Alec Chisholm and the Extinction of the Paradise Parrot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CITES Hooded Parrot Review

Original language: English AC28 Doc. 20.3.5 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ___________________ Twenty-eighth meeting of the Animals Committee Tel Aviv (Israel), 30 August-3 September 2015 Interpretation and implementation of the Convention Species trade and conservation Periodic review of species included in Appendices I and II [Resolution Conf 14.8 (Rev CoP16)] PERIODIC REVIEW OF PSEPHOTUS DISSIMILIS 1. This document has been submitted by Australia.* 2. After the 25th meeting of the Animals Committee (Geneva, July 2011) and in response to Notification to the Parties No. 2011/038, Australia committed to the evaluation of Psephotus dissimilis as part of the Periodic review of the species included in the CITES Appendices. 3. This taxon is endemic to Australia. 4. Following our review of the status of this species, Australia recommends to maintain Psephotus dissimilis on CITES Appendix I, in accordance with provisions of Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev CoP 16) to allow for further review. * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. AC28 Doc. 20.3.5 – p. 1 AC28 Doc. 20.3.5 Annex CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ DRAFT PROPOSAL TO AMEND THE APPENDICES (in accordance with Annex 4 to Resolution Conf. -

TAG Operational Structure

PARROT TAXON ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Regional Collection Plan 5th Edition 2020-2025 Sustainability of Parrot Populations in AZA Facilities ...................................................................... 1 Mission/Objectives/Strategies......................................................................................................... 2 TAG Operational Structure .............................................................................................................. 3 Steering Committee .................................................................................................................... 3 TAG Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 4 SSP Coordinators ......................................................................................................................... 5 Hot Topics: TAG Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 Parrots as Ambassador Animals .................................................................................................. 9 Interactive Aviaries Housing Psittaciformes .............................................................................. 10 Private Aviculture ...................................................................................................................... 13 Communication ........................................................................................................................ -

A Little Flute Music: Mimicry, Memory, and Narrativity

Environmental Humanities, vol. 3, 2013, pp. 43-70 www.environmentalhumanities.org ISSN: 2201-1919 A Little Flute Music: Mimicry, Memory, and Narrativity Vicki Powys, Hollis Taylor and Carol Probets Powys: Independent scholar, Capertee Valley, New South Wales, Australia Taylor: Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia. Probets: Independent scholar, Katoomba, New South Wales, Australia. ABSTRACT A lyrebird chick was raised in captivity in the 1920s in Australia’s New England Tablelands, or so the story goes. The bird mimicked the sounds of the household’s flute player, learning two tunes and an ascending scale. When released back into the wild, his flute-like songs and timbre spread throughout the local lyrebird population. We count ourselves among those who admire the sonic achievements of this bioregion’s “flute lyrebirds.” These Superb Lyrebirds (Menura novaehollandiae) do indeed deliver an unusual and extraordinarily complex, flute-like territorial song, although often with a musical competence exceeding what a human flutist could achieve. In this paper, we engage with both the living and the dead across a wide-ranging cast of characters, linking up in the here and now and grasping a hand across the span of many years. Memory and narrativity are pertinent to the at times conflicting stories and reminiscences from archival and contemporary sources. Ultimately, accounts of “flute lyrebirds” speak to how meaning evolves in the tensions, boundaries, and interplay between knowledge and imagination. We conclude that this story exceeds containment, dispersed as it is across several fields of inquiry and a number of individual memories that go in and out of sync. -

