Food Security and Emergency Markets Mapping and Analysis Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of South Sudan EARLY WARNING and DISEASE

Early Warning and Disease Surveillance System Republic of South Sudan EARLY WARNING AND DISEASE SURVEILLANCE BULLETIN (IDP CAMPS AND COMMUNITIES) Week 48 24 – 30 November 2014 General Overview Completeness for weekly reporting decreased from 98% to 92% while timeliness decreased from 72% to 50% in week 48 when compared to week 47. Malaria remains the top cause of morbidity in week 48 with Malakal PoC having the highest incidence followed by Tongping, Bentiu, Bor and Lankien. During week 48, Malakal PoC had the highest incidence for malaria and ABD, while Bentiu PoC had the highest incidence for ARI and AWD. A total of three suspect measles cases were reported from Melut (1 case) and Lankien (2 cases) during week 48. There are no new HEV cases reported since week 47. The cumulative for HEV in Mingkaman remains at 124 cases including four deaths (CFR 3.23%). There are no new cholera cases reported since week 47. The cumulative remains at 6,421 cholera cases including 167 deaths (CFR 2.60%) from 16 counties in South Sudan. The under-five and crude mortality rates in all IDP sites were below the emergency threshold in week 48. Seven suspect meningitis deaths have been reported from Chotbora PHCC in Longechuk County. The preliminary verification report indicates no new suspect cases since 18 November 2014. Completeness and Timeliness of Reporting Completeness for weekly reporting decreased from 48 (98%) in week 47, to 46 (92%) in week 48. Timeliness for weekly reporting decreased from 35 (72%) in week 47 to 25 (50%) in week 48. -

Upper Nile State SOUTH SUDAN

COMMUNITY CONSULTATION REPORT Upper Nile State SOUTH SUDAN Bureau for Community Security South Sudan Peace and Small Arms Control and Reconciliation Commission United Nations Development Programme Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands The Bureau for Community Security and Small Arms Control under the Ministry of Interior is the Gov- ernment agency of South Sudan mandated to address the threats posed by the proliferation of small arms and community insecurity to peace and development. The South Sudan Peace and Reconciliation Commission is mandated to promote peaceful co-existence amongst the people of South Sudan and advises the Government on matters related to peace. The United Nations Development Programme in South Sudan, through the Community Security and Arms Control Project, supports the Bureau strengthen its capacity in the area of community security and arms control at the national, state and county levels. The consultation process was led by the Government of South Sudan, with support from the Govern- ment of the Netherlands’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Cover photo: A senior chief from Upper Nile. © UNDP/Sun-ra Lambert Baj COMMUNITY CONSULTATION REPORT Upper Nile State South Sudan Published by South Sudan Bureau for Community Security and Small Arms Control South Sudan Peace and Reconciliation Commission United Nations Development Programme MAY 2012 JUBA, SOUTH SUDAN CONTENTS Acronyms ........................................................................................................................... i Foreword .......................................................................................................................... -

Jonglei Unity Upper Nile

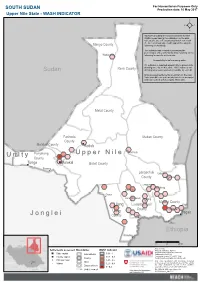

For Humanitarian Purposes Only SOUTH SUDAN Production date: 10 May 2017 Upper Nile State - WASH INDICATOR REACH calculated the areas more likely to have WASH needs basing the estimation on the data collected between February and March 2017 with the Area of Knowledge (AoK) approach, using the Manyo County following methodology. The indicator was created by averaging the percentages of key informants (KIs) reporting on the Wadakona following for specific settlements: - Accessibility to safe drinking water 0% indicates a reported impossibility to access safe Renk County drinking water by all KIs, while 100% indicates safe Sudan drinking water was reported accessible by each KI. Only assessed settlements are shown on the map. Values for different settlements have been averaged and represented with hexagons 10km wide. Melut County Fashoda Maban County County Malakal County Kodok Panyikang Guel Guk Ogod U p p e r N i l e U n i t y County Tonga Malakal Baliet County Pakang Longochuk Udier County Chotbora Longuchok Mathiang Kiech Kon Dome Gum (Kierwan) Mading Maiwut County Ulang Luakpiny/Nasir Kigili County Maiwut Ulang Pagak J o n g l e i County Jikmir Jikou Ethiopia Wanding Sudan 0 25 50 km Data sources: Ethiopia Settlements assessed Boundaries WASH indicator Thematic indicators: REACH Administrative boundaries: UNOCHA; State capital International 0.81 - 1 Settlements: UNOCHA; County capital 0.61 - 0.8 Coordinate System:GCS WGS 1984 C.A.R. County Contact: [email protected] Principal town 0.41 - 0.6 Note: Data, designations and boundaries contained Juba State Village 0.21 - 0.4 on this map are not warranted to be error-free and do not imply acceptance by the REACH partners, Disputed area associates, donors or any other stakeholder D.R.C. -

