Interview with David J. Fischer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Seychelles Law Reports

THE SEYCHELLES LAW REPORTS DECISIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT, CONSTITUTIONAL COURT AND COURT OF APPEAL ________________ 2017 _________________ PART 1 (Pp i-xii, 1-268) Published by Authority of the Chief Justice (2017) SLR EDITORIAL BOARD Chief Justice – ex officio Attorney-General – ex officio Mr Kieran Shah of Middle Temple, Barrister Mr Bernard Georges of Gray’s Inn, Barrister CITATION These reports are cited thus: (2017) SLR Printed by ii THE SEYCHELLES JUDICIARY THE COURT OF APPEAL Hon F MacGregor, President Hon S Domah Hon A Fernando Hon J Msoffe Hon M Twomey THE SUPREME COURT (AND CONSTITUTIONAL COURT) Hon M Twomey,Chief Justice Hon D Karunakaran Hon B Renaud Hon M Burhan Hon G Dodin Hon F Robinson Hon E De Silva Hon C McKee Hon D Akiiki-Kiiza Hon R Govinden Hon S Govinden Hon S Nunkoo Hon M Vidot Hon L Pillay Master E Carolus iii (2017) SLR iv CONTENTS Digest of Cases ................................................................................................ vii Cases Reported Amesbury v President of Seychelles & Constitutional Appointments Authority ........ 69 Benstrong v Lobban ............................................................................................... 317 Bonnelame v National Assembly of Seychelles ..................................................... 491 D’Acambra & Esparon v Esparon ........................................................................... 343 David & Ors v Public Utilities Corporation .............................................................. 439 Delorie v Government of Seychelles -

1982 Annual Meetings of the Boards of Governors

INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT INTERNATIONAL FINANCE CORPORATION INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION Public Disclosure Authorized 1982 ANNUAL MEETINGS OF THE BOARDS OF GOVERNORS SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Toronto, Ontario, CANADA SEPTEMBER 6-9, 1982 Public Disclosure Authorized INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT INTERNATIONAL FINANCE CORPORATION INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION 1982 ANNUAL MEETINGS OF THE BOARDS OF GOVERNORS SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS Toronto, Ontario, CANADA SEPTEMBER 6-9, 1982 INTRODUCTORY NOTE The 1982 Annual Meeting of the Board of Governors of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, held jointly with that of the In ternational Monetary Fund, took place in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, September 6-9 (inclusive). The Honorable Abdlatif Y. AI-Hamad, Gover nor of the Bank and Fund for Kuwait, served as Chairman. The Annual Meetings of the Bank's affiliates, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the International Development Association (IDA), were held in conjunction with the Annual Meeting of the Bank. The Summary Proceedings record, in alphabetical order of member countries, the texts of statements by Governors relating to the activities of the Bank, IFC and IDA. The texts of statements concerning the IMF are published separately by the Fund. T.T.THAHANE Vice President and Secretary THE WORLD BANK Washington, D.C. January, 1983 iii CONTENTS Page Opening Remarks by Pierre Elliott Trudeau Prime Minister of Canada .............................. Opening Address by the Chairman Abdlatif Y. AI-Hamad Governor of the Bank and Fund for Kuwait . 6 Annual Address by A. W. Clausen President of the World Bank. .. .. ... ... 12 Report by Manuel Ulloa Elias Chairman of the Development Committee . -

