American Journal of Play, Volume 4, Number 3 Book Review 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February . 1.1, E X T E N S I 0 N S 0 F R E· M a R

2374 CONGRESSIONAL ~ RECORD-· SENATE February . 1.1, we are hypnotized by' this", -and by overly ,.. It is up- to ..us- who now occupy .om.ce ·· Lt. Gen. Alfred Dodd Starbird, 018961, meticulous: attention-to the question of in the legislative.. and executive branches Army of the United States (brigadier gen of all who 'Of e:tal, U.S. Army). whether or- not the military menace to the Government, ·and have Maj. Gen. William Jonas Ely, 018974, Army us Is inereased or decreased fractionally ficial responsibilities, earnestly to search o! the United States (brigadier general, U.S. by the l)reseoce or absence of certain for an answer to·the problem, and ear .Army). tYPes -or quantities of military forces, nestly and ' honestly apply ourselves in Maj. Gen. Harold Keith Johnson, 019187, it tna.y very well be that we will fail to o.ur respective ways and in keeping with Army of the United States (brigadier gen face up to the basic problem-the fact our obligations to apply policies that eral, U.S. Army) • that international communism has been will meet the problem and bring about a Maj. Gen. Ben Harrell, 019276, Army of is the United States (brigadier general, U.S. established and being maintained in remedy. I know that we can do it. I Arm.y). the Western Hemisphere. believe that we shall do it. I also. believe Maj. Gen. Alden Kingsland Sibley, 018964, The American people, I believe, look that there is no time to ·be lost. Army of the United States (brigadier gen- for a very simple and' fundamental thing Mr. -

2016 Year in Review

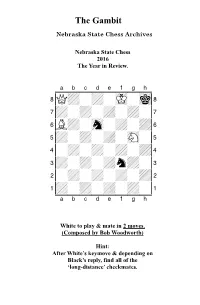

The Gambit Nebraska State Chess Archives Nebraska State Chess 2016 The Year in Review. XABCDEFGHY 8Q+-+-mK-mk( 7+-+-+-+-' 6L+-sn-+-+& 5+-+-+-sN-% 4-+-+-+-+$ 3+-+-+n+-# 2-+-+-+-+" 1+-+-+-+-! xabcdefghy White to play & mate in 2 moves. (Composed by Bob Woodworth) Hint: After White’s keymove & depending on Black’s reply, find all of the ‘long-distance’ checkmates. Gambit Editor- Kent Nelson The Gambit serves as the official publication of the Nebraska State Chess Association and is published by the Lincoln Chess Foundation. Send all games, articles, and editorial materials to: Kent Nelson 4014 “N” St Lincoln, NE 68510 [email protected] NSCA Officers President John Hartmann Treasurer Lucy Ruf Historical Archivist Bob Woodworth Secretary Gnanasekar Arputhaswamy Webmaster Kent Smotherman Regional VPs NSCA Committee Members Vice President-Lincoln- John Linscott Vice President-Omaha- Michael Gooch Vice President (Western) Letter from NSCA President John Hartmann January 2017 Hello friends! Our beloved game finds itself at something of a crossroads here in Nebraska. On the one hand, there is much to look forward to. We have a full calendar of scholastic events coming up this spring and a slew of promising juniors to steal our rating points. We have more and better adult players playing rated chess. If you’re reading this, we probably (finally) have a functional website. And after a precarious few weeks, the Spence Chess Club here in Omaha seems to have found a new home. And yet, there is also cause for concern. It’s not clear that we will be able to have tournaments at UNO in the future. -

The Queen's Gambit

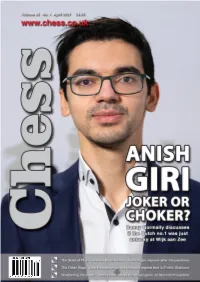

01-01 Cover - April 2021_Layout 1 16/03/2021 13:03 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/03/2021 11:45 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Associate Editor: John Saunders 60 Seconds with...Geert van der Velde.....................................................7 Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington We catch up with the Play Magnus Group’s VP of Content Chess Magazine (ISSN 0964-6221) is published by: A Tale of Two Players.........................................................................................8 Chess & Bridge Ltd, 44 Baker St, London, W1U 7RT Wesley So shone while Carlsen struggled at the Opera Euro Rapid Tel: 020 7486 7015 Anish Giri: Choker or Joker?........................................................................14 Email: [email protected], Website: www.chess.co.uk Danny Gormally discusses if the Dutch no.1 was just unlucky at Wijk Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine How Good is Your Chess?..............................................................................18 Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Daniel King also takes a look at the play of Anish Giri Twitter: @chessandbridge The Other Saga ..................................................................................................22 Subscription Rates: John Henderson very much -

