The Intersectionality of Ethics, Culture And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Life

STUDENT LIFE HOMECOMING Homecoming is a unique tradition at the University of Rhode Island celebrated by students and alumni of all ages. On a large field people, cars, trucks, and moving vans stretch for miles. Music blares in all directions. The smell of the barbecue and the sound of beer cans cracking open fills the air. There is laughter, singing, dancing, and fun. Both students and alumni anticipate this October day for months. At the same are time there shouts in the background as friends and family cheer on the Rhody Rams as they the rival challenge Maine Bears. The game begins with the recognition of past football players and marching band members. Half-time continues this support of URI students and alumni by honoring the Homecoming King and Queen, Jeremiah Stone and Melanie Mecca. These two individuals are crowned for their outstanding campus and community involvement and their upstanding personalities. Whether celebrating at the football stadium or in the field behind it. Homecoming is a memorable event for all. Sorority sisters and fraternity brothers reunite. Old friends rebuild bonds with those they have not seen in years. Recent graduates come back with their "real world" stories and relive their college experiences. Older alumni witness the remarkable changes that have occurred at the University. Homecoming reminds us all of the days long gone, but not forgotten. It keeps the memories and experiences of the University of Rhode Island alive, in triendb and family. What is being trashed, posessions stolen, and a wad "down-the-line? of money in your pocket which was Down the line has many different generated from the collection at the door. -

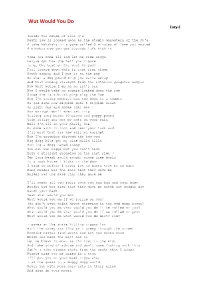

Eazy-E Wut Would You Do

Wut Would You Do Eazy-E Inside the minds of real g's Death row is looked upon as the studio gangsters of the 90's A joke hahahaha in a game called 5 minutes of fame you wasted 4 minutes now you got seconds left kick it Come one come all and let me ride nigga Eazy-e cpt how the hell you figure To be the best on the west hu you? Fool locked down this is east side nigga South comton and I put it on the map So when a dog pound crip you wanna scrap And that coming straight from the ruthless gangster Eazy-e Now what would I do ha ha let's see Now I would take on sugars locked down the row Since Dre is a bitch pimp slap the hoe Now I'm seeing doubles man two dogs in a huddle Aa god dame now diggidi daze I biggidi blast On right one and smoke that ass Now corrupt don't even set trip Yelling long beach 60 blood and puppy pound Crip really doe got my nuts on your chin Well I'm all in your philly hoe So come with it fool and test your luck and I'll beat that ass now call me corrupt Now I'm creeping through the fog you Big dogg blue got my nine milla killa Hunting a dogg named snoop You can run nigga but you can't hide Eazy-e straight creeping on the east side 7 Ten-long beach south caught snoop free basin In a rock house I kicks in the door I said it before I never let no busta test me no more Bang murder was the case that they gave me Murder was the case that they gave me I'll smoke all you fools even you boo boo and your baby Murder was the case that they gave me watch out buddie boy Watch your back Yeah what would you do? What would you do if -

