Dissertation Full Draft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unicef Book No Photo

Front Cover: UNICEF/EAPRO/Thierry Falise ADULT WARS, CHILD SOLDIERS Voices of Children Involved in Armed Conflict in the East Asia and Pacific Region C ONTENTS Chapter 1: This Study 7 Introduction 8 Methodology 10 Legal Standards to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers 12 Status of Ratification of Key International Treaties 14 Child Soldiers Map 15 Chapter 2: Voices of Child Soldiers 19 Section 1: How We Became Involved 23 "The militia threatened to kill me…" 24 "I was dragged out of my house…" 25 "I joined to serve the people…" 26 "I think soldiers are very beautiful…" 29 "I had no parents to look after me…" 30 "My parents couldn’t afford to send me to school…" 31 Section 2: Our Experiences as Child Soldiers 35 "I had about two weeks of training…" 36 "Yes, I have heard of the Geneva Conventions…" 39 "Don’t steal, don’t talk to girls or have sex…" 41 "They ordered us to rape…" 43 "My jobs were to take care of security, cooking and carrying orders…" 44 "No, I’m not being paid…" 47 "Yes, we have doctors…" 50 "Kill or be killed…" 52 "It was a good experience for me…" 56 "A good age for youth to join the army is 18..." 58 Section 3: Coping with Our Pasts and Looking Ahead 63 "I have bad dreams of killing people…" 64 "Sometimes now I get very angry…" 66 "I want to become one of the successful people in life…" 67 Chapter 3: Conclusion- Children Caught in the Crossfire of Adult Wars 73 Children Involved in Armed Conflict in EAP Case Studies Project: Guidelines for Case Studies 76 Acknowledgments 81 Visna is registered in the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces as an adult soldier. -

Chart Book Template

Real Chart Page 1 become a problem, since each track can sometimes be released as a separate download. CHART LOG - F However if it is known that a track is being released on 'hard copy' as a AA side, then the tracks will be grouped as one, or as soon as known. Symbol Explanations s j For the above reasons many remixed songs are listed as re-entries, however if the title is Top Ten Hit Number One hit. altered to reflect the remix it will be listed as would a new song by the act. This does not apply ± Indicates that the record probably sold more than 250K. Only used on unsorted charts. to records still in the chart and the sales of the mix would be added to the track in the chart. Unsorted chart hits will have no position, but if they are black in colour than the record made the Real Chart. Green coloured records might not This may push singles back up the chart or keep them around for longer, nevertheless the have made the Real Chart. The same applies to the red coulered hits, these are known to have made the USA charts, so could have been chart is a sales chart and NOT a popularity chart on people’s favourite songs or acts. Due to released in the UK, or imported here. encryption decoding errors some artists/titles may be spelt wrong, I apologise for any inconvenience this may cause. The chart statistics were compiled only from sales of SINGLES each week. Not only that but Date of Entry every single sale no matter where it occurred! Format rules, used by other charts, where unnecessary and therefore ignored, so you will see EP’s that charted and other strange The Charts were produced on a Sunday and the sales were from the previous seven days, with records selling more than other charts. -

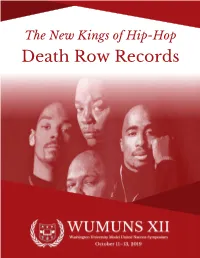

Death Row Records

The New Kings of Hip-Hop Death Row Records “You are now about to witness the strength of street knowledge.” —N.W.A. Contents Letter from the Director ................................................................................................... 4 Mandate .......................................................................................................................... 5 Background ...................................................................................................................... 7 Topics for Discussion ..................................................................................................... 10 East Coast vs. West Coast .................................................................................... 10 Internal Struggles................................................................................................. 11 Turmoil in Los Angeles ........................................................................................ 12 Positions ........................................................................................................................ 14 Letter from the Director Dear Delegates, Welcome to WUMUNS XII! I am a part of the class of 2022 here at Washington University in St. Louis, and I’ll be serving as your director. Though I haven’t officially declared a major yet, I’m planning on double majoring in political science and finance. I’ve been involved with Model UN since my freshman year of high school, and I have been an active participant ever since. I am also involved -

