The Controversy Over the AMS Publishing Original Investigations Steve Batterson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S0002-9904-1917-02959-X.Pdf

1917.] EMORY McCLINTOCK. 353 £ = *(*), * = *«). It is clear that corresponding to any point w in the vicinity of f(zo) the function z = ^(£) furnishes n values of z. Also the form of ^(£) would depend on the particular circle chosen, but one form may be transformed into any other by replacing £ by the product of £ and the appropriate nth root of unity. UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO. EMORY McCLINTOCK. BUT few members of the American Mathematical Society at the present time appreciate the magnitude of the services rendered by its former president, Emory McClintock, who died July 10, 1916. He was born September 19, 1840, at Carlisle, Pa. His father was the Rev. John McClintock, a learned Methodist Episcopal clergyman, for a time professor of mathematics, Latin, and Greek in Dickinson College, and during the Civil War chaplain of the American Chapel in Paris. He is perhaps best known as the author, with another, of a " Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature." McClintock went to school for the first time at the age of thirteen, and a year later entered the freshman year of Dickin son College. In 1856, when his father left Dickinson College for New York, he entered Yale, and in 1857 he entered Colum bia as a member of the class of 1859. His remarkable ability excited the admiration of his teachers, Professors Charles Davies and William Guy Peck. In April, 1859 in order to meet an emergency caused by the illness of a member of the teaching staff, he was graduated and appointed tutor in mathe matics. Soon afterwards his father took charge of the Ameri can Chapel in Paris, and in 1860 McClintock resigned his position at Columbia to go abroad. -

Pursuit of Genius: Flexner, Einstein, and the Early Faculty at the Institute

i i i i PURSUIT OF GENIUS i i i i i i i i PURSUIT OF GENIUS Flexner, Einstein,and the Early Faculty at the Institute for Advanced Study Steve Batterson Emory University A K Peters, Ltd. Natick, Massachusetts i i i i i i i i Editorial, Sales, and Customer Service Office A K Peters, Ltd. 5 Commonwealth Road, Suite 2C Natick, MA 01760 www.akpeters.com Copyright ⃝c 2006 by A K Peters, Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or utilized in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy- ing, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Batterson, Steve, 1950– Pursuit of genius : Flexner, Einstein, and the early faculty at the Institute for Advanced Study / Steve Batterson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 13: 978-1-56881-259-5 (alk. paper) ISBN 10: 1-56881-259-0 (alk. paper) 1. Mathematics–Study and teaching (Higher)–New Jersey–Princeton–History. 2. Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, N.J.). School of Mathematics–History. 3. Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton, N.J.). School of Mathematics–Faculty. I Title. QA13.5.N383 I583 2006 510.7’0749652--dc22 2005057416 Cover Photographs: Front cover: Clockwise from upper left: Hermann Weyl (1930s, cour- tesy of Nina Weyl), James Alexander (from the Archives of the Institute for Advanced Study), Marston Morse (photo courtesy of the American Mathematical Society), Albert Einstein (1932, The New York Times), John von Neumann (courtesy of Marina von Neumann Whitman), Oswald Veblen (early 1930s, from the Archives of the Institute for Advanced Study). -

