Visionary Calculations Inventing the Mathematical Economy in Nineteenth-Century America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathematics Is a Gentleman's Art: Analysis and Synthesis in American College Geometry Teaching, 1790-1840 Amy K

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2000 Mathematics is a gentleman's art: Analysis and synthesis in American college geometry teaching, 1790-1840 Amy K. Ackerberg-Hastings Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Ackerberg-Hastings, Amy K., "Mathematics is a gentleman's art: Analysis and synthesis in American college geometry teaching, 1790-1840 " (2000). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 12669. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/12669 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margwis, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. in the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

S0002-9904-1917-02959-X.Pdf

1917.] EMORY McCLINTOCK. 353 £ = *(*), * = *«). It is clear that corresponding to any point w in the vicinity of f(zo) the function z = ^(£) furnishes n values of z. Also the form of ^(£) would depend on the particular circle chosen, but one form may be transformed into any other by replacing £ by the product of £ and the appropriate nth root of unity. UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO. EMORY McCLINTOCK. BUT few members of the American Mathematical Society at the present time appreciate the magnitude of the services rendered by its former president, Emory McClintock, who died July 10, 1916. He was born September 19, 1840, at Carlisle, Pa. His father was the Rev. John McClintock, a learned Methodist Episcopal clergyman, for a time professor of mathematics, Latin, and Greek in Dickinson College, and during the Civil War chaplain of the American Chapel in Paris. He is perhaps best known as the author, with another, of a " Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature." McClintock went to school for the first time at the age of thirteen, and a year later entered the freshman year of Dickin son College. In 1856, when his father left Dickinson College for New York, he entered Yale, and in 1857 he entered Colum bia as a member of the class of 1859. His remarkable ability excited the admiration of his teachers, Professors Charles Davies and William Guy Peck. In April, 1859 in order to meet an emergency caused by the illness of a member of the teaching staff, he was graduated and appointed tutor in mathe matics. Soon afterwards his father took charge of the Ameri can Chapel in Paris, and in 1860 McClintock resigned his position at Columbia to go abroad. -

A Question of Trust

Delaware Business Times digital edition brought to you by… Spotlight: Two downtown building sales offer hope for market and two large warehouses planned in New Castle May 26, 2020 | Vol. 7 • No. 11 | $2.00 | DelawareBusinessTimes.com 15, 16 A QUESTION Governor: Consumer OF TRUST confi dence key to reopening economy 13 Desperation grows for restaurants, retail as Phase 1 nears 4 Small businesses plead their case to Carney Pandemic reinforces to loosen rules prior to reopening need for downstate broadband 6 Dear Governor Carney State business organizations plea for governor to lighten restrictions 10-13 Spotlight: Two downtown building sales offer hope for market and two large warehouses planned in New Castle To sponsor the Delaware Business Times digital edition, May 26, 2020 | Vol. 7 • No. 11 | $2.00 | DelawareBusinessTimes.com 15, 16 contact: [email protected] A QUESTION Governor: Consumer OF TRUST confi dence key to reopening economy 13 Desperation grows for restaurants, retail as Phase 1 nears 4 Small businesses plead their case to Carney Pandemic reinforces to loosen rules prior to reopening need for downstate broadband 6 Dear Governor Carney State business organizations plea for governor to lighten restrictions 10-13 Spotlight: Two downtown building sales offer hope for market and two large warehouses planned in New Castle May 26, 2020 | Vol. 7 • No. 11 | $2.00 | DelawareBusinessTimes.com A QUESTION Governor: Consumer confi dence key to OF TRUST reopening economy 13 esperation grows for restaurants retail as Phase 1 -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1941, Volume 36, Issue No. 1

