Putting the Corporation in Its Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Company Formation Information

Company Formation Information THE UK COMPANY What our Clients say ADVANTAGES OF ADVANTAGES OF USING “Just to confirm receipt of the pack in INCORPORATION YORK PLACE the above and to thank you for your prompt and efficient service; a service Limited liability for members Experts in company formation with which I would have no hesitation in (shareholders) many years experience, and managed using again or recommending.” by Chartered Secretaries Perpetual succession as companies “I can’t thank you enough for all that carry on even though directors/ Articles of association settled you do!” members leave by leading lawyers and guaranteed to be compliant with the “Thanks, that’s excellent news! You The company name is unique and Companies Act 2006 should see the size of the smile on my therefore protected face! I’d been worried that name would State-of-the-art systems for get pulled out from underneath me There is a governing structure set out fast electronic incorporation with somehow, so having it all confirmed in the Articles of Association most companies incorporated in really is very, very good news!” 1–2 days with a guaranteed Share capital can be created with sameday option available “Thank you for your help, your expert varying rights to facilitate investment advice, and for the speed of service. You Multiple share class companies have helped make something that was It is possible to create a floating incorporated electronically proving more complicated than I’d have charge over the company assets liked into something really quite simple. Readymade companies are available Registered UK company costs are Thanks again.” amongst the lowest in the world and A range of products to suit all “All credit to you guys for not charging no audit required if turnover is below requirements and budgets minimum limit for the extra work you did on this. -

Doing Business in the Federal Republic of Germany

Denver Journal of International Law & Policy Volume 3 Number 2 Fall Article 4 May 2020 Doing Business in the Federal Republic of Germany Georg Kutschelis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/djilp Recommended Citation Georg Kutschelis, Doing Business in the Federal Republic of Germany, 3 Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y 197 (1973). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Denver Sturm College of Law at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Journal of International Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],dig- [email protected]. DOING BUSINESS IN THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY* GEORG KUTSCHELIS** I. INTRODUCTION II. PRELIMINARY FORMALITIES A. Residence permit (Aufenthaltserlaubnis) B. Labor permit (Arbeitserlaubnis) C. Registration of business (Gewerbeanmeldung) D. Registration of foreign corporate bodies III. LEGAL ORGANIZATION OF A BUSINESS A. Statutory background B. Some peculiarities of German commercial law 1. Kinds of merchants 2. Commercial register 3. Commercial name (Firma) 4. Commercial agency C. Criteria of companies 1. Capacity to hold legal rights (Rechtsfaehigkeit) 2. The dichotomy of company and association 3. Internal and external companies 4. Person-companies and capital-companies 5. Ownership of company assets D. Kinds of Companies 1. Private law company (Gesellschaft buergerlichen- Rechts) 2. Partnership (Offene Handelsgesellschaft) 3. Limited partnership (Kommanditgesellschaft) 4. Silent partnership (Stille Gesellschaft) 5. Stock corporation (Aktiengesellschaft) 6. Partnership limited by shares (Kommanditgesellschaft auf Aktien) 7. Limited liability company (Gesellschaft mit besch- raenkterHaftung) 8. Limited liability company and partner (GmbH & Co KG) 9. -

Company Formation in Argentina

COMPANY FORMATION IN ARGENTINA MAIN FORMS OF COMPANY/BUSINESS IN ARGENTINA According to the law there are six types of companies that, at the moment of setting up a business in Argentina, can be established in the country: • Sociedad Anónima (SA), which is tantamount of the British private companies limited by shares. • Sociedad de Responsabilidad Limitada (SRL), is a private company limited by guarantee. It limits the liability of its members up to their capital contribution in the company. The equity is divided into equal stakes (can’t be called “shares”), each one of which represents a percentage of the company and that can’t be traded on the stock exchange. Their bylaws are regulated by law N° 19550[15] and the commercial partnership is limited to a maximum of 50 partners. • Sociedad en Comandita Simple (SCS), which are partnerships limited by guarantee. A limited partnership (LP) is a form of partnership similar to a general partnership, except that where a general partnership must have at least two general partners (GPs), a limited partnership must have at least one GP and at least one limited partner. • Sociedad en Comandita por Acciones (SCA), partnerships limited by shares. • Sociedad en Nombre Colectivo (SNC), in which all the members share risks and capitals on unlimited basis. • Sociedad de Capital e Industria (SCeI) • Sociedad del Estado (SE), is a legal entity that undertakes commercial activities on behalf of an owner government. • Sociedad de Garantía Recíproca (SGR) • Sociedad Cooperativa (SC), free associations of members with a common social, economic and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly-owned and democratically-controlled enterprise (cooperative). -