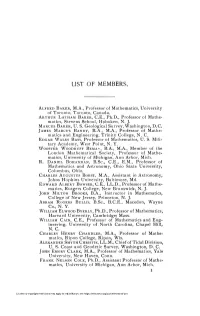

List of Members

LIST OF MEMBERS, ALFRED BAKER, M.A., Professor of Mathematics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada. ARTHUR LATHAM BAKER, C.E., Ph.D., Professor of Mathe matics, Stevens School, Hpboken., N. J. MARCUS BAKER, U. S. Geological Survey, Washington, D.C. JAMES MARCUS BANDY, B.A., M.A., Professor of Mathe matics and Engineering, Trinit)^ College, N. C. EDGAR WALES BASS, Professor of Mathematics, U. S. Mili tary Academy, West Point, N. Y. WOOSTER WOODRUFF BEMAN, B.A., M.A., Member of the London Mathematical Society, Professor of Mathe matics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. R. DANIEL BOHANNAN, B.Sc, CE., E.M., Professor of Mathematics and Astronomy, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. CHARLES AUGUSTUS BORST, M.A., Assistant in Astronomy, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Md. EDWARD ALBERT BOWSER, CE., LL.D., Professor of Mathe matics, Rutgers College, New Brunswick, N. J. JOHN MILTON BROOKS, B.A., Instructor in Mathematics, College of New Jersey, Princeton, N. J. ABRAM ROGERS BULLIS, B.SC, B.C.E., Macedon, Wayne Co., N. Y. WILLIAM ELWOOD BYERLY, Ph.D., Professor of Mathematics, Harvard University, Cambridge*, Mass. WILLIAM CAIN, C.E., Professor of Mathematics and Eng ineering, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N. C. CHARLES HENRY CHANDLER, M.A., Professor of Mathe matics, Ripon College, Ripon, Wis. ALEXANDER SMYTH CHRISTIE, LL.M., Chief of Tidal Division, U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, Washington, D. C. JOHN EMORY CLARK, M.A., Professor of Mathematics, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. FRANK NELSON COLE, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Mathe matics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. -

A Century of Mathematics in America, Peter Duren Et Ai., (Eds.), Vol

Garrett Birkhoff has had a lifelong connection with Harvard mathematics. He was an infant when his father, the famous mathematician G. D. Birkhoff, joined the Harvard faculty. He has had a long academic career at Harvard: A.B. in 1932, Society of Fellows in 1933-1936, and a faculty appointmentfrom 1936 until his retirement in 1981. His research has ranged widely through alge bra, lattice theory, hydrodynamics, differential equations, scientific computing, and history of mathematics. Among his many publications are books on lattice theory and hydrodynamics, and the pioneering textbook A Survey of Modern Algebra, written jointly with S. Mac Lane. He has served as president ofSIAM and is a member of the National Academy of Sciences. Mathematics at Harvard, 1836-1944 GARRETT BIRKHOFF O. OUTLINE As my contribution to the history of mathematics in America, I decided to write a connected account of mathematical activity at Harvard from 1836 (Harvard's bicentennial) to the present day. During that time, many mathe maticians at Harvard have tried to respond constructively to the challenges and opportunities confronting them in a rapidly changing world. This essay reviews what might be called the indigenous period, lasting through World War II, during which most members of the Harvard mathe matical faculty had also studied there. Indeed, as will be explained in §§ 1-3 below, mathematical activity at Harvard was dominated by Benjamin Peirce and his students in the first half of this period. Then, from 1890 until around 1920, while our country was becoming a great power economically, basic mathematical research of high quality, mostly in traditional areas of analysis and theoretical celestial mechanics, was carried on by several faculty members. -

A History of Mathematics in America Before 1900.Pdf

THE BOOK WAS DRENCHED 00 S< OU_1 60514 > CD CO THE CARUS MATHEMATICAL MONOGRAPHS Published by THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Publication Committee GILBERT AMES BLISS DAVID RAYMOND CURTISS AUBREY JOHN KEMPNER HERBERT ELLSWORTH SLAUGHT CARUS MATHEMATICAL MONOGRAPHS are an expression of THEthe desire of Mrs. Mary Hegeler Carus, and of her son, Dr. Edward H. Carus, to contribute to the dissemination of mathe- matical knowledge by making accessible at nominal cost a series of expository presenta- tions of the best thoughts and keenest re- searches in pure and applied mathematics. The publication of these monographs was made possible by a notable gift to the Mathematical Association of America by Mrs. Carus as sole trustee of the Edward C. Hegeler Trust Fund. The expositions of mathematical subjects which the monographs will contain are to be set forth in a manner comprehensible not only to teach- ers and students specializing in mathematics, but also to scientific workers in other fields, and especially to the wide circle of thoughtful people who, having a moderate acquaintance with elementary mathematics, wish to extend their knowledge without prolonged and critical study of the mathematical journals and trea- tises. The scope of this series includes also historical and biographical monographs. The Carus Mathematical Monographs NUMBER FIVE A HISTORY OF MATHEMATICS IN AMERICA BEFORE 1900 By DAVID EUGENE SMITH Professor Emeritus of Mathematics Teacliers College, Columbia University and JEKUTHIEL GINSBURG Professor of Mathematics in Yeshiva College New York and Editor of "Scripta Mathematica" Published by THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA with the cooperation of THE OPEN COURT PUBLISHING COMPANY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS THE OPEN COURT COMPANY Copyright 1934 by THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMKRICA Published March, 1934 Composed, Printed and Bound by tClfe QlolUgUt* $Jrr George Banta Publishing Company Menasha, Wisconsin, U. -