Marking Nuer Histories

Marking Nuer Histories Gender, Gerontocracy, and the Politics of Inclusion in the Upper Nile from 1400 – 1931 By Noel Stringham Department of History University of Virgnia 1 February 2016 0 Table of Contents Table of Contents Page 1 Dating System Table of Historical Age-Sets/Marriage-Sets Page 2 List of Maps Page 4 Orthographies, Spellings, and Translations Page 5 Acknowledgements Page 8 Introduction Marking the Past: Page 10 Indigenous Epistemologies of History, “the Nuer”, and Africanist Historians Chapter 1 History as Exogamous Kinship: Page 33 Agro-Pastoralist Mobility, Pulling Teeth, and Ethnogenesis After 1400 Chapter 2 Marking Marriageability: Page 76 Reconstructing a Gendered History of the Era of “Turning-Hearts (1790s – 1828) Chapter 3 Marking Costly Assimilations Page 110 Loosing Battles, Recruiting Bachelors, and Erosion of Moral Community (1828 – 1860s) Chapter 4 Marking the Prophet’s Rod: Page 154 From Chaos to Syncretistic Community (1870s – 1896) Chapter 5 Marking Militarization: Page 196 From the Prophet’s Rod to Firearms on the Abyssinian Frontier (1896 – 1920s) Conclusion History as Additive: Page 245 Achieving and Archiving Change through Combination and Accumulation Bibliography Page 253 1 Table of Historic Age-Sets / Marriageability-Sets Cohorts of the Eastern Jikäny and other nei ti naath until 2003 Ric (thok naath) Age-Set / Marriage-Set Name (English) Initiation Date - Early Sets (Bul and Jikäny) 1 – Riɛk 2 Alter Pole Unknown Jɔk 3 Earth-Spirit / Disease Unknown - Sets with Gaar (Jikäny, Lak, Thiaŋ, Jagɛi, Lɔu, -

Republic of South Sudan 2015 Table A

Republic of South Sudan 2015 Table A: Total funding and outstanding pledges* as of 24 September 2021 http://fts.unocha.org (Table ref: R10) Compiled by OCHA on the basis of information provided by donors and appealing organizations. Donor Channel Description Funding Outstanding Pledges USD USD African Development Bank WFP To be allocated to a specific sector/projects 1,000,000 0 Allocation of unearmarked funds by SC Strengthen and enhanced coverage of nutrition services with a 300,000 0 IOM focus on local capacity building, quality service provision and increased surveillance in the conflict and vulnerable populations in South Sudan Allocation of unearmarked funds by UNFPA Ensuring Availability of Life Saving Reproductive Health 1,151,689 0 UNFPA Commodities and Supplies to provide Reproductive Health (RH) services for IDPs, Returnees, Refugees and other Vulnerable Populations in South Sudan Allocation of unearmarked funds by IOM Provision of WASH Assistance to Sudanese Refugees in Doro 221,847 0 UNHCR camp, Maban County, Upper Nile State, South Sudan Allocation of unearmarked funds by Samaritan's Purse Provision of emergency WASH, nutrition, and secondary 1,300,000 0 UNHCR healthcare services for refugees living in Pariang and Maban Counties Allocation of unearmarked funds by IOM Humanitarian Common Logistics Services in the Republic of 1,232,392 0 WFP South Sudan Allocation of unearmarked funds by WFP To be allocated to a specific sector/projects (Multilateral)) 1,284,000 0 WFP Allocation of unearmarked funds by WFP To be allocated to a specific sector/projects (Multilateral)) 14,766,001 0 WFP Allocation of unearmarked funds by WFP To be allocated to a specific sector/projects (Multilateral)) 22,721,352 0 WFP Allocation of unearmarked funds by CMA Strengthening the capacity of primary health care facilities to 55,417 0 WHO deliver essential and emergency services in Fangak and Nyirol counties of Jonglei State. -

