Chapter Four Olivier Messiaen and the Albert's Lyrebird

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Papua New Guinea Huon Peninsula Extension 26Th June to 1St July 2018 (6 Days) Trip Report

Papua New Guinea Huon Peninsula Extension 26th June to 1st July 2018 (6 days) Trip Report Pesquet’s Parrots by Sue Wright Tour Leader: Adam Walleyn Rockjumper Birding Tours View more tours to Papua New Guinea Trip Report – RBL Papua New Guinea - Huon Peninsula Extension I 2018 2 Tour Summary This was our inaugural Huon Peninsula Extension. Most of the group started out with a quick flight from Moresby into Nadzab Airport. Upon arrival, we drove to our comfortable hotel on the outskirts of Lae City. After getting settled in, we set off on a short but very productive bird walk around the hotel’s expansive grounds. The best thing about the walk was how confiding the birds were –they are clearly not hunted much around here! Red-cheeked Parrot, Coconut Lorikeet, Orange-bellied Fruit Dove, Torresian Imperial Pigeon, White-bellied Cuckooshrike, Yellow-faced Myna, and Singing Starling all vied for our attention right in the parking lot. As we took a short wander, we added Hooded Butcherbird, New Guinea Friarbird and look-alike Brown Oriole, and Black and Olive-backed Sunbirds to our growing tally. A Buff-faced Pygmy Parrot zipped overhead providing just a quick view, but the highlight of the walk was clearly the Palm Cockatoo that sat out feeding contentedly on fruits – admittedly a bit of a surprise to find this species so close to a major urban centre! We were relieved when Sue had arrived and Pinon’s Imperial Pigeon by Markus Lilje joined us for dinner to complete the group! The real adventure began early the next morning, with a drive back to the airport where we were to board our flight into the Huon. -

A Little Flute Music: Mimicry, Memory, and Narrativity

Environmental Humanities, vol. 3, 2013, pp. 43-70 www.environmentalhumanities.org ISSN: 2201-1919 A Little Flute Music: Mimicry, Memory, and Narrativity Vicki Powys, Hollis Taylor and Carol Probets Powys: Independent scholar, Capertee Valley, New South Wales, Australia Taylor: Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia. Probets: Independent scholar, Katoomba, New South Wales, Australia. ABSTRACT A lyrebird chick was raised in captivity in the 1920s in Australia’s New England Tablelands, or so the story goes. The bird mimicked the sounds of the household’s flute player, learning two tunes and an ascending scale. When released back into the wild, his flute-like songs and timbre spread throughout the local lyrebird population. We count ourselves among those who admire the sonic achievements of this bioregion’s “flute lyrebirds.” These Superb Lyrebirds (Menura novaehollandiae) do indeed deliver an unusual and extraordinarily complex, flute-like territorial song, although often with a musical competence exceeding what a human flutist could achieve. In this paper, we engage with both the living and the dead across a wide-ranging cast of characters, linking up in the here and now and grasping a hand across the span of many years. Memory and narrativity are pertinent to the at times conflicting stories and reminiscences from archival and contemporary sources. Ultimately, accounts of “flute lyrebirds” speak to how meaning evolves in the tensions, boundaries, and interplay between knowledge and imagination. We conclude that this story exceeds containment, dispersed as it is across several fields of inquiry and a number of individual memories that go in and out of sync. -

Recommended Band Size List Page 1

Jun 00 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme - Recommended Band Size List Page 1 Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme Recommended Band Size List - Birds of Australia and its Territories Number 24 - May 2000 This list contains all extant bird species which have been recorded for Australia and its Territories, including Antarctica, Norfolk Island, Christmas Island and Cocos and Keeling Islands, with their respective RAOU numbers and band sizes as recommended by the Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme. The list is in two parts: Part 1 is in taxonomic order, based on information in "The Taxonomy and Species of Birds of Australia and its Territories" (1994) by Leslie Christidis and Walter E. Boles, RAOU Monograph 2, RAOU, Melbourne, for non-passerines; and “The Directory of Australian Birds: Passerines” (1999) by R. Schodde and I.J. Mason, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, for passerines. Part 2 is in alphabetic order of common names. The lists include sub-species where these are listed on the Census of Australian Vertebrate Species (CAVS version 8.1, 1994). CHOOSING THE CORRECT BAND Selecting the appropriate band to use combines several factors, including the species to be banded, variability within the species, growth characteristics of the species, and band design. The following list recommends band sizes and metals based on reports from banders, compiled over the life of the ABBBS. For most species, the recommended sizes have been used on substantial numbers of birds. For some species, relatively few individuals have been banded and the size is listed with a question mark. In still other species, too few birds have been banded to justify a size recommendation and none is made. -