Blaschke, Osgood, Wiener, Hadamard and the Early Development Of

Blaschke, Osgood, Wiener, Hadamard and the Early Development of Modern Mathematics in China Chuanming Zong Abstract. In ancient times, China made great contributions to world civi- lization and in particular to mathematics. However, modern sciences includ- ing mathematics came to China rather too late. The first Chinese university was founded in 1895. The first mathematics department in China was for- mally opened at the university only in 1913. At the beginning of the twenti- eth century, some Chinese went to Europe, the United States of America and Japan for higher education in modern mathematics and returned to China as the pioneer generation. They created mathematics departments at the Chinese universities and sowed the seeds of modern mathematics in China. In 1930s, when a dozen of Chinese universities already had mathematics departments, several leading mathematicians from Europe and USA visited China, including Wilhelm Blaschke, George D. Birkhoff, William F. Osgood, Norbert Wiener and Jacques Hadamard. Their visits not only had profound impact on the mathematical development in China, but also became social events sometimes. This paper tells the history of their visits. 2020 Mathematics Subject Classification: 01A25, 01A60. 1. Introduction and Background In 1895, Peiyang University was founded in Tianjin as a result of the westernization movement. In 1898, Peking University was founded in Beijing. They are the earliest universities in China. On May 28, 1900, Britain, USA, France, Germany, Russia, Japan, Italy and Austria invaded China to suppress the Boxer Rebellion1 which was an organized movement against foreign missionaries and their followers. On August 14, 1900, more than 20,000 soldiers of the allied force occupied the Chinese capital Beijing and the emperor’s family with some high ranking officials and servants escaped to Xi’an. -

George David Birkhoff and His Mathematical Work

GEORGE DAVID BIRKHOFF AND HIS MATHEMATICAL WORK MARSTON MORSE The writer first saw Birkhoff in the fall of 1914. The graduate stu dents were meeting the professors of mathematics of Harvard in Sever 20. Maxime Bôcher, with his square beard and squarer shoes, was presiding. In the back of the room, with a different beard but equal dignity, William Fogg Osgood was counseling a student. Dun ham Jackson, Gabriel Green, Julian Coolidge and Charles Bouton were in the business of being helpful. The thirty-year-old Birkhoff was in the front row. He seemed tall even when seated, and a friendly smile disarmed a determined face. I had no reason to speak to him, but the impression he made upon me could not be easily forgotten. His change from Princeton University to Harvard in 1912 was de cisive. Although he later had magnificent opportunities to serve as a research professor in institutions other than Harvard he elected to remain in Cambridge for life. He had been an instructor at Wisconsin from 1907 to 1909 and had profited from his contacts with Van Vleck. As a graduate student in Chicago he had known Veblen and he con tinued this friendsip in the halls of Princeton. Starting college in 1902 at the University of Chicago, he changed to Harvard, remained long enough to get an A.B. degree, and then hurried back to Chicago, where he finished his graduate work in 1907. It was in 1908 that he married Margaret Elizabeth Grafius. It was clear that Birkhoff depended from the beginning to the end on her deep understanding and encouragement. -