Putting the Corporation in Its Place

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES PUTTING THE CORPORATION IN ITS PLACE Timothy Guinnane Ron Harris Naomi R. Lamoreaux Jean-Laurent Rosenthal Working Paper 13109 http://www.nber.org/papers/w13109 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 May 2007 We thank Svetlana Alkayeva, Ofira Alon, Juan-Francisco Aveleyra, Christopher Cook, Sarah Cullem, Olga Frishman, Theresa Gutberlet, Adam Hofri, Alena Laptiovna, Maria Polyakova, Itai Rabinowitz, Olga Sedjakina, Sarah Shen, Yvonne Taylor, and Eyal Yaacoby for their excellent research assistance. We are grateful for the financial support of the McMillan International Studies Center and the Millstein Center for Corporate Governance and Performance at Yale University, the International Institute and the Dean of Social Science at UCLA, the UCLA Academic Senate, and the Israel Science Foundation. For comments and suggestions we thank Gary Herrigel, Leslie Hannah, Henry Hansmann, Eric Hilt, Timur Kuran, Jonathan Macey, Roberta Romano, Otto Scherner, Kenneth Sokoloff, Jochen Streb, and two anonymous referees, as well as participants in the 2006 SITE Conference on "Risk, Contracts and Organizations," the XIVth World Economic History Congress in Helsinki, the Paris School of Economics Conference on "Not Just Firms: History, Law, and Economics," and seminars at the Harvard Business School, Haifa University Law School, Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods, Bonn, Paris School of Economics, Rheinisch-Westfälisches Institute für Wirtschaftsforschung, Tel Aviv University Law School, University of British Columbia, University of Mannheim, UCLA's Anderson School and International Institute, and Yale Law School. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. -

Fischer Notches Another

FISCHER NOTCHES ANOTHER * (See p. 235) I >:;: UNITED STATES Volume XVJ1l Numher 10 Oclober, 1963 EDITOR: J . F. Reinhardt - U. S. Championship Starts Dec. 15 The 1963-64 United States Championship will be played in New York City from CHESS FEDERATION Sunday, December 15 through ThUt'sday, January 2. As last year, the tournament l' ite will be the Henry Hudson Hotel, 353 W. 57th St. Sunday rounds will be played at 2 p.m.; weekday rounds at 7 p.m.; Saturday rounds at 7:30 p.m. PRESIDENT As we go to press, Bobby Fischer has announced that he wilt defend his title. Major Edmund B. Edmondson, Jr. Others who have accepted invitations to play are Samuel Reshevsky, Donald Byrne, Rohert Byrne, Larry Evans, Pal Benko, and Dr. Anthony Saidy. VICE·PRESIDENT Unfortunately, U. S. Open Champion William L.ombardy will again be unable to David Hoffmann pluy in the event because of his studies. REGIONAL VICE·PRESIDENTS Further details of the U. S. Championsbip...-.including the complete schedule NEW ENGLAND Ell Bourdon will appear in our next issue. Jam.es Burgess Stanley King EASTERN Open Crosstable In Next Issue MID·ATLANTIC Fred Towruend Since we wanted to get the full minutes of the Chicago Business Meetings on George Thomas record as soon as possible, and since this iss ue contains an extra Rating Supplement, William S. Byland we have had to defer running the full crosstable of the record·breaking U. S. Open SOUTHERN Dr. Stuart KOhlln IIntil our November issue. We're sorry for the delay but- even though this is a 32- Jerry Sullivan Dr. -

A Beginner's Guide to Coaching Scholastic Chess

A Beginner’s Guide To Coaching Scholastic Chess by Ralph E. Bowman Copyright © 2006 Foreword I started playing tournament Chess in 1962. I became an educator and began coaching Scholastic Chess in 1970. I became a tournament director and organizer in 1982. In 1987 I was appointed to the USCF Scholastic Committee and have served each year since, for seven of those years I served as chairperson or co-chairperson. With that experience I have had many beginning coaches/parents approach me with questions about coaching this wonderful game. What is contained in this book is a compilation of the answers to those questions. This book is designed with three types of persons in mind: 1) a teacher who has been asked to sponsor a Chess team, 2) parents who want to start a team at the school for their child and his/her friends, and 3) a Chess player who wants to help a local school but has no experience in either Scholastic Chess or working with schools. Much of the book is composed of handouts I have given to students and coaches over the years. I have coached over 600 Chess players who joined the team knowing only the basics. The purpose of this book is to help you to coach that type of beginning player. What is contained herein is a summary of how I run my practices and what I do with beginning players to help them enjoy Chess. This information is not intended as the one and only method of coaching. In all of my college education classes there was only one thing that I learned that I have actually been able to use in each of those years of teaching. -

