Written Evidence Submitted by Talktalk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gigabit-Broadband in the UK: Government Targets and Policy

BRIEFING PAPER Number CBP 8392, 30 April 2021 Gigabit-broadband in the By Georgina Hutton UK: Government targets and policy Contents: 1. Gigabit-capable broadband: what and why? 2. Gigabit-capable broadband in the UK 3. Government targets 4. Government policy: promoting a competitive market 5. Policy reforms to help build gigabit infrastructure Glossary www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Gigabit-broadband in the UK: Government targets and policy Contents Summary 3 1. Gigabit-capable broadband: what and why? 5 1.1 Background: superfast broadband 5 1.2 Do we need a digital infrastructure upgrade? 5 1.3 What is gigabit-capable broadband? 7 1.4 Is telecommunications a reserved power? 8 2. Gigabit-capable broadband in the UK 9 International comparisons 11 3. Government targets 12 3.1 May Government target (2018) 12 3.2 Johnson Government 12 4. Government policy: promoting a competitive market 16 4.1 Government policy approach 16 4.2 How much will a nationwide gigabit-capable network cost? 17 4.3 What can a competitive market deliver? 17 4.4 Where are commercial providers building networks? 18 5. Policy reforms to help build gigabit infrastructure 20 5.1 “Barrier Busting Task Force” 20 5.2 Fibre broadband to new builds 22 5.3 Tax relief 24 5.4 Ofcom’s work in promoting gigabit-broadband 25 5.5 Consumer take-up 27 5.6 Retiring the copper network 28 Glossary 31 ` Contributing Authors: Carl Baker, Section 2, Broadband coverage statistics Cover page image copyright: Blue Fiber by Michael Wyszomierski. -

Register of Journalists' Interests

REGISTER OF JOURNALISTS’ INTERESTS (As at 11 July 2018) INTRODUCTION Purpose and Form of the Register Pursuant to a Resolution made by the House of Commons on 17 December 1985, holders of photo- identity passes as lobby journalists accredited to the Parliamentary Press Gallery or for parliamentary broadcasting are required to register: ‘Any occupation or employment for which you receive over £770 from the same source in the course of a calendar year, if that occupation or employment is in any way advantaged by the privileged access to Parliament afforded by your pass.’ Administration and Inspection of the Register The Register is compiled and maintained by the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Anyone whose details are entered on the Register is required to notify that office of any change in their registrable interests within 28 days of such a change arising. An updated edition of the Register is published approximately every 6 weeks when the House is sitting. Changes to the rules governing the Register are determined by the Committee on Standards in the House of Commons, although where such changes are substantial they are put by the Committee to the House for approval before being implemented. Complaints Complaints, whether from Members, the public or anyone else alleging that a journalist is in breach of the rules governing the Register, should in the first instance be sent to the Registrar of Members’ Financial Interests in the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Where possible the Registrar will seek to resolve the complaint informally. In more serious cases the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards may undertake a formal investigation and either rectify the matter or refer it to the Committee on Standards. -

Annual Report 2017 Talktalk Telecom Group PLC Talktalk Is the UK’S Leading Value for Money Connectivity Provider

TalkTalk Telecom Group PLC Group Telecom TalkTalk Annual Report2017 2017 Annual Report 2017 TalkTalk Telecom Group PLC TalkTalk is the UK’s leading value for money connectivity provider� Our mission is to deliver simple, affordable, reliable and fair connectivity for everyone� Stay up to date at talktalkgroup.com Contents Strategic report Corporate governance Financial statements Highlights ������������������������������������������������������������������������ 01 Board of Directors and PLC Committee ������������� 32 Independent auditor’s report �������������������������������� 66 At a glance ���������������������������������������������������������������������� 02 Corporate governance ���������������������������������������������� 36 Consolidated income statement �������������������������� 73 Chairman’s introduction ������������������������������������������ 04 Audit Committee report ������������������������������������������� 41 Consolidated statement of comprehensive FY17 business review ������������������������������������������������� 05 Directors’ remuneration report ����������������������������� 44 income ���������������������������������������������������������������������������� 74 Business model and strategy ��������������������������������� 08 Directors’ report ���������������������������������������������������������� 63 Consolidated balance sheet ����������������������������������� 75 Measuring our performance ����������������������������������� 12 Directors’ responsibility statement ��������������������� 65 Consolidated -