Doing Business in Germany 2015

Doing Business in Germany 2015 IMPORTANT DISCLAIMER: This book is not intended to be a comprehensive exposition of all potential issues arising in the context of doing business in Germany, nor of the laws relating to such issues. It is not offered as advice on any particular matter and should not be taken as such. Baker & McKenzie, the editors and the contributing authors disclaim all liability to any person in respect of anything done wholly or partly in reliance upon the whole or part of this book. Before any action is taken or decision not to act is made, specific legal advice should be taken in light of the relevant circumstances and no reliance should be placed on the statements made or documents reproduced in this book. This publication is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study or research permitted under applicable copyright legislation, no part may be reproduced or transmitted by any process or means without the prior permission of the editors. Doing Business in Germany Contributors Christian Atzler Michael Bartosch Christoph Becker Claudia Beuter-Brinkmann Christian Brodersen André Buchholtz Vanessa Dersch Ulrich Ellinghaus Silke Fritz Wolfgang Fritzemeyer Joachim Fröhlich Marc Gabriel Thomas Gilles Tobias Gräbener Heiko Haller Caroline Heinickel Christian Horstkotte Philipp Jost Martin Kaiser Benjamin Koch Hagen Köckeritz Lara Link Nicole Looks Holger Lutz Ghazale Mandegarian Jochen Meyer-Burow Julia Pfeil Christian Port Christian Reichel Jörg Risse Juliane Sassmann Matthias Scholz Oliver Socher -

February . 1.1, E X T E N S I 0 N S 0 F R E· M a R

2374 CONGRESSIONAL ~ RECORD-· SENATE February . 1.1, we are hypnotized by' this", -and by overly ,.. It is up- to ..us- who now occupy .om.ce ·· Lt. Gen. Alfred Dodd Starbird, 018961, meticulous: attention-to the question of in the legislative.. and executive branches Army of the United States (brigadier gen of all who 'Of e:tal, U.S. Army). whether or- not the military menace to the Government, ·and have Maj. Gen. William Jonas Ely, 018974, Army us Is inereased or decreased fractionally ficial responsibilities, earnestly to search o! the United States (brigadier general, U.S. by the l)reseoce or absence of certain for an answer to·the problem, and ear .Army). tYPes -or quantities of military forces, nestly and ' honestly apply ourselves in Maj. Gen. Harold Keith Johnson, 019187, it tna.y very well be that we will fail to o.ur respective ways and in keeping with Army of the United States (brigadier gen face up to the basic problem-the fact our obligations to apply policies that eral, U.S. Army) • that international communism has been will meet the problem and bring about a Maj. Gen. Ben Harrell, 019276, Army of is the United States (brigadier general, U.S. established and being maintained in remedy. I know that we can do it. I Arm.y). the Western Hemisphere. believe that we shall do it. I also. believe Maj. Gen. Alden Kingsland Sibley, 018964, The American people, I believe, look that there is no time to ·be lost. Army of the United States (brigadier gen- for a very simple and' fundamental thing Mr. -

2016 Year in Review

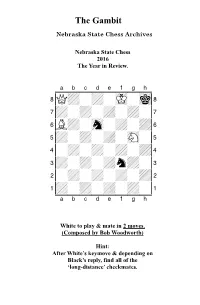

The Gambit Nebraska State Chess Archives Nebraska State Chess 2016 The Year in Review. XABCDEFGHY 8Q+-+-mK-mk( 7+-+-+-+-' 6L+-sn-+-+& 5+-+-+-sN-% 4-+-+-+-+$ 3+-+-+n+-# 2-+-+-+-+" 1+-+-+-+-! xabcdefghy White to play & mate in 2 moves. (Composed by Bob Woodworth) Hint: After White’s keymove & depending on Black’s reply, find all of the ‘long-distance’ checkmates. Gambit Editor- Kent Nelson The Gambit serves as the official publication of the Nebraska State Chess Association and is published by the Lincoln Chess Foundation. Send all games, articles, and editorial materials to: Kent Nelson 4014 “N” St Lincoln, NE 68510 [email protected] NSCA Officers President John Hartmann Treasurer Lucy Ruf Historical Archivist Bob Woodworth Secretary Gnanasekar Arputhaswamy Webmaster Kent Smotherman Regional VPs NSCA Committee Members Vice President-Lincoln- John Linscott Vice President-Omaha- Michael Gooch Vice President (Western) Letter from NSCA President John Hartmann January 2017 Hello friends! Our beloved game finds itself at something of a crossroads here in Nebraska. On the one hand, there is much to look forward to. We have a full calendar of scholastic events coming up this spring and a slew of promising juniors to steal our rating points. We have more and better adult players playing rated chess. If you’re reading this, we probably (finally) have a functional website. And after a precarious few weeks, the Spence Chess Club here in Omaha seems to have found a new home. And yet, there is also cause for concern. It’s not clear that we will be able to have tournaments at UNO in the future. -

