Budbri Learns to Dance DREAMING STORIES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Little Flute Music: Mimicry, Memory, and Narrativity

Environmental Humanities, vol. 3, 2013, pp. 43-70 www.environmentalhumanities.org ISSN: 2201-1919 A Little Flute Music: Mimicry, Memory, and Narrativity Vicki Powys, Hollis Taylor and Carol Probets Powys: Independent scholar, Capertee Valley, New South Wales, Australia Taylor: Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia. Probets: Independent scholar, Katoomba, New South Wales, Australia. ABSTRACT A lyrebird chick was raised in captivity in the 1920s in Australia’s New England Tablelands, or so the story goes. The bird mimicked the sounds of the household’s flute player, learning two tunes and an ascending scale. When released back into the wild, his flute-like songs and timbre spread throughout the local lyrebird population. We count ourselves among those who admire the sonic achievements of this bioregion’s “flute lyrebirds.” These Superb Lyrebirds (Menura novaehollandiae) do indeed deliver an unusual and extraordinarily complex, flute-like territorial song, although often with a musical competence exceeding what a human flutist could achieve. In this paper, we engage with both the living and the dead across a wide-ranging cast of characters, linking up in the here and now and grasping a hand across the span of many years. Memory and narrativity are pertinent to the at times conflicting stories and reminiscences from archival and contemporary sources. Ultimately, accounts of “flute lyrebirds” speak to how meaning evolves in the tensions, boundaries, and interplay between knowledge and imagination. We conclude that this story exceeds containment, dispersed as it is across several fields of inquiry and a number of individual memories that go in and out of sync. -

Recommended Band Size List Page 1

Jun 00 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme - Recommended Band Size List Page 1 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme Recommended Band Size List - Birds of Australia and its Territories Number 24 - May 2000 This list contains all extant bird species which have been recorded for Australia and its Territories, including Antarctica, Norfolk Island, Christmas Island and Cocos and Keeling Islands, with their respective RAOU numbers and band sizes as recommended by the Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme. The list is in two parts: Part 1 is in taxonomic order, based on information in "The Taxonomy and Species of Birds of Australia and its Territories" (1994) by Leslie Christidis and Walter E. Boles, RAOU Monograph 2, RAOU, Melbourne, for non-passerines; and “The Directory of Australian Birds: Passerines” (1999) by R. Schodde and I.J. Mason, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, for passerines. Part 2 is in alphabetic order of common names. The lists include sub-species where these are listed on the Census of Australian Vertebrate Species (CAVS version 8.1, 1994). CHOOSING THE CORRECT BAND Selecting the appropriate band to use combines several factors, including the species to be banded, variability within the species, growth characteristics of the species, and band design. The following list recommends band sizes and metals based on reports from banders, compiled over the life of the ABBBS. For most species, the recommended sizes have been used on substantial numbers of birds. For some species, relatively few individuals have been banded and the size is listed with a question mark. In still other species, too few birds have been banded to justify a size recommendation and none is made. -

Lyrebird Tales

Lyrebird Tales Volume 28 Number 3 September 2019 A TRIP TO THE U.K. 2019 (OR; THOUGHTS TO MULL OVER ) By Doug Pocock Nuthatch photo © Alan Spellman Our bird list started with a Great Heron on the river and then Blue, Long-tailed and Great Tits, Nuthatch, Chaffinch and Rock Wren. We knew we were back in the UK! At the head of the gorge was a small weir and many Sand Martins were feeding on the insects. We were impressed by the local authorities who had installed a large wooden board against a bank of earth and had drilled Martin size holes to enable the birds to breed. Continued on page 2 Contents 1-3. Trip to the UK by Doug Pocock 4. Toora, Gippsland by Warren Cousins 5-6. Challenge for high-rise real estate by Valerie Fowler 6. Interesting sightings. Whose feathers? Committee Looking over Loch na Keal, Mull photo © Alan Spellman 7. Proposed outing to Mud Islands notice. We left home on May 27th and flew one stop to Edinburgh. Lillydale Lake update. Birdlife Yarra Valley camp notice. Here we picked up our hire car and were off. In the past we The one that nearly got away. found it best to pre-book accommodation so we headed for 8-9. Reports of Meetings and Outings New Lanark mill town. This was a fascinating place to stay, built by Richard Owen, an early reformer, as an enlightened 10. Calendar of Events place of employment. For instance he did not employ children under the age of ten instead he provided schooling for them. -

Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Paul Johnsgard Collection Papers in the Biological Sciences 1983 Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants" (1983). Paul Johnsgard Collection. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paul Johnsgard Collection by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. HYBRIDIZATION & ZOOGEOGRAPHIC PATTERNS IN PHEASANTS PAUL A. JOHNSGARD The purpose of this paper is to infonn members of the W.P.A. of an unusual scientific use of the extent and significance of hybridization among pheasants (tribe Phasianini in the proposed classification of Johnsgard~ 1973). This has occasionally occurred naturally, as for example between such locally sympatric species pairs as the kalij (Lophura leucol11elana) and the silver pheasant (L. nycthelnera), but usually occurs "'accidentally" in captive birds, especially in the absence of conspecific mates. Rarely has it been specifically planned for scientific purposes, such as for obtaining genetic, morphological, or biochemical information on hybrid haemoglobins (Brush. 1967), trans ferins (Crozier, 1967), or immunoelectrophoretic comparisons of blood sera (Sato, Ishi and HiraI, 1967). The literature has been summarized by Gray (1958), Delacour (1977), and Rutgers and Norris (1970). Some of these alleged hybrids, especially those not involving other Galliformes, were inadequately doculnented, and in a few cases such as a supposed hybrid between domestic fowl (Gallus gal/us) and the lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) can be discounted. -

Book Reviews Edited by P

Book reviews Edited by P. Dann BANDER'S AID - A GUIDE TO AGEING AND species, plus the three identification keys, mainly of SEXING BUSH BIRDS bush species, although the supplement does contain de- by Ken Rogers, Annie Rogers, Danny Rogers with tails of seven waders. The species descriptions are very assistance from Brett Lane & Bruce Male comprehensive and detailed. They include male and fe- male plumages, as well as immature and juvenile 1986. A. Rogers; St. Andrews, Victoria. Pp. 138, b&w plumages where possible, and details of moult, ageing drawings 12,l map, many tables, 295 x 210 mm. and sexing. This hopefully will act as a spur to many Available from RAOU, $20 (posted). banders and ex-banders to extract information from BANDER'S AID - SUPPLEMENT NUMBER ONE their notebooks and help fill the gaps. by Ken Rogers, Annie Rogers and Danny Rogers The authors have done Australian ornithology a ser- vice by initiating this study. They admit these books are 1990. RAOU; Melbourne. Pp. 76, many tables, 205 x only a starting point and that a lot more data need to be 150 mm. Available from RAOU, $10 (posted). collected. However, if banders can rise to the occasion, These days it is pleasantly surprising to read bird books this approach of cooperative data gathering can lead to that present totally new information about Australian a major advance in our understanding of the regional birds. These two books do just that as the information differences in the morphology of Australian birds. It is they contain is not available from any other source. -

Passerines: Perching Birds

3.9 Orders 9: Passerines – perching birds - Atlas of Birds uncorrected proofs 3.9 Atlas of Birds - Uncorrected proofs Copyrighted Material Passerines: Perching Birds he Passeriformes is by far the largest order of birds, comprising close to 6,000 P Size of order Cardinal virtues Insect-eating voyager Multi-purpose passerine Tspecies. Known loosely as “perching birds”, its members differ from other Number of species in order The Northern or Common Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) The Common Redstart (Phoenicurus phoenicurus) was The Common Magpie (Pica pica) belongs to the crow family orders in various fine anatomical details, and are themselves divided into suborders. Percentage of total bird species belongs to the cardinal family (Cardinalidae) of passerines. once thought to be a member of the thrush family (Corvidae), which includes many of the larger passerines. In simple terms, however, and with a few exceptions, passerines can be described Like the various tanagers, grosbeaks and other members (Turdidae), but is now known to belong to the Old World Like many crows, it is a generalist, with a robust bill adapted of this diverse group, it has a thick, strong bill adapted to flycatchers (Muscicapidae). Its narrow bill is adapted to to feeding on anything from small animals to eggs, carrion, as small birds that sing. feeding on seeds and fruit. Males, from whose vivid red eating insects, and like many insect-eaters that breed in insects, and grain. Crows are among the most intelligent of The word passerine derives from the Latin passer, for sparrow, and indeed a sparrow plumage the family is named, are much more colourful northern Europe and Asia, this species migrates to Sub- birds, and this species is the only non-mammal ever to have is a typical passerine. -