Snoop Dogg Wet (G-Mix) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Snoop Dogg Wet (G-Mix) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Wet (G-Mix) Country: Japan Released: 2010 MP3 version RAR size: 1785 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1621 mb WMA version RAR size: 1951 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 922 Other Formats: AU MP2 FLAC RA AC3 APE DTS Tracklist Hide Credits Wet (G-Mix) A1 Featuring – Jim Jones , Shawty Lo A2 Wet (Main) A3 Wet (Instrumental) Don't Need No Bitch B1 Featuring – Brian Honeycutt, Devin The Dude B2 That Good Platinum B3 Featuring – R. Kelly Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Snoop Dogg Vs Snoop David Guetta - Dogg Vs Capitol none Sweat (David Guetta none US 2011 David Records Remix) (File, AAC, Guetta Single, 256) Snoop Dogg Vs Snoop David Guetta - Dogg Vs none Sweat (David Guetta Parlophone none UK 2011 David Remix) (CDr, Single, Guetta Promo) Sweat (David Guetta Snoop & Afrojack Dub Priority 5099908322159 5099908322159 US 2011 Dogg Remix) (File, MP3, Records Single, 320) Snoop Snoop Dogg vs Dogg vs David Guetta - none EMI none Sweden 2011 David Sweat / Wet (CDr, Guetta Maxi, Promo) Snoop Snoop Dogg vs Doggy Style 509990 28536 2 Dogg vs David Guetta - Records , 509990 28536 2 Germany 2011 8 David Sweat (Remix) (CD, Priority 8 Guetta Single) Records Related Music albums to Wet (G-Mix) by Snoop Dogg Snoop Dogg - Sensual Seduction Snoop Dogg feat. Charlie Wilson - Peaches N Cream Snoop Dogg - Boom Snoop Dogg - Snoop Dogg / Backup Ho Snoop Dogg - Snoop Dogg Snoop Dogg - Smokefest 2 Snoop Dogg - Wet (Remixes) Snoop Dogg - Late Nights Suge Knight, Dr. -

Underground Rap Albums 90S Downloads Underground Rap Albums 90S Downloads

underground rap albums 90s downloads Underground rap albums 90s downloads. 24/7Mixtapes was founded by knowledgeable business professionals with the main goal of providing a simple yet powerful website for mixtape enthusiasts from all over the world. Email: [email protected] Latest Mixtapes. Featured Mixtapes. What You Get With Us. Fast and reliable access to our services via our high end servers. Unlimited mixtape downloads/streaming in our members area. Safe and secure payment methods. © 2021 24/7 Mixtapes, Inc. All rights reserved. Mixtape content is provided for promotional use and not for sale. The Top 100 Hip-Hop Albums of the ’90s: 1990-1994. As recently documented by NPR, 1993 proved to be an important — nay, essential — year for hip-hop. It was the year that saw 2Pac become an icon, Biz Markie entangled in a precedent-setting sample lawsuit, and the rise of the Wu-Tang Clan. Indeed, there are few other years in hip- hop history that have borne witness to so many important releases or events, save for 1983, in which rap powerhouse Def Jam was founded in Russell Simmons’ dorm room, or 1988, which saw the release of about a dozen or so game-changing releases. So this got us thinking: Is there really a best year for hip-hop? As Treble’s writers debated and deliberated, we came up with a few different answers, mostly in the forms of blocks of four or five years each. But there was one thing they all had in common: they were all in the 1990s. Now, some of this can be chalked up to age — most of Treble’s staff and contributors were born in the 1980s, and cut their musical teeth in the 1990s. -

Michel'le Album Download Michel'le Album Download

michel'le album download Michel'le album download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67b1102178184ebc • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Michel'le. Michel'le, the girl with the squeaky speaking voice and thunderous singing voice, stormed onto the music scene in 1989-1990 with her smash self- titled debut. The album is post-new jill swing, incorporating a mix of hip-hop, dance, and R&B well before Mary J. Blige and Faith Evans perfected the genre. Michel'le produced several huge hits, including the unstoppable (and irresistibly clever) "No More Lies," which became a Top Ten pop hit; its follow-up, "Nicety"; and the R&B/dance hit "Keep Watchin'." The real gems on this set, however, are the slow jams. The smoldering "Something in My Heart" became a hit well over a year after the album's release, and other tracks such as "Silly Love Song," "Close to Me," and "If?" are just as good. -