Council Congratulates Exxon Education Foundation

from.qxp 4/27/98 3:17 PM Page 1315 From the AMS ics. The Exxon Education Foundation funds programs in mathematics education, elementary and secondary school improvement, undergraduate general education, and un- dergraduate developmental education. —Timothy Goggins, AMS Development Officer AMS Task Force Receives Two Grants The AMS recently received two new grants in support of its Task Force on Excellence in Mathematical Scholarship. The Task Force is carrying out a program of focus groups, site visits, and information gathering aimed at developing (left to right) Edward Ahnert, president of the Exxon ways for mathematical sciences departments in doctoral Education Foundation, AMS President Cathleen institutions to work more effectively. With an initial grant Morawetz, and Robert Witte, senior program officer for of $50,000 from the Exxon Education Foundation, the Task Exxon. Force began its work by organizing a number of focus groups. The AMS has now received a second grant of Council Congratulates Exxon $50,000 from the Exxon Education Foundation, as well as a grant of $165,000 from the National Science Foundation. Education Foundation For further information about the work of the Task Force, see “Building Excellence in Doctoral Mathematics De- At the Summer Mathfest in Burlington in August, the AMS partments”, Notices, November/December 1995, pages Council passed a resolution congratulating the Exxon Ed- 1170–1171. ucation Foundation on its fortieth anniversary. AMS Pres- ident Cathleen Morawetz presented the resolution during —Timothy Goggins, AMS Development Officer the awards banquet to Edward Ahnert, president of the Exxon Education Foundation, and to Robert Witte, senior program officer with Exxon. -

Visionary Calculations Inventing the Mathematical Economy in Nineteenth-Century America

Visionary Calculations Inventing the Mathematical Economy in Nineteenth-Century America By Rachel Knecht B.A., Tufts University, 2011 M.A., Brown University, 2014 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History at Brown University. Providence, Rhode Island May 2018 © Copyright 2018 by Rachel Knecht This dissertation of Rachel Knecht is accepted in its present form by the Department of History as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date __________________ ______________________________________ Seth Rockman, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date __________________ ______________________________________ Joan Richards, Reader Date __________________ ______________________________________ Lukas Rieppel, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date __________________ ______________________________________ Andrew Campbell, Dean of the Graduate School iii Vitae Rachel Knecht received her B.A. in History from Tufts University, magna cum laude, in 2011 and her M.A. in History from Brown University in 2014. Her research has been supported by the Program in Early American Economy and Society at the Library Company of Philadelphia, the American Philosophical Society, the American Antiquarian Society, and the member institutions of the New England Regional Consortium, as well as the Department of History and Graduate School at Brown University. In 2017, she received a Deans’ Faculty Fellowship from Brown and joined the History Department as a Visiting Professor in 2018. iv Acknowledgements This dissertation is the product of many years of help, support, criticism, and inspiration. I am deeply indebted not only to the following people, but also to many others who have encouraged me to see this project to its completion. -

American Mathematical Society

American Mathematical Society FORMER PRESIDENTS J. H. VAN AMRINGE, 1889-1890, E. B. VAN VLECK, 1913-1914, EMORY MCCLINTOCK, 1891-1894, E. W. BROWN, 1915-1916, G. W. HILL, 1895-1896, L. E. DICKSON, 1917-1918, SIMON NEWCOMB, 1897-1898, FRANK MORLEY, 1919-1920, R. S. WOODWARD, 1899-1900, G. A. BLISS, 1921-1922, E. H. MOORE, 1901-1902, OSWALD VEBLEN, 1923-1924, T. S. FISKE, 1903-1904, G. D. BIRKHOFF, 1925-1926, W. F. OSGOOD, 1905-1906, VIRGIL SNYDER, 1927-1928, H. S. WHITE, 1907-1908, E. R. HEDRICK, 1929-1930, MAXIME BÔCHER, 1909-1910, L. P. EISENHART, 1931-1932, H. B. FINE, 1911-1912, A. B. COBLE, 1933-1934, ENDOWMENT FUND In 1923 an Endowment Fund was collected for the support of the ever in creasing number of important mathematical memoirs. Of this fund, which now amounts to some $77,000, a considerable proportion was contributed by members of the Society. PRIZE FUNDS The Bôcher Memorial Prize. This prize was founded in memory of Professor Maxime Bôcher. It is awarded every five years for a notable research memoir in analysis which has appeared during the preceding five years in a recognized journal published in the United States or Canada ; the recipient must be a member of the Society, and not more than fifty years old at the time of publication of his memoir. First (Preliminary) Award, 1923 : To G. D. Birkhoff, for his memoir Dy namical systems with two degrees of freedom. Second Award, 1924: To E. T. Bell, for his memoir Arithmetical paraphrases, and to Solomon Lefschetz, for his memoir On certain numerical invariants with applications to abelian varieties. -

