Mauro Salis the Virgin Hodegetria Iconography in the Crown Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Cura Di Antonia Cava 1 3 a Cura Di Antonia Cava 8 1

11381.1_cop 1381.1.13 17/02/20 16:36 Pagina 1 1 A cura di Antonia Cava 1 3 A cura di Antonia Cava 8 1 . IL GIOCO DEL KILLER 1 Questo volume raccoglie i contributi di studiosi provenienti da diversi ambiti disciplinari, A . Il gioco del killer accomunati dall’aver preso parte a un’iniziativa di formazione all’avanguardia ideata da C A Domenico Carzo: il Master “Esperto in intervento sociale minori e mafie”. I saggi proposti V analizzano le culture mafiose e la devianza minorile generando un serrato confronto tra dif - A Culture mafiose e minori ( ferenti prospettive teoriche e di ricerca. Una riflessione interdisciplinare che non solo inter - A preta il tema dei “figli di mafia”, ma esplora anche strategie che possano offrire un’alterna - C U tiva sociale, culturale e affettiva. R A D I Antonia Cava è professore associato di Sociologia dei processi culturali e comunicativi ) I presso il Dipartimento di Scienze Cognitive, Psicologiche, Pedagogiche e Studi Culturali L dell’Università degli Studi di Messina. Insegna Industria culturale e media studies e Sociologia G I della comunicazione e coordina il Master “Esperto in intervento sociale minori e mafie”. O Svolge attività di ricerca su pubblici televisivi, consumi culturali e immaginario mediale. Tra le C O sue pubblicazioni: # Foodpeople. Itinerari mediali e paesaggi gastronomici contemporanei D (Aracne 2018) e Noir Tv. La cronaca nera diventa format televisivo (FrancoAngeli 2013). E L K I L L E R SScienze de ll aCcomunicazione Collana diretta da Marino Livolsi Franc oAngeli ISBN 978-88-917-7285-5 -

Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God George Contis M.D

University of Dayton eCommons Marian Library Art Exhibit Guides Spirituality through Art 2015 Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God George Contis M.D. Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/ml_exhibitguides Recommended Citation Contis, George M.D., "Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God" (2015). Marian Library Art Exhibit Guides. 5. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/ml_exhibitguides/5 This Exhibit Guide is brought to you for free and open access by the Spirituality through Art at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Library Art Exhibit Guides by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God by George Contis, M.D., M.P.H . Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God by George Contis, M.D., M.P.H. Booklet created for the exhibit: Icons from the George Contis Collection Revelation Cast in Bronze SEPTEMBER 15 – NOVEMBER 13, 2015 Marian Library Gallery University of Dayton 300 College Park Dayton, Ohio 45469-1390 937-229-4214 All artifacts displayed in this booklet are included in the exhibit. The Nativity of Christ Triptych. 1650 AD. The Mother of God is depicted lying on her side on the middle left of this icon. Behind her is the swaddled Christ infant over whom are the heads of two cows. Above the Mother of God are two angels and a radiant star. The side panels have six pairs of busts of saints and angels. Christianity came to Russia in 988 when the ruler of Kiev, Prince Vladimir, converted. -