Glossary of Chess

Glossary of chess See also: Glossary of chess problems, Index of chess • X articles and Outline of chess • This page explains commonly used terms in chess in al- • Z phabetical order. Some of these have their own pages, • References like fork and pin. For a list of unorthodox chess pieces, see Fairy chess piece; for a list of terms specific to chess problems, see Glossary of chess problems; for a list of chess-related games, see Chess variants. 1 A Contents : absolute pin A pin against the king is called absolute since the pinned piece cannot legally move (as mov- ing it would expose the king to check). Cf. relative • A pin. • B active 1. Describes a piece that controls a number of • C squares, or a piece that has a number of squares available for its next move. • D 2. An “active defense” is a defense employing threat(s) • E or counterattack(s). Antonym: passive. • F • G • H • I • J • K • L • M • N • O • P Envelope used for the adjournment of a match game Efim Geller • Q vs. Bent Larsen, Copenhagen 1966 • R adjournment Suspension of a chess game with the in- • S tention to finish it later. It was once very common in high-level competition, often occurring soon af- • T ter the first time control, but the practice has been • U abandoned due to the advent of computer analysis. See sealed move. • V adjudication Decision by a strong chess player (the ad- • W judicator) on the outcome of an unfinished game. 1 2 2 B This practice is now uncommon in over-the-board are often pawn moves; since pawns cannot move events, but does happen in online chess when one backwards to return to squares they have left, their player refuses to continue after an adjournment. -

The Complete Chess Swindler

David Smerdon The Complete Chess Swindler How to Save Points from Lost Positions New In Chess 2020 Contents Explanation of symbols . 6 Acknowledgements . 7 Introduction . 9 Part I What is a swindle? . 17 Chapter 1 When to enter ‘Swindle Mode’ . 30 Part II The Psychology of Swindles . 35 Chapter 2 Impatience . 38 Chapter 3 Hubris . 42 Chapter 4 Fear . 45 Chapter 5 Kontrollzwang . 50 Chapter 6 The Swindler’s Mind . 57 Chapter 7 Grit . 58 Chapter 8 Optimism . 62 Chapter 9 Training Your Mind . 68 Part III The Swindler’s Toolbox . 79 Chapter 10 Trojan Horse . 80 Chapter 11 Decoy Trap . 86 Chapter 12 Berserk Attack . 92 Chapter 13 Window-Ledging . 100 Chapter 14 Play the Player . 108 Part IV Core Skills . 121 Chapter 15 Endgames . 123 Chapter 16 Fortresses . .144 Chapter 17 Stalemate . 160 Chapter 18 Perpetual Check . 168 Chapter 19 Creativity . 183 Chapter 20 Gamesmanship . 195 Part V Swindles in Practice . 207 Chapter 21 Master Swindles . 208 Chapter 22 Amateur Swindles . 254 Chapter 23 My Favourite Swindle . 273 5 The Complete Chess Swindler Part VI Exercises . 277 Test 1 . 278 Test 2 . 289 Test 3 . 299 Solutions to exercises . 309 Epilogue . 349 Index of names . 355 Bibliography . 361 Explanation of symbols The chessboard with its coordinates: 8 TsLdMlSt 7 jJjJjJjJ 6 ._._._._ 5 _._._._. 4 ._._._._ 䩲 White stands slightly better 3 _._._._. 䩱 Black stands slightly better 2 IiIiIiIi White stands better 1 rNbQkBnR Black stands better a b c d e f g h White has a decisive advantage Black has a decisive advantage q White to move balanced position n Black to move ! good move ♔ King !! excellent move ♕ Queen ? bad move ♖ Rook ?? blunder ♗ Bishop !? interesting move ♘ Knight ?! dubious move 6 Introduction Chess is in the last resort a battle of wits, not an exercise in mathematics. -

Online • Thomas E

The official publication of the Texas Chess Association Volume 62, Number 1 Oct-Nov-Dec 2020 $4 86th Annual Southwest Open! Above: 2020 Denker Tournament of High School Champions Table of Contents Message from the Texas Chess Association President ............................................................. 4 TCA Treasurer’s Report ........................................................................................................... 6 Best Lessons of a Chess Coach: Extended Edition by WIM Alexey Root .................................... 7 From the Ivy League to Alcatraz by NM Christopher Toolin ..................................................... 9 TCA Membership Report ....................................................................................................... 13 Chess in the Time of Coronavirus by Robert Myers ................................................................ 14 2020 Denker Tournament of High School Champions by Ambica Yellamraju .......................... 17 2020 Ruth Haring National Girls Tournament of Champions by Aparna Yellamraju ................ 18 Tactics Time! .................................................................................................................. 20 2020 Fort Worth City Championship by Louis Reed ................................................................ 21 86th Annual Southwest Open ................................................................................................ 25 Texas Chess Association A 501(c)(3) educational nonprofit corporation dedicated -