Talktalk Telecom Group Limited Annual Report 2021 1 STRATEGIC REPORT Our Business Model

TalkTalk Telecom Group Limited 2021 Annual Report 2021 Annual Limited Group Telecom TalkTalk 2021 ANNUAL REPORT TalkTalk Telecom Group Limited (formerly TalkTalk Telecom Group PLC) At a glance Contents Strategic report IFC At a glance 2 Our business model 4 Our strategy 6 Key performance indicators 8 Business and financial review 13 Principal risks and uncertainties HQ 18 Section 172 Salford, Greater 24 Regulatory environment Manchester 26 Corporate social responsibility Corporate governance 30 Corporate governance 35 Audit Committee report 38 Directors’ remuneration report 53 Directors’ report 55 Directors’ responsibility statement 47,300 Financial statements Over 3,000 high-speed unbundled 56 Independent auditor’s report Ethernet 66 Consolidated income statement exchanges 67 Consolidated balance sheet connections 68 Consolidated cash flow statement 69 Consolidated statement of changes in equity 70 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 108 Company balance sheet 109 Company cash flow statement 110 Company statement of changes in equity 111 Notes to the Company financial statements Other information UK’s 116 Five year record (unaudited) 96% largest 117 Alternative performance measures population wholesale 118 Glossary coverage broadband 120 Registered office 120 Advisers provider Over 957 million GB average 4 million customer broadband downloads per customers month Stay up to date at www.talktalkgroup.com 2,019 2.8 million employees FTTC and FTTP (as at 28 customers February 2021) WHO WE ARE TalkTalk is the UK’s leading value for money connectivity provider. We believe that simple, affordable, reliable and fair connectivity should be available to everyone. Since entering the market in the early 2000s, we have a proud history as an innovative challenger brand ensuring customers benefit from more choice, affordable prices and better services. -

DICE Best Practice Guide.Pdf

BEST PRACTICE GUIDE Interactive Service, Frequency Social Business Migration, Policy & Platforms Acceptance Models Implementation Regulation & Business Opportunities BEST PRACTICE GUIDE FOREWORD As Lead Partner of DICE I am happy to present this We all want to reap the economic benefi ts of dig- best practice guide. Its contents are based on the ital convergence. The development and successful outputs of fi ve workgroups and countless discus- implementation of new services need extended sions in the course of the project and in conferences markets, however; markets which often have to be and workshops with the broad participation of in- larger than those of the individual member states. dustry representatives, broadcasters and political The sooner Europe moves towards digital switcho- institutions. ver the sooner the advantages of released spectrum can be realised. The DICE Project – Digital Innovation through Co- operation in Europe – is an interregional network We have to recognise that a pan-European telecom funded by the European Commission. INTERREG as and media industry is emerging. The search for an EU community initiative helps Europe’s regions economies of scale is driving the industry into busi- form partnerships to work together on common nesses outside their home country and to strategies projects. By sharing knowledge and experience, beyond their national market. these partnerships enable the regions involved to develop new solutions to economic, social and envi- It is therefore a pure necessity that regional political ronmental challenges. institutions look across the border and aim to learn from each other and develop a common under- DICE focuses on facilitating the exchange of experi- standing. -