Secretary-General's Report on South Sudan

United Nations S/2020/145 Security Council Distr.: General 26 February 2020 Original: English Situation in South Sudan Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 2459 (2019), by which the Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) until 15 March 2020 and requested me to report on the implementation of the Mission’s mandate every 90 days. It covers political and security developments between 1 December 2019 and 15 February 2020, the humanitarian and human rights situation and progress made in the implementation of the Mission’s mandate. II. Political and economic developments Key political updates 2. During the reporting period, the President of South Sudan, Salva Kiir, and the leader of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army in Opposition (SPLM/A-IO), Riek Machar, held several face-to-face meetings in Juba. The principals deliberated on outstanding pre-transitional tasks, including transitional security arrangements and the issue of states and their boundaries. Although the status of Mr. Machar remains unresolved, he travelled to Juba from 10 to 17 December and from 14 to 26 January, accompanied on both occasions by the Vice-President of the Sovereign Council of the Sudan, Lieutenant General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo. 3. A key outstanding issue is the determination of the number of states and their boundaries. From 2 to 4 December, the Deputy President and Special Envoy of South Africa to South Sudan, David Mabuza – supported by the Special Envoys of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), Kenya, the Sudan and Uganda – convened deliberations on the matter, but was unable to get the parties to reach a consensus. -

Third Party Monitoring of the World Bank Rapid Results Health Project Final Report

Third Party Monitoring of the World Bank Rapid Results Health Project Final Report 1 / 17 Abbreviations BPHNS: Basic Package of Health and Nutrition Services CH: County Hospital CHD: County Health Department CMA: Christian Mission Aid CMD: Christian Mission for Development CO: Clinical Officer CPA: Comprehensive Peace Agreement FGD: Focus Group Discussions GO: Government GoSS: Government of the Republic of South Sudan (GoSS) HL: Health Link HPF: Health Pooled Fund IMA: IMA World Health IMC: International Medical Corps IO: In-Opposition IOM: International Organisation for Migration IP: Implementing Partner KII: Key Informant Interview LGSDP: Local Governance and Service Delivery Project. MoH: Ministry of Health NGO: Non-Governmental Organisation PHC: Primary Health Care PHCC: Primary Health Care Centre PHCU: Primary Health Care Unit PIU: Project Implementation Unit RRHP: Rapid Results Health Project SGBV: Sexual and Gender Based Violence SMC: Sudan Medical Care SSAID: South Sudan Agency for Internal Development UNKEA: Universal Network for Knowledge and Empowerment Agency WB: World Bank WV: World Vision TPM: Third Party Monitoring 2 / 17 Executive Summary and Findings 1. Introduction The World Bank’s portfolio for South Sudan contains a number of International Development Association’s (IDA) investment projects aimed at improving local governance and service delivery. Although the World Bank (WB) has put in place measures to mitigate political security and fiduciary risks, there remains a gap in managing operational risk in terms of monitoring and evaluation of its investment projects in South Sudan following the resumption of armed conflict in 2013. Due to its strong operational capacity and presence in South Sudan, WB contracted the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in June 2018 to implement Third Party Monitoring (TPM) activities of its Rapid Results Health Project (RRHP) currently being implemented in former Upper Nile State and Jonglei State, and the Local Government and Service Delivery Project (LOGOSEED). -

