Images of the Mother Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Madonna and Child on a Curved Throne C

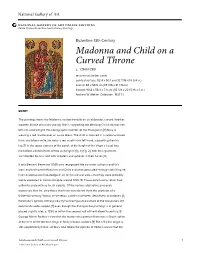

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century Paintings Byzantine 13th Century Madonna and Child on a Curved Throne c. 1260/1280 tempera on linden panel painted surface: 82.4 x 50.1 cm (32 7/16 x 19 3/4 in.) overall: 84 x 53.5 cm (33 1/16 x 21 1/16 in.) framed: 90.8 x 58.3 x 7.6 cm (35 3/4 x 22 15/16 x 3 in.) Andrew W. Mellon Collection 1937.1.1 ENTRY The painting shows the Madonna seated frontally on an elaborate, curved, two-tier, wooden throne of circular plan.[1] She is supporting the blessing Christ child on her left arm according to the iconographic tradition of the Hodegetria.[2] Mary is wearing a red mantle over an azure dress. The child is dressed in a salmon-colored tunic and blue mantle; he holds a red scroll in his left hand, supporting it on his lap.[3] In the upper corners of the panel, at the height of the Virgin’s head, two medallions contain busts of two archangels [fig. 1] [fig. 2], with their garments surmounted by loroi and with scepters and spheres in their hands.[4] It was Bernard Berenson (1921) who recognized the common authorship of this work and Enthroned Madonna and Child and who concluded—though admitting he had no specialized knowledge of art of this cultural area—that they were probably works executed in Constantinople around 1200.[5] These conclusions retain their authority and continue to stir debate. -

Reflections on the Religionless Society: the Case of Albania

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 16 Issue 4 Article 1 8-1996 Reflections on the Religionless Society: The Case of Albania Denis R. Janz Loyola University, New Orleans, Louisiana Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation Janz, Denis R. (1996) "Reflections on the Religionless Society: The Case of Albania," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 16 : Iss. 4 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol16/iss4/1 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REFLECTIONS ON THE RELIGIONLESS SOCIETY: THE CASE OF ALBANIA By Denis R. Janz Denis R. Janz is professor of religious studies at Loyola University, New Orleans, · Louisiana. From the time of its inception as a discipline, the scientific study of religion has raised the question of the universality of religion. Are human beings somehow naturally religious? Has there ever been a truly religionless society? Is modernity itself inimical to religion, leading slowly but nevertheless inexorably to its extinction? Or does a fundamental human religiosity survive and mutate into ever new forms, as it adapts itself to the exigencies of the age? There are as of yet no clear answers to these questions. And religiologists continue to search for the irreligious society, or at least for the society in which religion is utterly devoid of any social significance, where the religious sector is a tiny minority made up largely of elderly people and assorted marginal figures. -

BYZANTINE CAMEOS and the AESTHETICS of the ICON By

BYZANTINE CAMEOS AND THE AESTHETICS OF THE ICON by James A. Magruder, III A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland March 2014 © 2014 James A. Magruder, III All rights reserved Abstract Byzantine icons have attracted artists and art historians to what they saw as the flat style of large painted panels. They tend to understand this flatness as a repudiation of the Classical priority to represent Nature and an affirmation of otherworldly spirituality. However, many extant sacred portraits from the Byzantine period were executed in relief in precious materials, such as gemstones, ivory or gold. Byzantine writers describe contemporary icons as lifelike, sometimes even coming to life with divine power. The question is what Byzantine Christians hoped to represent by crafting small icons in precious materials, specifically cameos. The dissertation catalogs and analyzes Byzantine cameos from the end of Iconoclasm (843) until the fall of Constantinople (1453). They have not received comprehensive treatment before, but since they represent saints in iconic poses, they provide a good corpus of icons comparable to icons in other media. Their durability and the difficulty of reworking them also makes them a particularly faithful record of Byzantine priorities regarding the icon as a genre. In addition, the dissertation surveys theological texts that comment on or illustrate stone to understand what role the materiality of Byzantine cameos played in choosing stone relief for icons. Finally, it examines Byzantine epigrams written about or for icons to define the terms that shaped icon production. -