Student Life

STUDENT LIFE HOMECOMING Homecoming is a unique tradition at the University of Rhode Island celebrated by students and alumni of all ages. On a large field people, cars, trucks, and moving vans stretch for miles. Music blares in all directions. The smell of the barbecue and the sound of beer cans cracking open fills the air. There is laughter, singing, dancing, and fun. Both students and alumni anticipate this October day for months. At the same are time there shouts in the background as friends and family cheer on the Rhody Rams as they the rival challenge Maine Bears. The game begins with the recognition of past football players and marching band members. Half-time continues this support of URI students and alumni by honoring the Homecoming King and Queen, Jeremiah Stone and Melanie Mecca. These two individuals are crowned for their outstanding campus and community involvement and their upstanding personalities. Whether celebrating at the football stadium or in the field behind it. Homecoming is a memorable event for all. Sorority sisters and fraternity brothers reunite. Old friends rebuild bonds with those they have not seen in years. Recent graduates come back with their "real world" stories and relive their college experiences. Older alumni witness the remarkable changes that have occurred at the University. Homecoming reminds us all of the days long gone, but not forgotten. It keeps the memories and experiences of the University of Rhode Island alive, in triendb and family. What is being trashed, posessions stolen, and a wad "down-the-line? of money in your pocket which was Down the line has many different generated from the collection at the door. -

The Endless Fall of Suge Knight He Sold America on a West Coast Gangster Fantasy — and Embodied It

The Endless Fall of Suge Knight He sold America on a West Coast gangster fantasy — and embodied it. Then the bills came due BY MATT DIEHL July 6, 2015 Share Tweet Share Comment Email This could finally be the end of the road for Suge Knight, who helped bring West Coast gangsta rap to the mainstream. Photo illustration by Sean McCabe On March 20th, inside the high-security wing of Los Angeles' Clara Shortridge Foltz Criminal Justice Center, the man once called "the most feared man in hip-hop" is looking more like the 50-year-old with chronic health issues that he is. Suge Knight sits in shackles, wearing an orange prison jumpsuit and chunky glasses, his beard flecked with gray, listening impassively. It's the end of the day's proceedings, and Judge Ronald S. Coen is announcing the bail for Knight, who is facing charges of murder, attempted murder and hit-and-run: "In this court's opinion, $25 million is reasonable, and it is so set." A gasp erupts from Knight's row of supporters — some of whom sport red clothing or accessories, a color associated with the Bloods and Piru street gangs. The most shocked are Knight's family, who have attended nearly all of his court dates: his parents, along with his fiancee, Toilin Kelly, and sister Karen Anderson. "He's never had a bail like that before!" Anderson exclaims. SIDEBAR 30 Most Embarrassing Rock-Star Arrests » As attendees exit and Knight is escorted out by the bailiffs, Knight's attorney Matthew Fletcher pleads with Coen to reconsider. -

Traditional Funk: an Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio

University of Dayton eCommons Honors Theses University Honors Program 4-26-2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Caleb G. Vanden Eynden University of Dayton Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses eCommons Citation Vanden Eynden, Caleb G., "Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio" (2020). Honors Theses. 289. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses/289 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Abstract Recognized nationally as the funk capital of the world, Dayton, Ohio takes credit for birthing important funk groups (i.e. Ohio Players, Zapp, Heatwave, and Lakeside) during the 1970s and 80s. Through a combination of ethnographic and archival research, this paper offers a pedagogical approach to Dayton funk, rooted in the styles and works of the city’s funk legacy. Drawing from fieldwork with Dayton funk musicians completed over the summer of 2019 and pedagogical theories of including black music in the school curriculum, this paper presents a pedagogical model for funk instruction that introduces the ingredients of funk (instrumentation, form, groove, and vocals) in order to enable secondary school music programs to create their own funk rooted in local history. -

Anglophone Music As Poetry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Croatian Digital Thesis Repository University of Rijeka Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences in Rijeka Department of English Matea Lacmanović: Anglophone Music as Poetry Mentor: Lovorka Gruić Grmuša, PhD Rijeka, July 2015 1 Abstract Literature as a whole is usually divided into poetry, prose and drama (Solar 2006: 154) with fairly clear boundaries between them. When it comes to their subdivision and definition of specific literature and art type, the boundaries become unclear and many questions arise. One of the most difficult questions to answer is what poetry is and which criteria must be met in order for some work to be classified as poetry. It is known that authors such as Shakespeare, Byron, Cummings or Angelou are poets and their work is interpreted as poetry. However, can the circle of poetry and art be expanded to similar forms such as contemporary music? That is the topic of this thesis – analysis, explanation and specific examples of modern song lyrics which can be viewed as poetry and something more valuable in the art context than it actually is due to the commercialization of music. With songs performed by Tupac, Garbage, Leonard Cohen, Bill Withers and various artists who belong to different music genres and eras, poetry is broadened and upgraded to the 21st century level. Key words: Anglophone music, music, poetry, lyrics, analysis, literature, art, contemporary, modern, intermediation, authorship 2 Table of Contents Abstract -

A Stylistic Analysis of 2Pac Shakur's Rap Lyrics: in the Perpspective of Paul Grice's Theory of Implicature

