Rainer Werner Fassbinder Edited By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

Index Academy Awards (Oscars), 34, 57, Antares , 2 1 8 98, 103, 167, 184 Antonioni, Michelangelo, 80–90, Actors ’ Studio, 5 7 92–93, 118, 159, 170, 188, 193, Adaptation, 1, 3, 23–24, 69–70, 243, 255 98–100, 111, 121, 125, 145, 169, Ariel , 158–160 171, 178–179, 182, 184, 197–199, Aristotle, 2 4 , 80 201–204, 206, 273 Armstrong, Gillian, 121, 124, 129 A denauer, Konrad, 1 3 4 , 137 Armstrong, Louis, 180 A lbee, Edward, 113 L ’ Atalante, 63 Alexandra, 176 Atget, Eugène, 64 Aliyev, Arif, 175 Auteurism , 6 7 , 118, 142, 145, 147, All About Anna , 2 18 149, 175, 187, 195, 269 All My Sons , 52 Avant-gardism, 82 Amidei, Sergio, 36 L ’ A vventura ( The Adventure), 80–90, Anatomy of Hell, 2 18 243, 255, 270, 272, 274 And Life Goes On . , 186, 238 Anderson, Lindsay, 58 Baba, Masuru, 145 Andersson,COPYRIGHTED Karl, 27 Bach, MATERIAL Johann Sebastian, 92 Anne Pedersdotter , 2 3 , 25 Bagheri, Abdolhossein, 195 Ansah, Kwaw, 157 Baise-moi, 2 18 Film Analysis: A Casebook, First Edition. Bert Cardullo. © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 284 Index Bal Poussière , 157 Bodrov, Sergei Jr., 184 Balabanov, Aleksei, 176, 184 Bolshevism, 5 The Ballad of Narayama , 147, Boogie , 234 149–150 Braine, John, 69–70 Ballad of a Soldier , 174, 183–184 Bram Stoker ’ s Dracula , 1 Bancroft, Anne, 114 Brando, Marlon, 5 4 , 56–57, 59 Banks, Russell, 197–198, 201–204, Brandt, Willy, 137 206 BRD Trilogy (Fassbinder), see FRG Barbarosa, 129 Trilogy Barker, Philip, 207 Breaker Morant, 120, 129 Barrett, Ray, 128 Breathless , 60, 62, 67 Battle -

70 Neue Filme Von ROSA VON PRAUNHEIM 70 Rosa Von Praunheim in DER FRÖHLICHE SERIENMÖRDER ROSAS WELT: 70 FILME

BASIS-FILM VERLEIH präsentiert ROSAS WELT 70 neue Filme von ROSA VON PRAUNHEIM 70 Rosa von Praunheim in DER FRÖHLICHE SERIENMÖRDER ROSAS WELT: 70 FILME Rosa von Praunheim präsentiert zu seinem 70. Ge- und im Fernsehen. Die lustvollen Erkundungen Rosa burtstag 70 neue Filme. Eine Gemeinschaftspro- von Praunheims geben Einblicke in das Leben unter- duktion mit dem Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg, schiedlichster Menschen in Berlin und Brandenburg, der Bundesrepublik, Polen, Lettland, Rumänien, Russ- in Zusammenarbeit mit arte, gefördert vom Me- land, der Schweiz, den USA und China. Praunheim, ein dienboard Berlin-Brandenburg und der Film- und Meister des Interviews, öffnet sie – ermöglicht dem Medienstiftung NRW. Zuschauer intensive Begegnungen mit Menschen, die “ganz normal” sind und “ganz anders”. Rosa von Praunheim ist eine Ikone in der Szene: Ein Praunheims eindringliche, sensible und geistreiche Wegbereiter, ein schwuler Aktivist. Und ein ganz be- filmische Handschrift versprechen subjektive, authen- sonderer Filmemacher aus Berlin. Ein großartiger Er- tische deutsche und internationale Lebens- und Sitten- zähler, ein liebevoller Provokateur. bilder. Am 25. November 2012 feiert der Grimme-Preisträger Die mediale Beachtung ist diesem charmant größen- seinen 70. Geburtstag. wahnsinnigen Unterfangen gewiss. Nach 70 Filmen, die der große deutsche Filmemacher bisher vorgelegt hat, arbeitet Rosa von Praunheim an Die einzelnen Filme lassen ein facettenreiches Kalei- einem einzigartigen Projekt: Zusammen mit Arte und doskop aus Porträts, Lebens- und Sittenbildern entste- dem Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg wird er zu seinem hen. Neben dem Film über den Berliner Preußenpark 70sten 70 neue Filme vorlegen! Das ehrgeizige Projekt wird das Porträt einer Brandenburger Familie stehen. hat Potential für ein filmisches Event. Auf der Leinwand Etliche Filme haben eine große Leichtigkeit, einige sind sehr intensiv und anspruchsvoll (und eher für die späte eine Ausstellung zu Rosas Filmen unter dem Titel Ro- Stunde). -