No Bitin' Allowed a Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All Of

20 Tex. Intell. Prop. L.J. 115 Texas Intellectual Property Law Journal Fall, 2011 Article NO BITIN’ ALLOWED: A HIP-HOP COPYING PARADIGM FOR ALL OF US Horace E. Anderson, Jr.a1 Copyright (c) 2011 Intellectual Property Law Section of the State Bar of Texas; Horace E. Anderson, Jr. I. History and Purpose of Copyright Act’s Regulation of Copying 119 II. Impact of Technology 126 A. The Act of Copying and Attitudes Toward Copying 126 B. Suggestions from the Literature for Bridging the Gap 127 III. Potential Influence of Norms-Based Approaches to Regulation of Copying 129 IV. The Hip-Hop Imitation Paradigm 131 A. Structure 131 1. Biting 131 2. Beat Jacking 133 3. Ghosting 135 4. Quoting 136 5. Sampling 139 B. The Trademark Connection 140 C. The Authors’ Rights Connection 142 D. The New Style - What the Future of Copyright Could Look Like 143 V. Conclusion 143 VI. Appendix A 145 VII. Appendix B 157 VIII. Appendix C 163 *116 Introduction I’m not a biter, I’m a writer for myself and others. I say a B.I.G. verse, I’m only biggin’ up my brother1 It is long past time to reform the Copyright Act. The law of copyright in the United States is at one of its periodic inflection points. In the past, major technological change and major shifts in the way copyrightable works were used have rightly led to major changes in the law. The invention of the printing press prompted the first codification of copyright. The popularity of the player piano contributed to a reevaluation of how musical works should be protected.2 The dawn of the computer age led to an explicit expansion of copyrightable subject matter to include computer programs.3 These are but a few examples of past inflection points; the current one demands a similar level of change. -

![3. SMACK THAT – EMINEM (Feat. Eminem) [Akon:] Shady Convict](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1496/3-smack-that-eminem-feat-eminem-akon-shady-convict-2571496.webp)

3. SMACK THAT – EMINEM (Feat. Eminem) [Akon:] Shady Convict

3. SMACK THAT – EMINEM thing on Get a little drink on (feat. Eminem) They gonna flip for this Akon shit You can bank on it! [Akon:] Pedicure, manicure kitty-cat claws Shady The way she climbs up and down them poles Convict Looking like one of them putty-cat dolls Upfront Trying to hold my woodie back through my Akon draws Slim Shady Steps upstage didn't think I saw Creeps up behind me and she's like "You're!" I see the one, because she be that lady! Hey! I'm like ya I know lets cut to the chase I feel you creeping, I can see it from my No time to waste back to my place shadow Plus from the club to the crib it's like a mile Why don't you pop in my Lamborghini away Gallardo Or more like a palace, shall I say Maybe go to my place and just kick it like Plus I got pal if your gal is game TaeBo In fact he's the one singing the song that's And possibly bend you over look back and playing watch me "Akon!" [Chorus (2X):] [Akon:] Smack that all on the floor I feel you creeping, I can see it from my Smack that give me some more shadow Smack that 'till you get sore Why don't you pop in my Lamborghini Smack that oh-oh! Gallardo Maybe go to my place and just kick it like Upfront style ready to attack now TaeBo Pull in the parking lot slow with the lac down And possibly bend you over look back and Convicts got the whole thing packed now watch me Step in the club now and wardrobe intact now! I feel it down and cracked now (ooh) [Chorus] I see it dull and backed now I'm gonna call her, than I pull the mack down Eminem is rollin', d and em rollin' bo Money -