Our Common Future

Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future Table of Contents Acronyms and Note on Terminology Chairman's Foreword From One Earth to One World Part I. Common Concerns 1. A Threatened Future I. Symptoms and Causes II. New Approaches to Environment and Development 2. Towards Sustainable Development I. The Concept of Sustainable Development II. Equity and the Common Interest III. Strategic Imperatives IV. Conclusion 3. The Role of the International Economy I. The International Economy, the Environment, and Development II. Decline in the 1980s III. Enabling Sustainable Development IV. A Sustainable World Economy Part II. Common Challenges 4. Population and Human Resources I. The Links with Environment and Development II. The Population Perspective III. A Policy Framework 5. Food Security: Sustaining the Potential I. Achievements II. Signs of Crisis III. The Challenge IV. Strategies for Sustainable Food Security V. Food for the Future 6. Species and Ecosystems: Resources for Development I. The Problem: Character and Extent II. Extinction Patterns and Trends III. Some Causes of Extinction IV. Economic Values at Stake V. New Approach: Anticipate and Prevent VI. International Action for National Species VII. Scope for National Action VIII. The Need for Action 7. Energy: Choices for Environment and Development I. Energy, Economy, and Environment II. Fossil Fuels: The Continuing Dilemma III. Nuclear Energy: Unsolved Problems IV. Wood Fuels: The Vanishing Resource V. Renewable Energy: The Untapped Potential VI. Energy Efficiency: Maintaining the Momentum VII. Energy Conservation Measures VIII. Conclusion 8. Industry: Producing More With Less I. Industrial Growth and its Impact II. Sustainable Industrial Development in a Global Context III. -

Fischer, David

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR DAVID J. FISCHER Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy and Robert S. Pastorino Initial interview date: March 6, 199 Copyright 2000 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Connecticut raised in Minnesota Brown University University of Vienna Harvard Law School Army Security Agency Entered Foreign Service - 1961 Frankfurt, -ermany - Consular Officer 1961-196. Duties National -erman Party CODELs Cu0an Missile Crisis 1nspection Foreign Service 1nstitute - Polish Language Training 196.-1962 3arsaw, Poland - Rotation Officer 1962-1968 -overnment Environment US1A programs E6patriates Security Soviets Communists Catholic Church Student uprising -erman representation State Department - Eastern Europe 1968 Secretary of State 3illiam Rogers 1ntelligence sources State Department - ACDA 1968-1969 1 China relations State Department- SALT Negotiations 1969-1972 Secretary to delegation Soviet views U.S. views M1RVs -erry Smith New :ork Times ;leak“ ABMs Kissinger>s China visit Sofia, Bulgaria - Political/Economic Officer 1972-1972 U.S. relations Security Environment 1ntelligence Turkish minority Communists Kathmandu, Nepal - Political/Economic Officer 1972-1977 Environment Monarchy Travel Nepal>s neigh0ors -overnment operations Hashish/marijuana Carol Laise Mount Everest Am0assador Marquita Maytag State Department - Arms Control Officer 1977-1978 State Department - Pu0lic Affairs 1978-1979 Panama Canal Treaty SALT 11 Congressional relations NSC ACS -

The Indian Ocean Region in the 21St Century: Geopolitical, Economic, and Environmental Ties

The Indian Ocean Region in the 21st Century: geopolitical, economic, and environmental ties Dr Alexander E Davis La Trobe University, Department of Politics, Media and Philosophy and Australia India Institute, University of Melbourne Dr Jonathan N Balls School of Geography and Australia India Institute, University of Melbourne Sid & Fiona Myer THE INDIAN OCEAN REGION IN THE 21ST CENTURY: GEOPOLITICAL, ECONOMIC, AND ENVIRONMENTAL TIES FAMILY FOUNDATION 1 The Indian Ocean Region in the 21st Century: geopolitical, economic, and environmental ties Dr Alexander E Davis La Trobe University, Department of Politics, Media and Philosophy and Australia India Institute, University of Melbourne Dr Jonathan N Balls School of Geography and Australia India Institute, University of Melbourne 1.0 Introduction The Indian Ocean littoral, which spans Australasia, South East Asia, South Asia, West Asia, and Eastern and Southern Africa, is home to 2.7 billion people. It is one of the world’s youngest regions - the average age of India Ocean littoral is under 30. The region is rich in natural resources, has critical fish stocks, and is home to some of the world’s fastest growing economies. 40 per cent of the world’s offshore oil production comes from the Indian Ocean. 80 per cent of the world’s oil shipments travel through its waters, with the region at the heart of connections that extend on to the Middle East, Africa, East Asia, Europe, and the Americas. Aside from economic connections, environmental threats, including rising levels of pollution and climate change, increasingly tie the future prosperity of Indian Ocean states together. The Indian Ocean region has not featured prominently in the imagination of Australia’s politicians, policy- makers, or publics in recent history. -