A8 Targeted Night Parrot Fauna Assessment

10 April 2018 Our Reference: 14279-17-BILR-1Rev0_180410 Fiona Bell Senior Advisor Environmental Approvals Rio Tinto Iron Ore Central Park, 152-158 St Georges Terrace Perth WA 6000 Dear Fiona, Re: Mesa A Hub – Targeted Night Parrot Fauna Assessment, September 2017 1 Introduction Rio Tinto Iron Ore Pty Ltd (Rio Tinto; the Proponent) is evaluating the potential development of a number of iron ore deposits within the Robe Valley, in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. One area under consideration is in the west of the Robe Valley in the vicinity of the mining areas of Mesa A and Warramboo (survey area), located approximately 50 km west of Pannawonica. Key components of the pre-feasibility and feasibility studies being undertaken are environmental surveys which are required to inform the environmental assessment process for the potential development of the survey area. Due to the recent publication of the Interim guideline for preliminary surveys of Night Parrot (Pezoporus occidentalis) (Department of Parks and Wildlife 2017) and to ensure all fauna surveys meet current guidelines, Astron was commissioned to undertake a targeted Night Parrot fauna survey in the survey area (Figure A.1, Attachment A). The possible occurrence of this Matters of National Environmental Significance species within the survey area presents a potential management issue to ground disturbance activities for the development of the Mesa A Hub. In order to improve understanding of the potential for Night Parrot occurrence, habitat utilisation and resident population estimates, a more intensive survey was required within the survey area. 2 Scope of Work The scope of work was to conduct a targeted Night Parrot fauna survey within the survey area in accordance with the scope of works provided by Rio Tinto (dated 17/07/2017), regulatory guidelines (Department of Parks and Wildlife 2017) and industry best practice. -

Night Parrot (Pezoporus Occidentalis) Interim Recovery Plan for Western Australia

Interim Recovery Plan No. 4 INTERIM RECOVERY PLAN NO. 4 NIGHT PARROT (PEZOPORUS OCCIDENTALIS) INTERIM RECOVERY PLAN FOR WESTERN AUSTRALIA 1996 to 1998 by John Blyth March 1996 Department of Conservation and Land Management Western Australian Threatened Species and Communities Unit: WA Wildlife Research Centre, PO Box 51, Wanneroo, WA 6065 Interim Recovery Plan No. 4 FOREWORD Interim Recovery Plans (IRPs) are developed within the framework laid down in Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM) Policy Statements Nos 44 and 50. Where urgency and/or lack of information mean that a full Recovery Plan can not be prepared, IRPs outline the recovery actions required urgently to address those threatening processes most affecting the ongoing survival and begin the recovery process of threatened taxa or ecological communities. CALM is committed to ensuring that Critically Endangered taxa are conserved, through the preparation and implementation of Recovery Plans or Interim Recovery Plans and ensuring that conservation action commences as soon as possible and always within one year of endorsement of that rank by the Minister. This IRP was approved by the Director of Nature Conservation on 21 March, 1996. Approved IRPs are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in status of the taxon or ecological community and the completion of recovery actions. The provision of funds identified in this Interim Recovery Plan is dependent on budgetary and other constraints affecting CALM, as well as the need to address other priorities. Information in this IRP was accurate at 14 March, 1996. ii Interim Recovery Plan No. 4 CONTENTS FOREWORD ........................................................................................................................... iii SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................. -

Special Issue: Genomic Analyses of Avian Evolution

diversity Editorial Special Issue: Genomic Analyses of Avian Evolution Peter Houde Department of Biology, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM 88003, USA; [email protected] Received: 26 September 2019; Accepted: 27 September 2019; Published: 29 September 2019 Abstract: “Genomic Analyses of Avian Evolution” is a “state of the art” showcase of the varied and rapidly evolving fields of inquiry enabled and driven by powerful new methods of genome sequencing and assembly as they are applied to some of the world’s most familiar and charismatic organisms—birds. The contributions to this Special Issue are as eclectic as avian genomics itself, but loosely interrelated by common underpinnings of phylogenetic inference, de novo genome assembly of non-model species, and genome organization and content. Keywords: Aves; phylogenomics; genome assembly; non-model species; genome organization Birds have been the focus of pioneering studies of evolutionary biology for generations, largely because they are abundant, diverse, conspicuous, and charismatic [1]. Ongoing individual and extensively collaborative programs to sequence whole genomes or a variety of pan-genomic markers of all 10,135 described species of living birds further promise to keep birds in the limelight in the near and indefinite future [2,3]. Such comprehensive taxon sampling provides untold opportunities for comparative studies in well documented phenotypic, adaptive, ecological, behavioral, and demographic contexts, while elucidating differing characteristics of evolutionary processes across the genome and among lineages [4,5]. “Genomic Analyses of Avian Evolution” is a timely snapshot of the rapid ontogeny of these diverse endeavors. It features one review and seven original research articles reflecting an eclectic sample of studies loosely interrelated by common themes of phylogenetic inference, de novo genome assembly of non-model species, and genome organization and content. -

