Wiritjiribin-9-9Kb.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Little Flute Music: Mimicry, Memory, and Narrativity

Environmental Humanities, vol. 3, 2013, pp. 43-70 www.environmentalhumanities.org ISSN: 2201-1919 A Little Flute Music: Mimicry, Memory, and Narrativity Vicki Powys, Hollis Taylor and Carol Probets Powys: Independent scholar, Capertee Valley, New South Wales, Australia Taylor: Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia. Probets: Independent scholar, Katoomba, New South Wales, Australia. ABSTRACT A lyrebird chick was raised in captivity in the 1920s in Australia’s New England Tablelands, or so the story goes. The bird mimicked the sounds of the household’s flute player, learning two tunes and an ascending scale. When released back into the wild, his flute-like songs and timbre spread throughout the local lyrebird population. We count ourselves among those who admire the sonic achievements of this bioregion’s “flute lyrebirds.” These Superb Lyrebirds (Menura novaehollandiae) do indeed deliver an unusual and extraordinarily complex, flute-like territorial song, although often with a musical competence exceeding what a human flutist could achieve. In this paper, we engage with both the living and the dead across a wide-ranging cast of characters, linking up in the here and now and grasping a hand across the span of many years. Memory and narrativity are pertinent to the at times conflicting stories and reminiscences from archival and contemporary sources. Ultimately, accounts of “flute lyrebirds” speak to how meaning evolves in the tensions, boundaries, and interplay between knowledge and imagination. We conclude that this story exceeds containment, dispersed as it is across several fields of inquiry and a number of individual memories that go in and out of sync. -

Recommended Band Size List Page 1

Jun 00 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme - Recommended Band Size List Page 1 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme Recommended Band Size List - Birds of Australia and its Territories Number 24 - May 2000 This list contains all extant bird species which have been recorded for Australia and its Territories, including Antarctica, Norfolk Island, Christmas Island and Cocos and Keeling Islands, with their respective RAOU numbers and band sizes as recommended by the Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme. The list is in two parts: Part 1 is in taxonomic order, based on information in "The Taxonomy and Species of Birds of Australia and its Territories" (1994) by Leslie Christidis and Walter E. Boles, RAOU Monograph 2, RAOU, Melbourne, for non-passerines; and “The Directory of Australian Birds: Passerines” (1999) by R. Schodde and I.J. Mason, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, for passerines. Part 2 is in alphabetic order of common names. The lists include sub-species where these are listed on the Census of Australian Vertebrate Species (CAVS version 8.1, 1994). CHOOSING THE CORRECT BAND Selecting the appropriate band to use combines several factors, including the species to be banded, variability within the species, growth characteristics of the species, and band design. The following list recommends band sizes and metals based on reports from banders, compiled over the life of the ABBBS. For most species, the recommended sizes have been used on substantial numbers of birds. For some species, relatively few individuals have been banded and the size is listed with a question mark. In still other species, too few birds have been banded to justify a size recommendation and none is made. -

Budbri Learns to Dance DREAMING STORIES

D’harawal DREAMING STORIES Frances Bodkin Gawaian Bodkin-Andrews illustrated by Lorraine Robertson Budbri learns to Dance www.dharawalstories.com Budbri Learns to Dance Frances Bodkin Gawaian Bodkin-Andrews illustrated by Lorraine Robertson www.dharawalstories.com Foreword Throughout the past two hundred years, society has come to regard the Koori Dreaming stories as something akin to the fairy stories they were told as children. However, for thousands upon thousands of years, the stories in this book were used as a teaching tool to impart to the youngest members of the clans the laws which governed the cultural behaviour of clan members. The successive attempts to destroy the Koori culture and assimilate The People into the Euro-centric population were unsuccessful, and the Dreaming Stories were able to continue in their dis- guise as charming legends where animals became the heroes and the heroines. Historians and anthropologists have studied the Koori culture since they first arrived on this continent, and have come to the conclusion that the D’harawal culture is dead. Of, course, this has been done without reference to the descendants of that culture, and without even asking the proper questions. The D’harawal culture is not dead, it is a strong, living, vital culture of the Sydney and South Coast re- gions that just had to go underground for a while to be able to survive. Now that the right questions have been asked, we have the key to unlock a vast wealth of knowledge of this part of the country in which we live. It is difficult to explain to a society based on commerce fuelled by the profit motive, that D’harawal cul- ture is not based on the ownership of tangible things like land and dwellings and possessions, but it does have a very strong sense of ownership of information. -