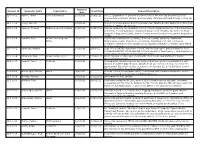

Docenti Scuola Secondaria II Grado Elenco Provvisorio

Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca Ufficio Scolastico Regionale per il Lazio Ufficio VI - Ambito territoriale per la provincia di Roma GRADUATORIA PROVVISORIA DIRITTO ALLO STUDIO ANNO 2020 - SECONDO GRADO data prov. classe rapporto servizio titolo da anzianita' rinnovo fuori laurea ammesso n. nominativo nascita nascitaconcorso sede di servizio lavoro * part-time conseguire ** servizio permessi corso part-time con riserva 1 FARINA SILVIA 23/05/1964 RM A012 IPSEOA ARTUSI A NO A 11 SI NO NO NO 2 CARIATI GIANNI 04/10/1970 CS B016 IIS LUCA PACIOLO A NO A 10 SI NO NO SI 3 PELLE TERESA 04/09/1968 RM A046 I.I.S. CONFALONIERI DE CHIRICO A NO A 8 SI NO NO NO 4 PETRILLO RENATA 06/02/1968 NA A046 L.A. CARAVILLANI A SI A 6 SI NO NO NO 5 ORECCHINI CHIARA 31/01/1981 RM A054 IIS COPERNICO A NO A 4 SI NO NO NO 6 TRAPANNONE ALESSANDRA 17/05/1985 RM B011 I.T.A. EMILIO SERENI A NO A 2 SI NO NO NO 7 OLIVADESE SIMONA 08/11/1982 TO AB24 E. ROSSI B NO A 13 SI NO NO NO 8 IEMMA PIERA 20/04/1965 RC AA24 IIS L. LOMBARDO RADICE B NO A 9 SI NO NO NO 9 TARRA VINCENZA 28/07/1969 CE A046 I.I.S. DE AMICIS-CATTANEO B NO A 8 SI NO NO NO 10 BARBA MADDALENA 30/08/1989 SA B016 I.I.S. "ROSSELLINI" B NO A 7 SI NO NO NO 11 AGNELLO LUCA 14/02/1976 SR A020 I.S.I.S.S. -

Catálogo De Shortlatino ÍNDICE INDEX

European and Latin American short film market Catálogo de Shortlatino ÍNDICE INDEX Bienvenidos / Welcome .................................................... 3 Programa Shortlatino / Shortlatino program ............. 5 PAÍSES EUROPEOS / EUROPEAN COUNTRIES PAÍSES LATINOS / LATIN COUNTRIES Alemania / Germany ........................................................ 11 Argentina / Argentina .................................................. 299 Austria / Austria .............................................................. 40 Brasil / Brazil .................................................................. 303 Bélgica / Belgium ............................................................. 41 Chile / Chile ................................................................... 309 Bulgaria / Bulgaria ......................................................... 49 Colombia / Colombia ...................................................... 311 Dinamarca / Denmark .................................................... 50 Costa Rica / Costa Rica ................................................ 315 Eslovenia / Slovenia ........................................................ 51 Cuba / Cuba ..................................................................... 316 España / Spain ................................................................. 52 México / Mexico ............................................................... 317 Estonia / Estonia ........................................................... 168 Perú / Peru .................................................................... -

Kreinath, Jens. "Aesthetic Sensations of Mary: the Miraculous Icon Of

Kreinath, Jens. "Aesthetic Sensations of Mary: The Miraculous Icon of Meryem Ana and the Dynamics of Interreligious Relations in Antakya." Figurations and Sensations of the Unseen in Judaism, Christianity and Islam: Contested Desires. By Birgit Meyer and Terje Stordalen. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019. 154–171. Bloomsbury Studies in Material Religion. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 26 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350078666.0017>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 26 September 2021, 12:16 UTC. Copyright © Birgit Meyer, Terje Stordalen and Contributors. This Work is licensed under the Creative Commons License. 2019. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 8 Aesthetic Sensations of Mary: Th e Miraculous Icon of Meryem Ana and the Dynamics of Interreligious Relations in Antakya1 J e n s K r e i n a t h Introduction Antakya – formerly Antioch – is the southernmost city of Turkey, known for its religious and ethnic diversity, with its people belonging to diff erent Christian and Muslim denominations. It is situated with the Mediterranean to the west and borders Syria to the east and south (see Figure 8.1 ). In 1939, Hatay was the last province to offi cially become part of the Republic of Turkey ( Shields 2011 : 17–47, 143–75, 232–49). Now, the ethnically diverse population of about 1.5 million is primarily composed of people of Turkish and Arab descent. With its unique blend of diff erent languages and cultures, Hatay became known for its religious tourism industry. -