WER IST HELENE SCHWARZ? Berlinale Special WHO IS HELENE SCHWARZ? QUI EST HELENE SCHWARZ? Regie: Rosa Von Praunheim

IFB 2005 WER IST HELENE SCHWARZ? Berlinale Special WHO IS HELENE SCHWARZ? QUI EST HELENE SCHWARZ? Regie: Rosa von Praunheim Deutschland 2004 Dokumentarfilm mit Helene Schwarz Länge 85 Min. Reinhard Hauff Format Digi Beta Michael Ballhaus Farbe Gerd Conradt Thomas Giefer Stabliste Peter Lilienthal Buch Rosa von Praunheim Helke Sander Kamera Lorenz Haarmann Harun Farocki Schnitt Mike Shephard Claudia Karohs Online-Schnitt Oskar Kammerer Hans-Otto Krüger Ton Lilly Grote Hans Helmut Prinzler Produzent Rosa von Praunheim Wolfgang Becker Redaktion Martin Pieper Helga Reidemeister Co-Produktion ZDF/Arte, Mainz Manfred Stelzer Lilly Grote Produktion Thomas Schadt Rosa von Praunheim Film Wilma Pradetto Konstanzer Str. 56 Detlev Buck D-10707 Berlin Drago Hari Tel.: 030-883 54 96 Volker Schlöndorff Fax: 030-881 29 58 Christian Petzold [email protected] Tom Tykwer Chris Kraus Weltvertrieb noch offen Helene Schwarz WER IST HELENE SCHWARZ? Wer ist Helene Schwarz? Nur Eingeweihte kennen sie, die am 13. Februar 1966 als Sekretärin an der Deutschen Film- und Fernsehakademie (DFFB) in Berlin begann und heute, mit 78 Jahren, immer noch als Studienberaterin und Muse tätig ist. Berühmte Namen pflastern ihren Weg – darunter der Hollywood-Regisseur Wolfgang Petersen, das spätere RAF-Mitglied Holger Meins sowie die Regis- seure Wolfgang Becker, Detlev Buck und Christian Petzold, die sich gern daran erinnern, wie sie im Büro von Helene alle Sorgen vergaßen, wenn sie dort Kaffee tranken und ihr Herz ausschütten durften. Helene wurde Freun- din und Beraterin von inzwischen unzähligen Filmstudenten. Das Besondere an Helene ist ihre Herzlichkeit, die wirklich jeden, der ihr be- gegnet, in ihren Bann zieht – auch mich, der ich Ende der 1960er Jahre ge- meinsam mit Werner Schroeter und Rainer Werner Fassbinder an der Aka- demie abgelehnt wurde, aber Helene treu geblieben bin. -

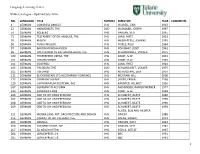

1 Language Learning Center Video Catalogue

Language Learning Center Video Catalogue – Updated July 2016 NO. LANGUAGE TITLE FORMAT DIRECTOR YEAR COMMENTS 4 GERMAN CONGRESS DANCES VHS CHARELL, ERIK 1932 22 GERMAN HARMONISTS, THE DVD VILSMAIER, JOSEPH 1997 54 GERMAN KOLBERG VHS HARLAN, VEIT 1945 71 GERMAN TESTAMENT OF DR. MABUSE, THE VHS LANG, FRITZ 1933 95 GERMAN MALOU VHS MEERAPFELE, JEANINE 1983 96 GERMAN TONIO KROGER VHS THIELE, ROLF 1964 97 GERMAN BARON MUNCHHAUSEN VHS VON BAKY, JOSEF 1943 99 GERMAN LOST HONOR OF KATHARINA BLUM, THE VHS SCHLONDORFF, VOLKER 1975 100 GERMAN THREEPENNY OPERA, THE VHS PABST, G.W. 1931 101 GERMAN JOYLESS STREET VHS PABST, G.W. 1925 102 GERMAN SIEGFRIED VHS LANG, FRITZ 1924 103 GERMAN TIN DRUM, THE DVD SCHLONDORFF, VOLKER 1975 105 GERMAN TIEFLAND VHS RIEFENSTAHL, LENI 1954 111 GERMAN BLICKKONTAKE (TO ACCOMPANY KONTAKE) VHS MCGRAW HILL 2000 127 GERMAN GERMANY AWAKE VHS LEISER, ERWIN 1968 129 GERMAN CAPTAIN FROM KOEPENIK, THE VHS KAUNTER, HELMUT 1956 167 GERMAN GERMANY IN AUTUMN VHS FASSBINDER, RANIER WERNER 1977 199 GERMAN PANDORA'S BOX VHS PABST, G.W. 1928 206 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 207 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 208 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 209 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 ROSEN, BOB AND ANDREA 211 GERMAN VIENNA 1900: ART, ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN VHS SIMON 1986 253 GERMAN CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI, THE VHS WIENE, ROBERT 1919 265 GERMAN DAMALS VHS HANSEN, ROLF 1943 266 GERMAN GOLDENE STADT, DIE VHS HARLAN, VEIT 1942 267 GERMAN ZU NEUEN -

Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination EDITED BY TARA FORREST Amsterdam University Press Alexander Kluge Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination Edited by Tara Forrest Front cover illustration: Alexander Kluge. Photo: Regina Schmeken Back cover illustration: Artists under the Big Top: Perplexed () Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn (paperback) isbn (hardcover) e-isbn nur © T. Forrest / Amsterdam University Press, All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustra- tions reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. For Alexander Kluge …and in memory of Miriam Hansen Table of Contents Introduction Editor’s Introduction Tara Forrest The Stubborn Persistence of Alexander Kluge Thomas Elsaesser Film, Politics and the Public Sphere On Film and the Public Sphere Alexander Kluge Cooperative Auteur Cinema and Oppositional Public Sphere: Alexander Kluge’s Contribution to G I A Miriam Hansen ‘What is Different is Good’: Women and Femininity in the Films of Alexander Kluge Heide -

Filmszem Iii./2

FASSBINDER III. Évf. 2. szám Nyár FILMSZEM III./2. Rainer Werner Fassbinder FILMSZEM - filmelméleti és filmtörténeti online folyóirat III. évfolyam 2. szám - NYÁR (Online: 2013. JÚNIUS 30.) Főszerkesztő: Farkas György Szerkesztőbizottság tagjai: Murai Gábor, Kornis Anna Felelős kiadó: Farkas György Szerkesztőség elérhetősége: [email protected] ISSN 2062-9745 Tartalomjegyzék Bevezető 4 Bács Ildikó: A néma szereplő, avagy úr és szolga viszonya 5-14 Turnacker Katalin: A tükörjáték struktúrája - Berlin Alexanderplatz 15-32 Farkas György: Párhuzamos világok utazói - R. W. Fassbinder és Masumura Yasuzō filmjeinek összehasonlító vizsgálata 33-45 Rainer Werner Fassbinder filmográfia - összeállította Farkas György 46-91 Bevezető Bevezető Bár R. W. Fassbinder már több mint 30 éve elhunyt, a német új film és egyben az egyetemes filmművészet e kivételesen termékeny és különleges alkotójá- ról magyarul meglehetősen kevés elméleti munka látott napvilágot. Életmű- vének sokszínűségét még számos területen és számos megközelítési módon lehetne és kellene tárgyalni. Mostani lapszámunk ezt a hiányt igyekszik némileg csökkenteni azzal, hogy Fassbinder munkásságáról, hatásáról, filmtörténeti helyéről szóló értel- mező anyagokat válogattunk össze. Bács Ildikó tanulmányában a néma szereplő felhasználásának szempontjait elemzi összehasonlítva Fassbinder Petra von Kant keserű könnyei című filmjét Beckett Godot-ra várva című drámájával. Turnacker Katalin a fassbinder-i életmű egy nagyon hangsúlyos darabját, az Alfred Döblin regényéből, a Berlin, Alexanderplatz-ból készült tv-sorozatot elemzi, mint a tükörjáték struktúrája. Sajátos megközelítést mutat be Farkas György írása, amelyben Fassbinder há- rom kiválasztott filmjét állítja párhuzamba egy japán filmrendező, Masumura Yasuzō három alkotásával, kiemelve azokat az alapvető közös gondolatokat, amik nem csak a két rendező között teremtenek kapcsolatot, de alátámaszt- ják mindkettejük zsenialitását is. -

