Konzo and Continuing Cyanide Intoxication from Cassava in Mozambique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jentzsch 2018 T

https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl License: Article 25fa pilot End User Agreement This publication is distributed under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act (Auteurswet) with explicit consent by the author. Dutch law entitles the maker of a short scientific work funded either wholly or partially by Dutch public funds to make that work publicly available for no consideration following a reasonable period of time after the work was first published, provided that clear reference is made to the source of the first publication of the work. This publication is distributed under The Association of Universities in the Netherlands (VSNU) ‘Article 25fa implementation’ pilot project. In this pilot research outputs of researchers employed by Dutch Universities that comply with the legal requirements of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act are distributed online and free of cost or other barriers in institutional repositories. Research outputs are distributed six months after their first online publication in the original published version and with proper attribution to the source of the original publication. You are permitted to download and use the publication for personal purposes. All rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyrights owner(s) of this work. Any use of the publication other than authorised under this licence or copyright law is prohibited. If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. -

Ribáuè/Iapala Nampula Mozambique

Electricidade de Moçambique – EDM Sida Rural Electrification Project Ribáuè/Iapala Nampula Mozambique Study on the impact of rural electrification In the Ribáuè, Namiginha and Iapala áreas Ribáuè district Gunilla Akesson Virgulino Nhate February, 2002 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 1 The Ribáuè-Iapala Rural Electrification Project ............................................................................................. 1 The impact study ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Introductory summary..................................................................................................................................... 3 Problems ........................................................................................................................................... 4 EFFECTS AND IMPACT .................................................................................... 5 The Project .................................................................................................................................................... 5 The transmission line ........................................................................................................................ 5 Groups of electricity consumers ....................................................................................................... 6 Economic activities .......................................................................................................... -

Preparatory Study on Triangular Cooperation Programme For

No. Ministry of Agriculture Republic of Mozambique Preparatory Study on Triangular Cooperation Programme for Agricultural Development of the African Tropical Savannah among Japan, Brazil and Mozambique (ProSAVANA-JBM) Final Report March 2010 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. A FD JR 10-007 No. Ministry of Agriculture Republic of Mozambique Preparatory Study on Triangular Cooperation Programme for Agricultural Development of the African Tropical Savannah among Japan, Brazil and Mozambique (ProSAVANA-JBM) Final Report March 2010 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. F The exchange rate applied in the Study is US$1.00 = MZN30.2 US$1.00 = BRL1.727 (January, 2010) Preparatory Study on ProSAVANA-JBM SUMMARY 1. Background of the Study In tropical savannah areas located at the north part of Mozambique, there are vast agricultural lands with constant rainfall, and it has potential to expand the agricultural production. However, in these areas, most of agricultural technique is traditional and farmers’ unions are weak. Therefore, it is expected to enhance the agricultural productivity by introducing the modern technique and investment and organizing the farmers’ union. Japan has experience in agricultural development for Cerrado over the past 20 years in Brazil. The Cerrado is now world's leading grain belt. The Government of Japan and Brazil planned the agricultural development support in Africa, and considered the technology transfer of agriculture for Cerrado development to tropical savannah areas in Africa. As the first study area, Mozambique is selected for triangular cooperation of agricultural development. Based on this background, Japanese mission, team leader of Kenzo Oshima, vice president of JICA and Brazilian mission, team leader of Marco Farani, chief director visited Mozambique for 19 days from September 16, 2009. -

Vamos Ler! / Let’S Read!

Vamos Ler! / Let’s Read! FY 18 QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT 2 JANUARY – MARCH 2018 Contract Number AID-656-TO-000003 April 2018 This report was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Creative Associates International, Inc. This report was made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of Creative Associates International and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................... 3 SUBMISSION REQUIREMENTS ............................................................................. 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 7 RESUMO EXECUTIVO ............................................................................................. 8 1. PROGRAM OVERVIEW .................................................................................. 9 Program Description ............................................................................................................... 9 2. PROGRESS TO DATE................................................................................... 10 Summary of the Quarter: Progress towards the Program Goal ................................. 10 Overview of Activities by Intermediate Result (IR) ...................................................... -

Gaining Insight Into the Magnitude of and Factors Influencing Child Marriage and Teenage Pregnancy and Their Consequences in Mozambique

