A Little Flute Music: Mimicry, Memory, and Narrativity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Little Flute Music: Mimicry, Memory, and Narrativity

Environmental Humanities, vol. 3, 2013, pp. 43-70 www.environmentalhumanities.org ISSN: 2201-1919 A Little Flute Music: Mimicry, Memory, and Narrativity Vicki Powys, Hollis Taylor and Carol Probets Powys: Independent scholar, Capertee Valley, New South Wales, Australia Taylor: Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia. Probets: Independent scholar, Katoomba, New South Wales, Australia. ABSTRACT A lyrebird chick was raised in captivity in the 1920s in Australia’s New England Tablelands, or so the story goes. The bird mimicked the sounds of the household’s flute player, learning two tunes and an ascending scale. When released back into the wild, his flute-like songs and timbre spread throughout the local lyrebird population. We count ourselves among those who admire the sonic achievements of this bioregion’s “flute lyrebirds.” These Superb Lyrebirds (Menura novaehollandiae) do indeed deliver an unusual and extraordinarily complex, flute-like territorial song, although often with a musical competence exceeding what a human flutist could achieve. In this paper, we engage with both the living and the dead across a wide-ranging cast of characters, linking up in the here and now and grasping a hand across the span of many years. Memory and narrativity are pertinent to the at times conflicting stories and reminiscences from archival and contemporary sources. Ultimately, accounts of “flute lyrebirds” speak to how meaning evolves in the tensions, boundaries, and interplay between knowledge and imagination. We conclude that this story exceeds containment, dispersed as it is across several fields of inquiry and a number of individual memories that go in and out of sync. -

Recommended Band Size List Page 1

Jun 00 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme - Recommended Band Size List Page 1 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme Recommended Band Size List - Birds of Australia and its Territories Number 24 - May 2000 This list contains all extant bird species which have been recorded for Australia and its Territories, including Antarctica, Norfolk Island, Christmas Island and Cocos and Keeling Islands, with their respective RAOU numbers and band sizes as recommended by the Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme. The list is in two parts: Part 1 is in taxonomic order, based on information in "The Taxonomy and Species of Birds of Australia and its Territories" (1994) by Leslie Christidis and Walter E. Boles, RAOU Monograph 2, RAOU, Melbourne, for non-passerines; and “The Directory of Australian Birds: Passerines” (1999) by R. Schodde and I.J. Mason, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, for passerines. Part 2 is in alphabetic order of common names. The lists include sub-species where these are listed on the Census of Australian Vertebrate Species (CAVS version 8.1, 1994). CHOOSING THE CORRECT BAND Selecting the appropriate band to use combines several factors, including the species to be banded, variability within the species, growth characteristics of the species, and band design. The following list recommends band sizes and metals based on reports from banders, compiled over the life of the ABBBS. For most species, the recommended sizes have been used on substantial numbers of birds. For some species, relatively few individuals have been banded and the size is listed with a question mark. In still other species, too few birds have been banded to justify a size recommendation and none is made. -

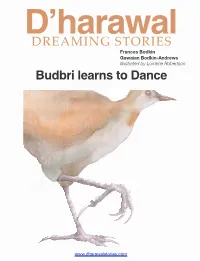

Budbri Learns to Dance DREAMING STORIES

D’harawal DREAMING STORIES Frances Bodkin Gawaian Bodkin-Andrews illustrated by Lorraine Robertson Budbri learns to Dance www.dharawalstories.com Budbri Learns to Dance Frances Bodkin Gawaian Bodkin-Andrews illustrated by Lorraine Robertson www.dharawalstories.com Foreword Throughout the past two hundred years, society has come to regard the Koori Dreaming stories as something akin to the fairy stories they were told as children. However, for thousands upon thousands of years, the stories in this book were used as a teaching tool to impart to the youngest members of the clans the laws which governed the cultural behaviour of clan members. The successive attempts to destroy the Koori culture and assimilate The People into the Euro-centric population were unsuccessful, and the Dreaming Stories were able to continue in their dis- guise as charming legends where animals became the heroes and the heroines. Historians and anthropologists have studied the Koori culture since they first arrived on this continent, and have come to the conclusion that the D’harawal culture is dead. Of, course, this has been done without reference to the descendants of that culture, and without even asking the proper questions. The D’harawal culture is not dead, it is a strong, living, vital culture of the Sydney and South Coast re- gions that just had to go underground for a while to be able to survive. Now that the right questions have been asked, we have the key to unlock a vast wealth of knowledge of this part of the country in which we live. It is difficult to explain to a society based on commerce fuelled by the profit motive, that D’harawal cul- ture is not based on the ownership of tangible things like land and dwellings and possessions, but it does have a very strong sense of ownership of information. -