ma SC 5Z2I~]~J41 MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME XXXVI BALTIMORE 1941 CONTENTS OF VOLUME XXXVI PAGE THE SUSQUEHANNOCK FORT ON PISCATAWAY CREEK. By Alice L. L. Ferguson, 1 ELIZA GODBFROY: DESTINY'S FOOTBALL. By William D. Hoyt, Jr., ... 10 BLUE AND GRAY: I. A BALTIMORE VOLUNTEER OF 1864. By William H. fames, 22 II. THE CONFEDERATE RAID ON CUMBERLAND, 1865. By Basil William Spalding, 33 THE " NARRATIVE " OF COLONEL JAMES RIGBIE. By Henry Chandlee Vorman, . 39 A WEDDING OF 1841, 50 THE LIFE OF RICHARD MALCOLM JOHNSTON IN MARYLAND, 1867-1898. By Prawds Taylor Long, concluded, 54 LETTERS OF CHARLES CARROLL, BARRISTER, continued, 70, 336 BOOK REVIEWS, 74, 223, 345, 440 NOTES AND QUERIES, 88, 231, 354, 451 PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY, 90, 237, 455 LIST OF MEMBERS, 101 THE REVOLUTIONARY IMPULSE IN MARYLAND. By Charles A. Barker, . 125 WILLIAM GODDARD'S VICTORY FOR THE FREEDOM OF THE PRESS. By W. Bird Terwilliger, 139 CONTROL OF THE BALTIMORE PRESS DURING THE CIVIL WAR. By Sidney T. Matthews, 150 SHIP-BUILDING ON THE CHESAPEAKE: RECOLLECTIONS OF ROBERT DAWSON LAMBDIN, 171 READING INTERESTS OF THE PROFESSIONAL CLASSES IN COLONIAL MARYLAND, 1700-1776. By Joseph Towne Wheeler, 184, 281 THE HAYNIE LETTERS 202 BALTIMORE COUNTY LAND RECORDS OF 1687. By Louis Dow Scisco, . 215 A LETTER FROM THE SPRINGS, 220 POLITICS IN MARYLAND DURING THE CIVIL WAR. By Charles Branch Clark, . 239 THE ORIGIN OF THE RING TOURNAMENT IN THE UNITED STATES. By G. Harrison Orians, 263 RECOLLECTIONS OF BROOKLANDWOOD TOURNAMENTS. By D. Sterett Gittings, 278 THE WARDEN PAPERS. -

Autonomy As State Prevention: the Palestinian Question After Camp David, 1979–1982

Autonomy as State Prevention: The Palestinian Question after Camp David, 1979–1982 Seth Anziska Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development, Volume 8, Number 2, Summer 2017, pp. 287-310 (Article) Published by University of Pennsylvania Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/hum.2017.0020 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/665530 Access provided by University College London (UCL) (26 Sep 2017 09:59 GMT) Seth Anziska Autonomy as State Prevention: The Palestinian Question after Camp David, 1979–1982 Introduction Scholars have long explored the legal and institutional continuities that inhere in the transition from the era of late empire to the rise of nation-states, underscoring how external rule produced particular trajectories of Arab state formation.1 Extensive violence in Iraq and Syria today has directed much of that attention to the influence of British and French mandatory rule on the emergence of nation-states in the region.2 One striking feature of this transition was the rhetoric of self-determination and purportedly time-limited, developmental intervention that the mandatory powers used to extend control over local populations after the fall of the Ottoman Empire in 1918. In asserting a role as protector of nations emerging from the postwar partitions, the League of Nations helped neutralize local struggles for independence.3 The conceptual framework of “transformative occupation” in the modern Middle East illuminates the techniques of foreign rule within these wider imperial histories while linking them to ambitious programs of development.4 Whether in the name of civilization or modernity, whether by a colonial or mandated power, imposing the practices of Western governance on “backward” peoples and space characterized trans- formative occupation regimes.5 In this essay, I examine how a particular practice within the political and diplomatic repertoire of transformative occupation—the promotion of local autonomy—was successfully deployed in the Israeli-Palestinian arena. -

Consummate Coach Tim Murphy’S Formidable Game S:7”

