Gudgad How the Frogs Came to Be

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Little Flute Music: Mimicry, Memory, and Narrativity

Environmental Humanities, vol. 3, 2013, pp. 43-70 www.environmentalhumanities.org ISSN: 2201-1919 A Little Flute Music: Mimicry, Memory, and Narrativity Vicki Powys, Hollis Taylor and Carol Probets Powys: Independent scholar, Capertee Valley, New South Wales, Australia Taylor: Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia. Probets: Independent scholar, Katoomba, New South Wales, Australia. ABSTRACT A lyrebird chick was raised in captivity in the 1920s in Australia’s New England Tablelands, or so the story goes. The bird mimicked the sounds of the household’s flute player, learning two tunes and an ascending scale. When released back into the wild, his flute-like songs and timbre spread throughout the local lyrebird population. We count ourselves among those who admire the sonic achievements of this bioregion’s “flute lyrebirds.” These Superb Lyrebirds (Menura novaehollandiae) do indeed deliver an unusual and extraordinarily complex, flute-like territorial song, although often with a musical competence exceeding what a human flutist could achieve. In this paper, we engage with both the living and the dead across a wide-ranging cast of characters, linking up in the here and now and grasping a hand across the span of many years. Memory and narrativity are pertinent to the at times conflicting stories and reminiscences from archival and contemporary sources. Ultimately, accounts of “flute lyrebirds” speak to how meaning evolves in the tensions, boundaries, and interplay between knowledge and imagination. We conclude that this story exceeds containment, dispersed as it is across several fields of inquiry and a number of individual memories that go in and out of sync. -

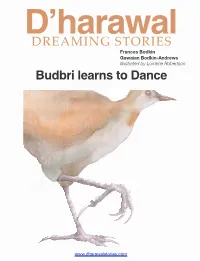

Budbri Learns to Dance DREAMING STORIES

D’harawal DREAMING STORIES Frances Bodkin Gawaian Bodkin-Andrews illustrated by Lorraine Robertson Budbri learns to Dance www.dharawalstories.com Budbri Learns to Dance Frances Bodkin Gawaian Bodkin-Andrews illustrated by Lorraine Robertson www.dharawalstories.com Foreword Throughout the past two hundred years, society has come to regard the Koori Dreaming stories as something akin to the fairy stories they were told as children. However, for thousands upon thousands of years, the stories in this book were used as a teaching tool to impart to the youngest members of the clans the laws which governed the cultural behaviour of clan members. The successive attempts to destroy the Koori culture and assimilate The People into the Euro-centric population were unsuccessful, and the Dreaming Stories were able to continue in their dis- guise as charming legends where animals became the heroes and the heroines. Historians and anthropologists have studied the Koori culture since they first arrived on this continent, and have come to the conclusion that the D’harawal culture is dead. Of, course, this has been done without reference to the descendants of that culture, and without even asking the proper questions. The D’harawal culture is not dead, it is a strong, living, vital culture of the Sydney and South Coast re- gions that just had to go underground for a while to be able to survive. Now that the right questions have been asked, we have the key to unlock a vast wealth of knowledge of this part of the country in which we live. It is difficult to explain to a society based on commerce fuelled by the profit motive, that D’harawal cul- ture is not based on the ownership of tangible things like land and dwellings and possessions, but it does have a very strong sense of ownership of information. -

Download Listening Notes

The Tall Forests of South-East Australia. Morning - Massive eucalypts rise from the forest floor, their crowns spreading high overhead. We begin our forest journey in the coolness of pre-dawn. The air is humid, heavy with Many are of imposing size and great age. The oldest trees may have been mature long the scents of the forest. A small mountain stream flows through the undergrowth, before European people settled this continent. When timber cutters first entered gurgling softly. these forests, they found and felled the tallest trees ever known. The Mountain Ash that remain today are still the tallest hardwood trees, and the tallest flowering plants, Track 1: The Forest Awakens 10.20 in the world. First light dimly filters into the recesses of the forest. Eastern Yellow Robins, usually Below them, forming a luxurious understorey bathed in pools of sunlight, are a tangle the first birds calling, greet the dawn with their loud “Chaf, Chaf” and piping calls of shrubs and ferns. Where conditions are suitable, and fire has not intervened, a true (0:00), and also a soft scolding chatter (especially around 1:44). The cascading trills rainforest has developed; a cool emerald world closing out the sky above. Here tree of a Grey Fantail (0:19, 0:34, 0:52...) and the “chew-ee, chew-ee, chew-ee” of a Satin ferns, some 15 metres high and hundreds of years old, shade an open and moist forest Flycatcher (0:44) join in. floor with fallen logs covered by mosses, liverworts and fungi. A group of Kookaburras, particularly vocal at dawn, make contact and affirm territory We are in an ancient realm. -