Lyrebird Tales

Lyrebird Tales Volume 28 Number 3 September 2019 A TRIP TO THE U.K. 2019 (OR; THOUGHTS TO MULL OVER ) By Doug Pocock Nuthatch photo © Alan Spellman Our bird list started with a Great Heron on the river and then Blue, Long-tailed and Great Tits, Nuthatch, Chaffinch and Rock Wren. We knew we were back in the UK! At the head of the gorge was a small weir and many Sand Martins were feeding on the insects. We were impressed by the local authorities who had installed a large wooden board against a bank of earth and had drilled Martin size holes to enable the birds to breed. Continued on page 2 Contents 1-3. Trip to the UK by Doug Pocock 4. Toora, Gippsland by Warren Cousins 5-6. Challenge for high-rise real estate by Valerie Fowler 6. Interesting sightings. Whose feathers? Committee Looking over Loch na Keal, Mull photo © Alan Spellman 7. Proposed outing to Mud Islands notice. We left home on May 27th and flew one stop to Edinburgh. Lillydale Lake update. Birdlife Yarra Valley camp notice. Here we picked up our hire car and were off. In the past we The one that nearly got away. found it best to pre-book accommodation so we headed for 8-9. Reports of Meetings and Outings New Lanark mill town. This was a fascinating place to stay, built by Richard Owen, an early reformer, as an enlightened 10. Calendar of Events place of employment. For instance he did not employ children under the age of ten instead he provided schooling for them. -

Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Paul Johnsgard Collection Papers in the Biological Sciences 1983 Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants" (1983). Paul Johnsgard Collection. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paul Johnsgard Collection by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. HYBRIDIZATION & ZOOGEOGRAPHIC PATTERNS IN PHEASANTS PAUL A. JOHNSGARD The purpose of this paper is to infonn members of the W.P.A. of an unusual scientific use of the extent and significance of hybridization among pheasants (tribe Phasianini in the proposed classification of Johnsgard~ 1973). This has occasionally occurred naturally, as for example between such locally sympatric species pairs as the kalij (Lophura leucol11elana) and the silver pheasant (L. nycthelnera), but usually occurs "'accidentally" in captive birds, especially in the absence of conspecific mates. Rarely has it been specifically planned for scientific purposes, such as for obtaining genetic, morphological, or biochemical information on hybrid haemoglobins (Brush. 1967), trans ferins (Crozier, 1967), or immunoelectrophoretic comparisons of blood sera (Sato, Ishi and HiraI, 1967). The literature has been summarized by Gray (1958), Delacour (1977), and Rutgers and Norris (1970). Some of these alleged hybrids, especially those not involving other Galliformes, were inadequately doculnented, and in a few cases such as a supposed hybrid between domestic fowl (Gallus gal/us) and the lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) can be discounted. -

Book Reviews Edited by P

Book reviews Edited by P. Dann BANDER'S AID - A GUIDE TO AGEING AND species, plus the three identification keys, mainly of SEXING BUSH BIRDS bush species, although the supplement does contain de- by Ken Rogers, Annie Rogers, Danny Rogers with tails of seven waders. The species descriptions are very assistance from Brett Lane & Bruce Male comprehensive and detailed. They include male and fe- male plumages, as well as immature and juvenile 1986. A. Rogers; St. Andrews, Victoria. Pp. 138, b&w plumages where possible, and details of moult, ageing drawings 12,l map, many tables, 295 x 210 mm. and sexing. This hopefully will act as a spur to many Available from RAOU, $20 (posted). banders and ex-banders to extract information from BANDER'S AID - SUPPLEMENT NUMBER ONE their notebooks and help fill the gaps. by Ken Rogers, Annie Rogers and Danny Rogers The authors have done Australian ornithology a ser- vice by initiating this study. They admit these books are 1990. RAOU; Melbourne. Pp. 76, many tables, 205 x only a starting point and that a lot more data need to be 150 mm. Available from RAOU, $10 (posted). collected. However, if banders can rise to the occasion, These days it is pleasantly surprising to read bird books this approach of cooperative data gathering can lead to that present totally new information about Australian a major advance in our understanding of the regional birds. These two books do just that as the information differences in the morphology of Australian birds. It is they contain is not available from any other source. -