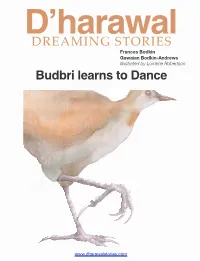

Budbri Learns to Dance DREAMING STORIES

D’harawal DREAMING STORIES Frances Bodkin Gawaian Bodkin-Andrews illustrated by Lorraine Robertson Budbri learns to Dance www.dharawalstories.com Budbri Learns to Dance Frances Bodkin Gawaian Bodkin-Andrews illustrated by Lorraine Robertson www.dharawalstories.com Foreword Throughout the past two hundred years, society has come to regard the Koori Dreaming stories as something akin to the fairy stories they were told as children. However, for thousands upon thousands of years, the stories in this book were used as a teaching tool to impart to the youngest members of the clans the laws which governed the cultural behaviour of clan members. The successive attempts to destroy the Koori culture and assimilate The People into the Euro-centric population were unsuccessful, and the Dreaming Stories were able to continue in their dis- guise as charming legends where animals became the heroes and the heroines. Historians and anthropologists have studied the Koori culture since they first arrived on this continent, and have come to the conclusion that the D’harawal culture is dead. Of, course, this has been done without reference to the descendants of that culture, and without even asking the proper questions. The D’harawal culture is not dead, it is a strong, living, vital culture of the Sydney and South Coast re- gions that just had to go underground for a while to be able to survive. Now that the right questions have been asked, we have the key to unlock a vast wealth of knowledge of this part of the country in which we live. It is difficult to explain to a society based on commerce fuelled by the profit motive, that D’harawal cul- ture is not based on the ownership of tangible things like land and dwellings and possessions, but it does have a very strong sense of ownership of information. -

Lyrebird Tales

Lyrebird Tales Volume 28 Number 3 September 2019 A TRIP TO THE U.K. 2019 (OR; THOUGHTS TO MULL OVER ) By Doug Pocock Nuthatch photo © Alan Spellman Our bird list started with a Great Heron on the river and then Blue, Long-tailed and Great Tits, Nuthatch, Chaffinch and Rock Wren. We knew we were back in the UK! At the head of the gorge was a small weir and many Sand Martins were feeding on the insects. We were impressed by the local authorities who had installed a large wooden board against a bank of earth and had drilled Martin size holes to enable the birds to breed. Continued on page 2 Contents 1-3. Trip to the UK by Doug Pocock 4. Toora, Gippsland by Warren Cousins 5-6. Challenge for high-rise real estate by Valerie Fowler 6. Interesting sightings. Whose feathers? Committee Looking over Loch na Keal, Mull photo © Alan Spellman 7. Proposed outing to Mud Islands notice. We left home on May 27th and flew one stop to Edinburgh. Lillydale Lake update. Birdlife Yarra Valley camp notice. Here we picked up our hire car and were off. In the past we The one that nearly got away. found it best to pre-book accommodation so we headed for 8-9. Reports of Meetings and Outings New Lanark mill town. This was a fascinating place to stay, built by Richard Owen, an early reformer, as an enlightened 10. Calendar of Events place of employment. For instance he did not employ children under the age of ten instead he provided schooling for them. -

Bird Abundances in Primary and Secondary Growths in Papua New Guinea: a Preliminary Assessment

Mongabay.com Open Access Journal - Tropical Conservation Science Vol.3 (4):373-388, 2010 Research Article Bird abundances in primary and secondary growths in Papua New Guinea: a preliminary assessment Kateřina Tvardíková1 1 Department of Zoology, Faculty of Biological Science, University of South Bohemia, Branišovská 31, CZ- 370 05 České Budějovice. Email: <[email protected] Abstract Papua New Guinea is the third largest remaining area of tropical forest after the Amazon and Congo basins. However, the growing intensity of large-scale slash-and-burn agriculture and logging call for conservation research to assess how local people´s traditional land-use practices result in conservation of local biodiversity, of which a species-rich and diverse component is the avian community. With this in mind, I conducted a preliminary survey of birds in small-scale secondary plots and in adjacent primary forest in Wanang Conservation Area in Papua New Guinea. I used mist-netting, point counts, and transect walks to compare the bird communities of 7-year-old secondary growth, and neighboring primary forest. The preliminary survey lasted 10 days and was conducted during the dry season (July) of 2008. I found no significant differences in summed bird abundances between forest types. However, species richness was higher in primary forest (98 species) than in secondary (78 species). The response of individual feeding guilds was also variable. Two habitats differed mainly in presence of canopy frugivores, which were more abundant (more than 80%) in primary than in secondary forests. A large difference (70%) was found also in understory and mid-story insectivores. Species occurring mainly in secondary forest were Hooded Butcherbird (Cracticus cassicus), Brown Oriole (Oriolus szalayi), and Helmeted Friarbird (Philemon buceroides). -

Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Paul Johnsgard Collection Papers in the Biological Sciences 1983 Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants" (1983). Paul Johnsgard Collection. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paul Johnsgard Collection by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. HYBRIDIZATION & ZOOGEOGRAPHIC PATTERNS IN PHEASANTS PAUL A. JOHNSGARD The purpose of this paper is to infonn members of the W.P.A. of an unusual scientific use of the extent and significance of hybridization among pheasants (tribe Phasianini in the proposed classification of Johnsgard~ 1973). This has occasionally occurred naturally, as for example between such locally sympatric species pairs as the kalij (Lophura leucol11elana) and the silver pheasant (L. nycthelnera), but usually occurs "'accidentally" in captive birds, especially in the absence of conspecific mates. Rarely has it been specifically planned for scientific purposes, such as for obtaining genetic, morphological, or biochemical information on hybrid haemoglobins (Brush. 1967), trans ferins (Crozier, 1967), or immunoelectrophoretic comparisons of blood sera (Sato, Ishi and HiraI, 1967). The literature has been summarized by Gray (1958), Delacour (1977), and Rutgers and Norris (1970). Some of these alleged hybrids, especially those not involving other Galliformes, were inadequately doculnented, and in a few cases such as a supposed hybrid between domestic fowl (Gallus gal/us) and the lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) can be discounted. -

Book Reviews Edited by P

Book reviews Edited by P. Dann BANDER'S AID - A GUIDE TO AGEING AND species, plus the three identification keys, mainly of SEXING BUSH BIRDS bush species, although the supplement does contain de- by Ken Rogers, Annie Rogers, Danny Rogers with tails of seven waders. The species descriptions are very assistance from Brett Lane & Bruce Male comprehensive and detailed. They include male and fe- male plumages, as well as immature and juvenile 1986. A. Rogers; St. Andrews, Victoria. Pp. 138, b&w plumages where possible, and details of moult, ageing drawings 12,l map, many tables, 295 x 210 mm. and sexing. This hopefully will act as a spur to many Available from RAOU, $20 (posted). banders and ex-banders to extract information from BANDER'S AID - SUPPLEMENT NUMBER ONE their notebooks and help fill the gaps. by Ken Rogers, Annie Rogers and Danny Rogers The authors have done Australian ornithology a ser- vice by initiating this study. They admit these books are 1990. RAOU; Melbourne. Pp. 76, many tables, 205 x only a starting point and that a lot more data need to be 150 mm. Available from RAOU, $10 (posted). collected. However, if banders can rise to the occasion, These days it is pleasantly surprising to read bird books this approach of cooperative data gathering can lead to that present totally new information about Australian a major advance in our understanding of the regional birds. These two books do just that as the information differences in the morphology of Australian birds. It is they contain is not available from any other source. -

Passerines: Perching Birds

3.9 Orders 9: Passerines – perching birds - Atlas of Birds uncorrected proofs 3.9 Atlas of Birds - Uncorrected proofs Copyrighted Material Passerines: Perching Birds he Passeriformes is by far the largest order of birds, comprising close to 6,000 P Size of order Cardinal virtues Insect-eating voyager Multi-purpose passerine Tspecies. Known loosely as “perching birds”, its members differ from other Number of species in order The Northern or Common Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) The Common Redstart (Phoenicurus phoenicurus) was The Common Magpie (Pica pica) belongs to the crow family orders in various fine anatomical details, and are themselves divided into suborders. Percentage of total bird species belongs to the cardinal family (Cardinalidae) of passerines. once thought to be a member of the thrush family (Corvidae), which includes many of the larger passerines. In simple terms, however, and with a few exceptions, passerines can be described Like the various tanagers, grosbeaks and other members (Turdidae), but is now known to belong to the Old World Like many crows, it is a generalist, with a robust bill adapted of this diverse group, it has a thick, strong bill adapted to flycatchers (Muscicapidae). Its narrow bill is adapted to to feeding on anything from small animals to eggs, carrion, as small birds that sing. feeding on seeds and fruit. Males, from whose vivid red eating insects, and like many insect-eaters that breed in insects, and grain. Crows are among the most intelligent of The word passerine derives from the Latin passer, for sparrow, and indeed a sparrow plumage the family is named, are much more colourful northern Europe and Asia, this species migrates to Sub- birds, and this species is the only non-mammal ever to have is a typical passerine. -