2018 Bibliography

University of Dayton eCommons Marian Bibliographies Research and Resources 2018 2018 Bibliography Sebastien B. Abalodo University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_bibliographies eCommons Citation Abalodo, Sebastien B., "2018 Bibliography" (2018). Marian Bibliographies. 17. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_bibliographies/17 This Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the Research and Resources at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Bibliographies by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Marian Bibliography 2018 Page 1 International Marian Research Institute University of Dayton, Ohio, USA Bibliography 2018 English Anthropology Calloway, Donald H., ed. “The Virgin Mary and Theological Anthropology.” Special issue, Mater Misericordiae: An Annual Journal of Mariology 3. Stockbridge, MA: Marian Fathers of the Immaculate Conception of the B.V.M., 2018. Apparitions Caranci, Paul F. I am the Immaculate Conception: The Story of Bernadette of Lourdes. Pawtucket, RI: Stillwater River Publications, 2018. Clayton, Dorothy M. Fatima Kaleidoscope: A Play. Haymarket, AU-NSW: Little Red Apple Publishing, 2018. Klimek, Daniel Maria. Medjugorje and the Supernatural Science, Mysticism, and Extraordinary Religious Experience. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018. Maunder, Chris. Our Lady of the Nations: Apparitions of Mary in Twentieth-Century Catholic Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018. Musso, Valeria Céspedes. Marian Apparitions in Cultural Contexts: Applying Jungian Concepts to Mass Visions of the Virgin Mary. Research in Analytical Psychology and Jungian Studies. London: Routledge, 2018. Also E-book Sønnesyn, Sigbjørn. Review of William of Malmesbury: The Miracles of the Blessed Virgin Mary. -

Manolis G. Varvounis * – Nikos Rodosthenous Religious

Manolis G. Varvounis – Nikos Rodosthenous Religious Traditions of Mount Athos on Miraculous Icons of Panagia (The Mother of God) At the monasteries and hermitages of Mount Athos, many miraculous icons are kept and exhibited, which are honored accordingly by the monks and are offered for worship to the numerous pilgrims of the holy relics of Mount Athos.1 The pil- grims are informed about the monastic traditions of Mount Athos regarding these icons, their origin, and their miraculous action, during their visit to the monasteries and then they transfer them to the world so that they are disseminated systemati- cally and they can become common knowledge of all believers.2 In this way, the traditions regarding the miraculous icons of Mount Athos become wide-spread and are considered an essential part of religious traditions not only of the Greek people but also for other Orthodox people.3 Introduction Subsequently, we will examine certain aspects of these traditions, based on the literature, notably the recent work on the miraculous icons in the monasteries of Mount Athos, where, except for the archaeological and the historical data of these specific icons, also information on the wonders, their origin and their supernatural action over the centuries is captured.4 These are information that inspired the peo- ple accordingly and are the basis for the formation of respective traditions and re- ligious customs that define the Greek folk religiosity. Many of these traditions relate to the way each icon ended up in the monastery where is kept today. According to the archetypal core of these traditions, the icon was thrown into the sea at the time of iconoclasm from a region of Asia Minor or the Near East, in order to be saved from destruction, and miraculously arrived at the monastery. -

Aspects of St Anna's Cult in Byzantium

ASPECTS OF ST ANNA’S CULT IN BYZANTIUM by EIRINI PANOU A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies Institute of Archaeology and Antiquity College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham January 2011 Acknowledgments It is said that a PhD is a lonely work. However, this thesis, like any other one, would not have become reality without the contribution of a number of individuals and institutions. First of all of my academical mother, Leslie Brubaker, whose constant support, guidance and encouragement accompanied me through all the years of research. Of the National Scholarship Foundation of Greece ( I.K.Y.) with its financial help for the greatest part of my postgraduate studies. Of my father George, my mother Angeliki and my bother Nick for their psychological and financial support, and of my friends in Greece (Lily Athanatou, Maria Sourlatzi, Kanela Oikonomaki, Maria Lemoni) for being by my side in all my years of absence. Special thanks should also be addressed to Mary Cunningham for her comments on an early draft of this thesis and for providing me with unpublished material of her work. I would like also to express my gratitude to Marka Tomic Djuric who allowed me to use unpublished photographic material from her doctoral thesis. Special thanks should also be addressed to Kanela Oikonomaki whose expertise in Medieval Greek smoothened the translation of a number of texts, my brother Nick Panou for polishing my English, and to my colleagues (Polyvios Konis, Frouke Schrijver and Vera Andriopoulou) and my friends in Birmingham (especially Jane Myhre Trejo and Ola Pawlik) for the wonderful time we have had all these years. -