Eastern Australia: October-November 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN AUSTRALIA: From Top to Bottom 23rd October – 11th November 2016 The bird of the trip, the very impressive POWERFUL OWL Tour Leader: Laurie Ross All photos in this report were taken by Laurie Ross/Tropical Birding. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 INTRODUCTION The Eastern Australia Set Departure Tour introduces a huge amount of new birds and families to the majority of the group. We started the tour in Cairns in Far North Queensland, where we found ourselves surrounded by multiple habitats from the tidal mudflats of the Cairns Esplanade, the Great Barrier Reef and its sandy cays, lush lowland and highland rainforests of the Atherton Tablelands, and we even made it to the edge of the Outback near Mount Carbine; the next leg of the tour took us south to Southeast Queensland where we spent time in temperate rainforests and wet sclerophyll forests within Lamington National Park. The third, and my favorite leg, of the tour took us down to New South Wales, where we birded a huge variety of new habitats from coastal heathland to rocky shorelines and temperate rainforests in Royal National Park, to the mallee and brigalow of Inland New South Wales. The fourth and final leg of the tour saw us on the beautiful island state of Tasmania, where we found all 13 “Tassie” endemics. We had a huge list of highlights, from finding a roosting Lesser Sooty Owl in Malanda; to finding two roosting Powerful Owls near Brisbane; to having an Albert’s Lyrebird walk out in front of us at O Reilly’s; to seeing the rare and endangered Regent Honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, and finding the endangered Swift Parrot on Bruny Island, in Tasmania. -

Unusual Noisy Miner Display at Blackbutt

Grey Fantail foraging behaviour The Whistler 13 (2019): 81-82 Foraging behaviour by Grey Fantail at the Sugarloaf State Conservation Area, NSW Rob Kyte PO Box 396, Hamilton, NSW 2303, Australia [email protected] Received 12 August 2019; accepted 30 August 2019; published on-line 2 September 2019 Over the past several years I have regularly visited The Grey Fantail was gathering small winged a study site in the Sugarloaf State Conservation insects that had escaped the attention of the Area, near Wakefield, NSW. On three of my visits treecreeper as it foraged. The treecreeper did not I have observed a foraging interaction involving a appear to be bothered in any way. On all three Grey Fantail Rhipidura fuliginosa and a White- occasions when I have observed this behaviour, the throated Treecreeper Cormobates leucophaea. The White-throated Treecreeper seemed completely at behaviour of each bird was quite similar on each ease with the Grey Fantail’s presence. occasion, suggesting that the interaction of the two species was not unusual. There was a clear benefit for the Grey Fantail from this foraging behaviour but there seems no The habitat at the site where the interactions have apparent benefit for the White-throated occurred is dry sclerophyll forest containing Treecreeper. This form of one-way benefit feeding Smooth-barked Apple Angophora costata, Black association is known as commensalism (Campbell She-oak Allocasuarina littoralis, Red Bloodwood & Lack 1985). It may in fact be a characteristic Corymbia gummifera, Ironbark Eucalyptus behaviour by the Grey Fantail. For example, in a sideroxylon and Sydney Peppermint Eucalyptus study in the Maclean River valley in northern piperita, with understorey vegetation that includes NSW, a fantail followed either a treecreeper or a Sandpaper Fig Ficus coronata, Lantana Lantana Brown Gerygone Gerygone mouki on five camara and various grasses. -

By Thomas November 1800 Ery of Superb Lyrebird (Menura Ollandiae)

DISCOVERYDOM OF THE MONTHEDITORIAL 25(86), November 1, 2014 ISSN 2278–5469 EISSN 2278–5450 Discovery Discovery of superb lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) by Thomas Davies on 4 November 1800 Brindha V *Correspondence to: E-mail: [email protected] Publication History Received: 23 September 2014 Accepted: 12 October 2014 Published: 1 November 2014 Citation Brindha V. Discovery of superb lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) by Thomas Davies on 4 November 1800. Discovery, 2014, 25(86), 6 Publication License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. General Note Article is recommended to print as color digital version in recycled paper. The superb lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) is a pheasant-sized Australian song bird. The superb lyrebird is featured on the reverse side of the Australian 10 cent coin. The superb lyrebird can be found in the forests of southeastern Australia, from southern Victoria to southeastern Queensland. Its diet consists mainly of small invertebrates found on the forest floor or in rotting logs. In the 1930s a small number were introduced to Tasmania amongst ill-founded fears it was in danger of becoming extinct. The Tasmanian population is currently thriving. Now widespread and common throughout its large range, the Superb Lyrebird is evaluated as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Superb lyrebirds breed in the depth of winter. Adult males start singing half an hour before sunrise from roosts high above the forest floor. Superb lyrebirds sing less often at other times of year but a stroll through their habitat on a rainy or misty day will sometimes find them active. -

