly commissioned essays covers the whole range of problems raised in and by the essay, including the concept of liberty, the toleration of diversity, freedom of expression, the value of allowing “experiments in living,” the basis of individual liberty, multiculturalism, and the claims of minority cultural groups. Mill’s views have been fiercely contested, and they are at the center of many contemporary debates. The essays are by leading scholars, who systematically and eloquently explore Mill’s views from various per spectives. The volume will appeal to a wide range of readers including those interested in political philosophy and the history of ideas. c. l. ten is Professor of Philosophy at the National University of Singapore. His publications include Was Mill a Liberal? (2004) and Multiculturalism and the Value of Diversity (2004). cambridge critical guides Volumes published in the series thus far: Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit edited by dean moyar and michael quante Mill’s On Liberty edited by c. l. ten MILL’S On Liberty A Critical Guide edited by C. L. TEN National University of Singapore CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521873567 © Cambridge University Press 2008 This publication is in copyright. -

New Legal Realism at Ten Years and Beyond Bryant Garth

UC Irvine Law Review Volume 6 Article 3 Issue 2 The New Legal Realism at Ten Years 6-2016 Introduction: New Legal Realism at Ten Years and Beyond Bryant Garth Elizabeth Mertz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.uci.edu/ucilr Part of the Law and Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Bryant Garth & Elizabeth Mertz, Introduction: New Legal Realism at Ten Years and Beyond, 6 U.C. Irvine L. Rev. 121 (2016). Available at: https://scholarship.law.uci.edu/ucilr/vol6/iss2/3 This Foreword is brought to you for free and open access by UCI Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UC Irvine Law Review by an authorized editor of UCI Law Scholarly Commons. Garth & Mertz UPDATED 4.14.17 (Do Not Delete) 4/19/2017 9:40 AM Introduction: New Legal Realism at Ten Years and Beyond Bryant Garth* and Elizabeth Mertz** I. Celebrating Ten Years of New Legal Realism ........................................................ 121 II. A Developing Tradition ............................................................................................ 124 III. Current Realist Directions: The Symposium Articles ....................................... 131 Conclusion: Moving Forward ....................................................................................... 134 I. CELEBRATING TEN YEARS OF NEW LEGAL REALISM This symposium commemorates the tenth year that a body of research has formally flown under the banner of New Legal Realism (NLR).1 We are very pleased * Chancellor’s Professor of Law, University of California, Irvine School of Law; American Bar Foundation, Director Emeritus. ** Research Faculty, American Bar Foundation; John and Rylla Bosshard Professor, University of Wisconsin Law School. Many thanks are owed to Frances Tung for her help in overseeing part of the original Tenth Anniversary NLR conference, as well as in putting together some aspects of this Symposium. -

February . 1.1, E X T E N S I 0 N S 0 F R E· M a R

2374 CONGRESSIONAL ~ RECORD-· SENATE February . 1.1, we are hypnotized by' this", -and by overly ,.. It is up- to ..us- who now occupy .om.ce ·· Lt. Gen. Alfred Dodd Starbird, 018961, meticulous: attention-to the question of in the legislative.. and executive branches Army of the United States (brigadier gen of all who 'Of e:tal, U.S. Army). whether or- not the military menace to the Government, ·and have Maj. Gen. William Jonas Ely, 018974, Army us Is inereased or decreased fractionally ficial responsibilities, earnestly to search o! the United States (brigadier general, U.S. by the l)reseoce or absence of certain for an answer to·the problem, and ear .Army). tYPes -or quantities of military forces, nestly and ' honestly apply ourselves in Maj. Gen. Harold Keith Johnson, 019187, it tna.y very well be that we will fail to o.ur respective ways and in keeping with Army of the United States (brigadier gen face up to the basic problem-the fact our obligations to apply policies that eral, U.S. Army) • that international communism has been will meet the problem and bring about a Maj. Gen. Ben Harrell, 019276, Army of is the United States (brigadier general, U.S. established and being maintained in remedy. I know that we can do it. I Arm.y). the Western Hemisphere. believe that we shall do it. I also. believe Maj. Gen. Alden Kingsland Sibley, 018964, The American people, I believe, look that there is no time to ·be lost. Army of the United States (brigadier gen- for a very simple and' fundamental thing Mr. -