Lyrebird Tales

Lyrebird Tales Volume 28 Number 3 September 2019 A TRIP TO THE U.K. 2019 (OR; THOUGHTS TO MULL OVER ) By Doug Pocock Nuthatch photo © Alan Spellman Our bird list started with a Great Heron on the river and then Blue, Long-tailed and Great Tits, Nuthatch, Chaffinch and Rock Wren. We knew we were back in the UK! At the head of the gorge was a small weir and many Sand Martins were feeding on the insects. We were impressed by the local authorities who had installed a large wooden board against a bank of earth and had drilled Martin size holes to enable the birds to breed. Continued on page 2 Contents 1-3. Trip to the UK by Doug Pocock 4. Toora, Gippsland by Warren Cousins 5-6. Challenge for high-rise real estate by Valerie Fowler 6. Interesting sightings. Whose feathers? Committee Looking over Loch na Keal, Mull photo © Alan Spellman 7. Proposed outing to Mud Islands notice. We left home on May 27th and flew one stop to Edinburgh. Lillydale Lake update. Birdlife Yarra Valley camp notice. Here we picked up our hire car and were off. In the past we The one that nearly got away. found it best to pre-book accommodation so we headed for 8-9. Reports of Meetings and Outings New Lanark mill town. This was a fascinating place to stay, built by Richard Owen, an early reformer, as an enlightened 10. Calendar of Events place of employment. For instance he did not employ children under the age of ten instead he provided schooling for them. -

The Evolution of Human Vocal Emotion

EMR0010.1177/1754073920930791Emotion ReviewBryant 930791research-article2020 SPECIAL SECTION: EMOTION IN THE VOICE Emotion Review Vol. 13, No. 1 (January 2021) 25 –33 © The Author(s) 2020 ISSN 1754-0739 DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073920930791 10.1177/1754073920930791 The Evolution of Human Vocal Emotion https://journals.sagepub.com/home/emr Gregory A. Bryant Department of Communication, Center for Behavior, Evolution, and Culture, University of California, Los Angeles, USA Abstract Vocal affect is a subcomponent of emotion programs that coordinate a variety of physiological and psychological systems. Emotional vocalizations comprise a suite of vocal behaviors shaped by evolution to solve adaptive social communication problems. The acoustic forms of vocal emotions are often explicable with reference to the communicative functions they serve. An adaptationist approach to vocal emotions requires that we distinguish between evolved signals and byproduct cues, and understand vocal affect as a collection of multiple strategic communicative systems subject to the evolutionary dynamics described by signaling theory. We should expect variability across disparate societies in vocal emotion according to culturally evolved pragmatic rules, and universals in vocal production and perception to the extent that form–function relationships are present. Keywords emotion, evolution, signaling, vocal affect Emotional communication is central to social life for many ani- 2001; Pisanski, Cartei, McGettigan, Raine, & Reby, 2016; mals. Beginning with Darwin -

Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Paul Johnsgard Collection Papers in the Biological Sciences 1983 Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants" (1983). Paul Johnsgard Collection. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paul Johnsgard Collection by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. HYBRIDIZATION & ZOOGEOGRAPHIC PATTERNS IN PHEASANTS PAUL A. JOHNSGARD The purpose of this paper is to infonn members of the W.P.A. of an unusual scientific use of the extent and significance of hybridization among pheasants (tribe Phasianini in the proposed classification of Johnsgard~ 1973). This has occasionally occurred naturally, as for example between such locally sympatric species pairs as the kalij (Lophura leucol11elana) and the silver pheasant (L. nycthelnera), but usually occurs "'accidentally" in captive birds, especially in the absence of conspecific mates. Rarely has it been specifically planned for scientific purposes, such as for obtaining genetic, morphological, or biochemical information on hybrid haemoglobins (Brush. 1967), trans ferins (Crozier, 1967), or immunoelectrophoretic comparisons of blood sera (Sato, Ishi and HiraI, 1967). The literature has been summarized by Gray (1958), Delacour (1977), and Rutgers and Norris (1970). Some of these alleged hybrids, especially those not involving other Galliformes, were inadequately doculnented, and in a few cases such as a supposed hybrid between domestic fowl (Gallus gal/us) and the lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) can be discounted. -

Science News | December 19, 2009 Feature | Humans Wonder, Anybody Home?