Lyrebird Tales

Lyrebird Tales Volume 26 Number 2 June 2017 Trip to Mud Island by Valerie Fowler thought looked different; perhaps a Cape Gannet? As group 1 was leaving the rocks a boat of divers arrived. A wonderful day was spent out on the bay for the trip to Mud Island. The weather forecast was for a fine but not hot day (23c) with a light breeze increasing as the day warmed up. The group was split into two with the group 1 leaving Blairgowrie jetty at 7am just after the sun rose; they were taken directly to Mud Island. The second group left Blairgowrie at 8.30am stopping alongside Popes Eye Rocks and Chinaman’s Hat before being dropped at Mud Island. The boat then picked up the first group and returned to Blairgowrie via Chinaman’s Hat and Popes Eye Rocks. The boat then returned to Mud Island at 1pm to pick up the second group. Leaving Blairgowrie the water was smooth and we soon saw Silver Gulls, Welcome Swallows, Australasian Gannets, several Terns and Cormorants flying around but they were Australian Gannets photo © V & P Fowler too far away to photograph. Continuing on 3 km to Chinaman’s Hat group 2 saw some Australian Fur Seals leisurely floating in the water with several flippers raised. We approached Chinaman’s Hat which was originally built in 1942 to support defence searchlights but when this structure fell into disrepair Parks Victoria built a new one for the seals which had taken up residence on this floating hotel! The seals preferred the older structure but moved to the new hexagonal structure when the old one was demolished. -

Download the Bird Trail

21/12/10 10:03 AM 10:03 21/12/10 1 ka1479_A3DL_ART2.indd Lithgow Visitor Information Centre Oberon Visitor Information Centre Cnr Ross Street & Edith Road, Oberon Blue Mountains Heritage Centre, Great Western Highway, Glenbrook, Magpies, Honeyeaters, Treecreepers and Fantails. and Treecreepers Honeyeaters, Magpies, Great Western Highway, Lithgow Thornbills, Silvereyes, Scrubwrens, Parrots, Parrots, Scrubwrens, Silvereyes, Thornbills, End of Govetts Leap Raod watering places. These tolerant species include include species tolerant These places. watering visitbluemountains.com.au you are standing quietly near their feeding and and feeding their near quietly standing are you Information Centres: Phone: (02) 4787 8877 Phone: (02) 6329 8210 Echo Point, Katoomba Phone: 1300 760 276 if away, metres few a only from them watch Phone: 1300 653 408 Phone: 1300 653 408 Blue Mountains to you for happy are species bird our of Many National Parks sometimes run ahead of you. of ahead run sometimes along the walking tracks the Bassian Thrush will will Thrush Bassian the tracks walking the along the Eastern Yellow Robin. If you walk slowly slowly walk you If Robin. Yellow Eastern the Shrike-thrush, the Rockwarbler (Origma) and and (Origma) Rockwarbler the Shrike-thrush, few of our most inquisitive species are the Grey Grey the are species inquisitive most our of few O’Connell (from Oberon 238km) (Abercrombie Road Tablelands Wa and Canberra vi To Taralga, Goulburn Bathurs A you. at look and come may birds our of t some view the admiring or rest a picnic, a Call in at any one of our Accredited Visitor Information Centres for advice and assistance from trained local staff. -

International Journal of Comparative Psychology

eScholarship International Journal of Comparative Psychology Title Song Structure and Function of Mimicry in the Australian Magpie (Gymnorhina tibicen): Compared to Lyrebird (Menura ssp.) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/356357r0 Journal International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 12(4) ISSN 0889-3675 Author Kaplan, Gisela Publication Date 1999 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California International Journal of Comparative Psychology, Vol. 12, No. 4, 1999 SONG STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION OF MIMICRY IN THE AUSTRALIAN MAGPIE (Gymnorhina tibicen): COMPARED TO THE LYREBIRD {Menura ssp.) Gisela Kaplan University of New England, AUSTRALIA ABSTRACT: This paper compares two species of songbird with the aim of elucidating the function of song and also of mimicry. It attempts to understand why some birds mimic and takes as examples the lyrebird (Menura sp.) and the Australian magpie {Gymnorhina tibicen). Mimicry by the magpie and its development has been recorded and analysed. The results show that magpies mimic in the wild and they do so mimicking species permanently settled in their own territory. So far 15 types of mimicry have been identified. One handraised Australian magpie even developed the ability to vocalise human language sounds, words and phrases. Results show that mimicry is interspersed into their own song at variable rates, not in fixed sequences as in lyrebirds. In one case it was possible to show an extremely high retention rate of learned material and a high plasticity for learning. Spectrogram comparisons of sequences of mimicry with the calls of the original species, and comparison of magpie mimicry with lyrebird mimicry is made. -