2016 Year in Review

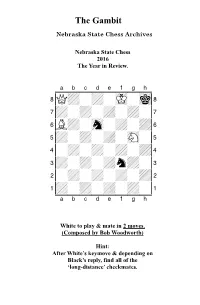

The Gambit Nebraska State Chess Archives Nebraska State Chess 2016 The Year in Review. XABCDEFGHY 8Q+-+-mK-mk( 7+-+-+-+-' 6L+-sn-+-+& 5+-+-+-sN-% 4-+-+-+-+$ 3+-+-+n+-# 2-+-+-+-+" 1+-+-+-+-! xabcdefghy White to play & mate in 2 moves. (Composed by Bob Woodworth) Hint: After White’s keymove & depending on Black’s reply, find all of the ‘long-distance’ checkmates. Gambit Editor- Kent Nelson The Gambit serves as the official publication of the Nebraska State Chess Association and is published by the Lincoln Chess Foundation. Send all games, articles, and editorial materials to: Kent Nelson 4014 “N” St Lincoln, NE 68510 [email protected] NSCA Officers President John Hartmann Treasurer Lucy Ruf Historical Archivist Bob Woodworth Secretary Gnanasekar Arputhaswamy Webmaster Kent Smotherman Regional VPs NSCA Committee Members Vice President-Lincoln- John Linscott Vice President-Omaha- Michael Gooch Vice President (Western) Letter from NSCA President John Hartmann January 2017 Hello friends! Our beloved game finds itself at something of a crossroads here in Nebraska. On the one hand, there is much to look forward to. We have a full calendar of scholastic events coming up this spring and a slew of promising juniors to steal our rating points. We have more and better adult players playing rated chess. If you’re reading this, we probably (finally) have a functional website. And after a precarious few weeks, the Spence Chess Club here in Omaha seems to have found a new home. And yet, there is also cause for concern. It’s not clear that we will be able to have tournaments at UNO in the future. -

Distinguishing Science from Philosophy: a Critical Assessment of Thomas Nagel's Recommendation for Public Education Melissa Lammey

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 Distinguishing Science from Philosophy: A Critical Assessment of Thomas Nagel's Recommendation for Public Education Melissa Lammey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS & SCIENCES DISTINGUISHING SCIENCE FROM PHILOSOPHY: A CRITICAL ASSESSMENT OF THOMAS NAGEL’S RECOMMENDATION FOR PUBLIC EDUCATION By MELISSA LAMMEY A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Philosophy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Melissa Lammey defended this dissertation on February 10, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Michael Ruse Professor Directing Dissertation Sherry Southerland University Representative Justin Leiber Committee Member Piers Rawling Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Warren & Irene Wilson iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is my pleasure to acknowledge the contributions of Michael Ruse to my academic development. Without his direction, this dissertation would not have been possible and I am indebted to him for his patience, persistence, and guidance. I would also like to acknowledge the efforts of Sherry Southerland in helping me to learn more about science and science education and for her guidance throughout this project. In addition, I am grateful to Piers Rawling and Justin Leiber for their service on my committee. I would like to thank Stephen Konscol for his vital and continuing support. -

1 Realism V Equilibrism About Philosophy* Daniel Stoljar, ANU 1

Realism v Equilibrism about Philosophy* Daniel Stoljar, ANU Abstract: According to the realist about philosophy, the goal of philosophy is to come to know the truth about philosophical questions; according to what Helen Beebee calls equilibrism, by contrast, the goal is rather to place one’s commitments in a coherent system. In this paper, I present a critique of equilibrism in the form Beebee defends it, paying particular attention to her suggestion that various meta-philosophical remarks made by David Lewis may be recruited to defend equilibrism. At the end of the paper, I point out that a realist about philosophy may also be a pluralist about philosophical culture, thus undermining one main motivation for equilibrism. 1. Realism about Philosophy What is the goal of philosophy? According to the realist, the goal is to come to know the truth about philosophical questions. Do we have free will? Are morality and rationality objective? Is consciousness a fundamental feature of the world? From a realist point of view, there are truths that answer these questions, and what we are trying to do in philosophy is to come to know these truths. Of course, nobody thinks it’s easy, or at least nobody should. Looking over the history of philosophy, some people (I won’t mention any names) seem to succumb to a kind of triumphalism. Perhaps a bit of logic or physics or psychology, or perhaps just a bit of clear thinking, is all you need to solve once and for all the problems philosophers are interested in. Whether those who apparently hold such views really do is a difficult question. -