Gaining insight into the magnitude of and factors influencing child marriage and teenage pregnancy and their consequences in Mozambique Baseline Report December 2016 by Paulo Pires Assistant Professor Faculty of Health Sciences Lurio University Nampula Mozambique & Pam Baatsen Senior Researcher KIT Royal Tropical Institute Amsterdam The Netherlands Preface YES I DO. is a strategic alliance of five Dutch organizations which main aim is to enhance the decision making space of young women about if, when and whom to marry as well as if, when and with whom to have children. Funded by the sexual and reproductive health and rights policy framework of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands, the alliance is a partnership between Plan Nederland, Rutgers, Amref Flying Doctors, Choice for Youth and Sexuality, and the Royal Tropical Institute. Led by Plan NL, the alliance members have committed to a five year programme to be implemented between 2016 and 2020 in seven countries: Ethiopia, Indonesia, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Pakistan and Zambia. The Yes I Do Alliance partners and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands acknowledge that child marriage, teenage pregnancy and female genital mutilation/cutting are interrelated issues that involve high health risks and human rights violations of young women and impede socioeconomic development. Therefore, the Yes I Do programme applies a mix of intervention strategies adapted to the specific context of the target countries. The theory of change consists of five main pathways: 1) behavioural change of community and ‘’gatekeepers’’, 2) meaningful engagement of young people in claiming for their sexual and reproductive health and rights, 3) informed actions of young people on their sexual health, 4) alternatives to the practice of child marriage, female genital mutilation/cutting and teenage pregnancy through education and economic empowerment, and 5) responsibility and political will of policy makers and duty bearers to develop and implement laws towards the eradication of these practices. -

Aprender a Ler (Apal) Contract No

USAID | Aprender a Ler (ApaL) Contract No. AID-656-C-12-00001 FY 2015 3rd Quarterly Progress Report: Apr-Jun 2015 Submitted by World Education, Inc. July 30th, 2015 Contract No. AID-656-C-12-00001 FY 2015 Q3 Progress Report This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International DevelopmentPage | .1 Acronyms & Key Terms ApaL USAID | Aprender a Ler (Learn to Read) APAL/IE USAID | Aprender a Ler Impact Evaluator AWP Annual Work Plan CLIN Contract Line Item Number COP Chief of Party DIPLAC Direcção de Planificação e Cooperação (Directorate for Planning and Cooperation) DNEP Direcção Nacional de Enseno Primario (National Directorate of Primary Education) DNFP Direcção Nacional de Formação de Professores (National Directorate for Teacher Training) DNQ Direcção Nacional de Qualidade (National Directorate for Quality) DPEC Direcção Provincial de Educação e Cultura (Provincial Directorate of Education and Culture) FY Fiscal Year ICP Institutional Capacity Plan (also Plano de Capacitação Institutional or PCI) IEG Impact Evaluation Group IFP Instituto de Formação de Professores (Teacher Training Institute) IGA Institutional Gap Analysis INDE Instituto Nacional de Desenvolvimento de Educação (Curriculum Development Institute) IR Intermediate Result LEI Local education institution LT Lead Trainer (selected Master Teacher or Pedagogical Director) LOC Letter of Commitment (in lieu of MOU agreements at provincial level) MEP Monitoring and Evaluation Plan MINEDH Ministry of Education PCG Provincial Coordination Group PD -

World Bank Document

Sample Procurement Plan (Text in italic font is meant for instruction to staff and should be deleted in the final version of the PP) Public Disclosure Authorized (This is only a sample with the minimum content that is required to be included in the PAD. The detailed procurement plan is still mandatory for disclosure on the Bank’s website in accordance with the guidelines. The initial procurement plan will cover the first 18 months of the project and then updated annually or earlier as necessary). I. General 1. Bank’s approval Date of the procurement Plan [Original: December 2007]: Revision 15 of Updated Procurement Plan, June 2010] 2. Date of General Procurement Notice: Dec 24, 2006 Public Disclosure Authorized 3. Period covered by this procurement plan: The procurement period of project covered from year June 2010 to December 2012 II. Goods and Works and non-consulting services. 1. Prior Review Threshold: Procurement Decisions subject to Prior Review by the Bank as stated in Appendix 1 to the Guidelines for Procurement: [Thresholds for applicable procurement methods (not limited to the list below) will be determined by the Procurement Specialist /Procurement Accredited Staff based on the assessment of the implementing agency’s capacity.] Public Disclosure Authorized Procurement Method Prior Review Comments Threshold US$ 1. ICB and LIB (Goods) Above US$ 500,000 All 2. NCB (Goods) Above US$ 100,000 First contract 3. ICB (Works) Above US$ 15 million All 4. NCB (Works) Above US$ 5 million All 5. (Non-Consultant Services) Below US$ 100,000 First contract [Add other methods if necessary] 2. -