VICTORIA MEGATOUR 2021 19Th-30Th November (12 Days)

SP & AL Starr T/A Firetail Birdwatching Tours. ABN 70397589110. 10 Boardman Close, Box Hill South, Victoria 3128, Australia. Ph: 61438520780 Email: [email protected] Website: www.firetailbirdwatchingtours.com VICTORIA MEGATOUR 2021 19th-30th November (12 days) Features of the Victoria Megatour: Start and finish in Melbourne CBD. Other pick up and drop off locations may be possible. Guided by locals and visiting key birding regions and hotspots targeting rare and iconic birds and animals across all major habitat types. Tour is set up to be medium paced with enough time in the field for good views, photographic opportunities and to connect with rarer and more cryptic birds and animals. A birding tour where photography is welcome but expect that once good views of a bird have been enjoyed we will generally move on.Tour will include some early starts and options for spotlighting activities on some nights to maximise sightings. Opting out of some activities will be possible.With the longer days of early summer a little freetime can be expected on most days . Having fun along the way is non-negotiable ! Your guide enjoys a chat and a laugh especially on the longer drives. This bird watching tour will also include a focus on all aspects of natural history, including time spent observing mammals, reptiles, plants, butterflies and anything else that catches the eye Page 1 Tour Information: Tour length: 12 days Departs: from Melbourne on the morning of Friday 19th November 2021 Concludes: in Melbourne on the evening of Tuesday 30th November 2021 Leader: Simon Starr and local guides as required. -

Foraging Behavioural Ecology of the Superb Lyrebird

FORAGING BEHAVIOURAL ECOLOGY OF THE SUPERB LYREBIRD ALAN LILL Departments of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Psychology, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria 3168 Received 16 November, 1995 Foraging was investigated in a Superb Lyrebird population in southern Victoria. Soil invertebrate food resources were moderately patchily distributed and the fact that foraging effort and success varied greatly spatially suggested that the birds located patches mainly by trial-and-error. The similarity of the nestling's diet, the soil invertebrate fauna and probably the adult's diet, plus the high mean capture rate of 14-18 prey per min foraging, indicated relatively unselective prey consumption by adult lyrebirds. Soil invertebrate abundance exhibited no highly consistent seasonal pattern; however, it showed some tendency to increase in summer and autumn when fledglings were being reared rather than in spring during the period of nestling care. Foraging was probably energetically expensive because >80% of foraging time was spent digging in soil at a mean rate of 78-84 foot movements per min; only 5-8% of foraging time was spent walking or running at a low speed between excavation sites which averaged < 2 m apart. Foraging lyrebirds followed both fairly straight and quite circuitous routes, the latter being more common in the non-breeding season and resulting in intensive exploitation of a localized area. The mean daytime defecation rate (approx. 3 per h) and faecal energy density (8.54-9.28 kJ per g dry mass) indicated that the species probably has a slow gut passage rate, but is highly efficient at assimilating energy from its diet. -

Chapter Four Olivier Messiaen and the Albert's Lyrebird

CHAPTER FOUR OLIVIER MESSIAEN AND THE ALBERT ’S LYREBIRD : F RO M TA M BORINE MOUNTAIN TO ÉCLAIRS SUR L’AU-DELÀ SYDNEY CURTIS AND HOLLIS TAYLOR An Australian ornithologist remembers Olivier Messiaen Olivier Messiaen heard and notated the songs of the two species of lyrebirds, the Albert’s and the Superb, and both appear in his final major work, Illuminations of the Beyond (Éclairs sur l’Au- delà). I will present the background to his hearing an Albert’s Lyrebird and demonstrate something of that species’ musical virtuosity. My colleague, Hollis Taylor, will discuss Messiaen’s transcription and treatment of its song. Messiaen made extensive use of birdsong in his music. I had recorded Superb Lyrebird song where the reverse applied: birds in the wild using human flute music as territorial songs. I thought that would interest Messiaen, so in November 1981 I wrote to him via his publisher, sending him a cassette of lyrebird song, including the “flute” songs, and briefly explaining their history.1 The “flute-mimicking” lyrebirds In the 1920s, a juvenile Superb Lyrebird in captivity, unable to hear adult lyrebirds, modeled his singing on what he could hear: the practice routine of a flute student. He learnt a scale and two simple melodies, “Keel Row” and “The Mosquito Dance.” Lyrebirds are superb mimics, and so in addition to matching the melodies in pitch and tempo, he sang with the tonal quality of a flute. CHAPTER FOUR 53 When released back into the wild, he would have continued his flute songs while also picking up songs and mimicry used by the wild population.