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature Christopher Darnell Campbell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Christopher Darnell, "A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2130. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2130 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English: English Composition by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 Approved.by: 7=12 Date Bruce Golden, English ABSTRACT 2pac Shakur (a.k.a Makaveli) was a prolific rapper, poet, revolutionary, and thug. His lyrics were bold, unconventional, truthful, controversial, metaphorical and vulgar. -

Pt.BI ISHTAR ~IKAIBKRS

ASCAP "S 2006 DART CLADI Pt.BI ISHTAR ~IKAIBKRS WiD AFFILIATED FOREIG& SOCIETIKS 3 OLC&IE I OF III P U B L I S H E R .357 PUBLISHING (A) S1DE UP MUSIC $$ FAR BEYOND ENTERTAINMENT $3.34 CHANGE OF THE BEAST ? DAT I SMELL MUS1C 'NANA PUDDIN PUBL1SHING A & N MUSIC CORP A & R MUSIC CO A A B A C A B PUBLISH1NG A A KLYC 4 A A P PUBLISHING A AL1KE PUBLiSHING A ALIKES MUSIC PUBLISHING A AND F DOGZ MUSIC A AND G NEALS PUBLiSHER A AND L MUS1C A AND S MUSICAL WORKS AB& LMUSIC A B A D MUZIC PUBLISHING A B ARPEGGIO MUSIC ABCG I ABCGMUSIC A B GREER PUBLISH1NG A B REAL MUSIC PUBLISHING A B U MUSIC A B WILLIS MUS1C A BAGLEY SONG COMPANY A BALLISTIC MUSIC A BETTER HISTORY PUBLISH1NG A BETTER PUBL1SHING COMPANY A BETTER TOMORROM A BIG ATT1TUDE INC A BIG F-YOU TO THE RHYTHM A BILL DOUGLAS MUSIC A BIRD AND A BEAR PUBLISHING A BLACK CLAN 1NC A BLONDE THING PUBLISHING A BOCK PUBLISHING A BOMBINATION MUSIC A BOY AND HIS DOG A BOY NAMED HO A BRICK CALLED ALCOHOL MUSIC A BROOKLYN PROJECT A BROS A BUBBA RAMEY MUSIC A BURNABLE PUBLISHING COMPANY A C DYENASTY ENT A CARPENTER'S SON A CAT NAMED TUNA PUBLISHING A CHUNKA MUSIC A CIRCLE OF FIFTHS MUSIC A CLAIRE MlKE MUSIC A CORDIS MUSIC A CREATI VE CHYLD ' PUB L I SHING A CREATIVE RHYTHM A CROM FLIES MUSIC INC A .CURSIVE MEMDR1ZZLE A D D RECORDiNGS A D G MUSICAL PUBLISHING INC A D HEALTHFUL LIFESTYLES A D SIMPSON OWN A D SMITH PUBLISHING P U B L I S H E R A D TERROBLE ENT1RETY A D TUTUNARU PUBLISHING A DAISY IN A JELLYGLASS A DAY XN DECEMBER A DAY XN PARIS MUSIC A DAY W1TH KAELEY CLAIRE A DELTA PACIFIC PRODUCTION A DENO -

Eazy-E Wut Would You Do

Wut Would You Do Eazy-E Inside the minds of real g's Death row is looked upon as the studio gangsters of the 90's A joke hahahaha in a game called 5 minutes of fame you wasted 4 minutes now you got seconds left kick it Come one come all and let me ride nigga Eazy-e cpt how the hell you figure To be the best on the west hu you? Fool locked down this is east side nigga South comton and I put it on the map So when a dog pound crip you wanna scrap And that coming straight from the ruthless gangster Eazy-e Now what would I do ha ha let's see Now I would take on sugars locked down the row Since Dre is a bitch pimp slap the hoe Now I'm seeing doubles man two dogs in a huddle Aa god dame now diggidi daze I biggidi blast On right one and smoke that ass Now corrupt don't even set trip Yelling long beach 60 blood and puppy pound Crip really doe got my nuts on your chin Well I'm all in your philly hoe So come with it fool and test your luck and I'll beat that ass now call me corrupt Now I'm creeping through the fog you Big dogg blue got my nine milla killa Hunting a dogg named snoop You can run nigga but you can't hide Eazy-e straight creeping on the east side 7 Ten-long beach south caught snoop free basin In a rock house I kicks in the door I said it before I never let no busta test me no more Bang murder was the case that they gave me Murder was the case that they gave me I'll smoke all you fools even you boo boo and your baby Murder was the case that they gave me watch out buddie boy Watch your back Yeah what would you do? What would you do if -