View This Volume's Front and Back Matter

Titles in This Series Volume 8 Kare n Hunger Parshall and David £. Rowe The emergenc e o f th e America n mathematica l researc h community , 1876-1900: J . J. Sylvester, Felix Klein, and E. H. Moore 1994 7 Hen k J. M. Bos Lectures in the history of mathematic s 1993 6 Smilk a Zdravkovska and Peter L. Duren, Editors Golden years of Moscow mathematic s 1993 5 Georg e W. Mackey The scop e an d histor y o f commutativ e an d noncommutativ e harmoni c analysis 1992 4 Charle s W. McArthur Operations analysis in the U.S. Army Eighth Air Force in World War II 1990 3 Pete r L. Duren, editor, et al. A century of mathematics in America, part III 1989 2 Pete r L. Duren, editor, et al. A century of mathematics in America, part II 1989 1 Pete r L. Duren, editor, et al. A century of mathematics in America, part I 1988 This page intentionally left blank https://doi.org/10.1090/hmath/008 History of Mathematics Volume 8 The Emergence o f the American Mathematical Research Community, 1876-1900: J . J. Sylvester, Felix Klein, and E. H. Moor e Karen Hunger Parshall David E. Rowe American Mathematical Societ y London Mathematical Societ y 1991 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 01A55 , 01A72, 01A73; Secondary 01A60 , 01A74, 01A80. Photographs o n th e cove r ar e (clockwis e fro m right ) th e Gottinge n Mathematisch e Ges - selschafft, Feli x Klein, J. J. Sylvester, and E. H. Moore. -

Graduate Studies Texas Tech University

77 75 G-7S 74 GRADUATE STUDIES TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY Men and Institutions in American Mathematics Edited by J. Dalton Tarwater, John T. White, and John D. Miller K C- r j 21 lye No. 13 October 1976 TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY Cecil Mackey, President Glenn E. Barnett, Executive Vice President Regents.-Judson F. Williams (Chairman), J. Fred Bucy, Jr., Bill E. Collins, Clint Form- by, John J. Hinchey, A. J. Kemp, Jr., Robert L. Pfluger, Charles G. Scruggs, and Don R. Workman. Academic Publications Policy Committee.-J. Knox Jones, Jr. (Chairman), Dilford C. Carter (Executive Director and Managing Editor), C. Leonard Ainsworth, Harold E. Dregne, Charles S. Hardwick, Richard W. Hemingway, Ray C. Janeway, S. M. Kennedy, Thomas A. Langford, George F. Meenaghan, Marion C. Michael, Grover E. Murray, Robert L. Packard, James V. Reese, Charles W. Sargent, and Henry A. Wright. Graduate Studies No. 13 136 pp. 8 October 1976 $5.00 Graduate Studies are numbered separately and published on an irregular basis under the auspices of the Dean of the Graduate School and Director of Academic Publications, and in cooperation with the International Center for Arid and Semi-Arid Land Studies. Copies may be obtained on an exchange basis from, or purchased through, the Exchange Librarian, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas 79409. * Texas Tech Press, Lubbock, Texas 16 1976 I A I GRADUATE STUDIES TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY Men and Institutions in American Mathematics Edited by J. Dalton Tarwater, John T. White, and John D. Miller No. 13 October 1976 TEXAS TECH UNIVERSITY Cecil Mackey, President Glenn E. Barnett, Executive Vice President Regents.-Judson F.