Course Outline

Prof. Fatima Naqvi German 01:470:360:01; cross-listed with 01:175:377:01 (Core approval only for 470:360:01!) Fall 2018 Tu 2nd + 3rd Period (9:50-12:30), Scott Hall 114 [email protected] Office hour: Tu 1:10-2:30, New Academic Building or by appointment, Rm. 4130 (4th Floor) Classics of German Cinema: From Haunted Screen to Hyperreality Description: This course introduces students to canonical films of the Weimar, Nazi, post-war and post-wall period. In exploring issues of class, gender, nation, and conflict by means of close analysis, the course seeks to sensitize students to the cultural context of these films and the changing socio-political and historical climates in which they arose. Special attention will be paid to the issue of film style. We will also reflect on what constitutes the “canon” when discussing films, especially those of recent vintage. Directors include Robert Wiene, F.W. Murnau, Fritz Lang, Lotte Reiniger, Leni Riefenstahl, Alexander Kluge, Volker Schlöndorff, Werner Herzog, Wim Wenders, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Andreas Dresen, Christian Petzold, Jessica Hausner, Michael Haneke, Angela Schanelec, Barbara Albert. The films are available at the Douglass Media Center for viewing. Taught in English. Required Texts: Anton Kaes, M ISBN-13: 978-0851703701 Recommended Texts (on reserve at Alexander Library): Timothy Corrigan, A Short Guide to Writing about Film Rob Burns (ed.), German Cultural Studies Lotte Eisner, The Haunted Screen Sigmund Freud, Writings on Art and Literature Siegfried Kracauer, From Caligari to Hitler Anton Kaes, Shell Shock Cinema: Weimar Cinema and the Wounds of War Noah Isenberg, Weimar Cinema Gerd Gemünden, Continental Strangers Gerd Gemünden, A Foreign Affair: Billy Wilder’s American Films Sabine Hake, German National Cinema Béla Balász, Early Film Theory Siegfried Kracauer, The Mass Ornament Brad Prager, The Cinema of Werner Herzog Eric Ames, Ferocious Reality: Documentary according to Werner Herzog Eric Ames, Werner Herzog: Interviews N. -

Kurt Hübner- Der Intendant

Kurt Hübner- Der Intendant Seine Stationen: Ulm- 1959-1962 Bremen- 1962-1973 Berlin- 1973-1986 1 ANHANG 1959-1986: DIE AUFFÜHRUNGEN DER INTENDANTENZEIT KURT HUBNERS I. ULM 1959-1962 Das Ensemble Schauspiel (Herren) Schauspiel (Damen) Oper I Operette Oper I Operette Peter Böhlke Elisabeth Botz (Herren) (Damen) Kar! Heinz Bürkel Käthe Druba Lambertus Bijnen Lisa Anders Will Court Angela Gotthardt Kari-Heinz von Eicken Helen Borbjerg Josef Gessler Friede! Heizmann Helmuth Erfurth Anita Butler Joachim Giese Hannelore Hoger George Fortune RuthConway Günter Hanke Alke Hoßfeld Jan Gabrielis Irmgard Dressler Hans-H. Hassenstein Elisabeth Karg Josef Gessler Josette Genet-Bollinger Valentin Jeker Maria-Christina Müller Peter Haage Marjorie Hall Rolf Johanning Elisabeth Orth Kar! Hauer Rita Hermann Norbert Kappen Helga Riede! J osef Kayrooz Marian Krajewska Jon Laxdall Ursula Siebert Bernd Küpper Liane Lehrer Georg von Manikowski Katharina Tüschen Bill Lucas Christine Mainka Dieter Möbius Erika Wackernagel Fritz Neugebauer Gertrud Probst Siegfried Munz Sabine Werner Richard Owens Gertrud Romvary Walther Fr. Peters Fritz Peter Ursula Schade Rudolf Peschke Heinrich Reckler Ingeborg Steiner Hans Jakob Poiesz Herbert Reiter Patricia Hyde Thomas Friedhelm Ftok Heinz Röthig Eva-Maria Wolff Willi Ress Hermann Runge Hermann Schlögl Fred Straub Hermann Schober Walter Voges Alois Strempel Heinz Weigand Peter Striebeck Kar! Schurr Rainald Walter RolfWiest 2 SPIELZEIT 1959/60 das zu überwinden, was gegen die Figur des Posa, die naive Leichtgläubigkeit des Carlos Carl Maria von Weber: und gegen andere alogische Entwicklungen Der Freischütz (29. 8. 59) gesagt werden kann. Schillers Feuerodem, ML: Harald von Goertz; 1: JosefWitt; hier zum erstenmal in reine, gehämmerte B: Hansheinrich Palitzsch Verse gebändigt, überall diese Bedenklich keiten siegen zu Jassen, fast möchte man Friedrich Schiller: Don Carlos (3. -