MUS 17 - Week 6, May 6 to Do, May 6

MUS 17 - Week 6, May 6 To do, May 6 1. Discuss remaining writing assignments: ◦ Writing assignment #3, due 5/27 via TritonEd at noon. Note that there is no lecture on this day, but the writing assignment is still due. Final paper is due 6/7 at noon. ◦ Final paper (annotated bib) 2. Research and writing strategies for remaining papers 3. Listening ID practice 4. Review last week's lecture 5. New material: mainstreaning and undergrounding in the second golden age. ◦ Advertising, The Source ◦ West Coast: Dre, Snoop, Tupac, Pharcyde, Freestyle Fellowship, Boss ◦ East Coast: Biggie, Nas, Lil Kim, Wu Tang, Mobb Deep Research strategies Developing a research question (final paper): • "Research" is just developing the courage to listen to the voices inside you that want to know more. You may have to do some work to quiet those other voices. • Think back to lectures, remember those moments where something really interest you. This has to be something that you want to know more about, and that is related to hip hop music (somehow). • Listen to music you like, keep an open mind, and see what questions it provokes. For finding "sources" (final paper): • roger.ucsd.edu -- the library catalog. • jstor.org -- the University pays to subscribe to services like this so that you can get access to academic research journalism • best of all: Peter Mueller. Set up a meeting with him and just state your question. "I want to know more about ... " will always yield useful results. When you're writing about the music (both papers), think back to our analytical categories: • Timbre, mode, pocket, kick/snare/ride, the feel/quality of a rapper's flow, the intricacy of the rhyme schemes, where and when the sampled content comes from, etc. -

Snoop Dogg Snoop Dogg Mp3, Flac, Wma

Snoop Dogg Snoop Dogg mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Snoop Dogg Country: US Released: 2000 MP3 version RAR size: 1120 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1282 mb WMA version RAR size: 1300 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 289 Other Formats: XM MMF MP1 MPC DXD AUD APE Tracklist Hide Credits Doggystyle 1 Bathtub 2 G Funk Intro 3 Gin & Juice 4 Tha Shiznit 5 Lodi Dodi 6 Murder Was The Case 7 Serial Killa 8 Who Am I (What's My Name) 9 For All My Niggaz & Bitches 10 Aint No Fun (If The Homies Cant Have None) 11 Doggy Dogg World 12 Gz And Hustlas 13 Pump Pump Tha Doggfather 14 Intro 15 Doggfather 16 Ride 4 Me 17 Up Jump Tha Boogie 18 Freestyle Conversation 19 When I Grow Up 20 Gold Rush 21 Snoop Bounce 22 (Tear 'Em Off) Me & My Doggz 23 You Thought 24 Vapors 25 Groupie 26 2001 27 Sixx Minutes Da Game Is To Be Sold, Not To Be Told 28 Snoop World 29 I Can't Take The Heat 30 Woof! 31 Gin & Juice II 32 Show Me Love 33 Hustle And Ball 34 Don't Let Go 35 Tru Tank Dogs 36 Whatcha Gon Do 37 Still A G Thang 38 20 Dollars To My Name 39 D.O.G.'s Get Lonely 2 40 Ain't Nut'in Personal 41 DP Gangsta 42 Game Of Life 43 See Ya When I Get There 44 Pay For P 45 Picture This 46 Doggz Gonna Get Ya 47 Hoes, Money (Clout) 48 Get Bout It (Rowdy) No Limit Top Dogg 49 Dolomite Intro 50 Buck 'Em 51 Trust Me 52 My Heat Goes Boom 53 Dolomite 54 Snoopafella 55 In Love With A Thug 56 G Bedtime Stories 57 Down 4 My N's 58 Betta Days 59 Something Bout Yo Bidness 60 B Please 61 Doin' Too Much 62 Gangsta Ride 63 Ghetto Symphony 64 Party With A D.P.G. -

Trustees of Boston University Through Its Publication Arion: a Journal of Humanities and the Classics Trustees of Boston University

Trustees of Boston University through its publication Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics Trustees of Boston University Rhetoric of Reputation: Protagoras' Statement, Snoop Doggy Dogg's Flow Author(s): Spencer Hawkins Source: Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics, Vol. 24, No. 1 (Spring/Summer 2016), pp. 129-150 Published by: Trustees of Boston University; Trustees of Boston University through its publication Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/arion.24.1.0129 Accessed: 05-10-2016 22:02 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Trustees of Boston University through its publication Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics, Trustees of Boston University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics This content downloaded from 141.211.4.224 on Wed, 05 Oct 2016 22:02:38 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Rhetoric of Reputation: Protagoras’ Statement, Snoop Doggy Dogg’s Flow SPENCER HAWKINS Reputation can decide our station in life, and it is so often out of our control. This anxiety-induc- ing situation can leave us obsessed with the project of controlling our reputations. -