LTE Interference Into Domestic Digital Television Systems

Page 1 of 132 Business Unit: Cobham Technical Services ERA Technology RF and EMC Group Report Title: LTE Interference into Domestic Digital Television Systems Author(s): Bal Randhawa Ian Parker Samuel Antwi Client: Ofcom Client Reference: Graham Warren Report Number: 2010-0026 (Issue 2) Project Number: 7A0513004 Report Version: Final Report Report Checked by: Approved by: S Munday M Ganley Head of RF Assessment Head of RF & EMC Group January 2010 Ref. SPM/vs/62/05130/Rep-6537 Cobham Technical Services ERA Technology Report 2010-0026 (Issue 2) © Copyright ERA Technology Limited 2010 All Rights Reserved No part of this document may be copied or otherwise reproduced without the prior written permission of ERA Technology Limited. If received electronically, recipient is permitted to make such copies as are necessary to: view the document on a computer system; comply with a reasonable corporate computer data protection and back-up policy and produce one paper copy for personal use. DOCUMENT CONTROL If no restrictive markings are shown, the document may be distributed freely in whole, without alteration, subject to Copyright. ERA Technology Limited trading as Cobham Technical Services Cleeve Road Leatherhead Surrey KT22 7SA, England Tel : +44 (0) 1372 367000 Fax: +44 (0) 1372 367099 E-mail: [email protected] Read more about Cobham Technical Services on our Internet page at: www.cobham.com/technicalservices Ref: P:\Projects Database\Ofcom 2009 - 7x 05130\Ofcom - 7A0513004 - LTE UMTS mobile interference\ERA Reports\Rep-6537 - 2010-0026 (Issue 2).doc 2 © ERA Technology Ltd Cobham Technical Services ERA Technology Report 2010-0026 (Issue 2) Summary As part of the Digital Dividend Review (DDR), Ofcom commissioned Cobham Technical Services – ERA Technology to carry out a measurement study in order to answer the following questions: 1. -

Cover Sheet for Response to an Ofcom Consultation BASIC DETAILS

Cover sheet for response to an Ofcom consultation BASIC DETAILS Consultation title: Draft Annual Plan 2014/15 To (Ofcom contact): Puja Kalaria Name of respondent: Richard Lindsay-Davies Representing (self or organisation/s): Digital TV Group Address (if not received by email): CONFIDENTIALITY Please tick below what part of your response you consider is confidential, giving your reasons why X Nothing Name/contact details/job title Whole response Organisation Part of the response If there is no separate annex, which parts? If you want part of your response, your name or your organisation not to be published, can Ofcom still publish a reference to the contents of your response (including, for any confidential parts, a general summary that does not disclose the specific information or enable you to be identified)? DECLARATION I confirm that the correspondence supplied with this cover sheet is a formal consultation response that Ofcom can publish. However, in supplying this response, I understand that Ofcom may need to publish all responses, including those which are marked as confidential, in order to meet legal obligations. If I have sent my response by email, Ofcom can disregard any standard e-mail text about not disclosing email contents and attachments. Ofcom seeks to publish responses on receipt. If your response is non-confidential (in whole or in part), and you would prefer us to publish your response only once the consultation has ended, please tick here. Name Richard Lindsay-Davies Signed (if hard copy) DTG response to: Ofcom “Draft Annual Plan 2014/15 Friday 14 February 2014 Ofcom: Draft Annual Plan 2014/15 The Digital TV Group (DTG) welcomes the opportunity to respond to the above consultation regarding Ofcom’s draft proposals for their priorities and work areas in the financial year 2014/15. -

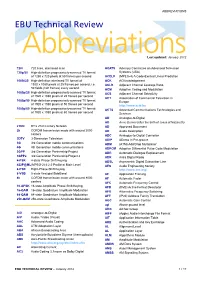

ABBREVIATIONS EBU Technical Review

ABBREVIATIONS EBU Technical Review AbbreviationsLast updated: January 2012 720i 720 lines, interlaced scan ACATS Advisory Committee on Advanced Television 720p/50 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format Systems (USA) of 1280 x 720 pixels at 50 frames per second ACELP (MPEG-4) A Code-Excited Linear Prediction 1080i/25 High-definition interlaced TV format of ACK ACKnowledgement 1920 x 1080 pixels at 25 frames per second, i.e. ACLR Adjacent Channel Leakage Ratio 50 fields (half frames) every second ACM Adaptive Coding and Modulation 1080p/25 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format ACS Adjacent Channel Selectivity of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 25 frames per second ACT Association of Commercial Television in 1080p/50 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format Europe of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 50 frames per second http://www.acte.be 1080p/60 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format ACTS Advanced Communications Technologies and of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 60 frames per second Services AD Analogue-to-Digital AD Anno Domini (after the birth of Jesus of Nazareth) 21CN BT’s 21st Century Network AD Approved Document 2k COFDM transmission mode with around 2000 AD Audio Description carriers ADC Analogue-to-Digital Converter 3DTV 3-Dimension Television ADIP ADress In Pre-groove 3G 3rd Generation mobile communications ADM (ATM) Add/Drop Multiplexer 4G 4th Generation mobile communications ADPCM Adaptive Differential Pulse Code Modulation 3GPP 3rd Generation Partnership Project ADR Automatic Dialogue Replacement 3GPP2 3rd Generation Partnership -