Download Listening Notes

The Tall Forests of South-East Australia. Morning - Massive eucalypts rise from the forest floor, their crowns spreading high overhead. We begin our forest journey in the coolness of pre-dawn. The air is humid, heavy with Many are of imposing size and great age. The oldest trees may have been mature long the scents of the forest. A small mountain stream flows through the undergrowth, before European people settled this continent. When timber cutters first entered gurgling softly. these forests, they found and felled the tallest trees ever known. The Mountain Ash that remain today are still the tallest hardwood trees, and the tallest flowering plants, Track 1: The Forest Awakens 10.20 in the world. First light dimly filters into the recesses of the forest. Eastern Yellow Robins, usually Below them, forming a luxurious understorey bathed in pools of sunlight, are a tangle the first birds calling, greet the dawn with their loud “Chaf, Chaf” and piping calls of shrubs and ferns. Where conditions are suitable, and fire has not intervened, a true (0:00), and also a soft scolding chatter (especially around 1:44). The cascading trills rainforest has developed; a cool emerald world closing out the sky above. Here tree of a Grey Fantail (0:19, 0:34, 0:52...) and the “chew-ee, chew-ee, chew-ee” of a Satin ferns, some 15 metres high and hundreds of years old, shade an open and moist forest Flycatcher (0:44) join in. floor with fallen logs covered by mosses, liverworts and fungi. A group of Kookaburras, particularly vocal at dawn, make contact and affirm territory We are in an ancient realm. -

West Papua Expedition

The fabulous Spangled Kookaburra was one of the many highlights (Mark Van Beirs) WEST PAPUA EXPEDITION 22/28 OCTOBER – 10 NOVEMBER 2019 LEADER: MARK VAN BEIRS 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: West Papua Expedition www.birdquest-tours.com The cracking Kofiau Paradise Kingfisher posed ever so well (Mark Van Beirs) This unusual trip was set up to fill in some of the remaining gaps in the Birdquest New Guinea lifelist, so the plan was to visit several hard to reach venues in West Papua. The pre-trip was aiming to climb to the top of 2 BirdQuest Tour Report: West Papua Expedition www.birdquest-tours.com Mount Trikora in the Snow Mountains, but because of recent rioting and civil unrest (whereby several dozen people had been killed), access to the town of Wamena was totally denied to foreign visitors by the authorities. So, sadly, no Snow Mountain Robin… We did manage to visit the famous Wasur National Park, which produced the fantastic Spangled Kookaburra and Grey-crowned and Black Mannikins (all Birdquest lifers) and we reached the island of Kofiau, where the fabulous Kofiau Paradise Kingfisher and the modestly- plumaged Kofiau Monarch (two more Birdquest lifers) showed extremely well. The fabulous lowland rainforest site of Malagufuk gave us a long list of exquisite species amongst which a truly impressive Northern Cassowary, a cute Wallace’s Owlet-nightjar, a sublime Papuan Hawk-Owl and a tremendous Red- breasted Paradise Kingfisher stood out. Kingfishers especially performed extremely well on this tour as we saw no fewer than 15 species, including marvels like Hook-billed, Common Paradise, Blue-black, Beach, Yellow-billed and Papuan Dwarf Kingfishers and Blue-winged and Rufous-bellied Kookaburras. -

WVCP Bird Paper

Mongabay.com Open Access Journal - Tropical Conservation Science Vol.4 (3):317-348, 2011 Research Article Bird communities of the lower Waria Valley, Morobe Province, Papua New Guinea: a comparison between habitat types 1* 2,3 1,4 Jeff Dawson , Craig Turner , Oscar Pileng , Andrew Farmer1, Cara McGary1, Chris Walsh1, Alexia Tamblyn2 and Cossey Yosi5 1Coral Cay Conservation, 1st Floor Block, 1 Elizabeth House, 39 York Road, London SW1 7NQ UK 2Previous address: Jaquelin Fisher Associates, 4 Yukon Road, London SW12 9PU, UK 3Current address: Zoological Society of London, Regents Park, London NW1 4RY, UK 4FORCERT, Walindi Nature Centre, Talasea Highway, West New Britain Province, Papua New Guinea 5Papua New Guinea Forest Research Institute, PO Box 314, Lae, Morobe Province, Papua New Guinea *Correspondence: Jeff Dawson < [email protected]> Abstract From June, 2007, to February, 2009, the Waria Valley Community Conservation and Sustainable Livelihoods Project (WVCP) completed an inventory survey of the birds of the lower Waria Valley, Morobe Province, Papua New Guinea. Four land use types -- agricultural, secondary forest edge, primary forest edge and primary forest -- were surveyed using Mackinnon list surveys. In total, 125 species representing 43 families were identified, of which 54 (43.2%) are endemic to the islands of New Guinea and the Bismark Archipelago. The avifauna of primary forest edge and primary forest was more species rich and diverse than that of agricultural habitats. Agricultural habitats also differed significantly in both overall community composition and some aspects of guild composition compared to all three forested habitats. Nectarivores and insectivore-frugivores formed a significantly larger proportion of species in agricultural habitats, whereas obligate frugivores formed a significantly greater proportion in forested habitats.