Maestà (Madonna and Child with Four Angels) C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Master of Città di Castello Italian, active c. 1290 - 1320 Maestà (Madonna and Child with Four Angels) c. 1290 tempera on panel painted surface: 230 × 141.5 cm (90 9/16 × 55 11/16 in.) overall: 240 × 150 × 2.4 cm (94 1/2 × 59 1/16 × 15/16 in.) framed: 252.4 x 159.4 x 13.3 cm (99 3/8 x 62 3/4 x 5 1/4 in.) Samuel H. Kress Collection 1961.9.77 ENTRY This panel, of large dimensions, bears the image of the Maestà represented according to the iconographic tradition of the Hodegetria. [1] This type of Madonna and Child was very popular among lay confraternities in central Italy; perhaps it was one of them that commissioned the painting. [2] The image is distinguished among the paintings of its time by the very peculiar construction of the marble throne, which seems to be formed of a semicircular external structure into which a circular seat is inserted. Similar thrones are sometimes found in Sienese paintings between the last decades of the thirteenth and the first two of the fourteenth century. [3] Much the same dating is suggested by the delicate chrysography of the mantles of the Madonna and Child. [4] Recorded for the first time by the Soprintendenza in Siena c. 1930 as “tavola preduccesca,” [5] the work was examined by Richard Offner in 1937. In his expertise, he classified it as “school of Duccio” and compared it with some roughly contemporary panels of the same stylistic circle. -

Langues, Accents, Prénoms & Noms De Famille

Les Secrets de la Septième Mer LLaanngguueess,, aacccceennttss,, pprréénnoommss && nnoommss ddee ffaammiillllee Il y a dans les Secrets de la Septième Mer une grande quantité de langues et encore plus d’accents. Paru dans divers supplément et sur le site d’AEG (pour les accents avaloniens), je vous les regroupe ici en une aide de jeu complète. D’ailleurs, à mon avis, il convient de les traiter à part des avantages, car ces langues peuvent être apprises après la création du personnage en dépensant des XP contrairement aux autres avantages. TTaabbllee ddeess mmaattiièèrreess Les différentes langues 3 Yilan-baraji 5 Les langues antiques 3 Les langues du Cathay 5 Théan 3 Han hua 5 Acragan 3 Khimal 5 Alto-Oguz 3 Koryo 6 Cymrique 3 Lanna 6 Haut Eisenör 3 Tashil 6 Teodoran 3 Tiakhar 6 Vieux Fidheli 3 Xian Bei 6 Les langues de Théah 4 Les langues de l’Archipel de Minuit 6 Avalonien 4 Erego 6 Castillian 4 Kanu 6 Eisenör 4 My’ar’pa 6 Montaginois 4 Taran 6 Ussuran 4 Urub 6 Vendelar 4 Les langues des autres continents 6 Vodacci 4 Les langages et codes secrets des différentes Les langues orphelines ussuranes 4 organisations de Théah 7 Fidheli 4 Alphabet des Croix Noires 7 Kosar 4 Assertions 7 Les langues de l’Empire du Croissant 5 Lieux 7 Aldiz-baraji 5 Heures 7 Atlar-baraji 5 Ponctuation et modificateurs 7 Jadur-baraji 5 Le code des pierres 7 Kurta-baraji 5 Le langage des paupières 7 Ruzgar-baraji 5 Le langage des “i“ 8 Tikaret-baraji 5 Le code de la Rose 8 Tikat-baraji 5 Le code 8 Tirala-baraji 5 Les Poignées de mains 8 1 Langues, accents, noms -

Estudio Sobre El Contexto Económico De Las Prácticas Audiovisuales Independientes En El Ámbito Artístico Catalán

Estudio sobre el contexto económico de las prácticas audiovisuales independientes en el ámbito artístico catalán: procesos de I+D y nuevos lechos de empleo Diciembre/2009 Estudio realizado por AAVC www.aavc.net (Associació d’Artistes Visuals de Catalunya) con el apoyo de la distribuidora de videoarte HAMACA www.hamacaonline.net y la coordinación de la productora cultural YProductions www.ypsite.net Índice 1. Introducción al objeto de estudio y metodología 3 1.1 Presentación del estudio 4 1.2 Metodología del estudio 6 1.2.1 Equipo investigador 6 1.2.2 Herramientas metodológicas 7 1.2.3 Marco temporal 7 1.2.4 Objeto de estudio 9 2. Aproximación a los perfiles y prácticas del sector 14 2.1 Videoarte 15 2.2 Documental independiente 29 2.3 Animación artística/experimental 38 2.4 Video creación en directo: Veejing y Live Cinema 49 2.5 Performance audiovisual y Videodanza 62 2.6 Cine experimental 70 2.7 Productoras audiovisuales independientes 81 2.8 Plataformas online del audiovisual independiente 94 3. Potencial de Innovación en el audiovisual independiente 113 3.1 Indicadores de Innovación Emergente en el Audiovisual Independiente 114 3.2 La transferencia de conocimiento 117 3.2.1 Áreas beneficiadas por la transferencia 117 3.2.2 Formas de transferencia 119 3.2.3 Conclusiones 123 3.3 Las redes en los procesos de I+D 124 3.3.1 Las redes como forma de trabajo 125 3.3.2 Estructura de las redes en los diferentes ámbitos 126 3.3.3 Redes sociales on-line 129 3.3.4 Conclusiones 129 3.4 La experimentación con nuevas tecnologías y modelos de software libre 131 3.4.1 Cultura Libre en el audiovisual independiente 132 3.4.2 Software libre en el audiovisual independiente 133 3.4.3 Viabilidad económica en proyectos de software libre 135 3.4.4 Conclusiones 137 3.5 Conclusiones 138 4. -