1152/8/3/10 (IR) British Sky Broadcasting Limited

Neutral citation [2014] CAT 17 IN THE COMPETITION Case Number: 1152/8/3/10 APPEAL TRIBUNAL (IR) Victoria House Bloomsbury Place 5 November 2014 London WC1A 2EB Before: THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE ROTH (President) Sitting as a Tribunal in England and Wales B E T W E E N : BRITISH SKY BROADCASTING LIMITED Applicant -v- OFFICE OF COMMUNICATIONS Respondent - and - BRITISH TELECOMMUNICATIONS PLC VIRGIN MEDIA, INC. THE FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION PREMIER LEAGUE LIMITED TOP-UP TV EUROPE LIMITED EE LIMITED Interveners Heard in Victoria House on 23rd July 2014 _____________________________________________________________________ JUDGMENT (Application to Vary Interim Order) _____________________________________________________________________ APPEARANCES Mr. James Flynn QC, Mr. Meredith Pickford and Mr. David Scannell (instructed by Herbert Smith Freehills LLP) appeared for British Sky Broadcasting Limited. Mr. Mark Howard QC, Mr. Gerry Facenna and Miss Sarah Ford (instructed by BT Legal) appeared for British Telecommunications PLC. Mr. Josh Holmes (instructed by the Office of Communications) appeared for the Respondent. EE Limited made written submissions by letter dated 9 May 2014 but did not seek to make oral representations at the hearing. Note: Excisions in this judgment (marked “[…][ ]”) relate to commercially confidential information: Schedule 4, paragraph 1 to the Enterprise Act 2002. 2 INTRODUCTION 1. On 31 March 2010, the Office of Communications (“Ofcom”) published its “Pay TV Statement.” By the Pay TV Statement, Ofcom decided to vary, pursuant to s. 316 of the Communications Act 2003 (“the 2003 Act”), the conditions in the broadcasting licences of British Sky Broadcasting Ltd (“Sky”) for what have been referred to as its “core premium sports channels” (or “CPSCs”), Sky Sports 1 and Sky Sports 2 (“SS1&2”). -

UK Superfast Broadband Projects Directory 2014: Crunch Year for Superfast UK

UK Superfast Broadband Projects Directory 2014: crunch year for Superfast UK Prepared by: Annelise Berendt Date: 14 February 2014 Version: 1.0 Point Topic Ltd 73 Farringdon Road London EC1M 3JQ, UK Tel. +44 (0) 20 3301 3305 Email [email protected] Point Topic – UK Plus report – 2014: crunch year for Superfast UK Contents 1. Background 4 2. Introduction 5 3. The service provider picture 8 4. BT Group puts another £50m into the pot 11 4.1 Fibre on Demand developments 11 4.2 Self-install getting closer 12 4.3 Multicast for GEA launched for TV provision 12 4.4 Cornwall passes target and begins to impact local economy 13 4.5 Northern Ireland FTTC network has over 150,000 customers 13 4.6 BT looks to raise its MDU game 14 4.7 Last batch of 19 exchanges quietly announced 14 4.8 BT Retail sees strong fibre-based growth 16 5. Virgin Media increases the speed stakes 17 5.1 Higher speed services and boosts for existing customers 17 5.2 Virgin acquires Smallworld Fibre 17 6. Altnets move into make or break year 18 6.1 CityFibre floats on AIM 18 6.2 Gradwell launches GigaBath based on CityFibre infrastructure 19 6.3 IFNL continues to build homes passed numbers 20 6.4 Hyperoptic launches in Olympic Village 20 6.5 Venus welcomes Connection Voucher Scheme 21 6.6 Community Fibre in Westminster pilot 21 6.7 Velocity1 uses Wembley to showcase the bigger picture 21 6.8 Call Flow Solutions continues private and publicly-funded rollout 22 6.9 Fibre Options seeing increasing developer interest 22 6.10 Gigaclear continues to grow rural footprint 23 6.11 B4RN sticks to its coverage plans 23 6.12 Cybermoor FTTP services go live 24 6.13 LonsdaleNET launches fibre network in Cumbria 24 6.14 TripleConnect in Cumbrian new build fibre deployment 25 6.15 KC fibre connections approach 7,000 lines 25 6.16 The closure of Digital Region 26 6.17 Student fibre sector is a springboard for the wider market 27 Page 2 of 37 Point Topic – UK Plus report – 2014: crunch year for Superfast UK 7. -

