Wham! Bam! Pam!: Pam Grier As Hot Action Babe and Cool Action Mama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Life

STUDENT LIFE HOMECOMING Homecoming is a unique tradition at the University of Rhode Island celebrated by students and alumni of all ages. On a large field people, cars, trucks, and moving vans stretch for miles. Music blares in all directions. The smell of the barbecue and the sound of beer cans cracking open fills the air. There is laughter, singing, dancing, and fun. Both students and alumni anticipate this October day for months. At the same are time there shouts in the background as friends and family cheer on the Rhody Rams as they the rival challenge Maine Bears. The game begins with the recognition of past football players and marching band members. Half-time continues this support of URI students and alumni by honoring the Homecoming King and Queen, Jeremiah Stone and Melanie Mecca. These two individuals are crowned for their outstanding campus and community involvement and their upstanding personalities. Whether celebrating at the football stadium or in the field behind it. Homecoming is a memorable event for all. Sorority sisters and fraternity brothers reunite. Old friends rebuild bonds with those they have not seen in years. Recent graduates come back with their "real world" stories and relive their college experiences. Older alumni witness the remarkable changes that have occurred at the University. Homecoming reminds us all of the days long gone, but not forgotten. It keeps the memories and experiences of the University of Rhode Island alive, in triendb and family. What is being trashed, posessions stolen, and a wad "down-the-line? of money in your pocket which was Down the line has many different generated from the collection at the door. -

HOLLYWOOD FILMS in the NON-WESTERN WORLD: What Are the Criteria Followed by the Chinese Government When Choosing Hollywood Film Imports?

HOLLYWOOD FILMS IN THE NON-WESTERN WORLD: What Are the Criteria Followed by the Chinese Government When Choosing Hollywood Film Imports? Marta Forns Escudé 2013/38 Marta Forns Escudé Institut Barcelona d’Estudis Internacionals (IBEI) [email protected] ISSN: 1886-2802 IBEI WORKING PAPERS 2013/38 Hollywood Films in the Non-Western World: What Are the Criteria Followed by the Chinese Government When Choosing Hollywood Film Imports? © Marta Forns Escudé © IBEI, de esta edición Edita: CIDOB edicions Elisabets, 12 08001 Barcelona Tel. 93 302 64 95 Fax. 93 302 21 18 E-mail: [email protected] URL: www.cidob.org Depósito legal: B-21.147-2006 ISSN:1886-2802 Imprime: CTC, S.L. Barcelona, May 2013 HOLLYWOOD FILMS IN THE NON-WESTERN WORLD: WHAT ARE THE CRITERIA FOLLOWED BY THE CHINESE GOVERNMENT WHEN CHOOSING HOLLYWOOD FILM IMPORTS? Marta Forns Escudé Abstract: This dissertation argues that the Government of the People’s Republic of China, when it made the decision to import a quota of Hollywood films in 1994 to revive the failing domestic film industry, had different possible criteria in mind. This project has studied four of them: first, importing films that gave a negative image of the United States; second, impor- ting films that featured Chinese talent or themes; third, importing films that were box office hits in the United States; and fourth, importing films with a strong technological innovation ingredient. In order to find out the most important criteria for the Chinese Government, this dissertation offers a dataset that analyzes a population of 262 Hollywood films released in the PRC between 1994 and 2010. -

Spectacle, Masculinity, and Music in Blaxploitation Cinema

Spectacle, Masculinity, and Music in Blaxploitation Cinema Author Howell, Amanda Published 2005 Journal Title Screening the Past Copyright Statement © The Author(s) 2005. The attached file is posted here with permission of the copyright owner for your personal use only. No further distribution permitted. Please refer to the journal's website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/4130 Link to published version http://www.latrobe.edu.au/screeningthepast/ Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Spectacle, masculinity, and music in blaxploitation cinema Spectacle, masculinity, and music in blaxploitation cinema Amanda Howell "Blaxploitation" was a brief cycle of action films made specifically for black audiences in both the mainstream and independent sectors of the U.S. film industry during the early 1970s. Offering overblown fantasies of black power and heroism filmed on the sites of race rebellions of the late 1960s, blaxploitation films were objects of fierce debate among social leaders and commentators for the image of blackness they projected, in both its aesthetic character and its social and political utility. After some time spent as the "bad object" of African-American cinema history,[1] critical and theoretical interest in blaxploitation resurfaced in the 1990s, in part due to the way that its images-- and sounds--recirculated in contemporary film and music cultures. Since the early 1990s, a new generation of African-American filmmakers has focused -

![Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3954/inmedia-3-2013-%C2%AB-cinema-and-marketing-%C2%BB-online-online-since-22-april-2013-connection-on-22-september-2020-603954.webp)

Inmedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online Since 22 April 2013, Connection on 22 September 2020

InMedia The French Journal of Media Studies 3 | 2013 Cinema and Marketing Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 DOI: 10.4000/inmedia.524 ISSN: 2259-4728 Publisher Center for Research on the English-Speaking World (CREW) Electronic reference InMedia, 3 | 2013, « Cinema and Marketing » [Online], Online since 22 April 2013, connection on 22 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/inmedia/524 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ inmedia.524 This text was automatically generated on 22 September 2020. © InMedia 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cinema and Marketing When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Cinema and Marketing: When Cultural Demands Meet Industrial Practices Nathalie Dupont and Joël Augros Jerry Pickman: “The Picture Worked.” Reminiscences of a Hollywood publicist Sheldon Hall “To prevent the present heat from dissipating”: Stanley Kubrick and the Marketing of Dr. Strangelove (1964) Peter Krämer Targeting American Women: Movie Marketing, Genre History, and the Hollywood Women- in-Danger Film Richard Nowell Marketing Films to the American Conservative Christians: The Case of The Chronicles of Narnia Nathalie Dupont “Paris . As You’ve Never Seen It Before!!!”: The Promotion of Hollywood Foreign Productions in the Postwar Era Daniel Steinhart The Multiple Facets of Enter the Dragon (Robert Clouse, 1973) Pierre-François Peirano Woody Allen’s French Marketing: Everyone Says Je l’aime, Or Do They? Frédérique Brisset Varia Images of the Protestants in Northern Ireland: A Cinematic Deficit or an Exclusive -

Dolemite Is My Name

DOLEMITE IS MY NAME Written by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski FINAL IN THE BLACK We hear Marvin Gaye's "What's Goin' On" playing softly. VOICE I ain't lying. People love me. INT. DOLPHIN'S - DAY CU of a beat-up record from the 1950s. On the paper cover is a VERY YOUNG Rudy, in a tuxedo. It says "Rudy Moore - BUGGY RIDE" RUDY You play this, folks gonna start hoppin' and squirmin', just like back in the day. A hand lifts the record up to the face of RUDY RAY MOORE, late '40s, black, sweet, determined. RUDY When I sang this on stage, I swear to God, people fainted! Ambulance man was picking them off the floor! When I had a gig, the promoter would warn the hospital: "Rudy's on tonight -- you're gonna be carrying bodies out of the motherfucking club!" We see that we are in a RADIO BOOTH. A sign blinks "On The Air." The DJ, ROJ, frowns at the record. ROJ "Buggy Ride"? RUDY Wasn't no small-time shit. ROJ GodDAMN, Rudy! That record's 1000 years old! I've got Marvin Gaye singin' "Let's Get It On"! I can't be playin' no "Buggy Ride." (beat) Look, I have 60 seconds. I have to cue the next tune. Hm! Rudy bites his lip and walks away. Roj tries to go back to his job. He reaches for a Sly Stone single -- when Rudy suddenly bounds back up. RUDY How about "Step It Up and Go"? That's a real catchy rhythm-and-blues number. -