Conservation of Marine Resources in Seychelles

Conservation of Marine Resources in Seychelles Report on Current Status and Future Management by RODNEY V. SALM IUCN Consultant Report of International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural to the government of Seychelles prepared with the financial support of the United Nations Environment Programme and the World Wildlife Fund Morges, Switzerland August 1978 CONSERVATION OF MARINE RESOURCES IN SEYCHELLES Report on Current Status and Future Management by RODNEY V. SALM IUCN Consultant Report of International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources to the Government of Seychelles prepared with the financial support of the United Nations Environment Programme and the World Wildlife Fund Morges, Switzerland August 1978 FOREWORD The importance of marine resources and the delicacy of the support system upon which they depend is becoming increasingly appreciated at both national and inter- national levels. The current IUCN and World Wildlife Fund Marine Conservation Programme specifically ad- dresses to this fact. Seychelles relies heavily on marine resources, not only as food for the inhabitants and for export, but also on the economic potential of the aesthetic characteristics of the physical and biological components of the surround- ing marine ecosystem. In this regard, the government of Seychelles has not only responded to international concern over the protection of marine resources but has taken some measures to protect and to regulate the exploitation of these resources. The government recognises that these measures are in- adequate for the long-term sustenance of these resources and has accordingly sought advice to elaborate a more realistic approach. The present report, and the recom- mendations therein, attempts to outline basic conservation needs for the maintenance of the productivity of the marine resources and suggests steps that need to be taken to meet them. -

Supplement to the London Gazette, Ist January 1969

20 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, IST JANUARY 1969 Clarence Eric Stanley BAILEY, M.B.E., M.B., James Marshall MESSENGER, lately Principal Ch.B., Chief Medical Officer, Antigua. of the Nairobi Polytechnic, Kenya. Basil Leo BALCOMBE, J.P. For services to the John Edward MORRIS, Deputy Head, community in Saint Vincent. Chemistry Division, Rubber Research Miss Kathleen Margaret BARR, Principal Institute, Malaya. Matron, Sabah. Robert Urquhart PAUL. For services to civil Denys Henry BIRCH, British subject resident aviation in the New Hebrides. in the United Arab Republic. Ronald Thomas George PLATT, British subject Clement James Richard BRIDGE, Senior Agri- resident in the United States of America. cultural Officer, Sabah. Harold PRESTON, Bursar, University of CHIU Lut-sau, M.B.E. For services to the Ibadan, Nigeria. community in Hong Kong. Gerald Barker READ, British subject resident George Maurice COLE. For voluntary public in the Sudan. service in the Bahama Islands. Anthony Gilmore REYNOLDS, United King- Peter COLLENETTE, lately Director, Geologi- dom citizen resident in India. cal Survey, East Malaysia. John Heads RHODES, Chief Agricultural Alan CROTTY, British subject resident in the Officer, Lesotho. United States of America. Reginald Frederick Arman ROGERS, Quantity Ratu Jione Atonio Rabici DOVI, M.B.E., M.B., Surveyor, National Universities' Commission, Ch.B., lately Divisional Medical Officer, Nigeria. Eastern Division, Fiji. Eric Freeth ROPER, Chief Engineer, Electricity Arthur Daniel DUFFY, Commissioner of Inland Department, Public Utilities Board, Singapore. Revenue, Hong Kong. Thomas Emmanuel RYAN, M.B.E., Permanent Jean Desire Maxime FERRARI, M.B., B.Ch. Secretary, Ministry of Social Services, For services to health and social welfare in Montserrat. -