Comparative Company Law

Comparative company law 26th of September 2017 – 3rd of October 2017 Prof. Jochen BAUERREIS Attorney in France and Germany Certified specialist in international and EU law Certified specialist in arbitration law ABCI ALISTER Strasbourg (France) • Kehl (Germany) Plan • General view of comparative company law (A.) • Practical aspects of setting up a subsidiary in France and Germany (B.) © Prof. Jochen BAUERREIS - Avocat & Rechtsanwalt 2 A. General view of comparative company law • Classification of companies (I.) • Setting up a company with share capital (II.) • Management bodies (III.) • Transfer of shares (IV.) • Taxation (V.) • General tendencies in company law (VI.) © Prof. Jochen BAUERREIS - Avocat & Rechtsanwalt 3 I. Classification of companies • General classification – Partnerships • Typically unlimited liability of the partners • Importance of the partners – The companies with share capital • Shares can be traded more or less freely • Typically restriction of the associate’s liability – Hybrid forms © Prof. Jochen BAUERREIS - Avocat & Rechtsanwalt 4 I. Classification of companies • Partnerships – « Civil partnership » • France: Société civile • Netherlands: Maatschap • Germany: Gesellschaft bürgerlichen Rechts • Austria: Gesellschaft nach bürgerlichem Recht (GesnbR) • Italy: Società simplice © Prof. Jochen BAUERREIS - Avocat & Rechtsanwalt 5 I. Classification of companies • Partnerships – « General partnership » • France: Société en nom collectif • UK: General partnership (but without legal personality!) • USA: General partnership -

SWEDEN Company Formation Fact Sheet

DISCLAIMER: The contents of this text do not constitute legal advice and are not meant to be complete or exhaustive. Although Warwick Legal Network tries to ensure the information is accurate and up-to-date, all users should seek legal advice before taking or refraining from taking any action. Neither Warwick Legal Network nor its members are liable or accept liability for any loss which may arise from possible errors in the text or from the reliance on information contained in this text. Company formation Fact Sheet – Sweden (per November 2012) Types of company The main form of company with limited liability is; Limited company (sw: Aktiebolag). The limited company may be private or public. There are other forms of business enterprises, such as Trading Partnership (sw: handelsbolag), Limited partnership (sw: kommanditoblag) and Economic Association (sw: ekonomisk förening), but only the Limited Company will be described in this text. Formation Memorandum of association including, among others, requirements - the articles of association, and - certain info regarding the members of the board of directors (one of the first tasks for the board is to prepare the share register), and (if applicable) auditor, deputy members etcetera. Bank certificate, containing information on the amount paid for the shares (special rules apply for certain situations, e.g. if payment of the share capital is made by contribution in kind); and Application for registration Shareholders and The share capital must be, capital minimum 50.000 Swedish kronor for private limited companies, and minimum 500.000 Swedish kronor for public limited companies. Duration of procedure Usually about 2 weeks (from the arrival of the application, at the Swedish Companies Registration Office). -

Corporate Governance Kodex

Declaration on the German Corporate Governance Code for 2015 The Management Board of Henkel Management AG as the personally liable partner (general partner), the Shareholders’ Committee and the Supervisory Board of Henkel AG & Co. KGaA (“the Corporation”) declare, pursuant to Art. 161 German Stock Corporation Act (AktG), that notwithstanding the specific regulations governing companies with the legal form of a German partnership limited by shares (“KGaA”) and to the pertinent provisions of its articles of association (“bylaws”) as indicated below, the Corporation has complied with the recommendations (“shall” clauses) of the German Corporate Governance Code (“Code”) as amended on May 13, 2013, since the last declaration of conformity of February 2014, and presently complies with and will comply in future with the recommendations of the Code as amended on June 24, 2014, subject to certain exceptions indicated below. Modifications due to the legal form of a KGaA and its basic features as laid down in the bylaws • The Corporation is a “Kommanditgesellschaft auf Aktien” (“KGaA”). The tasks and duties of an executive board in a German joint stock corporation (“AG”) are assigned to the personally liable partner(s) of a KGaA. The sole personally liable partner of the Corporation is Henkel Management AG, the Management Board of which is thus responsible for managing the business activities of the Corporation. The Corporation is the sole shareholder of Henkel Management AG. • The shareholders’ committee (“Shareholders’ Committee”) established in accordance with the Corporation’s bylaws acts in place of the Annual General Meeting, its primary duties being to engage in the management of the Corporation’s affairs and to appoint and dismiss personally liable partners; it holds representative authority and power of management allowing it to preside over the legal relationships between the Corporation and Henkel Management AG as the latter’s personally liable partner. -