Eazy-E Wut Would You Do

Wut Would You Do Eazy-E Inside the minds of real g's Death row is looked upon as the studio gangsters of the 90's A joke hahahaha in a game called 5 minutes of fame you wasted 4 minutes now you got seconds left kick it Come one come all and let me ride nigga Eazy-e cpt how the hell you figure To be the best on the west hu you? Fool locked down this is east side nigga South comton and I put it on the map So when a dog pound crip you wanna scrap And that coming straight from the ruthless gangster Eazy-e Now what would I do ha ha let's see Now I would take on sugars locked down the row Since Dre is a bitch pimp slap the hoe Now I'm seeing doubles man two dogs in a huddle Aa god dame now diggidi daze I biggidi blast On right one and smoke that ass Now corrupt don't even set trip Yelling long beach 60 blood and puppy pound Crip really doe got my nuts on your chin Well I'm all in your philly hoe So come with it fool and test your luck and I'll beat that ass now call me corrupt Now I'm creeping through the fog you Big dogg blue got my nine milla killa Hunting a dogg named snoop You can run nigga but you can't hide Eazy-e straight creeping on the east side 7 Ten-long beach south caught snoop free basin In a rock house I kicks in the door I said it before I never let no busta test me no more Bang murder was the case that they gave me Murder was the case that they gave me I'll smoke all you fools even you boo boo and your baby Murder was the case that they gave me watch out buddie boy Watch your back Yeah what would you do? What would you do if -

Snoop Dogg Wet (G-Mix) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Snoop Dogg Wet (G-Mix) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Wet (G-Mix) Country: Japan Released: 2010 MP3 version RAR size: 1785 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1621 mb WMA version RAR size: 1951 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 922 Other Formats: AU MP2 FLAC RA AC3 APE DTS Tracklist Hide Credits Wet (G-Mix) A1 Featuring – Jim Jones , Shawty Lo A2 Wet (Main) A3 Wet (Instrumental) Don't Need No Bitch B1 Featuring – Brian Honeycutt, Devin The Dude B2 That Good Platinum B3 Featuring – R. Kelly Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Snoop Dogg Vs Snoop David Guetta - Dogg Vs Capitol none Sweat (David Guetta none US 2011 David Records Remix) (File, AAC, Guetta Single, 256) Snoop Dogg Vs Snoop David Guetta - Dogg Vs none Sweat (David Guetta Parlophone none UK 2011 David Remix) (CDr, Single, Guetta Promo) Sweat (David Guetta Snoop & Afrojack Dub Priority 5099908322159 5099908322159 US 2011 Dogg Remix) (File, MP3, Records Single, 320) Snoop Snoop Dogg vs Dogg vs David Guetta - none EMI none Sweden 2011 David Sweat / Wet (CDr, Guetta Maxi, Promo) Snoop Snoop Dogg vs Doggy Style 509990 28536 2 Dogg vs David Guetta - Records , 509990 28536 2 Germany 2011 8 David Sweat (Remix) (CD, Priority 8 Guetta Single) Records Related Music albums to Wet (G-Mix) by Snoop Dogg Snoop Dogg - Sensual Seduction Snoop Dogg feat. Charlie Wilson - Peaches N Cream Snoop Dogg - Boom Snoop Dogg - Snoop Dogg / Backup Ho Snoop Dogg - Snoop Dogg Snoop Dogg - Smokefest 2 Snoop Dogg - Wet (Remixes) Snoop Dogg - Late Nights Suge Knight, Dr. -

Un Retrato De La Actriz: Pam Grier

Un retrato de la actriz: Pam Grier Escrito por Kymberly Keeton Viernes 21 de Diciembre de 2012 12:24 La actriz Pam Grier, mejor conocida por sus papeles en películas del género blaxploitation en los años 70, regresa con una nota sobre avance, feminismo, vida, amor, sexualidad e independencia. Estos mensajes son escritos en una lengua vernácula fácil para sus fans. Su autobiografía, My Life in Three Acts: Foxy, echa una mirada fascinante a la vida y legado de Grier. Durante el verano de 2010 hizo una gira por los Estados Unidos presentando el libro. Para Grier, fue “la gira del gran abrazo consolador”. La actriz Afroamericana nació en Winston-Salem, Carolina del Norte. La madre de Pam Grier era enfermera, y su padre era sargento técnico de la fuerza aérea de Estados Unidos. Tiene una hermana y un hermano. Como resultado de vivir en una familia militar, los Grier se mudan a menudo. El libro inicia con Pam Grier hablando sobre su descubrimiento de que los Afroamericanos y los Blancos no se comunicaban entre sí en los años sesenta. 1 / 5 Un retrato de la actriz: Pam Grier Escrito por Kymberly Keeton Viernes 21 de Diciembre de 2012 12:24 La actriz habla abiertamente sobre el racismo en los Estados Unidos mientras crecía en Denver, Colorado. “Te das cuenta que era una opresión {durante esos tiempos} … me daba cuenta de cómo los padres ocultaban su ira para salvar a sus familias. También podías ver que personas de otra raza te veían diferente. En aquel entonces, los padres te decían por qué otras gente tenía prejuicios sobre ti”. -