Rainer Werner Fassbinder QUERELLE 1985

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Wilhelm Solms Rainer Werner Fassbinder QUERELLE 1985 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/2460 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Solms, Wilhelm: Rainer Werner Fassbinder QUERELLE. In: Augen-Blick. Marburger Hefte zur Medienwissenschaft. Heft 1-2: Der neueste deutsche Film. Zum Autorenfilm (1985), S. 22–29. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/2460. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under a Deposit License (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, non-transferable, individual, and limited right for using this persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses document. This document is solely intended for your personal, Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für non-commercial use. All copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute, or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the conditions of vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder use stated above. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. -

NEW Dvds ADDED to the COLLECTION APRIL 16, 2004 – AUGUST 31, 2004

NEW DVDs ADDED TO THE COLLECTION APRIL 16, 2004 – AUGUST 31, 2004. All quiet on the western front /a Universal-International presentation ; produced by Carl Laemmle, Jr. ; directed by Lewis Milestone. AVRDVD0113 The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman / produced by Philip Barry Jr., Robert W. Christiansen and Rick Rosenberg ; screenplay by Tracy Keenan Wynn ; directed by John Korty. AVRDVD0838 Basic math / written by the Standard Deviants academic team, including Richard Semmler and Roger Howey. AVRDVD0899 Brooklyn Bridge /a film by Ken Burns ; produced by Florentine Films in association with the Department of Records and Information Services of the City of New York and WNET/THIRTEEN ; PBS ; directed by Ken Burns ; written by Amy Stechler. AVRDVD0825 Chemistry of cooking / Classroom Video ; executive producer, John Davis. AVRDVD1121 Causes of World War I /Classroom Video presents ; written and produced by Brenden Dannaher ; exeuctive producer, John Davis. AVRDVD0902 Establishing a small business : case study of a cafe / Classroom Video. AVRDVD0901 Cooking utensils / produced by Classroom Video. AVRDVD1122 Going vegetarian / by Classroom Video. AVRDVD1123 A day in the life of a cafe owner / produced by Classroom Video. AVRDVD1124 A day in the life of a stay-at-home dad / produced by Classroom Video. AVRDVD1125 Oil refining : fractional distillation, sulfur, cracking / produced by Classroom Video. AVRDVD1126 Redox rocks / produced by Classroom Video. AVRDVD1127 Sergeant Magnet of the electron army : how electricity works at the atomic level / produced by Classroom Video. AVRDVD1128 Holding electrons / produced by Classroom Video. AVRDVD1129 History of the atom. Part two, Key experiments that established atomic structure / produced by Classroom Video. AVRDVD1130 Martin Scorsese presents the blues : a musical journey / Vulcan Productions and Road Movies Production in association with Cappa Productions & Jigsaw Productions. -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 -

“Rainer Werner Fassbinder: a Retrospective”

PRESS RELEASE WHAT: Werner Fassbinder Retrospective WHEN: March 10 to April 22, 2018 WHERE: Ili Likha Artists Village in Baguio and Cinematheque Centre Manila “Rainer Werner Fassbinder: A Retrospective” IN PARTNERSHIP WITH: This summer, the Goethe-Institut Philippinen presents some of the best works of the well-acclaimed German filmmaker, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, in a retrospective exhibition that's free for all. Eleven Fassbinder films including a documentary about him will be screened for free every weekends from March 10 to April 1 at the Ili Likha Artists Village in Baguio and April 7 to April 22 at the Cinematheque Centre Manila. On the opening day at Ili Likha Artists Village this March 10, a small reception will be held at 4pm before the first screening. Rainer Werner Fassbinder (1945–82) is one of the most polarizing and influential figures of the New German Cinema. He is famously known for his short-lived yet exceptional and remarkable career that lasted for nearly 16 years until his death in 1982. Fassbinder's artistic productivity resulted in a legacy of 39 films, 6 TV movies, 3 shorts, 4 video productions, 24 stage plays, and 4 radio plays. On top of that, he was also an actor, dramatist, cameraman, composer, designer, editor, producer, and theatre manager for some of his films and productions, yet he managed to combine all of it into a comprehensive, always expanding, retrospective, and progressive unity. Fassbinder's films encompasses everything from intense social melodramas, Hollywood inspired female-driven tearjerkers, epic period pieces, to dystopic science fiction as well.