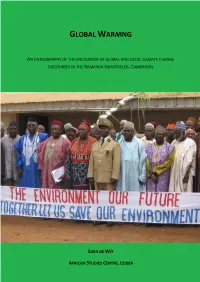

Global Warning

GLOBAL WARNING AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF THE ENCOUNTER OF GLOBAL AND LOCAL CLIMATE CHANGE DISCOURSES IN THE BAMENDA GRASSFIELDS, CAMEROON SARA DE WIT AFRICAN STUDIES CENTRE, LEIDEN Research Master Thesis in African Studies African Studies Centre (ASC), Leiden University February 2011 “Global Warning” Sara de Wit ([email protected]) Supervisors Prof. dr. Mirjam de Bruijn Prof. dr. Wouter van Beek i For my father, brother and sister Sharing in your love is a wonderful experience ii Table of contents CHAPTER ONE: Introduction 1.1 What this thesis is about, problem statement, chapter outline………………………………………………………….…1 CHAPTER TWO: Theoretical and methodological considerations 2.1 The scope of study: from Kyoto to the Bamenda Grassfields and back to Copenhagen………………………17 2.2 Travelling discourses: Studying global and local connectivity……………………………………………………………..20 2.3 Social constructivism as an alternative ‘lens’……………………………………………………………………………………..27 2.3.1 Media(ted) discourses of science and politics…………………………………………………………………….30 2.3.2 Science and its struggle for ‘truth’………………………………………………………………………………………33 2.4 The power of discourses, or discourses as power………………………………………………………………………………37 2.4.1 Foucault’s notion of power/knowledge……………………………………………………………………………...40 CHAPTER THREE: Talking climate change into existence – The role of NGOs in disseminating the green message 3.1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….42 3.2 The modern environmental era: The social construction of climate change in historical perspective…48 3.2.1 Poetic -

IDL-29220.Pdf

MANAGING THE MONSTER This page intentionally left blank MANAGING THE MONSTER Urban Waste and Governance in Africa Edited by Adepoju G. Onibokun INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH CENTRE Ottawa • Cairo • Dakar • Johannesburg • Montevideo • Nairobi • New Dehi • Singapore Published by the International Development Research Centre PO Box 8500, Ottawa, ON, Canada K1G 3H9 © International Development Research Centre 1999 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under title : Managing the monster : urban waste and governance in Africa Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-88936-880-5 1. Refuse and refuse disposal — Africa. 2. Urbanization — Environmental aspects — Africa. 3. Environmental policy — Africa. I. Onibokun, Adepoju G., 1943- . II. International Development Research Centre (Canada). TD790.M36 1999 363.72'8'6'096 C99-980242-9 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechan- ical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the International Development Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of the International Development Research Centre. Mention of a proprietary name does not constitute endorsement of the product and is given only for information. A microfiche edition is available. IDRC Books endeavours to produce environmentally friendly publications. All paper used is recycled as well as recyclable. All inks and coatings are vegetable- based products. CONTENTS Foreword vii — LucJ.A. Mougeot Preface ix Chapter 1 Governance and Waste Management in Africa 1 — A.G. Onibokun and A.J. Kumuyi Chapter 2 Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire 11 — Koffi Attahi Chapter 3 Ibadan, Nigeria 49 — A.G. -