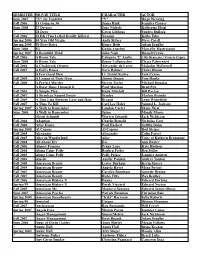

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V" for Vendetta "V" Hugo Weaving Fall 2006 13 Going on 30 Jenna Rink Jennifer Garner Sum 2008 27 Dresses Jane Nichols Katherine Heigl ? 28 Days Gwen Gibbons Sandra Bullock Fall 2006 2LDK (Two Lethal Deadly Killers) Nozomi Koike Eiko Spring 2006 40 Year Old Virgin Andy Stitzer Steve Carell Spring 2005 50 First Dates Henry Roth Adam Sandler Sum 2008 8½ Guido Anselmi Marcello Mastroianni Spring 2007 A Beautiful Mind John Nash Russell Crowe Fall 2006 A Bronx Tale Calogero 'C' Anello Lillo Brancato / Francis Capra Sum 2008 A Bronx Tale Sonny LoSpeecchio Chazz Palmenteri Fall 2006 A Clockwork Orange Alexander de Large Malcolm McDowell Fall 2007 A Doll's House Nora Helmer Claire Bloom ? A Few Good Men Lt. Daniel Kaffee Tom Cruise Fall 2005 A League of Their Own Jimmy Dugan Tom Hanks Fall 2000 A Perfect Murder Steven Taylor Michael Douglas ? A River Runs Through It Paul Maclean Brad Pitt Fall 2005 A Simple Plan Hank Mitchell Bill Paxton Fall 2007 A Streetcar Named Desire Stanley Marlon Brando Fall 2005 A Thin Line Between Love and Hate Brandi Lynn Whitefield Fall 2007 A Time To Kill Carl Lee Haley Samuel L. Jackson Spring 2007 A Walk to Remember Landon Carter Shane West Sum 2008 A Walk to Remember Jaime Mandy Moore ? About Schmidt Warren Schmidt Jack Nickleson Fall 2004 Adaption Charlie/Donald Nicholas Cage Fall 2000 After Hours Paul Hackett Griffin Dunn Spring 2005 Al Capone Al Capone Rod Steiger Fall 2005 Alexander Alexander Colin Farrel Fall 2005 Alice in Wonderland Alice Voice of Kathryn Beaumont -

