Linguistic Motivation, Dramatic Language and Glasgow-Inflected Scots in Edwin Morgan's Version of Cyrano De Bergerac (1992)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

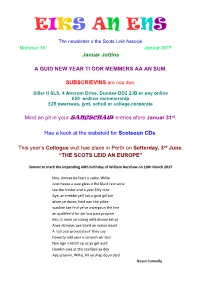

EIKS an ENS Nummer 10

EIKS AN ENS The newsletter o the Scots Leid Associe Nummer 10 Januar 2017 Januar Jottins A GUID NEW YEAR TI OOR MEMMERS AA AN SUM. SUBSCRIEVINS are nou due. Siller ti SLS, 4 Ancrum Drive, Dundee DD2 2JB or pey online £20 ordinar memmership £25 owerseas, jynt, schuil or college,corporate Mind an pit in your entries afore Januar 31st. Hae a keek at the wabsteid for Scotsoun CDs. This year’s Collogue wull hae place in Perth on Setterday, 3rd June. “THE SCOTS LEID AN EUROPE” Sonnet to mark the impending 60th birthday of William Hershaw on 19th March 2017 Nou, dinnae be feart o saxty, Willie Juist heeze a wee gless o the bluid reid wine tae the hinder end o year fifty nine Aye, an mebbe ye'll tak a guid gill tae afore ye dover, heid oan the pillae wauken tae find ye’ve owergaun the line an qualifee’d for yer bus pass propine Ken, it maks ye strang whit disnae kill ye Ance domine, aye baird an makar bauld A ‘cultural provocateur’ they say Fowerty odd year o scrievin wir leid Nae sign o lettin up as ye get auld Howkin awa at the coalface aa dey Aye screivin, Willie, till ye drap doun deid Kevin Connelly Burns’ Hamecomin When taverns stert tae stowe wi folk, Bit tae oor tale. Rab’s here as guest, An warkers thraw aff labour’s yoke, Tae handsel this by-ornar fest – As simmer days are waxin lang, Twa hunnert years an fifty’s passed An couthie chiels brak intae sang; Syne he blew in on Janwar’s blast. -

Artymiuk, Anne

UHI Thesis - pdf download summary Today's No Ground to Stand Upon A Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Artymiuk, Anne DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (AWARDED BY OU/ABERDEEN) Award date: 2019 Awarding institution: The University of Edinburgh Link URL to thesis in UHI Research Database General rights and useage policy Copyright,IP and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the author, users must recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement, or without prior permission from the author. Users may download and print one copy of any thesis from the UHI Research Database for the not-for-profit purpose of private study or research on the condition that: 1) The full text is not changed in any way 2) If citing, a bibliographic link is made to the metadata record on the the UHI Research Database 3) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 4) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that any data within this document represents a breach of copyright, confidence or data protection please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 ‘Today’s No Ground to Stand Upon’: a Study of the Life and Poetry of George Campbell Hay Anne Artymiuk M.A. -

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Migrating Minds

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Volume 5: Issue 1 Migrating Minds AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies, University of Aberdeen JOURNAL OF IRISH AND SCOTTISH STUDIES Volume 5, Issue 1 Autumn 2011 Migrating Minds Published by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen in association with The universities of the The Irish-Scottish Academic Initiative ISSN 1753-2396 Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham and Eastbourne Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies General Editor: Cairns Craig Issue Editor: Paul Shanks Associate Editor: Michael Brown Editorial Advisory Board: Fran Brearton, Queen’s University, Belfast Eleanor Bell, University of Strathclyde Ewen Cameron, University of Edinburgh Sean Connolly, Queen’s University, Belfast Patrick Crotty, University of Aberdeen David Dickson, Trinity College, Dublin T. M. Devine, University of Edinburgh David Dumville, University of Aberdeen Aaron Kelly, University of Edinburgh Edna Longley, Queen’s University, Belfast Peter Mackay, Queen’s University, Belfast Shane Alcobia-Murphy, University of Aberdeen Ian Campbell Ross, Trinity College, Dublin Graham Walker, Queen’s University, Belfast International Advisory Board: Don Akenson, Queen’s University, Kingston Tom Brooking, University of Otago Keith Dixon, Université Lumière Lyon 2 Marjorie Howes, Boston College H. Gustav Klaus, University of Rostock Peter Kuch, University of Otago Graeme Morton, University of Guelph Brad Patterson, Victoria University, Wellington Matthew Wickman, Brigham Young David Wilson, University of Toronto The Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies is a peer reviewed journal published twice yearly in autumn and spring by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen. -