Snoop Doggy Dogg Gin and Juice Mp3, Flac, Wma

Snoop Doggy Dogg Gin And Juice mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Gin And Juice Country: US Released: 1994 Style: Gangsta MP3 version RAR size: 1673 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1800 mb WMA version RAR size: 1554 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 310 Other Formats: MP4 AIFF AA AC3 FLAC XM RA Tracklist 1 Gin And Juice (Radio Version - No Indo) 3:41 2 Gin And Juice (Radio Version) 3:38 3 Gin And Juice (Laid Back Mix) 4:48 4 Gin And Juice (Laid Back Radio Mix) 3:40 Credits Producer – Dr. Dre Vocals [Additional] – Heney Loc, Jewell*, Sean "Barney Rubble" Thomas* Written-By – Snoop Doggy Dogg* Notes Promo Copy - Not For Sale Issued in standard jewel case with rear insert. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Death Row Snoop A8316T, Gin And Juice Records , A8316T, Doggy UK 1994 6544-95949-0 (12") Interscope 6544-95949-0 Dogg* Records Death Row Snoop A8316CD, Gin And Juice Records , A8316CD, Doggy Europe 1994 6544-95949-2 (CD, Single) Interscope 6544-95949-2 Dogg* Records Death Row Snoop Gin & Juice Records , 6544-95949-2 Doggy (CD, Single, 6544-95949-2 Australia 1994 Interscope Dogg* Car) Records Death Row Snoop Gin And Juice Records , 98318-4 Doggy 98318-4 US 1994 (Cass, Single) Interscope Dogg* Records Snoop Gin And Juice Interscope 6544-95951-0 Doggy 6544-95951-0 US 1994 (12") Records Dogg* Related Music albums to Gin And Juice by Snoop Doggy Dogg Snoop Doggy Dogg - What's My Name? Snoop Dogg - Doggy Dogg World Snoop Dogg - Doggy Style Hits Snoop Doggy Dogg - Death Row's Snoop Doggy Dogg Greatest Hits Dr. -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Various Aritsts – American Girl Fanzine

Various Aritsts – American Girl Fanzine Soundtrack – Begin Again (Deluxe) Jesse McCartney – In Technicolor New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!!! And more… UNI14-27 UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: ERIC CLAPTON / THE BREEZE: AN APPRECIATION OF J.J. CALE Cat. #: 554082 Price Code: SP Order Due: July 3, 2014 Release Date: July 29, 2014 File: Rock Genre Code: 37 Box Lot: 25 8 22685 54084 4 Artist/Title: ERIC CLAPTON / THE BREEZE: AN APPRECIATION OF J.J. CALE [2 LP] Cat. #: 559621 Price Code: CL Order Due: July 3, 2014 Release Date: July 29, 2014 File: Rock Genre Code: 37 Box Lot: 25 8 22685 59625 4 Eric Clapton has often stated that JJ Cale is one of the single most important figures in rock history, a sentiment echoed by many of his fellow musicians. Cale’s influence on Clapton was profound, and his influence on many more of today’s artists cannot be overstated. To honour JJ’s legacy, a year after his passing, Clapton gathered a group of like-minded friends and musicians for Eric Clapton & Friends: The Breeze, An Appreciation of JJ Cale scheduled to be released July 29, 2014. With performances by Clapton, Mark Knopfler, John Mayer, Willie Nelson, Tom Petty, Derek Trucks and Don White, the album features 16 beloved JJ Cale songs and is named for the 1972 single “Call Me The Breeze.” 1. Call Me The Breeze (Vocals Eric Clapton) TRACKLISTING 9.