Flows at Radio

VOL. LIX, NO. 29 Newspaper $3.95 Inside: Grammys Move To New York City THE ENTERTAINMENT TRADE MAGAZINE Decca’s Frazier River Flows at Radio o 82791 19360 4 37 VOL. LIX, NO. 29 MARCH 30, 1996 STAFF rcwi«i;aawmga GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher KEITH ALBERT POP SINGLE THE ENTERTAINMENT TRADE MAGAZINE Exec. V.PJGeneral Manager Always Be My Baby M.R. MARTINEZ Managing Editor Mariah Carey EDITORIAL (Columbia) Los Angeles JOHN GOFF GIL ROBERTSON IV DAINA DARZIN HECTOR RESENDEZ. Latin Edtor URBAN SINGLE Nashville Cover Story WENDY NEWCOMER All Things... The New York Joe The Frazier River Flows J.S. GAER CHART RESEARCH (Island) Angeles Frazier River frontman Danny Frazier had a plan for his group of eclectic Los BRIAN PARMELLY musicians. He’d turn a saloon band into an act that would get signed to a major ZIV TONY RUIZ label. Doesn’t sound terribly original or uncommon, but the Decca recording act RAP SINGLE PETER FIRESTONE went from the River Saloon in Cincinnati, OH to a spot on the Cosh Box Country Nashville \A£>o-Hah! Got You... GAIL FRANCESCHI Singles chart and has been traveling the nation making folks at country radio spin MARKETING/ADVERTISING Busta Rhymes Nashville editor the single “She Got What She Deserves.” Wendy Newcomer Los Angeles (Elektra) talks with Frazier about the odyssey and the group’s prospects. FFiANK HIGGINBOTHAM JOHN RHYS —see page 5 BOB CASSELL Nashville COUNTRY SINGLE TED RANDALL Take A Stroll Near Hollywood And Vine New York You Can Feel Bad NOEL ALBERT Capitol New Media has, well, reinvented the famous intersection of Hollywood CIRCULATION Patty Loveless Arid Vine. -

Still Black Still Strong

STIll BLACK,STIll SfRONG l STILL BLACK, STILL STRONG SURVIVORS Of THE U.S. WAR AGAINST BLACK REVOlUTIONARIES DHORUBA BIN WAHAD MUMIA ABU-JAMAL ASSATA SHAKUR Ediled by lim f1elcher, Tonoquillones, & Sylverelolringer SbIII01EXT(E) Sentiotext(e) Offices: P.O. Box 629, South Pasadena, CA 91031 Copyright ©1993 Semiotext(e) and individual contributors. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 978-0-936756-74-5 1098765 ~_.......-.;,;,,~---------:.;- Contents DHORUDA BIN W"AHAD WARWITIllN 9 TOWARD RE'rHINKING SEIl'-DEFENSE 57 THE CuTnNG EDGE OF PRISONTECHNOLOGY 77 ON RACISM. RAp AND REBElliON 103 MUM<A ABU-JAMAL !NrERVIEW FROM DEATH Row 117 THE PRIsON-HOUSE OF NATIONS 151 COURT TRANSCRIPT 169 THE MAN MALCOLM 187 P ANIllER DAZE REMEMBERED 193 ASSATA SHAKUR PRISONER IN THE UNITED STATES 205 CHRONOLOGY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 221 FROM THE FBI PANTHER FILES 243 NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS 272 THE CAMPAIGN TO FREE BLACK POLITICALPRISONERS 272 Contents DHORUBA BIN "W AHAD WAKWITIllN 9 TOWARD REnnNKINO SELF-DEFENSE 57 THE CurnNG EOOE OF PRISON TECHNOLOGY 77 ON RACISM, RAp AND REBEWON 103 MUMIA ABU-JAMAL !NrERVIEW FROM DEATH Row 117 THE PRIsoN-HOUSE OF NATIONS 151 COURT TRANSCRIPT 169 THE MAN MALCOLM 187 PANTHER DAZE REMEMBERED 193 ASSATA SHAKUR PJusONER IN THE UNITED STATES 205 CHRONOLOGY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 221 FROM THE FBI PANTHER FILES 243 NOTES ON CONTRmUTORS 272 THE CAMPAIGN TO FREE BUCK POLITICAL PRISONERS 272 • ... Ahmad Abdur·Rahmon (reIeo,ed) Mumio Abu·lomol (deoth row) lundiolo Acoli Alberlo '/lick" Africa (releosed) Ohoruba Bin Wahad Carlos Perez Africa Chorl.. lim' Africa Can,uella Dotson Africa Debbi lim' Africo Delberl Orr Africa Edward Goodman Africa lonet Halloway Africa lanine Phillip.