Kreinath, Jens. "Aesthetic Sensations of Mary: the Miraculous Icon Of

Kreinath, Jens. "Aesthetic Sensations of Mary: The Miraculous Icon of Meryem Ana and the Dynamics of Interreligious Relations in Antakya." Figurations and Sensations of the Unseen in Judaism, Christianity and Islam: Contested Desires. By Birgit Meyer and Terje Stordalen. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019. 154–171. Bloomsbury Studies in Material Religion. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 26 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350078666.0017>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 26 September 2021, 12:16 UTC. Copyright © Birgit Meyer, Terje Stordalen and Contributors. This Work is licensed under the Creative Commons License. 2019. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 8 Aesthetic Sensations of Mary: Th e Miraculous Icon of Meryem Ana and the Dynamics of Interreligious Relations in Antakya1 J e n s K r e i n a t h Introduction Antakya – formerly Antioch – is the southernmost city of Turkey, known for its religious and ethnic diversity, with its people belonging to diff erent Christian and Muslim denominations. It is situated with the Mediterranean to the west and borders Syria to the east and south (see Figure 8.1 ). In 1939, Hatay was the last province to offi cially become part of the Republic of Turkey ( Shields 2011 : 17–47, 143–75, 232–49). Now, the ethnically diverse population of about 1.5 million is primarily composed of people of Turkish and Arab descent. With its unique blend of diff erent languages and cultures, Hatay became known for its religious tourism industry. -

Apparitions of the Virgin Mary in Modern European Roman Catholicism

APPARITIONS OF THE VIRGIN MARY IN MODERN EUROPEAN ROMAN CATHOLICISM (FROM 1830) Volume 2: Notes and bibliographical material by Christopher John Maunder Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD The University of Leeds Department of Theology and Religious Studies AUGUST 1991 CONTENTS - VOLUME 2: Notes 375 NB: lengthy notes which give important background data for the thesis may be located as follows: (a) historical background: notes to chapter 1; (b) early histories of the most famous and well-documented shrines (La Salette, Lourdes, Pontmain, Beauraing, Banneux): notes (3/52-55); (c) details of criteria of authenticity used by the commissions of enquiry in successful cases: notes (3/71-82). Bibliography 549 Various articles in newspapers and periodicals 579 Periodicals specifically on the topic 581 Video- and audio-tapes 582 Miscellaneous pieces of source material 583 Interviews 586 Appendices: brief historical and bibliographical details of apparition events 587 -375- Notes NB - Format of bibliographical references. The reference form "Smith [1991; 100]" means page 100 of the book by Smith dated 1991 in the bibliography. However, "Smith [100]" means page 100 of Smith, op.cit., while "[100]" means ibid., page 100. The Roman numerals I, II, etc. refer to volume numbers. Books by three or more co-authors are referred to as "Smith et al" (a full list of authors can be found in the bibliography). (1/1). The first marian apparition is claimed by Zaragoza: AD 40 to St James. A more definite claim is that of Le Puy (AD 420). O'Carroll [1986; 1] notes that Gregory of Nyssa reported a marian apparition to St Gregory the Wonderworker ('Thaumaturgus') in the 3rd century, and Ashton [1988; 188] records the 4th-century marian apparition that is supposed to have led to the building of Santa Maria Maggiore basilica, Rome. -

Rome's Last Efforts Towards the Union of Orthodox Albanians (1929-1946)

Journal of Eastern Christian Studies 58(1-2), 41-83. doi: 10.2143/JECS.58.1.2017736 © 2006 by Journal of Eastern Christian Studies. All rights reserved. ROME’S LAST EFFORTS TOWARDS THE UNION OF ORTHODOX ALBANIANS (1929-1946) INES ANGJELI MURZAKU* INTRODUCTION It would probably be improper to study the history of the Albanian Greek Catholic Church in unity with Rome in isolation from a concurrent move- ment, that is, the struggle to establish an Albanian Autocephalous Church. The two movements have something in common: they were both animated by the desire of the Albanian people for national identity. Indeed, Albania is not an isolated case scenario in ecclesiastical history. Analogous developments have taken place in other Eastern European countries; the case of Bulgaria is the classical example. The move of the Bulgarian Orthodoxy toward Rome was largely inspired by the wish to restore their national identity after cen- turies of coercion, not only by the Turks but also from the Greeks.1 In nine- teenth-century Bulgaria, when the struggle for autocephaly was gaining momentum, several influential Bulgarian Orthodox faithful in Constantino- ple began to contemplate union with Rome as a solution to their national problems. They thought that as Orthodox they would be able to revive their national ecclesiastical traditions, which they thought Constantinople had denied them.2 In fact, the Greeks were profoundly hated in Bulgaria, because * Ines Angjeli Murzaku is Associate Professor of Religious Studies at Seton Hall Univer- sity in South Orange, New Jersey, an Adjunct Associate Professor of Historical Theology at the Graduate School of Theology, Immaculate Conception Seminary, and Lecturer at the Centro per l’Europa Centro-Orientale e Balcanica of the University of Bologna. -