Project Proposal

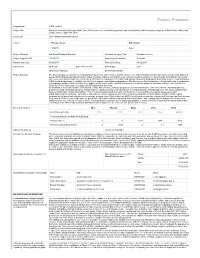

Project Proposal Organization RI (Relief International) Project Title Provision, strengthening and expansion of life saving community and facility based nutrition services in Longochuk and Maban Counties in Upper Nile State Fund Code SSD15/HSS10/SA2/N/INGO/517 Cluster Primary cluster Sub cluster NUTRITION None Project Allocation 2nd Round Standard Allocation Allocation Category Type Frontline services Project budget in US$ 200,000.00 Planned project duration 5 months Planned Start Date 01/08/2015 Planned End Date 31/12/2015 OPS Details OPS Code SSD15/H/73004/R OPS Budget 0.00 OPS Project Ranking OPS Gender Marker Project Summary According to the South Sudan Humanitarian Response Plan 2015 MidYear Update, Longechuk and Maban are classified as highly vulnerable due to critical unmet needs and access constraints. Both counties have reported emergency levels of global acute malnutrition (GAM), and high mortality and morbidity rates. The dire health and nutrition situation is aggravated by emergency and crisis levels of food insecurity, and restricted humanitarian access as a result of conflict and weather constraints. In May 2015, RI conducted a rapid SMART nutrition survey in Upper Nile, which revealed a GAM prevalence of 18.9 percent (12.5 27.5) and a severe acute malnutrition (SAM) rate of 7.1 percent in Longechuk. Similarly, in Maban, the prevalence of GAM and SAM stood at 11.7 percent and 4.7 percent, respectively. The nutritional situation is likely worse in areas which were not able to be accessed due to flooding, insecurity and distance. Given the situation, there is an urgent need to expand and integrate SC, OTP, TSFP and IYCF support and promotion services with primary health care (PHC) facilities. -

Introduction Situation Overview: Upper Nile State, South Sudan

Situation Overview: Upper Nile State, South Sudan July-August 2017 Introduction SUDAN SUDAN at the time, mainly in the south-eastern portion of the state (Maiwut, Longochuk, Nasir, Ulang), Between July and August 2017, the revival of MANYO MANYO which facilitates the provision of information conflict and increased insecurity has disrupted RENK RENK from these areas which are known to have livelihoods, access to services and humanitarian access difficulties and information gaps at assistance in Upper Nile state. Moreover, the moment. However, the central part of the insecurity has caused further displacement MELUT MELUT state (Maban, Melut, Baliet, Renk) was not into Ethiopia and Sudan with continued internal assessed and the western bank had only FASHODA MABAN FASHODA MABAN displacement inside Upper Nile State. one county where over 5% of all settlements MALAKAL MALAKAL To inform the response of humanitarian actors PANYIKANG BALIET PANYIKANG BALIET were assessed (Fashoda). In August, REACH working outside of formal displacement sites, LONGOCHUK LONGOCHUK interviewed KIs from all 12 counties. However, LUAKPINY/ LUAKPINY/ only three counties exceeded a 5% settlement REACH has been conducting an ongoing NASIR NASIR assessment of hard-to-reach areas in South ULANG MAIWUT ULANG MAIWUT coverage in the western bank of the Nile Sudan since 2015, for which data on settlements (Manyo, Fashoda and Panyikang) and one across Greater Upper Nile, Greater Equatoria county in the south-eastern part of the state and Western Bahr el Ghazal region is collected Assessed settlements (Maiwut). Given this geographical shift in areas on a monthly basis. ettlement covered between July and August this report Cover ercentage of assessed settlements relative to the CHA (CD) total dataset: does not purport to study trends between July Between July and August 2017, REACH Map 1:0 REACH assessment coverage of Upper Nile State, July 2017 (left), August (right). -

GOAL EMR062.16 Report

Final Report Presented to the Isle of Man Government Provision of essential supplies to support lifesaving humanitarian assistance for conflict affected and displaced populations in Upper Nile State, South Sudan A supply delivery in Ulang County Introduction Humanitarian needs in South Sudan are at their highest since the December 2013 conflict that led three million to flee their homes as IDPs or refugees to neighbouring countries. The conflict in South Sudan is showing little sign of abating. In 2016, the humanitarian crisis in South Sudan deepened and spread, affecting people in areas previously considered stable and exhausting the coping capacity of those already impacted. The Humanitarian Needs Overview estimated that nearly 7.5 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance and protection across the country as per the end of 2016, as a result of armed conflict, inter-communal violence, economic crisis, disease outbreaks and climatic shocks. The government of the Isle of Man supported GOAL with a £20,000 grant to provide vital and life-saving health and nutrition programming to vulnerable and conflict-affected populations of Melut, Maiwut and Ulang Counties, Upper Nile State. Project Aim This project aimed at providing lifesaving humanitarian assistance to conflict-affected and displaced populations in Upper Nile State, South Sudan. Project Objectives This project intended to deliver supplies to GOAL field sites in Upper Nile State. Programmatic and operational supplies stored in GOAL warehouse in Juba needed to be urgently airlifted to Melut, Maiwut and Ulang Counties in order to avoid any supply chain Melut rupture, especially for drugs and food commodities needed for primary health care facilities and nutrition services. -