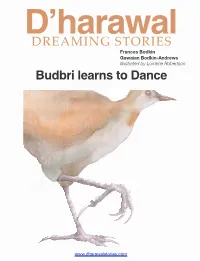

Budbri Learns to Dance DREAMING STORIES

D’harawal DREAMING STORIES Frances Bodkin Gawaian Bodkin-Andrews illustrated by Lorraine Robertson Budbri learns to Dance www.dharawalstories.com Budbri Learns to Dance Frances Bodkin Gawaian Bodkin-Andrews illustrated by Lorraine Robertson www.dharawalstories.com Foreword Throughout the past two hundred years, society has come to regard the Koori Dreaming stories as something akin to the fairy stories they were told as children. However, for thousands upon thousands of years, the stories in this book were used as a teaching tool to impart to the youngest members of the clans the laws which governed the cultural behaviour of clan members. The successive attempts to destroy the Koori culture and assimilate The People into the Euro-centric population were unsuccessful, and the Dreaming Stories were able to continue in their dis- guise as charming legends where animals became the heroes and the heroines. Historians and anthropologists have studied the Koori culture since they first arrived on this continent, and have come to the conclusion that the D’harawal culture is dead. Of, course, this has been done without reference to the descendants of that culture, and without even asking the proper questions. The D’harawal culture is not dead, it is a strong, living, vital culture of the Sydney and South Coast re- gions that just had to go underground for a while to be able to survive. Now that the right questions have been asked, we have the key to unlock a vast wealth of knowledge of this part of the country in which we live. It is difficult to explain to a society based on commerce fuelled by the profit motive, that D’harawal cul- ture is not based on the ownership of tangible things like land and dwellings and possessions, but it does have a very strong sense of ownership of information. -

Australia: from the Wet Tropics to the Outback Custom Tour Trip Report

AUSTRALIA: FROM THE WET TROPICS TO THE OUTBACK CUSTOM TOUR TRIP REPORT 4 – 20 OCTOBER 2018 By Andy Walker We enjoyed excellent views of Little Kingfisher during the tour. www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | TRIP REPORT Australia: From the Wet Tropics to the Outback, October 2018 Overview This 17-day customized Australia group tour commenced in Cairns, Queensland, on the 4th of October 2018 and concluded in Melbourne, Victoria, on the 20th of October 2018. The tour included a circuit around the Atherton Tablelands and surroundings from Cairns, a boat trip along the Daintree River, and a boat trip to the Great Barrier Reef (with snorkeling), a visit to the world- famous O’Reilly’s Rainforest Retreat in southern Queensland after a short flight to Brisbane, and rounded off with a circuit from Melbourne around the southern state of Victoria (and a brief but rewarding venture into southern New South Wales). The tour connected with many exciting birds and yielded a long list of eastern Australian birding specialties. Highlights of our time in Far North Queensland on the Cairns circuit included Southern Cassowary (a close male with chick in perfect light), hundreds of Magpie Geese, Raja Shelduck with young, Green and Cotton Pygmy Geese, Australian Brushturkey, Orange-footed Scrubfowl, Brown Quail, Squatter Pigeon, Wompoo, Superb, and perfect prolonged dawn- light views of stunning Rose-crowned Fruit Doves, displaying Australian Bustard, two nesting Papuan Frogmouths, White-browed Crake, Bush and Beach Stone-curlews (the latter -

According to Dictionary

Extinction: The Parrots We’ve Lost By Desi Milpacher The definition of extinction is “the act or process of becoming extinct; a coming to an end or dying out: the extinction of a species.” Once extinction has been determined, there is usually no chance of a species recurring in a given ecosystem. In mankind’s active history of exploration, exploitation and settlement of new worlds, there has been much loss of natural resources. Parrots have suffered tremendously in this, with over twenty species having been permanently lost. And there are many more that are teetering on the edge, towards the interminable abyss. In this article we find out what happened to these lost treasures, learn which ones are currently being lost, and why this is important to our world. The Old and New Worlds and Their Lost Parrots Little is known of the natural history of most of the world’s extinct parrots, mainly because they disappeared before in-depth studies were conducted on them. It is generally believed, save the Central American macaws which were least known, that most fed on diets similar to today’s parrots (leaves, blossoms, seeds, nuts and fruits), frequented heavy forested areas and nested mainly in tree cavities. A number could not fly well, or were exceptionally tame, leading to their easy capture. Nearly all of these natural treasures vanished between the 18th and early 20th centuries, and the main reason for their loss was overhunting. Some lesser causes included egg collecting (popular with naturalists in the 19th century), diseases (introduced or endemic), drought, natural disasters, predation by introduced species, and habitat alternation. -