Download Listening Notes

The Tall Forests of South-East Australia. Morning - Massive eucalypts rise from the forest floor, their crowns spreading high overhead. We begin our forest journey in the coolness of pre-dawn. The air is humid, heavy with Many are of imposing size and great age. The oldest trees may have been mature long the scents of the forest. A small mountain stream flows through the undergrowth, before European people settled this continent. When timber cutters first entered gurgling softly. these forests, they found and felled the tallest trees ever known. The Mountain Ash that remain today are still the tallest hardwood trees, and the tallest flowering plants, Track 1: The Forest Awakens 10.20 in the world. First light dimly filters into the recesses of the forest. Eastern Yellow Robins, usually Below them, forming a luxurious understorey bathed in pools of sunlight, are a tangle the first birds calling, greet the dawn with their loud “Chaf, Chaf” and piping calls of shrubs and ferns. Where conditions are suitable, and fire has not intervened, a true (0:00), and also a soft scolding chatter (especially around 1:44). The cascading trills rainforest has developed; a cool emerald world closing out the sky above. Here tree of a Grey Fantail (0:19, 0:34, 0:52...) and the “chew-ee, chew-ee, chew-ee” of a Satin ferns, some 15 metres high and hundreds of years old, shade an open and moist forest Flycatcher (0:44) join in. floor with fallen logs covered by mosses, liverworts and fungi. A group of Kookaburras, particularly vocal at dawn, make contact and affirm territory We are in an ancient realm. -

Eastern Australia: October-November 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN AUSTRALIA: From Top to Bottom 23rd October – 11th November 2016 The bird of the trip, the very impressive POWERFUL OWL Tour Leader: Laurie Ross All photos in this report were taken by Laurie Ross/Tropical Birding. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 INTRODUCTION The Eastern Australia Set Departure Tour introduces a huge amount of new birds and families to the majority of the group. We started the tour in Cairns in Far North Queensland, where we found ourselves surrounded by multiple habitats from the tidal mudflats of the Cairns Esplanade, the Great Barrier Reef and its sandy cays, lush lowland and highland rainforests of the Atherton Tablelands, and we even made it to the edge of the Outback near Mount Carbine; the next leg of the tour took us south to Southeast Queensland where we spent time in temperate rainforests and wet sclerophyll forests within Lamington National Park. The third, and my favorite leg, of the tour took us down to New South Wales, where we birded a huge variety of new habitats from coastal heathland to rocky shorelines and temperate rainforests in Royal National Park, to the mallee and brigalow of Inland New South Wales. The fourth and final leg of the tour saw us on the beautiful island state of Tasmania, where we found all 13 “Tassie” endemics. We had a huge list of highlights, from finding a roosting Lesser Sooty Owl in Malanda; to finding two roosting Powerful Owls near Brisbane; to having an Albert’s Lyrebird walk out in front of us at O Reilly’s; to seeing the rare and endangered Regent Honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, and finding the endangered Swift Parrot on Bruny Island, in Tasmania. -

Unusual Noisy Miner Display at Blackbutt

Grey Fantail foraging behaviour The Whistler 13 (2019): 81-82 Foraging behaviour by Grey Fantail at the Sugarloaf State Conservation Area, NSW Rob Kyte PO Box 396, Hamilton, NSW 2303, Australia [email protected] Received 12 August 2019; accepted 30 August 2019; published on-line 2 September 2019 Over the past several years I have regularly visited The Grey Fantail was gathering small winged a study site in the Sugarloaf State Conservation insects that had escaped the attention of the Area, near Wakefield, NSW. On three of my visits treecreeper as it foraged. The treecreeper did not I have observed a foraging interaction involving a appear to be bothered in any way. On all three Grey Fantail Rhipidura fuliginosa and a White- occasions when I have observed this behaviour, the throated Treecreeper Cormobates leucophaea. The White-throated Treecreeper seemed completely at behaviour of each bird was quite similar on each ease with the Grey Fantail’s presence. occasion, suggesting that the interaction of the two species was not unusual. There was a clear benefit for the Grey Fantail from this foraging behaviour but there seems no The habitat at the site where the interactions have apparent benefit for the White-throated occurred is dry sclerophyll forest containing Treecreeper. This form of one-way benefit feeding Smooth-barked Apple Angophora costata, Black association is known as commensalism (Campbell She-oak Allocasuarina littoralis, Red Bloodwood & Lack 1985). It may in fact be a characteristic Corymbia gummifera, Ironbark Eucalyptus behaviour by the Grey Fantail. For example, in a sideroxylon and Sydney Peppermint Eucalyptus study in the Maclean River valley in northern piperita, with understorey vegetation that includes NSW, a fantail followed either a treecreeper or a Sandpaper Fig Ficus coronata, Lantana Lantana Brown Gerygone Gerygone mouki on five camara and various grasses. -