Project Proposal

Project Proposal Organization GOAL (GOAL) Project Title Provision of integrated Primary Health Care (PHC) services for vulnerable populations and strengthening health emergency response in Baliet, Melut, Maiwut and Ulang Counties, Upper Nile State. Fund Code SSD15/HSS10/SA2/H/INGO/528 Cluster Primary cluster Sub cluster HEALTH None Project Allocation 2nd Round Standard Allocation Allocation Category Type Frontline services Project budget in US$ 225,000.00 Planned project duration 5 months Planned Start Date 01/08/2015 Planned End Date 31/12/2015 OPS Details OPS Code SSD15/H/73107/R OPS Budget 0.00 OPS Project Ranking OPS Gender Marker Project Summary The project proposes to provide an integrated package of care which focuses on both curative care and communitybased health activities to internally displaced people (IDPs) in Melut and Ulang Counties, Upper Nile State. GOAL is currently the lead (and only) healthcare partner in Ulang County, providing primary health care services to IDPs through four emergency health facilities. Following recent conflict and widespread looting and property destruction in Melut Town and Akoka, GOAL began preparations to establish new facilities to support newly displaced populations. One emergency clinic is planned to relocate to Koradar to support the IDP population displaced from Rom IDP area, and two mobile clinics will be established in Paloich to reach the displaced population of Melut Town. Activities at Dethoma II PHCC will continue to support the IDP population at this camp. Health facilities will provide curative consultations, routine and outreach expanded programme of immunisation (EPI), maternal healthcare and family planning, growth screening, and health education. -

Humanitarian Needs Overview South Sudan Issued November 2019

HUMANITARIAN HUMANITARIAN PROGRAMME CYCLE 2020 NEEDS OVERVIEW ISSUED NOVEMBER 2019 SOUTH SUDAN About This document is consolidated by OCHA on behalf of the Humanitarian Country Team and partners. It provides a shared understanding of the crisis, including the most pressing humanitarian need and the estimated number of people who need assistance. It represents a consolidated evidence base and helps inform joint strategic response planning. The administrative boundaries and names shown and designations used on this map and subsequent maps and tables in the document do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determimed. Final status of Abyei area is not determined. Manyo SUDAN Renk Melut Fashoda Maban ABYEI Panyijiar UPPER NILE REGION Panyikang Malakal Abiemnhom UNITY Baliet Aweil North Aweil Rubkona East Mayom Guit Canal/Pigi Longochuk Twic Fangak Aweil West Gogrial Luakpiny/ East Nasir Raja NORTHERN Aweil Gogrial West Koch Maiwut BAHR EL South Nyirol Ulang Tonj GHAZAL North Ayod Aweil Centre Mayendit WARRAP Leer Tonj ETHIOPIA East WESTERN Panyijiar JONGLEI Akobo BAHR EL Rumbek Duk Wau Jur North Uror GHAZAL River Cueibet Rumbek Twic East Pochalla Centre Yirol Tonj East South Rumbek East CENTRAL Nagero LAKES Yirol Bor South West Pibor AFRICAN Awerial Wulu REPUBLIC Tambura Mvolo Terekeka WESTERN EQUATORIA Mundri Lafon Kapoeta West Mundri CENTRAL North Kapoeta East Ezo Ibba East EQUATORIA Maridi EASTERN Yambio Juba EQUATORIA Nzara Juba Kapoeta South Lainya Torit Budi Yei Ikotos Kajo-keji Magwi KENYA DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO UGANDA COVER PHOTO: UPPER NILE, SOUTH SUDAN Sandy Chuol, 10 years old, carries a jerry can of water for her family in Malakal town, Upper Nile.