Panique Aux Seychelles À L'approche De L

Panique aux Seychelles à l’approche de l’ouragan « Démocratie » (1) Jean-François Dupaquier Afrikarabia, 9 avril 2016 L’archipel de l’océan indien n’est pas seule- de s’étendre sur les raisons de son limogeage. Le nu- ment la destination huppée des touristes oc- méro 2 de la police est bien placé pour savoir que sa cidentaux et des voyages de noces. Afrikara- liberté d’expression est récente, et qu’il ne doit pas bia vous propose de regarder derrière son dé- trop en dire. Il y a quelques années, le moindre écart cor de plages et de cocotiers de mer, avec un de langage lui aurait coûté beaucoup plus cher. grand reportage de notre envoyé spécial Jean- François Dupaquier. Premier article consacré « James Michel voit venir la fin de son à la violence politique aux Seychelles depuis l’indépendance. système » L’hebdomadaire Le Seychellois Hebdo titre en pre- Après la longue dictature du président France- mière page de son édition du 18 mars 2016 : « Is Albert René et de son parti unique le SPPF (« Sey- the victimisation axe starting to fall ? » (est-ce que chelles People Progressive Front »), les Seychellois la hache de la victimisation commence à tomber ? »). reçoivent avec une prudence teintée de crainte toute « Victimisation » est un terme anglais dont le créole information politique inattendue. Jean-François Fer- seychellois fait un usage particulier. Il dit l’entrée de rari, 56 ans, un homme de belle prestance, nous reçoit la personne dans l’ère de la sanction, de la punition, dans son bureau qui jouxte le jardin botanique de de l’exclusion. -

IN the NEWS South Africa

FOLLOW THE MAN WHO FOLLOWED HIS CONSCIENCE AMERICA Tills authorized eolleetorV video fea- uires aii r\rlnsKe itttmipw with N4?wm Mandela and ne1v<ir-erfieti-lk*lm'e footage, including comment* by: President Ce«r^<" Bti-.li Spike Lee Jaue. Fonda Robert DeNiru N.Y. Mayj|r David l>inkin< and more. Plus musical tribute* l>yi Stevif Jolinn| Aretha F Ladysmith Black and many A portion of the proeeeda from i'ach sale will In* donated to The I\el<?on Mandi'la Freedom Fund and the we^Jkly television program South Afriea Now Running time: *>(> minutes. Produced In \m- <iM§Si Attanltt, Recotdirtg Goip, ft Time Wmm Comfjaoj MAY-JUNE 1991 AMERICAS VOLUME 36. NUMBER 3 LEADING MAGAZINE ON AFRICA A Publication oithe ^REPORT African-American Institute The Update 5 African-American Institute Editor: Tunji Ijxrdner.jr. Chairman South Africa Maurice Tempelsman The ABCs of Apartheid 13 By Peter Tygesen President Vivian Lowery Derryck John Samuel: Ending Apartheid Education 18 By Margaret A. Novicki Publisher Namibia Frank E. Ferrari Bridging the Gap 23 Editor-in-Chief By Colleen lu>we Morna Margaret A. Novicki New Ghanaian Order Page 34 South Africa Production Editor The Pariah's New Pals 28 Joseph Margolis By Colleen Lowe Morna Assistant Editor Land and the Landless 31 Tunji Lardner. Jr. By Patrick Laurence Assistant Editor Ghana Russell Geekie Flt.-Lt. Jerry Rawlings: Constructing a New Constitutional Order 34 Contributing Editors By Margaret A. Novicki Michael Maren Andrew Meldrum Benin Daphne Topouzis A Victory for Democracy 39 Art Director By George Neavoll Kenneth Jay Ross A Vote for Democracy Msgr. -

Over Two Thousand Mayors from Fifty-Four Countries Call for the Immediate Release of Nelson Mandela and Other South African Political Prisoners

Over Two Thousand Mayors from Fifty-Four Countries Call for the Immediate Release of Nelson Mandela and Other South African Political Prisoners http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuun1982_18 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Over Two Thousand Mayors from Fifty-Four Countries Call for the Immediate Release of Nelson Mandela and Other South African Political Prisoners Alternative title Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against ApartheidNo. 16/82 Author/Creator United Nations Centre against Apartheid Publisher United Nations, New York Date 1982-08-00 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1982 Source Northwestern University Libraries Description A Declaration calling for the immediate and unconditional release of Nelson Mandela and other South African political prisoners detained for their political views under the apartheid laws, has now been signed by 2,225 Mayors from 54 countries.