Contributors' Notes

Contributors' Notes Frances E. Dolan is Assistant Professor of English at Miami Univer- sity, Ohio. Her essays have appeared or are forthcoming in Medieval and Renaissance Drama, PMLA, and SEL. She is currently completing a book, DangerousFamiliars: PopularAccounts of Domestic Crime in Eng- land, 1550-1700, of which the present essay is a part. Barbara Taback Schneider is a 1990 graduate of Harvard Law School. She is currently an attorney in Portland, Maine, with the firm of Murray, Plumb & Murray. The paper on which her article was based received the Irving Oberman Memorial Award from the Law School for the best es- say by a graduating law student on a current legal topic. In 1990 that topic was legal history. Brian Leiter is a graduate student in philosophy at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where he is writing a dissertation on Nietzche's critique of morality. A graduate of Princeton, he also holds a law degree from the University of Michigan and is a member of the New York Bar. John Martin Fischer received his Ph.D. in philosophy from Cornell University in 1982. He taught for seven years in the philosophy depart- ment at Yale University as an assistant and associate professor. He is currently Professor of Philosophy at the University of California, River- side. He has written on various topics in moral philosophy and meta- physics, especially free will and moral responsibility. Recently, he has published a book jointly edited with Mark Ravizza entitled Ethics: Problems and Principles (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1991). Mark Tushnet, Professor of Law, Georgetown University Law Center, has written on constitutional law and legal history. -

Book Reviews Did Formalism Never Exist?

BROPHY.FINAL.OC (DO NOT DELETE) 12/18/2013 9:48 AM Book Reviews Did Formalism Never Exist? BEYOND THE FORMALIST-REALIST DIVIDE: THE ROLE OF POLITICS IN JUDGING. By Brian Z. Tamanaha. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2010. 252 pages. $24.95. Reviewed by Alfred L. Brophy* In Beyond the Formalist-Realist Divide, Brian Tamanaha seeks to rewrite the story of the differences between the age of formalism and the age of legal realism. In essence, Tamanaha thinks there never was an age of formalism. For he sees legal thought even in the Gilded Age of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—what is commonly known as the age of formalism1—as embracing what he terms “balanced realism.”2 Legal history3 and jurisprudence4 both make important use of that divide, or, to use somewhat less dramatic language, the shift from formalism (known often as classical legal thought) to realism. Moreover, as Tamanaha describes it, recent studies of judicial behavior that model the extent to which judges are formalist—that is, the extent to which they apply the law in some neutral fashion or, conversely, recognize the centrality of politics to * Judge John J. Parker Distinguished Professor of Law, University of North Carolina. I would like to thank Michael Deane, Arthur G. LeFrancois, Brian Leiter, David Rabban, Dana Remus, Stephen Siegel, and William Wiecek for help with this. 1. See, e.g., MORTON J. HORWITZ, THE TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN LAW 1870–1960, at 16–18 (1992) [hereinafter HORWITZ, TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN LAW 1870–1960] (discussing formalism, generally); MORTON J. -

The Queen's Gambit

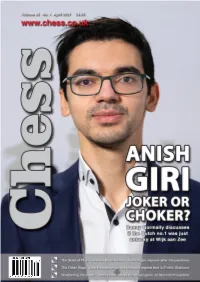

01-01 Cover - April 2021_Layout 1 16/03/2021 13:03 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/03/2021 11:45 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Associate Editor: John Saunders 60 Seconds with...Geert van der Velde.....................................................7 Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington We catch up with the Play Magnus Group’s VP of Content Chess Magazine (ISSN 0964-6221) is published by: A Tale of Two Players.........................................................................................8 Chess & Bridge Ltd, 44 Baker St, London, W1U 7RT Wesley So shone while Carlsen struggled at the Opera Euro Rapid Tel: 020 7486 7015 Anish Giri: Choker or Joker?........................................................................14 Email: [email protected], Website: www.chess.co.uk Danny Gormally discusses if the Dutch no.1 was just unlucky at Wijk Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine How Good is Your Chess?..............................................................................18 Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Daniel King also takes a look at the play of Anish Giri Twitter: @chessandbridge The Other Saga ..................................................................................................22 Subscription Rates: John Henderson very much