Requests Report

Received Request ID Requester Name Organization Closed Date Request Description Date 12-F-0001 Vahter, Tarmo Eesti Ajalehed AS 10/3/2011 3/19/2012 All U.S. Department of Defense documents about the meeting between Estonian president Arnold Ruutel (Ruutel) and Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney on July 19, 1991. 12-F-0002 Jeung, Michelle - 10/3/2011 - Copies of correspondence from Congresswoman Shelley Berkley and/or her office from January 1, 1999 to the present. 12-F-0003 Lemmer, Thomas McKenna Long & Aldridge 10/3/2011 11/22/2011 Records relating to the regulatory history of the following provisions of the Department of Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS), the former Defense Acquisition Regulation (DAR), and the former Armed Services Procurement Regulation (ASPR). 12-F-0004 Tambini, Peter Weitz Luxenberg Law 10/3/2011 12/12/2011 Documents relating to the purchase, delivery, testing, sampling, installation, Office maintenance, repair, abatement, conversion, demolition, removal of asbestos containing materials and/or equipment incorporating asbestos-containing parts within its in the Pentagon. 12-F-0005 Ravnitzky, Michael - 10/3/2011 2/9/2012 Copy of the contract statement of work, and the final report and presentation from Contract MDA9720110005 awarded to the University of New Mexico. I would prefer to receive these documents electronically if possible. 12-F-0006 Claybrook, Rick Crowell & Moring LLP 10/3/2011 12/29/2011 All interagency or other agreements with effect to use USA Staffing for human resources management. 12-F-0007 Leopold, Jason Truthout 10/4/2011 - All documents revolving around the decision that was made to administer the anti- malarial drug MEFLOQUINE (aka LARIAM) to all war on terror detainees held at the Guantanamo Bay prison facility as stated in the January 23, 2002, Infection Control Standard Operating Procedure (SOP). -

Italian Films (Updated April 2011)

Language Laboratory Film Collection Wagner College: Campus Hall 202 Italian Films (updated April 2011): Agata and the Storm/ Agata e la tempesta (2004) Silvio Soldini. Italy The pleasant life of middle-aged Agata (Licia Maglietta) -- owner of the most popular bookstore in town -- is turned topsy-turvy when she begins an uncertain affair with a man 13 years her junior (Claudio Santamaria). Meanwhile, life is equally turbulent for her brother, Gustavo (Emilio Solfrizzi), who discovers he was adopted and sets off to find his biological brother (Giuseppe Battiston) -- a married traveling salesman with a roving eye. Bicycle Thieves/ Ladri di biciclette (1948) Vittorio De Sica. Italy Widely considered a landmark Italian film, Vittorio De Sica's tale of a man who relies on his bicycle to do his job during Rome's post-World War II depression earned a special Oscar for its devastating power. The same day Antonio (Lamberto Maggiorani) gets his vehicle back from the pawnshop, someone steals it, prompting him to search the city in vain with his young son, Bruno (Enzo Staiola). Increasingly, he confronts a looming desperation. Big Deal on Madonna Street/ I soliti ignoti (1958) Mario Monicelli. Italy Director Mario Monicelli delivers this deft satire of the classic caper film Rififi, introducing a bungling group of amateurs -- including an ex-jockey (Carlo Pisacane), a former boxer (Vittorio Gassman) and an out-of-work photographer (Marcello Mastroianni). The crew plans a seemingly simple heist with a retired burglar (Totó), who serves as a consultant. But this Italian job is doomed from the start. Blow up (1966) Michelangelo Antonioni. -