FEATURE | HUMANS WONDER, ANYBODY HOME? To prevent Shania the octopus from becom- Humans wonder, ing bored, keepers at the National Aquarium in Washington, D.C., gave her a Mr. Potato Head filled with fish to snuggle. Researchers anybody are now looking beyond behavior into the brain for signs of awareness in birds and invertebrates. home? Brain structure and circuitry offer clues to consciousness in nonmammals By Susan Gaidos ne afternoon while participat except for the fact that Betty was a New ing in studies in a University Caledonian crow. of Oxford lab, Abel snatched Betty isn’t the only crow with such a hook away from Betty, leav conceptual ingenuity. Nor are crows the Oing her without a tool to complete a task. only members of the animal kingdom to Spying a piece of straight wire nearby, exhibit similar mental powers. Animals POST WASHINGTON THE she picked it up, bent one end into a can do all sorts of clever things: Studies EARY/ L ’ hook and used it to finish the job. Noth of chimpanzees, gorillas, dolphins and O ILL ing about this story was remarkable, birds have found that some can add, B 22 | SCIENCE NEWS | December 19, 2009 www.sciencenews.org FEATURE | HUMANS WONDER, ANYBODY HOME? subtract, create sentences, plan ahead objects in their visual field. “This raises or deceive others. the intriguing question whether con Brain-on-brain comparisons To carry out such tasks, these animals scious experience requires the specific In an effort to find signs of conscious- ness, scientists are identifying analo- must be drawing on past experiences and structure of human or primate brains,” gous structures (same coloring) among then using them along with immediate biologist Donald Griffin wrote inAnimal the brains of humans, birds, octopuses perceptions to make sense of it all. -

Book Reviews Edited by P

Book reviews Edited by P. Dann BANDER'S AID - A GUIDE TO AGEING AND species, plus the three identification keys, mainly of SEXING BUSH BIRDS bush species, although the supplement does contain de- by Ken Rogers, Annie Rogers, Danny Rogers with tails of seven waders. The species descriptions are very assistance from Brett Lane & Bruce Male comprehensive and detailed. They include male and fe- male plumages, as well as immature and juvenile 1986. A. Rogers; St. Andrews, Victoria. Pp. 138, b&w plumages where possible, and details of moult, ageing drawings 12,l map, many tables, 295 x 210 mm. and sexing. This hopefully will act as a spur to many Available from RAOU, $20 (posted). banders and ex-banders to extract information from BANDER'S AID - SUPPLEMENT NUMBER ONE their notebooks and help fill the gaps. by Ken Rogers, Annie Rogers and Danny Rogers The authors have done Australian ornithology a ser- vice by initiating this study. They admit these books are 1990. RAOU; Melbourne. Pp. 76, many tables, 205 x only a starting point and that a lot more data need to be 150 mm. Available from RAOU, $10 (posted). collected. However, if banders can rise to the occasion, These days it is pleasantly surprising to read bird books this approach of cooperative data gathering can lead to that present totally new information about Australian a major advance in our understanding of the regional birds. These two books do just that as the information differences in the morphology of Australian birds. It is they contain is not available from any other source. -

Going Beyond Just-So Stories Response to Commentary on Key on Fish Pain

Animal Sentience 2016.022: Response to Commentary on Key on Fish Pain Going beyond just-so stories Response to Commentary on Key on Fish Pain Brian Key School of Biomedical Sciences University of Queensland Abstract: Colloquial arguments for fish feeling pain are deeply rooted in anthropometric tendencies that confuse escape responses to noxious stimuli with evidence for consciousness. More developed arguments often rely on just-so stories of fish displaying complex behaviours as proof of consciousness. In response to commentaries on the idea that fish do not feel pain, I raise the need to go beyond just-so stories and to rigorously analyse the neural circuitry responsible for specific behaviours using new and emerging technologies in neuroscience. By deciphering the causal relationship between neural information processing and conscious behaviour, it should be possible to assess cogently the likelihood of whether a vertebrate species has the neural hardware necessary to — at least — support the feeling of pain. Brian Key [email protected] is Head of the Brain Growth and Regeneration Lab at the University of Queensland. He is dedicated to understanding the principles of stem cell biology, differentiation, axon guidance, plasticity, regeneration and development of the brain. http://www.uq.edu.au/sbms/staff/brian-key Just-so stories In this response to commentaries on the target article “Fish do not feel pain” (Key), I do not plan to interrogate either the putative behavioural evidence or the just-so stories previously proposed as supportive of fish feeling pain (Balcombe; Braithwaite & Droege; Broom; Brown; Dinets; Ng). These claims have been adequately addressed and refuted in recent literature (Key, 2015a and 2015b; Rose et al., 2014). -