Representations of Scotland in Edwin Morgan's Poetry

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 Representations of Scotland in Edwin Morgan's poetry Theresa Fernandez Mendoza-Kovich Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Mendoza-Kovich, Theresa Fernandez, "Representations of Scotland in Edwin Morgan's poetry" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2157. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2157 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REPRESENTATIONS OF SCOTLAND IN EDWIN MORGAN'S POETRY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition by Theresa Fernandez Mendoza-Kovich September 2002 REPRESENTATIONS OF SCOTLAND IN EDWIN MORGAN'S POETRY A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Theresa Fernandez Mendoza-Kovich September 2002 Approved by: Renee PrqSon, Chair, English Date Margarep Doane Cyrrchia Cotter ABSTRACT This thesis is an examination of the poetry of Edwin Morgan. It is a cultural analysis of Morgan's poetry as representation of the Scottish people. ' Morgan's poetry represents the Scottish people as determined and persistent in dealing with life's adversities while maintaining hope in a better future This hope, according to Morgan, is largely associated with the advent of technology and the more modern landscape of his native Glasgow. -

Jackie Kay, CBE, Poet Laureate of Scotland 175Th Anniversary Honorees the Makar’S Medal

Jackie Kay, CBE, Poet Laureate of Scotland 175th Anniversary Honorees The Makar’s Medal The Chicago Scots have created a new award, the Makar’s Medal, to commemorate their 175th anniversary as the oldest nonprofit in Illinois. The Makar’s Medal will be awarded every five years to the seated Scots Makar – the poet laureate of Scotland. The inaugural recipient of the Makar’s Medal is Jackie Kay, a critically acclaimed poet, playwright and novelist. Jackie was appointed the third Scots Makar in March 2016. She is considered a poet of the people and the literary figure reframing Scottishness today. Photo by Mary McCartney Jackie was born in Edinburgh in 1961 to a Scottish mother and Nigerian father. She was adopted as a baby by a white Scottish couple, Helen and John Kay who also adopted her brother two years earlier and grew up in a suburb of Glasgow. Her memoir, Red Dust Road published in 2010 was awarded the prestigious Scottish Book of the Year, the London Book Award, and was shortlisted for the Jr. Ackerley prize. It was also one of 20 books to be selected for World Book Night in 2013. Her first collection of poetry The Adoption Papers won the Forward prize, a Saltire prize and a Scottish Arts Council prize. Another early poetry collection Fiere was shortlisted for the Costa award and her novel Trumpet won the Guardian Fiction Award and was shortlisted for the Impac award. Jackie was awarded a CBE in 2019, and made a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2002. -

"Dae Scotsmen Dream O 'Lectric Leids?" Robert Crawford's Cyborg Scotland

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 "Dae Scotsmen Dream o 'lectric Leids?" Robert Crawford's Cyborg Scotland Alexander Burke Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/3272 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i © Alexander P. Burke 2013 All Rights Reserved i “Dae Scotsmen Dream o ‘lectric Leids?” Robert Crawford’s Cyborg Scotland A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English at Virginia Commonwealth University By Alexander Powell Burke Bachelor of Arts in English, Virginia Commonwealth University May 2011 Director: Dr. David Latané Associate Chair, Department of English Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia December, 2013 ii Acknowledgment I am forever indebted to the VCU English Department for providing me with a challenging and engaging education, and its faculty for making that experience enjoyable. It is difficult to single out only several among my professors, but I would like to acknowledge David Wojahn and Dr. Marcel Cornis-Pope for not only sitting on my thesis committee and giving me wonderful advice that I probably could have followed more closely, but for their role years prior of inspiring me to further pursue poetry and theory, respectively. -

Imagining Scotland

Imagining Scotland National Self-Depiction in Sir Walter Scott's Waverley , Lewis Grassic Gibbon's Sunset Song , Irvine Welsh's Trainspotting and Alasdair Gray's Lanark Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät IV (Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaften) der Universität Regensburg vorgelegt von Christian Kucznierz Mühlfeldstr. 12 93083 Obertraubling 2008 Regensburg 2009 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Rainer Emig Zweitgutachter: PD Dr. Anne-Julia Zwierlein Acknowledgements In the six years it took to finish this study, I was working simultaneously on my professional career outside of the university. It was Prof. Dr. Rainer Emig's constant encouragement which helped me not to lose sight of the aim I was pursuing in all those years. I would like to thank him for giving me the chance to start my dissertation, for his support, his valuable advice and the fact that I could call on him at any time. Furthermore, I would like to thank PD Dr. Anne-Julia Zwierlein, who on rather short notice agreed to supervise my work, and whose ideas helped to give my thesis the necessary final touches. I would also like to thank my wife, Sandra, and my family, who have been patient enough to understand that my weekends, holidays and evenings after work were mostly busy – and that my mind much too often strayed from important issues. Without their support and understanding, this thesis would never have come into existence. Obertraubling, 2009 Table of Contents page 1. How does Scotland imagine itself? 5 2. Imagi-Nation: Literature and Self-Depiction 8 2.1. The Printed Word, Community and Identity 9 2.2. -