Supplementary Information For

Supplementary Information for Earth history and the passerine superradiation Oliveros, Carl H., Daniel J. Field, Daniel T. Ksepka, F. Keith Barker, Alexandre Aleixo, Michael J. Andersen, Per Alström, Brett W. Benz, Edward L. Braun, Michael J. Braun, Gustavo A. Bravo, Robb T. Brumfield, R. Terry Chesser, Santiago Claramunt, Joel Cracraft, Andrés M. Cuervo, Elizabeth P. Derryberry, Travis C. Glenn, Michael G. Harvey, Peter A. Hosner, Leo Joseph, Rebecca Kimball, Andrew L. Mack, Colin M. Miskelly, A. Townsend Peterson, Mark B. Robbins, Frederick H. Sheldon, Luís Fábio Silveira, Brian T. Smith, Noor D. White, Robert G. Moyle, Brant C. Faircloth Corresponding authors: Carl H. Oliveros, Email: [email protected] Brant C. Faircloth, Email: [email protected] This PDF file includes: Supplementary text Figs. S1 to S10 Table S1 to S3 References for SI reference citations Other supplementary materials for this manuscript include the following: Supplementary Files S1 to S3 1 www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1813206116 Supplementary Information Text Extended Materials and Methods Library preparation and sequencing. We extracted and purified DNA from fresh muscle tissue, liver tissue, or toepad clips from 113 vouchered museum specimens (Supplementary File S1) using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit following the manufacturer’s protocol. We quantified DNA extracts using a Qubit fluorometer, and we prepared aliquots of DNA extracted from muscle and liver at 10 ng/µL in 60 µL volume for shearing. We sheared each DNA sample to 400–600 bp using a Qsonica Q800R sonicator for 15–45 cycles, with each cycle running for 20 seconds on and 20 seconds off at 25% amplitude. -

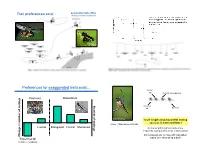

Preferences for Exaggerated Traits Exist… Control I ! Control II (Unmanipulated)

Long-tailed dance flies Long-tailed dance fly – Rhamphomyia longicauda Trait preferences exist… Rhamphomyia longicauda Preferences for exaggerated traits exist… Control I ! Control II (unmanipulated) Peacocks Widowbirds Number of matings Shortened ! Elongated barn swallow Is tail length associated with mating success in barn swallows? Moller (1988) Nature 332:640 Control Elongated Control Shortened Do males with long tails mate more frequently (compared to short-tailed males)? Do females prefer to mate with long tailed Change in number of matings Experimental males over short-tailed males? (remove eyesptos) ! ! ! ! barn swallow barn swallow Moller (1988) Nature 332:640 Moller (1988) Nature 332:640 Males with elongated tails found Males with elongated tails mates more quickly re-mated more frequently …but what is it that males (or females) choosing? Hypotheses for how mate choice evolves... ! ! • Honest advertisement • Individuals increase their fitness by selecting mates whose characteristics indicate that they are of high quality. • Direct benefits to individuals of the choosy sex • Indirect benefits (e.g., good genes for offspring of choosy sex) barn swallow Females paired with short-tailed males more likely to accept extra matings Males with elongated tails had more offspring long-tailed males were Extra pair copulations more successful at By males gaining extra matings By their female pair- mates Indirect benefits: Good genes hypothesis Direct benefits: food In nature… Bittacus apicalis Exaggerated traits indicate the genetic quality -

Wiritjiribin-9-9Kb.Pdf

D’harawal DREAMING STORIES Frances Bodkin Gawaian Bodkin-Andrews illustrated by Lorraine Robertson Wiritjiribin The First Lyrebird www.dharawalstories.com Wiritjiribin The First Lyrebird Frances Bodkin Gawaian Bodkin-Andrews illustrated by Lorraine Robertson www.dharawalstories.com i Foreword Throughout the past two hundred years, society has come to regard the Koori Dreaming stories as something akin to the fairy stories they were told as children. However, for thousands upon thousands of years, the stories in this book were used as a teaching tool to impart to the youngest members of the clans the laws which governed the cultural behaviour of clan members. The successive attempts to destroy the Koori culture and assimilate The People into the Euro-centric population were unsuccessful, and the Dreaming Stories were able to continue in their dis- guise as charming legends where animals became the heroes and the heroines. Historians and anthropologists have studied the Koori culture since they first arrived on this continent, and have come to the conclusion that the D’harawal culture is dead. Of, course, this has been done without reference to the descendants of that culture, and without even asking the proper questions. The D’harawal culture is not dead, it is a strong, living, vital culture of the Sydney and South Coast re- gions that just had to go underground for a while to be able to survive. Now that the right questions have been asked, we have the key to unlock a vast wealth of knowledge of this part of the country in which we live. It is difficult to explain to a society based on commerce fuelled by the profit motive, that D’harawal cul- ture is not based on the ownership of tangible things like land and dwellings and possessions, but it does have a very strong sense of ownership of information.