Daniel Aaron • Max Beckmann’s Modernity • Sexual Assault November-December 2015 • $4.95 Consummate Coach Tim Murphy’s formidable game S:7” Invest In What Lasts How do you pass down what you’ve spent your life building up? A Morgan Stanley Financial Advisor can help you create a legacy plan based on the values you live by. So future generations can benefit from not just your money, but also your example. Let’s have that conversation. morganstanley.com/legacy S:9.25” © 2015 Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC. Member SIPC. CRC 1134840 04/15 151112_MorganStanley_Ivy.indd 1 9/21/15 1:59 PM NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2015 VOLUME 118, NUMBER 2 FEATURES 35 Murphy Time | by Dick Friedman The recruiter, tactician, and educator who has become one of the best coaches in football 44 Making Modernity | by Joseph Koerner On the meanings and history of Max Beckmann’s iconic self-portrait p. 33 48 Vita: Joseph T. Walker | by Thomas W. Walker Brief life of a scientific sleuth: 1908-1952 50 Chronicler of Two Americas | by Christoph Irmscher An appreciation of Daniel Aaron, with excerpts from his new Commonplace Book JOHN HARVard’s JournAL 41.37. 41.37. R 17 Smith Campus Center under wraps, disturbing sexual-assault ULL IMAGE F findings, a law professor plumbs social problems, the campaign OR F NIVERSITY crosses $6 billion, cutting class for Christmas, lesser gains U and new directions for the endowment, fall themes and a SSOCIATION FUND, B A ARVARD H brain-drain of economists, Allston science complex, the Under- USEUM, RARY, RARY, B M graduate on newfangled reading, early-season football, and I L a three-point shooter recovers her stroke after surgery DETAIL, PLEASE 44 SEE PAGE EISINGER R OUGHTON H p. -

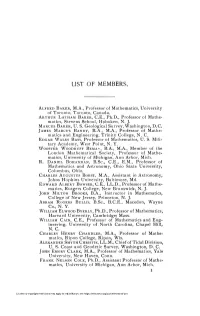

List of Members

LIST OF MEMBERS, ALFRED BAKER, M.A., Professor of Mathematics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada. ARTHUR LATHAM BAKER, C.E., Ph.D., Professor of Mathe matics, Stevens School, Hpboken., N. J. MARCUS BAKER, U. S. Geological Survey, Washington, D.C. JAMES MARCUS BANDY, B.A., M.A., Professor of Mathe matics and Engineering, Trinit)^ College, N. C. EDGAR WALES BASS, Professor of Mathematics, U. S. Mili tary Academy, West Point, N. Y. WOOSTER WOODRUFF BEMAN, B.A., M.A., Member of the London Mathematical Society, Professor of Mathe matics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. R. DANIEL BOHANNAN, B.Sc, CE., E.M., Professor of Mathematics and Astronomy, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. CHARLES AUGUSTUS BORST, M.A., Assistant in Astronomy, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Md. EDWARD ALBERT BOWSER, CE., LL.D., Professor of Mathe matics, Rutgers College, New Brunswick, N. J. JOHN MILTON BROOKS, B.A., Instructor in Mathematics, College of New Jersey, Princeton, N. J. ABRAM ROGERS BULLIS, B.SC, B.C.E., Macedon, Wayne Co., N. Y. WILLIAM ELWOOD BYERLY, Ph.D., Professor of Mathematics, Harvard University, Cambridge*, Mass. WILLIAM CAIN, C.E., Professor of Mathematics and Eng ineering, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N. C. CHARLES HENRY CHANDLER, M.A., Professor of Mathe matics, Ripon College, Ripon, Wis. ALEXANDER SMYTH CHRISTIE, LL.M., Chief of Tidal Division, U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, Washington, D. C. JOHN EMORY CLARK, M.A., Professor of Mathematics, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. FRANK NELSON COLE, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Mathe matics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. -