Passerines: Perching Birds

3.9 Orders 9: Passerines – perching birds - Atlas of Birds uncorrected proofs 3.9 Atlas of Birds - Uncorrected proofs Copyrighted Material Passerines: Perching Birds he Passeriformes is by far the largest order of birds, comprising close to 6,000 P Size of order Cardinal virtues Insect-eating voyager Multi-purpose passerine Tspecies. Known loosely as “perching birds”, its members differ from other Number of species in order The Northern or Common Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) The Common Redstart (Phoenicurus phoenicurus) was The Common Magpie (Pica pica) belongs to the crow family orders in various fine anatomical details, and are themselves divided into suborders. Percentage of total bird species belongs to the cardinal family (Cardinalidae) of passerines. once thought to be a member of the thrush family (Corvidae), which includes many of the larger passerines. In simple terms, however, and with a few exceptions, passerines can be described Like the various tanagers, grosbeaks and other members (Turdidae), but is now known to belong to the Old World Like many crows, it is a generalist, with a robust bill adapted of this diverse group, it has a thick, strong bill adapted to flycatchers (Muscicapidae). Its narrow bill is adapted to to feeding on anything from small animals to eggs, carrion, as small birds that sing. feeding on seeds and fruit. Males, from whose vivid red eating insects, and like many insect-eaters that breed in insects, and grain. Crows are among the most intelligent of The word passerine derives from the Latin passer, for sparrow, and indeed a sparrow plumage the family is named, are much more colourful northern Europe and Asia, this species migrates to Sub- birds, and this species is the only non-mammal ever to have is a typical passerine. -

Download Listening Notes

The Tall Forests of South-East Australia. Morning - Massive eucalypts rise from the forest floor, their crowns spreading high overhead. We begin our forest journey in the coolness of pre-dawn. The air is humid, heavy with Many are of imposing size and great age. The oldest trees may have been mature long the scents of the forest. A small mountain stream flows through the undergrowth, before European people settled this continent. When timber cutters first entered gurgling softly. these forests, they found and felled the tallest trees ever known. The Mountain Ash that remain today are still the tallest hardwood trees, and the tallest flowering plants, Track 1: The Forest Awakens 10.20 in the world. First light dimly filters into the recesses of the forest. Eastern Yellow Robins, usually Below them, forming a luxurious understorey bathed in pools of sunlight, are a tangle the first birds calling, greet the dawn with their loud “Chaf, Chaf” and piping calls of shrubs and ferns. Where conditions are suitable, and fire has not intervened, a true (0:00), and also a soft scolding chatter (especially around 1:44). The cascading trills rainforest has developed; a cool emerald world closing out the sky above. Here tree of a Grey Fantail (0:19, 0:34, 0:52...) and the “chew-ee, chew-ee, chew-ee” of a Satin ferns, some 15 metres high and hundreds of years old, shade an open and moist forest Flycatcher (0:44) join in. floor with fallen logs covered by mosses, liverworts and fungi. A group of Kookaburras, particularly vocal at dawn, make contact and affirm territory We are in an ancient realm. -

A Novel Reinforcement Model of Birdsong Vocalization Learning

A Novel Reinforcement Model of Birdsong Vocalization Learning Kenji Doya Terrence J. Sejnowski ATR Human Infonnation Processing Howard Hughes Medical Institute Research Laboratories UCSD and Salk Institute, 2-2 Hikaridai, Seika, Kyoto 619-02, Japan San Diego, CA 92186-5800, USA Abstract Songbirds learn to imitate a tutor song through auditory and motor learn ing. We have developed a theoretical framework for song learning that accounts for response properties of neurons that have been observed in many of the nuclei that are involved in song learning. Specifically, we suggest that the anteriorforebrain pathway, which is not needed for song production in the adult but is essential for song acquisition, provides synaptic perturbations and adaptive evaluations for syllable vocalization learning. A computer model based on reinforcement learning was con structed that could replicate a real zebra finch song with 90% accuracy based on a spectrographic measure. The second generation of the bird song model replicated the tutor song with 96% accuracy. 1 INTRODUCTION Studies of motor pattern generation have generally focussed on innate motor behaviors that are genetically preprogrammed and fine-tuned by adaptive mechanisms (Harris-Warrick et al., 1992). Birdsong learning provides a favorable opportunity for investigating the neuronal mechanisms for the acquisition of complex motor patterns. Much is known about the neuroethology of bird song and its neuroanatomical substrate (see Nottebohm, 1991 and Doupe, 1993 for reviews), but relatively little is known about the overall system from a computational viewpoint. We propose a set of hypotheses for the functions of the brain nuclei in the song system and explore their computational strength in a model based on biological constraints.