Religious Imagery of the Italian Renaissance

Religious Imagery of the Italian Renaissance Structuring Concepts • The changing status of the artist • The shift from images and objects that are strictly religious to the idea of Art • Shift from highly iconic imagery (still) to narratives (more dynamic, a story unfolding) Characteristics of Italian Images • Links to Byzantine art through both style and materials • References to antiquity through Greco-Roman and Byzantine cultures • Simplicity and monumentality of forms– clearing away nonessential or symbolic elements • Emphasizing naturalism through perspective and anatomy • The impact of the emerging humanism in images/works of art. TIMELINE OF ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: QUATROCENTO, CINQUECENTO and early/late distinctions. The Era of Art In Elizabeth’s lecture crucifixex, she stressed the artistic representations of crucifixions as distinct from more devotional crucifixions, one of the main differences being an attention paid to the artfulness of the images as well as a break with more devotional presentations of the sacred. We are moving steadily toward the era which Hans Belting calls “the Era of Art” • Artists begin to sign their work, take credit for their work • Begin developing distinctive styles and innovate older forms (rather than copying) • A kind of ‘cult’ of artists originates with works such as Georgio Vasari one of the earliest art histories, The Lives of the Artists, which listed the great Italian artists, as well as inventing and developing the idea of the “Renaissance” Vasari’s writing serves as a kind of hagiography of -

Byzantines Eikones

ΠΕΡΙΕΧΟΜΕΝΑ - CONTENTS ΧΑΡΙΣ ΚΑΛΛΙΓΑ, ΜΑΡΙΑ ΒΑΣΙΛΑΚΗ Πρόλογος 1 HARIS KALUGA, MARIA VASSILAKI Preface 2 ΜΑΡΙΑ ΒΑΣΙΛΑΚΗ Εισαγωγή 3 MARIA VASSILAKI Introduction 6 Βιβλιογραφία - Συντομογραφίες Bibliography - Abbreviations 17 Μέρος Α .· Από την τέχνη και την εικονογραφία των εικόνων Part One: From the Art and Iconography of Icons ENGELINA SMIRNOVA Eleventh-Century Icons from St Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod and the Problem of the Altar Barrier 21 ENGELINA SMIRNOVA Εικόνες του 11ου αιώνα από τον καθεδρικό ναό της Αγίας Σοφίας στο Νόβγκοροντ και το πρόβλημα του τέμπλου 27 TITOS PAPAMASTORAKIS The Display of Accumulated Wealth in Luxury Icons: Gift-giving from the Byzantine Aristocracy to God in the Twelfth Century 35 ΤΙΤΟΣ ΠΑΠΑΜΑΣΤΟΡΑΚΗΣ Επίδειξη συσσωρευμένου πλούτου σε πολυτελείς εικόνες του 12ου αιώνα: η δωροδοσία της βυζαντινής αριστοκρατίας στο Θεό 48 NANCY PATTERSON SEVCENKO Marking Holy Time: the Byzantine Calendar Icons 51 NANCY PATTERSON SEVCENKO Ορίζοντας τον ιερό χρόνο: βυζαντινές εικόνες μηνολογίου 57 OLGA ETINHOF The Virgin of Vladimir and the Veneration of the Virgin of Blachemai in Russia 63 OLGA ETINHOF Η Παναγία του Βλαντιμίρ και η λατρεία της Παναγίας των Βλαχερνών στη Ρωσία 69 JOHN STUART The Deposition of the Virgin's Sash and Robe, the Protection of the Mother of God (Pokrov) and the Blachernitissa 75 JOHN STUART Η κατάθεση της εσθήτος της Θεοτόκου, το εικονογραφικό θέμα του Pokrov και η Βλαχερνήτισσα · 84 MARY ASPRA-VARDAVAKIS Observations on a Thirteenth-Century Sinaitic Diptych Representing St Procopius, the Virgin Kykkotissa