Coronavirus Sends Students Home

The Harvard Crimson THE UNIVERSITY DAILY, EST. 1873 | VOLUME CXLVII NO. 34 | CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS | WEDNESDAY, MARCH 11, 2020 NEWS PAGE 5 EDITORIAL PAGE 6 SPORTS PAGE 8 Archaeologist discusses the Pacific Harvard’s choice to close its doors Women’s basketball halts losing in the prehistoric era gives us deep reason for worry streak Friday, then loses to Yale CORONAVIRUS SENDS STUDENTS HOME INSIDE THIS Students Must ISSUE Vacate, Classes Move Online Unions Reply to Closures By THE CRIMSON NEWS STAFF Three unions say they All Harvard courses will move are making contingen- to remote instruction begin- cy plans and cancelling ning March 23 as a result of a events after Harvard’s growing global coronavirus announcement that it outbreak, University President will send undergrads Lawrence S. Bacow announced home and move to on- in an email Tuesday morning. line classes. The University will also ask students not to return from spring break. SEE UNIONS PAGE 4 “Students are asked not to return to campus after Spring Recess and to meet academ- ic requirements remotely until Seniors Party further notice,” Bacow wrote in the email. Before Packing “Students who need to re- main on campus will also re- ceive instruction remotely and must prepare for severely lim- ited on-campus activities and interactions. All graduate stu- dents will transition to remote work wherever possible,” Ba- cow added. The move follows both similar decisions at other Ivy League universities in recent Harvard seniors spent days and rapid changes on On Tuesday morning, Harvard University announced the upcoming transition to virtual instruction for graduate and undergraduate classes. -

240 Years of the Wealth of Nations 240 Anos De a Riqueza Das Nações

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0103-6351/3743 240 years of The Wealth of Nations 240 anos de A Riqueza das Nações Maria Pia Paganelli Trinity University Abstract Resumo Why should we read a book printed 240 Por que deveríamos ler um livro publicado há years ago? The book is old. Our circum- 240 anos? Trata-se de um livro antigo. Nossas stances and institutions are different. Its ex- circunstâncias e instituições são diferentes. Seus amples are dated. Its policies are irrelevant exemplos são datados. Suas recomendações de today. Its economic theories are full of mis- política são irrelevantes hoje. Suas teorias econô- takes. Even its political ideology is ambigu- micas estão repletas de erros. Mesmo a sua ideo- ous. So, why bother reading this old book? logia política é ambígua. Então, por que se dar ao trabalho de ler este velho livro? Keywords Palavras-chave Adam Smith; Wealth of Nations; wealth; Adam Smith; A Riqueza das Nações; riqueza; growth; justice. crescimento; justiça. JEL Codes B12; O10. Códigos JEL B12; O10. v.27 n.2 p.7-19 2017 Nova Economia� 7 Paganelli “Convictions are more dangerous enemies of truth than lies” Friedrich Nietzsche Why would anybody care to read a book that is almost two and a half centuries old? Better (or worse), why would anybody refer to – and yet not read – a book that is well over two centuries old? Or maybe I should ask: why should anybody read a book that is well over two centuries old? Age aside, the Wealth of Nations is also in many ways a dated book. -