Experience the Future of Law, Today Reflections on the Legal Form

Experience the future of law, today | Table of Contents Experience the future of law, today Reflections on the legal form Strengthening the equity base through third-party participation while at the same time securing control by the previous owners 00 Experience the future of law, today | Table of Contents Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 Initial situation: Interest in securing control of the company despite the need for equity 2 The partnership limited by shares (Kommanditgesellschaft auf Aktien) as a solution 3 What is the KGaA? 3 What makes the KGaA so unique? 3 Summary 4 01 Experience the future of law, today | Reflections on the legal form Reflections on the legal form Strengthening the equity base of through third- party participation while at the same time securing control by the previous owners Initial situation: Interest in securing control of the company despite the need for equity The current crisis is eating away at the equity capital of numerous German companies. Many of them will in the medium term need additional financial resources, whether to replace state-backed loans from KfW or other state loans and thus restore their ability to pay dividends, to finance investments or simply to strengthen their equity base again. Also, it is conceivable, that acquisitions shall be made without impairing liquidity and that in view of the current slump in share prices other companies shall be taken over - because the opportunity is favorable or circumstances require it (rounding off the portfolio, acquisition of digital competence, securing and making the supply chain more flexible, insourcing, etc.). -

Company Formation Instruction Form

COMPANY FORMATION INSTRUCTION FORM Please complete all sections. COMPANY TYPE Same Day Service* (please also state the company type) Private Limited Company Limited Liability Partnership Company Type Limited by Guarantee Limited by Guarantee Exempt Under Section 60 Flat / Estate Management Company (special objects) Public Limited Company *For the Same Day Service, all completed details including any necessary supporting data must be sent to us by 2:30pm. This will ensure all data is submitted before Companies House’s deadline of 3pm. Companies are processed before close of business of the same day. Items marked N/A are currently unavailable. We constantly strive to improve our portfolio and it is always a good idea to ensure you have the very latest version of our instruction form. COMPANY DETAILS Company Name SIC Code SIC (Standard Industry Classification). If not provided by you, we will use code: (82990 - Other business support service activities not elsewhere classified) Registered Office Address APPOINTMENT Please complete all personal names in full. Do not use initials and please remember to check that the names match the ID provided. For multiple appointments please copy the Appointments table below adding it to a new page and please remember to complete all relevant sections. APPOINTMENT Appointment Type (tick all that apply) Director / Member (LLP’s) Secretary Subscriber / Shareholder PSC CORPORATE BODY / COMPANY APPOINTMENT (if applicable) Please complete this section if the appointment is a corporate body / company. Include -

Declaration on Corporate Governance

Declaration on Corporate Governance The actions of the executive and supervisory bodies of CompuGroup Medical SE & Co. KGaA (hereinafter also re- ferred to as “CompuGroup Medical” or the “Company” and together with its affiliates the “CompuGroup Medical Group”) are governed by the principles of responsible and good corporate governance. In the following, please find the report of the Managing Directors of the Company’s General Partner, CompuGroup Medical Management SE, and the Supervisory Board of CompuGroup Medical on corporate governance in accordance with principle 22 of the German Corporate Governance Code (Code) and in accordance with sections 289f, 315d German Commercial Code (HGB). 1. Statement Pursuant to Section 161 AktG [Aktiengesetz – German Public Companies Act] (Statement of Compliance) DECLARATION BY THE GENERAL PARTNER AND BY THE SUPERVISORY BOARD OF COMPUGROUP MEDICAL SE & CO. KGAA ON THE RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE GOVERNMENT COMMISSION ON THE GERMAN CORPORATE GOVERNANCE CODE (REGIERUNGSKOMMISSION DEUTSCHER CORPORATE GOVERNANCE KODEX) PURSUANT TO SECTION 161 GERMAN STOCK CORPORATION ACT (AKTG) I. Preamble The Management Board and the Supervisory Board of CompuGroup Medical SE last issued a Declaration of Compliance pursuant to Section 161 (1) German Stock Corporation Act (AktG) on January 23, 2020. The Management Board and Supervisory Board of CompuGroup Medical SE amended this Declaration of Com- pliance on February 12, 2020. Based on the resolution of the Annual General Meeting of CompuGroup Medical SE of May 13, 2020, Com- puGroup Medical SE was converted by way of a change of legal form in accordance with the provisions of the German Transformation Act (Sections 190 et seq., 226 et seq., 238 et seq.