Edwin Morgan's Early Concrete Poetry

ELEANOR BELL Experimenting with the Verbivocovisual: Edwin Morgan's Early Concrete Poetry In The Order of Things: An Anthology of Scottish Sound, Pattern and Goncrete Poems, Ken Cockburn and Alec Finlay suggest that with the advent of con- crete poetry, 'Scotland connected to an international avant-garde movement in a manner barely conceivable today'. The 'classic phase' of concrete poetry in Scotiand, they note, begins around 1962, and, referencing Stephen Scobie, they point out that it should probably be regarded as an experiment in late modernism in its concerns with 'self-refiexiveness, juxtaposition and simultanism'.^ Some of the chief concerns of concrete poetry were therefore to expand upon the conceptual possibilities of poetry itself, instüling it with a new energy which could then radiate off the page, or the alternative medium on which it was presented. Both Edwin Morgan and Ian Hamilton Finlay were instantly drawn to these contrasts between the word, its verbal utterance and its overaU visual impact (or, as termed in Joyce's Finnegans Wake, its 'verbivocovisual presentements', which the Brazüian Noigandres later picked up on). Although going on to become the form's main pro- ponents within Scotiand, Morgan and Finlay recognised from early on that its Scottish reception most likely be frosty (with Hugh MacDiarmid famously asserting that 'these spatial arrangements of isolated letters and geo- metricaüy placed phrases, etc. have nothing whatever to do with poetry — any more than mud pies can be caüed architecture').^ Both poets none- theless entered into correspondence with key pioneering practitioners across the globe, and were united in their defence of the potential and legitimacy of the form. -

Jackie Kay Dates: 1978 - 1982 Role(S): Undergraduate Honorary Doctorate 2000

SURSA University of Stirling Stirling FK9 4LA SURSA [email protected] www.sursa.org.uk Interviewee: Jackie Kay Dates: 1978 - 1982 Role(s): Undergraduate Honorary doctorate 2000 Interview summary: Summary of content; with time (min:secs) 00:32 JK chose to study at Stirling because she liked the semester system; the fact that no early decision had to be taken about the degree programme and it was possible to study English with other subjects; there were courses in American poetry and novels. Compared to other universities there was freedom of choice. Stirling was close enough to her home in Glasgow and had a beautiful campus. She was only 17; she liked the sense of family provided by the University and the English Department. She took a course on the Indian novel in English and discovered that she could travel while sitting still. 02:30 She found her first year exciting; she was invited to select a poem for a tutorial and chose one about adoption by Anne Sexton. She valued the individual attention she was given; Rebecca and Russell Dobash in the Sociology Department tried to persuade her to focus on Sociology and she also studied History and Spanish but eventually took a single honours degree in English. 04:15 JK became aware of her multiple personalities and a widening of the self. She became politically active, joining the Gay Society, the Women’s Collective, Rock against Racism and the Anti-Nazi League. She formed lifelong friendships. She met other black people for almost the first time. There were 40 black students in a student population of 3000 at the University; they shared a camaraderie, acknowledging each other when they met on campus. -

Scots Verse Translation and the Second-Generation Scottish Renaissance

Sanderson, Stewart (2016) Our own language: Scots verse translation and the second-generation Scottish renaissance. PhD thesis https://theses.gla.ac.uk/7541/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Our Own Language: Scots Verse Translation and the Second-Generation Scottish Renaissance Stewart Sanderson Kepand na Sudroun bot our awyn langage Gavin Douglas, Eneados, Prologue 1.111 Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Critical Studies College of Arts University of Glasgow September 2015 Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................... 2 Abstract .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction: Verse Translation and the Modern Scottish Renaissance ........................................ -

Oral Tradition

_____________________________________________________________ Volume 1 October 1986 Number 3 _____________________________________________________________ Editor Editorial Assistants John Miles Foley Lee Edgar Tyler Juris Dilevko Patrick Gonder Nancy Hadfield Slavica Publishers, Inc. For a complete catalog of books from Slavica, with prices and ordering information, write to: Slavica Publishers, Inc. P.O. Box 14388 Columbus, Ohio 43214 ISSN: 0883-5365 Each contribution copyright (c) 1986 by its author. All rights reserved. The editor and the publisher assume no responsibility for statements of fact or opinion by the authors. Oral Tradition seeks to provide a comparative and interdisciplinary focus for studies in oral literature and related fields by publishing research and scholarship on the creation, transmission, and interpretation of all forms of oral traditional expression. As well as essays treating certifiably oral traditions, OT presents investigations of the relationships between oral and written traditions, as well as brief accounts of important fieldwork, a Symposium section (in which scholars may reply at some length to prior essays), review articles, occasional transcriptions and translations of oral texts, a digest of work in progress, and a regular column for notices of conferences and other matters of interest. In addition, occasional issues will include an ongoing annotated bibliography of relevant research and the annual Albert Lord and Milman Parry Lectures on Oral Tradition. OT welcomes contributions on all oral literatures, on all literatures directly influenced by oral traditions, and on non-literary oral traditions. Submissions must follow the list-of reference format (style sheet available on request) and must be accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope for return or for mailing of proofs; all quotations of primary materials must be made in the original language(s) with following English translations.