A History of Mathematics in America Before 1900.Pdf

THE BOOK WAS DRENCHED 00 S< OU_1 60514 > CD CO THE CARUS MATHEMATICAL MONOGRAPHS Published by THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Publication Committee GILBERT AMES BLISS DAVID RAYMOND CURTISS AUBREY JOHN KEMPNER HERBERT ELLSWORTH SLAUGHT CARUS MATHEMATICAL MONOGRAPHS are an expression of THEthe desire of Mrs. Mary Hegeler Carus, and of her son, Dr. Edward H. Carus, to contribute to the dissemination of mathe- matical knowledge by making accessible at nominal cost a series of expository presenta- tions of the best thoughts and keenest re- searches in pure and applied mathematics. The publication of these monographs was made possible by a notable gift to the Mathematical Association of America by Mrs. Carus as sole trustee of the Edward C. Hegeler Trust Fund. The expositions of mathematical subjects which the monographs will contain are to be set forth in a manner comprehensible not only to teach- ers and students specializing in mathematics, but also to scientific workers in other fields, and especially to the wide circle of thoughtful people who, having a moderate acquaintance with elementary mathematics, wish to extend their knowledge without prolonged and critical study of the mathematical journals and trea- tises. The scope of this series includes also historical and biographical monographs. The Carus Mathematical Monographs NUMBER FIVE A HISTORY OF MATHEMATICS IN AMERICA BEFORE 1900 By DAVID EUGENE SMITH Professor Emeritus of Mathematics Teacliers College, Columbia University and JEKUTHIEL GINSBURG Professor of Mathematics in Yeshiva College New York and Editor of "Scripta Mathematica" Published by THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA with the cooperation of THE OPEN COURT PUBLISHING COMPANY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS THE OPEN COURT COMPANY Copyright 1934 by THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMKRICA Published March, 1934 Composed, Printed and Bound by tClfe QlolUgUt* $Jrr George Banta Publishing Company Menasha, Wisconsin, U. -

Economics for the Masses: the Visual Display of Economic Knowledge in the United States (1921-1945) Yann Giraud, Loïc Charles

Economics for the Masses: The Visual Display of Economic Knowledge in the United States (1921-1945) Yann Giraud, Loïc Charles To cite this version: Yann Giraud, Loïc Charles. Economics for the Masses: The Visual Display of Economic Knowledge in the United States (1921-1945). 2013. hal-00870490 HAL Id: hal-00870490 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00870490 Preprint submitted on 7 Oct 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Thema Working Paper n°2010-03 Université de Cergy Pontoise, France Economics for the Masses : The Visual Display of Economic Knowledge in the United States (1921-1945) Giraud Yann Charles Loic June, 2010 Economics for the Masses: The Visual Display of Economic Knowledge in the United States (1921-1945) Loïc Charles (EconomiX, Université de Reims and INED) & Yann Giraud (Université de Cergy-Pontoise, THEMA)1 June 2010 Abstract: The rise of visual representation in economics textbooks after WWII is one of the main features of contemporary economics. In this paper, we argue that this development has been preceded by a no less significant rise of visual representation in the larger literature devoted to social and scientific issues, including economic textbooks for non-economists as well as newspapers and magazines. -

In 193X, Constance Rourke's Book American Humor Was Reviewed In

OUR LIVELY ARTS: AMERICAN CULTURE AS THEATRICAL CULTURE, 1922-1931 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Schlueter, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Thomas Postlewait, Adviser Professor Lesley Ferris Adviser Associate Professor Alan Woods Graduate Program in Theatre Copyright by Jennifer Schlueter c. 2007 ABSTRACT In the first decades of the twentieth century, critics like H.L. Mencken and Van Wyck Brooks vociferously expounded a deep and profound disenchantment with American art and culture. At a time when American popular entertainments were expanding exponentially, and at a time when European high modernism was in full flower, American culture appeared to these critics to be at best a quagmire of philistinism and at worst an oxymoron. Today there is still general agreement that American arts “came of age” or “arrived” in the 1920s, thanks in part to this flogging criticism, but also because of the powerful influence of European modernism. Yet, this assessment was not, at the time, unanimous, and its conclusions should not, I argue, be taken as foregone. In this dissertation, I present crucial case studies of Constance Rourke (1885-1941) and Gilbert Seldes (1893-1970), two astute but understudied cultural critics who saw the same popular culture denigrated by Brooks or Mencken as vibrant evidence of exactly the modern American culture they were seeking. In their writings of the 1920s and 1930s, Rourke and Seldes argued that our “lively arts” (Seldes’ formulation) of performance—vaudeville, minstrelsy, burlesque, jazz, radio, and film—contained both the roots of our own unique culture as well as the seeds of a burgeoning modernism.