28 August 2002 Systems Network

Famine Early Warning 28 August 2002 Systems Network Highlights • A rapid emergency food needs assessment was conducted from 22 July to 11 August 2002 by teams from WFP, FEWS NET, the Ministry of Agriculture (MADER) and the National Institute of Disaster Management (INGC). Final results of the assessment will be released by the end of August, but preliminary analysis shows a slight increase in the total number of people requiring food aid. • Overall, the number of people needing emergency assistance is expected to drop in Manica, Tete, Inhambane and Gaza, while estimated needs may increase in Sofala and Zambezia with the inclusion of several new districts. • In Nampula Province, the team found no general need for food assistance in the coastal districts despite the effects of cassava disease. Cassava is the main staple food in the region and production has been greatly reduced, but households have other food and income sources (including fishing) that are adequate to meet their minimum food and non-food needs. Urgent action is necessary to multiply and transport disease- resistant varieties to farmers. • Retail maize prices fell slightly in the middle of August in Maputo, due to an increase in supply from various domestic markets. Prices in Beira continued to rise gradually. Prices are higher than normal for this time of year, and they are expected to continue to rise as the year progresses. The rate and extent of the rise will be key determinants of food security in the coming months. • The probability of El Niño has risen to more than 95%, making it virtually certain that El Niño conditions will persist through the remainder of 2002 and into early 2003. -

African Development Bank Group

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP MOZAMBIQUE NATIONAL RURAL WATER SUPPLY AND SANITATION PROGRAM (PRONASAR) IN NAMPULA AND ZAMBEZIA PROVINCES PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT (PCR) Public Disclosure Authorized RDGS/AHWS December 2017 Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT AFRICAN FOR PUBLIC SECTOR OPERATIONS (PCR) DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP I BASIC DATA A Report data Report date Date of report: November 30th 2017 Mission date (if field mission) From: November 26th 2017 To: 30th November 2017 Field district visit was done from 9th to 16th November 2017 B Responsible Bank staff Positions At approval At completion Regional Director Frank BLACK Mrs Josephine NGURE Country Manager Alice HAMER Joseph RIBEIRO Sector Director Ali KIES Osward CHANDA Sector Manager Sering B. JALLOW Noel KULEMEKA Task Manager Boniface ALEOBUA Boniface ALEOBUA Alternate Task Manager - - PCR Team Leader Eskendir A DEMISSIE Mecuria ASSEFAW; Yolanda ARCELINA, PCR Team Members Boniface ALEOBUA and Pedro SIMONE C Program data Program name: National Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Program (PRONASAR) in Nampula and Zambezia Provinces Program code: P-MZ-E00-008 Instrument number(s): ADB 5800155000601 & ADF 2100150023298 Program type: GRANT & LOAN Sector: Water and Sanitation Country: Mozambique Environmental categorization (1-3): 2 Processing milestones – Bank approved Key Events (Bank approved financing Disbursement and closing dates financing only (add/delete rows depending on only) (Bank approved financing only) the number of financing sources) Financing source/ instrument1: -

IMF Man Heads Central Bank, but Nyusi Warns Him to Resist Foreign Pressure

MOZAMBIQUE News reports & clippings 338 5 September 2016 Editor: Joseph Hanlon ( [email protected]) To subscribe: tinyurl.com/sub-moz To unsubscribe: tinyurl.com/unsub-moz Previous newsletters, more detailed press reports in English and Portuguese, and other Mozambique material are posted on bit.ly/mozamb This newsletter can be cited as "Mozambique News Reports & Clippings" __________________________________________________________________________ Comment: something will turn up: http://bit.ly/28SN7QP Oxfam blog: Bill Gates & chickens: http://oxfamblogs.org/fp2p/will-bill-gates-chickens-end-african-poverty/ Chickens and beer: A recipe for agricultural growth in Mozambique by Teresa Smart and Joseph Hanlon is on http://bit.ly/chickens-beer Gas for development or just for money? is on http://bit.ly/MozGasEn Debt & Development book chapter is on http://bit.ly/Debt-Dev __________________________________________________________________________ Also in this issue: Renamo escalates low cost but high profile attacks __________________________________________________________________________ IMF man heads central bank, but Nyusi warns him to resist foreign pressure After nearly 30 years at the IMF and 39 years outside the country, Rogério Zandamela has returned to Mozambique to head Banco de Moçambique (BdM). His surprise appointment was only announced on Wednesday 31 August and he was sworn in on Thursday. His main task will be to reach agreement with the IMF on how to deal with the $2.2 billion in secret debt, but he also faces rising inflation and rapid devaluation. After the swearing in, Zandamela said “we must restore trust in the Mozambican economy” and warned that there are “enormous sacrifices” ahead. Born in Inhambane, Zandamela attended secondary school in the colonial era at Liceu António Enes (now Escola Francisco Manyanga in Maputo) and in 1975 began to study economics at Universidade de Lourenço Marques (now Universidade Eduardo Mondlane) with a group of students that included the current Prime Minister Carlos Agostinho do Rosário. -