Superb Parrot Conservation Research Plan

Superb Parrot Conservation Research Plan Version 2: 29 July 2020 PLAN DATE PREPARED FOR CWP Renewables Pty Ltd Bango Wind Farm Contact 1: Leanne Cross P. (02) 4013 4640 M. 0416 932 549 E. [email protected] Contact 2: Alana Gordijn P. (02) 6100 2122 M. 0414 934 538 E. [email protected] PREPARED BY Dr Laura Rayner P. (02) 6207 7614 M. 0418 414 487 E. [email protected] on behalf of The National Superb Parrot Recovery Team BACKGROUND The Superb Parrot ................................................................................................................................................................2 PURPOSE Commonwealth compliance .......................................................................................................................................................2 PROJECT OVERVIEW Primary aims of proposed research ...................................................................................................................3 SCOPE OF WORK Objectives and approach of proposed research ...................................................................................................3 PROJECT A Understanding local and regional movements of Superb Parrots ....................................................................................................... 3 PROJECT B Understanding the breeding ecology and conservation status of Superb Parrots .......................................................................... 3 SIGNIFICANCE Alignment of project aims with recovery plan objectives -

Download Listening Notes

The Tall Forests of South-East Australia. Morning - Massive eucalypts rise from the forest floor, their crowns spreading high overhead. We begin our forest journey in the coolness of pre-dawn. The air is humid, heavy with Many are of imposing size and great age. The oldest trees may have been mature long the scents of the forest. A small mountain stream flows through the undergrowth, before European people settled this continent. When timber cutters first entered gurgling softly. these forests, they found and felled the tallest trees ever known. The Mountain Ash that remain today are still the tallest hardwood trees, and the tallest flowering plants, Track 1: The Forest Awakens 10.20 in the world. First light dimly filters into the recesses of the forest. Eastern Yellow Robins, usually Below them, forming a luxurious understorey bathed in pools of sunlight, are a tangle the first birds calling, greet the dawn with their loud “Chaf, Chaf” and piping calls of shrubs and ferns. Where conditions are suitable, and fire has not intervened, a true (0:00), and also a soft scolding chatter (especially around 1:44). The cascading trills rainforest has developed; a cool emerald world closing out the sky above. Here tree of a Grey Fantail (0:19, 0:34, 0:52...) and the “chew-ee, chew-ee, chew-ee” of a Satin ferns, some 15 metres high and hundreds of years old, shade an open and moist forest Flycatcher (0:44) join in. floor with fallen logs covered by mosses, liverworts and fungi. A group of Kookaburras, particularly vocal at dawn, make contact and affirm territory We are in an ancient realm. -

Parrot World's Endangered Heavyweight Faces New Threat 13 June 2019

Parrot world's endangered heavyweight faces new threat 13 June 2019 extinct. An intense, decades-long conservation effort has seen kakapo numbers slowly rise from a low of about 50 in 1990, and earlier this year there was hope the species was turning the corner. The breeding programme resulted in 249 eggs laid, fuelling expectations at least 75 chicks would survive the year, more than double the previous record. But Auckland Zoo veterinarian James Chatterton said efforts were now focussed on saving the birds infected by aspergillosis, which before this year was known to have killed just one kakapo. The setback comes just weeks after scientists hailed a bumper breeding season for the flightless, nocturnal bird, which was once thought to be extinct An unprecedented disease outbreak has pushed the critically endangered kakapo, the world's fattest parrot, closer to extinction, New Zealand scientists said Thursday. One of the last kakapo populations on remote Codfish Island has been hit with a fungal respiratory disease called aspergillosis, the Department of Conservation (DOC) said. It said 36 of the parrots were receiving treatment The kakapo - 'night parrot' in Maori - only mates every and seven had died, including two adults—a huge two to four years when New Zealand's native rimu trees are full of fruit loss for a species which has less than 150 fully grown birds left. "Aspergillosis is having a devastating impact on "It's an unprecedented threat and we're working kakapo," the DOC said in a statement Thursday. really hard to understand why it's happened this year," he told TVNZ.