Film Calendar

FILM CALENDAR JULY 26 - OCTOBER 3, 2019 ONCE UPON A TIME… IN HOLLYWOOD *ON 70MM* OPENS JULY 26 JENNIFER KENT’S THE NIGHTINGALE OPENS AUGUST 16 NOIR CITY CHICAGO SEPTEMBER 6-12 GIVE ME LIBERTY A MUSIC BOX FILMS RELEASE OPENS SEPTEMBER 13 DORIS DAY WEEKEND MATINEES SEPTEMBER 15-29 Music Box Theatre 90th Anniversary Celebration August 22 - 29 Welcome TO THE MUSIC BOX THEATRE! FEATURE FILMS 5 ONCE UPON A TIME… IN HOLLYWOOD OPENS JULY 26 7 LUZ OPENS AUGUST 2 7 HONEYLAND OPENS AUGUST 9 8 THE NIGHTINGALE OPENS AUGUST 16 CHICAGO 9 AQUARELA OPENS AUGUST 30 ONSCREEN 9 GIVE ME LIBERTY OPENS SEPTEMBER 13 12 MONOS OPENS SEPTEMBER 20 A traveling exhibition of MUSIC BOX 90TH ANNIVERSARY Chicago-made film 16 INNOCENTS OF PARIS AUGUST 22 17 THE FUGITIVE AUGUST 23 18 WORLD CITY IN ITS TEENS AUGUST 24 18 DOLLY PARTON 9 TO 5ER AUGUST 24 19 MARY POPPINS SING-A-LONG AUGUST 25 19 INDIE HORROR: SOCIETY AUGUST 25 20 MUSIC BOX FILMS DOUBLE FEATURE AUGUST 27 21 AUDIENCE CHOICE DOUBLE FEATURE AUGUST 28 22 70MM: BACK TO THE FUTURE II AUGUST 29 24 THE HISTORY OF THE MUSIC BOX SERIES 28 BETTE DAVIS MATINEES 30 DORIS DAY MATINEES 30 SILENT CINEMA 08.26-08.28 32 CHICAGO FILM SOCIETY NEIGHBORHOOD 34 MIDNIGHTS SHOWCASE SCREENINGS Dunbar Park | Grant Park | Horner Park SPECIAL EVENTS Jackson Park | Margate Park | Mckinley Park 6 GALLAGHER WAY MOVIE SERIES MAY - SEPTEMBER Steelworkers Park | Wicker Park 6 DISCOVER THE HORROR JULY 27 8 RUSH: CINEMA STRANGIATO AUGUST 21 08.29-08.31 10 NOIR CITY SEPTEMBER 6-12 CHICAGO ONSCREEN FESTIVAL 11 SAY AMEN, SOMEBODY SEPTEMBER 14 & 15 Humboldt Park | Three days of local films from filmmakers 11 REELING FILM FESTIVAL OPENING SEPTEMBER 19 and film organizations from all over the city in a multi-screen 12 48 HOUR FILM PROJECT SEPTEMBER 22-25 festival celebration of movies by and about Chicago. -

Scms 2017 Conference Program

SCMS 2017 CONFERENCE PROGRAM FAIRMONT CHICAGO MILLENNIUM PARK March 22–26, 2017 Letter from the President Dear Friends and Colleagues, On behalf of the Board of Directors, the Host and Program Committees, and the Home Office staff, let me welcome everyone to SCMS 2017 in Chicago! Because of its Midwestern location and huge hub airport, not to say its wealth of great restaurants, nightlife, museums, shopping, and architecture, Chicago is always an exciting setting for an SCMS conference. This year at the Fairmont Chicago hotel we are in the heart of the city, close to the Loop, the river, and the Magnificent Mile. You can see the nearby Millennium Park from our hotel and the Art Institute on Michigan Avenue is but a short walk away. Included with the inexpensive hotel rate, moreover, are several amenities that I hope you will enjoy. I know from previewing the program that, as always, it boasts an impressive display of the best, most stimulating work presently being done in our field, which is at once singular in its focus on visual and digital media and yet quite diverse in its scope, intellectual interests and goals, and methodologies. This year we introduced our new policy limiting members to a single role, and I am happy to say that we achieved our goal of having fewer panels overall with no apparent loss of quality in the program or member participation. With this conference we have made presentation abstracts available online on a voluntary basis, and I urge you to let them help you navigate your way through the program. -

The Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Birth of Funk Culture

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2013 Funk My Soul: The Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. And the Birth of Funk Culture Domenico Rocco Ferri Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ferri, Domenico Rocco, "Funk My Soul: The Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. And the Birth of Funk Culture" (2013). Dissertations. 664. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/664 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2013 Domenico Rocco Ferri LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO FUNK MY SOUL: THE ASSASSINATION OF DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. AND THE BIRTH OF FUNK CULTURE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN HISTORY BY DOMENICO R. FERRI CHICAGO, IL AUGUST 2013 Copyright by Domenico R. Ferri, 2013 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Painstakingly created over the course of several difficult and extraordinarily hectic years, this dissertation is the result of a sustained commitment to better grasping the cultural impact of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s life and death. That said, my ongoing appreciation for contemporary American music, film, and television served as an ideal starting point for evaluating Dr.