Managing the Effects of 700Mhz Clearance on PMSE and DTT Viewers”

YouView British Telecommunications TalkTalk Group Ofcom call for inputs: “Managing the effects of 700MHz clearance on PMSE and DTT viewers” YouView, BT and TalkTalk are aligned in the responses to this call for input. Minimising disruption to existing DTT consumption, and avoiding a sense of panic at the potential loss of DTT channels – and therefore DTT platform churn - through clear communication and structured consumer support is vital in making the 700MHz clearance a success for DTT consumers. We feel a well-funded information and financial support scheme for 700MHz clearance could minimise platform churn, and ensure homes continue to benefit from free to air DTT reception. Managing expectations in a clear, concise and repeatable manner; supporting consumers end to end, financial support, and minimising disruption should be the goals of the clearance programme. We regard clearance and coexistence as different phases of the same 700MHz programme. We recommend a coordinated approach across the two phases to ensure the both are handled in the same open, informative manner with visible trials and rollout plans, allowing proactive consumer support preparation and seamless communication. 1 YouView British Telecommunications TalkTalk Group Question 1: Do you agree with our assessment of the number of viewers that will need to retune? We believe the assessment is closer to 20 million within the 14-20 million range given: a) The number of DTT television sets and set-to-boxes in each UK home serving as primary, secondary, or even tertiary units. -

Communications Bill (Volume II)

Communications Bill (Volume II) The Bill is divided into two volumes. Volume I contains Clauses 1 to 355. Volume II contains Clauses 356 to 403 and the Schedules. CONTENTS PART 1 FUNCTIONS OF OFCOM Transferred and assigned functions 1 Functions and general powers of OFCOM 2 Transfer of functions of pre-commencement regulators General duties in carrying out functions 3 General duties of OFCOM 4 Duties for the purpose of fulfilling Community obligations 5 Directions in respect of networks and spectrum functions 6 Duties to review regulatory burdens 7 Duty to carry out impact assessments 8Duty to publish and meet promptness standards 9 Secretary of State’s powers in relation to promptness standards Media literacy 10 Duty to promote media literacy OFCOM’s Content Board 11 Duty to establish and maintain Content Board 12 Functions of the Content Board Functions for the protection of consumers 13 Consumer research 14 Duty to publish and take account of research 15 Consumer consultation 16 Membership etc. of the Consumer Panel 17 Committees and other procedure of the Consumer Panel 18 Power to amend remit of Consumer Panel HL Bill 41 53/2 iv Communications Bill International matters 19 Representation on international and other bodies 20 Directions for international purposes in respect of broadcasting functions General information functions 21 Provision of information to the Secretary of State 22 Community requirement to provide information 23 Publication of information and advice for consumers etc. Employment in broadcasting 24 Training and equality of opportunity Charging 25 General power to charge for services Guarantees 26 Secretary of State guarantees for OFCOM borrowing Provisions supplemental to transfer of functions 27 Transfers of property etc.