Maestà (Madonna and Child with Four Angels) C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Master of Città di Castello Italian, active c. 1290 - 1320 Maestà (Madonna and Child with Four Angels) c. 1290 tempera on panel painted surface: 230 × 141.5 cm (90 9/16 × 55 11/16 in.) overall: 240 × 150 × 2.4 cm (94 1/2 × 59 1/16 × 15/16 in.) framed: 252.4 x 159.4 x 13.3 cm (99 3/8 x 62 3/4 x 5 1/4 in.) Samuel H. Kress Collection 1961.9.77 ENTRY This panel, of large dimensions, bears the image of the Maestà represented according to the iconographic tradition of the Hodegetria. [1] This type of Madonna and Child was very popular among lay confraternities in central Italy; perhaps it was one of them that commissioned the painting. [2] The image is distinguished among the paintings of its time by the very peculiar construction of the marble throne, which seems to be formed of a semicircular external structure into which a circular seat is inserted. Similar thrones are sometimes found in Sienese paintings between the last decades of the thirteenth and the first two of the fourteenth century. [3] Much the same dating is suggested by the delicate chrysography of the mantles of the Madonna and Child. [4] Recorded for the first time by the Soprintendenza in Siena c. 1930 as “tavola preduccesca,” [5] the work was examined by Richard Offner in 1937. In his expertise, he classified it as “school of Duccio” and compared it with some roughly contemporary panels of the same stylistic circle. -

Mythology and Destiny Albert Doja

Mythology and Destiny Albert Doja To cite this version: Albert Doja. Mythology and Destiny. Anthropos -Freiburg-, Richarz Publikations-service GMBH, 2005, 100 (2), pp.449-462. 10.5771/0257-9774-2005-2-449. halshs-00425170 HAL Id: halshs-00425170 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00425170 Submitted on 1 May 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. H anthropos 100.2005:449-462 1^2 Mythologyand Destiny AlbertDoja Abstract.- In Albaniantradition, the essential attributes of larlyassociated with the person's spirit, with their the mythologicalfigures of destinyseem to be symbolic lifeand death,their health, their future character, interchangeablerepresentations of birth itself. Their mythical theirsuccesses and setbacks. the combatis butthe symbolic representation of the cyclic return Theysymbolize in thewatery and chthonianworld of death,leading, like the person'sproperties, are thespiritual condensation vegetation,tothe cosmic revival of a newbirth. Both protective of theirqualities. They have suchclose mystical anddestructive positions of theattributes of birth,symbolized tieswith the person that merely the way they are by the amnioticmembranes, the caul, and othersingular dealtwith or theaim are ascribeddetermines ofmaternal they markers,or by the means of the symbolism water, theindividual's own and fate. -

Country Advice Albania Albania – ALB36773 – Greece – Orthodox Christian Church – Baptisms – Albania – Church Services – Tirana – Trikala 9 July 2010

Country Advice Albania Albania – ALB36773 – Greece – Orthodox Christian Church – Baptisms – Albania – Church services – Tirana – Trikala 9 July 2010 1. Please search for information on Greece in relation to whether a person cannot be baptised Orthodox if they are illegally in Greece. Information regarding whether a person cannot be baptised Orthodox if they are illegally in Greece was not located in a search of the sources consulted. The Greek constitution establishes the Eastern Orthodox Church of Christ (Greek Orthodox Church) as the prevailing religion in Greece and it was estimated that 97 percent of the population identified itself as Greek Orthodox. The Greek Orthodox Church exercises significant influence and “[m]any citizens assumed that Greek ethnicity was tied to Orthodox Christianity. Some non-Orthodox citizens complained of being treated with suspicion or told that they were not truly Greek when they revealed their religious affiliation.”1 It is reported that most of Greece‟s native born population are baptised into the Orthodox Church.2 A 2004 report indicates that the “Orthodox Church takes on the self anointed role as keeper of the national identity”. The report refers to the comments of a priest in Athens who said that “in Greece, we regard Greeks as the ones who are baptised” and people who were not baptised, immigrants, were not seen as Greek.3 2. Please provide information generally about the Orthodox Church in Albania including, if possible, details about the order of the church service. The Orthodox Autocephalous Church of Albania is one of four traditional religious groups in Albania. The majority of Albanians do not actively practice a faith,4 but it is estimated that 20 to 25 percent of the Albanian population are in communities that are traditionally Albanian Orthodox.