Passerines: Perching Birds

3.9 Orders 9: Passerines – perching birds - Atlas of Birds uncorrected proofs 3.9 Atlas of Birds - Uncorrected proofs Copyrighted Material Passerines: Perching Birds he Passeriformes is by far the largest order of birds, comprising close to 6,000 P Size of order Cardinal virtues Insect-eating voyager Multi-purpose passerine Tspecies. Known loosely as “perching birds”, its members differ from other Number of species in order The Northern or Common Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) The Common Redstart (Phoenicurus phoenicurus) was The Common Magpie (Pica pica) belongs to the crow family orders in various fine anatomical details, and are themselves divided into suborders. Percentage of total bird species belongs to the cardinal family (Cardinalidae) of passerines. once thought to be a member of the thrush family (Corvidae), which includes many of the larger passerines. In simple terms, however, and with a few exceptions, passerines can be described Like the various tanagers, grosbeaks and other members (Turdidae), but is now known to belong to the Old World Like many crows, it is a generalist, with a robust bill adapted of this diverse group, it has a thick, strong bill adapted to flycatchers (Muscicapidae). Its narrow bill is adapted to to feeding on anything from small animals to eggs, carrion, as small birds that sing. feeding on seeds and fruit. Males, from whose vivid red eating insects, and like many insect-eaters that breed in insects, and grain. Crows are among the most intelligent of The word passerine derives from the Latin passer, for sparrow, and indeed a sparrow plumage the family is named, are much more colourful northern Europe and Asia, this species migrates to Sub- birds, and this species is the only non-mammal ever to have is a typical passerine. -

Supplementary Information For

Supplementary Information for Earth history and the passerine superradiation Oliveros, Carl H., Daniel J. Field, Daniel T. Ksepka, F. Keith Barker, Alexandre Aleixo, Michael J. Andersen, Per Alström, Brett W. Benz, Edward L. Braun, Michael J. Braun, Gustavo A. Bravo, Robb T. Brumfield, R. Terry Chesser, Santiago Claramunt, Joel Cracraft, Andrés M. Cuervo, Elizabeth P. Derryberry, Travis C. Glenn, Michael G. Harvey, Peter A. Hosner, Leo Joseph, Rebecca Kimball, Andrew L. Mack, Colin M. Miskelly, A. Townsend Peterson, Mark B. Robbins, Frederick H. Sheldon, Luís Fábio Silveira, Brian T. Smith, Noor D. White, Robert G. Moyle, Brant C. Faircloth Corresponding authors: Carl H. Oliveros, Email: [email protected] Brant C. Faircloth, Email: [email protected] This PDF file includes: Supplementary text Figs. S1 to S10 Table S1 to S3 References for SI reference citations Other supplementary materials for this manuscript include the following: Supplementary Files S1 to S3 1 www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1813206116 Supplementary Information Text Extended Materials and Methods Library preparation and sequencing. We extracted and purified DNA from fresh muscle tissue, liver tissue, or toepad clips from 113 vouchered museum specimens (Supplementary File S1) using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit following the manufacturer’s protocol. We quantified DNA extracts using a Qubit fluorometer, and we prepared aliquots of DNA extracted from muscle and liver at 10 ng/µL in 60 µL volume for shearing. We sheared each DNA sample to 400–600 bp using a Qsonica Q800R sonicator for 15–45 cycles, with each cycle running for 20 seconds on and 20 seconds off at 25% amplitude. -

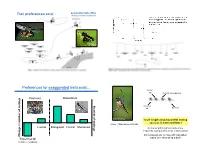

Preferences for Exaggerated Traits Exist… Control I ! Control II (Unmanipulated)

Long-tailed dance flies Long-tailed dance fly – Rhamphomyia longicauda Trait preferences exist… Rhamphomyia longicauda Preferences for exaggerated traits exist… Control I ! Control II (unmanipulated) Peacocks Widowbirds Number of matings Shortened ! Elongated barn swallow Is tail length associated with mating success in barn swallows? Moller (1988) Nature 332:640 Control Elongated Control Shortened Do males with long tails mate more frequently (compared to short-tailed males)? Do females prefer to mate with long tailed Change in number of matings Experimental males over short-tailed males? (remove eyesptos) ! ! ! ! barn swallow barn swallow Moller (1988) Nature 332:640 Moller (1988) Nature 332:640 Males with elongated tails found Males with elongated tails mates more quickly re-mated more frequently …but what is it that males (or females) choosing? Hypotheses for how mate choice evolves... ! ! • Honest advertisement • Individuals increase their fitness by selecting mates whose characteristics indicate that they are of high quality. • Direct benefits to individuals of the choosy sex • Indirect benefits (e.g., good genes for offspring of choosy sex) barn swallow Females paired with short-tailed males more likely to accept extra matings Males with elongated tails had more offspring long-tailed males were Extra pair copulations more successful at By males gaining extra matings By their female pair- mates Indirect benefits: Good genes hypothesis Direct benefits: food In nature… Bittacus apicalis Exaggerated traits indicate the genetic quality -