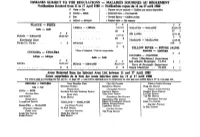

MALADIES SOUMISES AU RÈGLEMENT Notifications Received from 11 to 17 April 1980 — Notifications Reçues Dn 11 Au 17 Avril 1980 C Cases — C As

Wkly Epidem. Rec * No. 16 - 18 April 1980 — 118 — Relevé èpidém, hebd. * N° 16 - 18 avril 1980 investigate neonates who had normal eyes. At the last meeting in lement des yeux. La séné de cas étudiés a donc été triée sur le volet December 1979, it was decided that, as the investigation and follow et aucun effort n’a été fait, dans un stade initial, pour examiner les up system has worked well during 1979, a preliminary incidence nouveau-nés dont les yeux ne présentaient aucune anomalie. A la figure of the Eastern District of Glasgow might be released as soon dernière réunion, au mois de décembre 1979, il a été décidé que le as all 1979 cases had been examined, with a view to helping others système d’enquête et de visites de contrôle ultérieures ayant bien to see the problem in perspective, it was, of course, realized that fonctionné durant l’année 1979, il serait peut-être possible de the Eastern District of Glasgow might not be representative of the communiquer un chiffre préliminaire sur l’incidence de la maladie city, or the country as a whole and that further continuing work dans le quartier est de Glasgow dès que tous les cas notifiés en 1979 might be necessary to establish a long-term and overall incidence auraient été examinés, ce qui aiderait à bien situer le problème. On figure. avait bien entendu conscience que le quartier est de Glasgow n ’est peut-être pas représentatif de la ville, ou de l’ensemble du pays et qu’il pourrait être nécessaire de poursuivre les travaux pour établir le chiffre global et à long terme de l’incidence de ces infections. -

IBIS in Mozambique Country Strategy 2013-17

IBIS in Mozambique Country Strategy 2013-17 20 November 2012 PDF 58 pages IBIS in Mozambique Country Strategy 2013-2017 2 IBIS in Mozambique Country Strategy 2013-2017 Acronyms AC Agents for Change ADE Apoio Directo à Escola AI Access to Information AM Assembleia Municipal ANCEFA Africa Network Campaign on Education For All CBO Community Based Organization CC Conselho Consultivo CE Conselhos da Escola CEDER Centro de Desenvolvimento de Recursos CEDESC Centro de Desenvolvimento da Sociedade Civil CIMU Cidadão e Mudança CIP Centro de Integridade Pública CNJ Conselho Nacional da Juventude CO Country Office COCIM Constructing Citizenship in Mozambique CS Country Strategy CSO Civil Society Organization CSR Corporate Social Responsibility DKK Danish Crown DP Development Partners EFA Education for All EITI Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative EPAC Educação Participativa para a Comunidade FASE Fundo de Apoio ao Sector de Educação FDD Fundo de Desenvolvimento Distrital FDI Foreign Direct Investment FM Fórum Mulher FO Field Office FOCAD Fórum das Associações de Cabo Delgado FOFEN Fórum das Organizações Femininas de Niassa FONGZA Fórum das Organizações Não Governamentais da Zambézia FORASC Fórum das Associações da Sociedade Civil de Cuamba GBS General Budget Support GCE General Certificate of Education GDP Gross National Product HDI Human Development Index HO Head Office ICT Information and Communication Technology IESE Instituto de Estudos Sociais e Económicos IFP Instituto de Formação de Professores INE Instituto Nacional de Estatística