Leiter on Dworkin and Nonsense Jurisprudence Timothy Stostad

North Carolina Central Law Review Volume 35 Article 5 Number 2 Volume 35, Number 2 4-1-2013 A Swindle with Big Words and Virtues: Leiter on Dworkin and Nonsense Jurisprudence Timothy Stostad Follow this and additional works at: https://archives.law.nccu.edu/ncclr Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, and the Public Law and Legal Theory Commons Recommended Citation Stostad, Timothy (2013) "A Swindle with Big Words and Virtues: Leiter on Dworkin and Nonsense Jurisprudence," North Carolina Central Law Review: Vol. 35 : No. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://archives.law.nccu.edu/ncclr/vol35/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by History and Scholarship Digital Archives. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Central Law Review by an authorized editor of History and Scholarship Digital Archives. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stostad: A Swindle with Big Words and Virtues: Leiter on Dworkin and Nonse A SWINDLE WITH BIG WORDS AND VIRTUES?: LEITER ON DWORKIN AND "NONSENSE JURISPRUDENCE" TIMOTHY STOSTAD* ABSTRACT: In a recent essay, Professor Brian Leiter argues that the jurisprudence of Professor Ronald Dworkin, t which Leiter calls "Moralist"jurispru- dence, is neither "relevant [nor] illuminating when it comes to law and adjudication." Exponents of such jurisprudence, Leiter argues, credu- lously attend to the articulated doctrinal rationalesoffered by judges as grounds for their decisions. "Realists," by contrast, recognize that cer- tain nonlegal factors better predict patterns of judicial decision making than do doctrinal rationales. According to Leiter, it follows from the fact that nonlegal factors predict and presumably influence judicial de- cisions, that attention to judges' stated rationales is largely a mistake. -

Flashing the Truth on the Marconi Wireless Swindle

ROTTEN TO THE CORE (Continu .J} Marconi Wireless Stocks Based On Stolen Property ED STATES OFFICIALS and the LORD CHIEF JUSTICE OF ENGLAND CO-CONSPIRATORS IN A FRAUDULENT TRANSACTION. 11icity Campaign Twenty Pages Part Five PUBLISHED BY J. HUGH BAUERLEIN. DENVER , COLO. Ba$ed on Facts -- ~============================================= -. ' .r EARL READING THE LORD CHIEF JUSTICE OF EN<SLAND. THE STAR CONSPIRATOR OF THE MARCONI CLIQUE INTRIGUE. THE DIRTIEST s~7LE ON REC{)RD J • • 2 MARCONI WIRELESS SWINDLE EXPOSED Earl Reading The Lord Chief Justice of England Heralded by His Nationality as the Greatest Jew in the World. Some ) ear:< ago, ther•• was a lillie bnr oC je,vish DENIED THAT HE WAS INTERESTED nallumtllt) braudccl wit11 the IH,nonthle name or Hu Hufu;;-uow th" Lnr<l C'hi••l' .)UHtice uf illngland, Cus J)u.nie.l lS(U.Il'R, tt•hu at the age or R~\~enu~en yc::u·~~ lll<t' all ''g·o<Hl'' men, lHld to fa e au UllJIIeasanL pre •lesired to bel·ume n sailot·, to travel 011 the might)· llicanH•nt. lit>on being duly sworn an<! e"aminP "'"ean to see the glo>·inu,: worl<1. lie shiJIJJE'L1 on lt uucl~r n<lth 11y Lhe Belect ('ornmi\lee of the Parll Hcottish l'rafl-"'The Blair Athol''-trading to Rto mcnl, slated thal lw neYer bad any tl<.:alings in eit with <'nal. His duties were to keep the brasr;:-worJ;o the ~lan.:oni 01~ auy \\ i1·eh•sR ent~rprh;e- :5l'e Q. 5, elean. but little Hufus got discouraged. -

Chess Mag - 21 6 10 15/04/2020 14:55 Page 3

01-01 Cover_Layout 1 14/04/2020 13:10 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 15/04/2020 14:55 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Associate Editor: John Saunders Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington 60 Seconds with... Gary Lane........................................................................7 Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine Living in Sydney, Gary has to rise at 2am to follow Torquay United Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Website: www.chess.co.uk Candidates Chaos ................................................................................................8 MVL defeated and caught up Nepo before play was suspended Subscription Rates: United Kingdom How Good is Your Chess?..............................................................................21 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 Did you know that Daniel King is a fan of the King’s Gambit? 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 3 year (36 issues) £125 Best of Bunratty ...............................................................................................24 Europe Tim Wall presents more highlights from a weekend in Co. Clare 1 year (12 issues) £60 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 Find the Winning Moves.................................................................................26 3 year (36 issues) £165 Can you do as