International Journal of Comparative Psychology

eScholarship International Journal of Comparative Psychology Title Song Structure and Function of Mimicry in the Australian Magpie (Gymnorhina tibicen): Compared to Lyrebird (Menura ssp.) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/356357r0 Journal International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 12(4) ISSN 0889-3675 Author Kaplan, Gisela Publication Date 1999 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California International Journal of Comparative Psychology, Vol. 12, No. 4, 1999 SONG STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION OF MIMICRY IN THE AUSTRALIAN MAGPIE (Gymnorhina tibicen): COMPARED TO THE LYREBIRD {Menura ssp.) Gisela Kaplan University of New England, AUSTRALIA ABSTRACT: This paper compares two species of songbird with the aim of elucidating the function of song and also of mimicry. It attempts to understand why some birds mimic and takes as examples the lyrebird (Menura sp.) and the Australian magpie {Gymnorhina tibicen). Mimicry by the magpie and its development has been recorded and analysed. The results show that magpies mimic in the wild and they do so mimicking species permanently settled in their own territory. So far 15 types of mimicry have been identified. One handraised Australian magpie even developed the ability to vocalise human language sounds, words and phrases. Results show that mimicry is interspersed into their own song at variable rates, not in fixed sequences as in lyrebirds. In one case it was possible to show an extremely high retention rate of learned material and a high plasticity for learning. Spectrogram comparisons of sequences of mimicry with the calls of the original species, and comparison of magpie mimicry with lyrebird mimicry is made. -

Foraging Behavioural Ecology of the Superb Lyrebird

FORAGING BEHAVIOURAL ECOLOGY OF THE SUPERB LYREBIRD ALAN LILL Departments of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Psychology, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria 3168 Received 16 November, 1995 Foraging was investigated in a Superb Lyrebird population in southern Victoria. Soil invertebrate food resources were moderately patchily distributed and the fact that foraging effort and success varied greatly spatially suggested that the birds located patches mainly by trial-and-error. The similarity of the nestling's diet, the soil invertebrate fauna and probably the adult's diet, plus the high mean capture rate of 14-18 prey per min foraging, indicated relatively unselective prey consumption by adult lyrebirds. Soil invertebrate abundance exhibited no highly consistent seasonal pattern; however, it showed some tendency to increase in summer and autumn when fledglings were being reared rather than in spring during the period of nestling care. Foraging was probably energetically expensive because >80% of foraging time was spent digging in soil at a mean rate of 78-84 foot movements per min; only 5-8% of foraging time was spent walking or running at a low speed between excavation sites which averaged < 2 m apart. Foraging lyrebirds followed both fairly straight and quite circuitous routes, the latter being more common in the non-breeding season and resulting in intensive exploitation of a localized area. The mean daytime defecation rate (approx. 3 per h) and faecal energy density (8.54-9.28 kJ per g dry mass) indicated that the species probably has a slow gut passage rate, but is highly efficient at assimilating energy from its diet. -

The Avian Cecum: a Review

Wilson Bull., 107(l), 1995, pp. 93-121 THE AVIAN CECUM: A REVIEW MARY H. CLENCH AND JOHN R. MATHIAS ’ ABSTRACT.-The ceca, intestinal outpocketings of the gut, are described, classified by types, and their occurrence surveyed across the Order Aves. Correlation between cecal size and systematic position is weak except among closely related species. With many exceptions, herbivores and omnivores tend to have large ceca, insectivores and carnivores are variable, and piscivores and graminivores have small ceca. Although important progress has been made in recent years, especially through the use of wild birds under natural (or quasi-natural) conditions rather than studying domestic species in captivity, much remains to be learned about cecal functioning. Research on periodic changes in galliform and anseriform cecal size in response to dietary alterations is discussed. Studies demonstrating cellulose digestion and fermentation in ceca, and their utilization and absorption of water, nitrogenous com- pounds, and other nutrients are reviewed. We also note disease-causing organisms that may be found in ceca. The avian cecum is a multi-purpose organ, with the potential to act in many different ways-and depending on the species involved, its cecal morphology, and ecological conditions, cecal functioning can be efficient and vitally important to a birds’ physiology, especially during periods of stress. Received 14 Feb. 1994, accepted 2 June 1994. The digestive tract of most birds contains a pair of outpocketings that project from the proximal colon at its junction with the small intestine (Fig. 1). These ceca are usually fingerlike in shape, looking much like simple lateral extensions of the intestine, but some are complex in struc- ture.