Hindu Nationalists and Local History: from Ideology to Local Lore Daniela Berti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Secrets of RSS

Secrets of RSS DEMYSTIFYING THE SANGH (The Largest Indian NGO in the World) by Ratan Sharda © Ratan Sharda E-book of second edition released May, 2015 Ratan Sharda, Mumbai, India Email:[email protected]; [email protected] License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-soldor given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person,please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and didnot purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to yourfavorite ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hardwork of this author. About the Book Narendra Modi, the present Prime Minister of India, is a true blue RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or National Volunteers Organization) swayamsevak or volunteer. More importantly, he is a product of prachaarak system, a unique institution of RSS. More than his election campaigns, his conduct after becoming the Prime Minister really tells us how a responsible RSS worker and prachaarak responds to any responsibility he is entrusted with. His rise is also illustrative example of submission by author in this book that RSS has been able to design a system that can create ‘extraordinary achievers out of ordinary people’. When the first edition of Secrets of RSS was released, air was thick with motivated propaganda about ‘Saffron terror’ and RSS was the favourite whipping boy as the face of ‘Hindu fascism’. Now as the second edition is ready for release, environment has transformed radically. -

Online Supplement Part I: Individual-Level Analysis

ONLINE SUPPLEMENT PART I: INDIVIDUAL-LEVEL ANALYSIS SECTION 1: DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS AND SUBSTANTIVE EFFECTS TABLE S.1: DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS FOR VOTER ANALYSIS (UPPER CASTE SAMPLE) TABLE S.2: DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS FOR VOTER ANALYSIS (DALIT AND ADIVASI SAMPLE) TABLE S.3: VARIABLES USED IN VOTER-LEVEL ANALYSIS TABLE S.4: SHIFTS IN SIMULATED PROBABILITY OF BJP SUPPORT AMONG DALITS AND ADIVASIS (ESTIMATED FROM MODELS REPORTED IN TABLE 1) TABLE S.5: SHIFTS IN SIMULATED PROBABILITY OF SUPPORTING BJP AMONG UPPER CASTES (ESTIMATED FROM MODELS REPORTED IN TABLE 1) SECTION 2: BASIC ROBUSTNESS CHECKS TABLE S.6: NO COLLINEARITY BETWEEN EXPLANATORY VARIABLES IN INDIVIDUAL- LEVEL SAMPLES FIGURE S1: ACCOUNTING FOR INFLUENTIAL OBSERVATIONS TABLE S.7: RESULTS AMONG NON-ELITES ARE ROBUST TO EXCLUDING HIGH INFLUENCE OBSERVATIONS TABLE S.8: RESULTS AMONG ELITES ARE ROBUST TO EXCLUDING HIGH INFLUENCE OBSERVATIONS (UPPER CASTE SAMPLE) TABLE S.9: MEMBERSHIP EFFECTS ARE ROBUST TO SEPARATELY CONTROLLING FOR INDIVIDUAL POTENTIAL CONFOUNDERS (NON-ELITES) TABLE S.10: RESULTS ARE ROBUST REMAIN TO SEPARATELY CONTROLLING FOR INDIVIDUAL POTENTIAL CONFOUNDERS (ELITES) TABLE S.11: RESULTS ARE NOT AFFECTED BY CONTROLLING FOR ADDITIONAL POLICY MEASURE: (BJP OPPOSITION TO CASTE-BASED RESERVATIONS) TABLE S.12: RESULTS ARE NOT AFFECTED BY INCLUDING ADDITIONAL IDEOLOGICAL POLICY MEASURE: (SUPPORT FOR BANNING RELIGIOUS CONVERSIONS) SECTION 3: CONTROLLING FOR VOTER OPINIONS OF POLITICAL PARTIES SECTION 3A: VIEWS OF BJP PERFORMANCE TABLE S.13A: RESULTS ARE ROBUST TO CONTROLLING FOR PERSONAL SATISFACTION WITH BJP-LED CENTRAL GOVERNMENT AND POCKETBOOK INCREASES DURING BJP TENURE (NON-ELITES) 1 TABLE S.13B: RESULTS ARE ROBUST TO CONTROLLING FOR PERSONAL SATISFACTION WITH BJP-LED CENTRAL GOVERNMENT AND POCKETBOOK INCREASES DURING BJP TENURE (ELITE SAMPLE) SECTION 3B: PARTY RATINGS: BJP VS. -

Introduction

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction The Invention of an Ethnic Nationalism he Hindu nationalist movement started to monopolize the front pages of Indian newspapers in the 1990s when the political T party that represented it in the political arena, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP—which translates roughly as Indian People’s Party), rose to power. From 2 seats in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian parliament, the BJP increased its tally to 88 in 1989, 120 in 1991, 161 in 1996—at which time it became the largest party in that assembly—and to 178 in 1998. At that point it was in a position to form a coalition government, an achievement it repeated after the 1999 mid-term elections. For the first time in Indian history, Hindu nationalism had managed to take over power. The BJP and its allies remained in office for five full years, until 2004. The general public discovered Hindu nationalism in operation over these years. But it had of course already been active in Indian politics and society for decades; in fact, this ism is one of the oldest ideological streams in India. It took concrete shape in the 1920s and even harks back to more nascent shapes in the nineteenth century. As a movement, too, Hindu nationalism is heir to a long tradition. Its main incarnation today, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS—or the National Volunteer Corps), was founded in 1925, soon after the first Indian communist party, and before the first Indian socialist party. -

Religious Movements, Militancy, and Conflict in South Asia Cases from India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan

a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religious Movements, Militancy, and Conflict in South Asia cases from india, pakistan, and afghanistan 1800 K Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 Authors E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org Joy Aoun Liora Danan Sadika Hameed Robert D. Lamb Kathryn Mixon Denise St. Peter July 2012 ISBN 978-0-89206-738-1 Ë|xHSKITCy067381zv*:+:!:+:! CHARTING our future a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religious Movements, Militancy, and Conflict in South Asia cases from india, pakistan, and afghanistan Authors Joy Aoun Liora Danan Sadika Hameed Robert D. Lamb Kathryn Mixon Denise St. Peter July 2012 CHARTING our future About CSIS—50th Anniversary Year For 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed practical solutions to the world’s greatest challenges. As we celebrate this milestone, CSIS scholars continue to provide strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a bipartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and de- velop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Since 1962, CSIS has been dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. After 50 years, CSIS has become one of the world’s pre- eminent international policy institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global development and economic integration. -

The Saffron Wave Meets the Silent Revolution: Why the Poor Vote for Hindu Nationalism in India

THE SAFFRON WAVE MEETS THE SILENT REVOLUTION: WHY THE POOR VOTE FOR HINDU NATIONALISM IN INDIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Tariq Thachil August 2009 © 2009 Tariq Thachil THE SAFFRON WAVE MEETS THE SILENT REVOLUTION: WHY THE POOR VOTE FOR HINDU NATIONALISM IN INDIA Tariq Thachil, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 How do religious parties with historically elite support bases win the mass support required to succeed in democratic politics? This dissertation examines why the world’s largest such party, the upper-caste, Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has experienced variable success in wooing poor Hindu populations across India. Briefly, my research demonstrates that neither conventional clientelist techniques used by elite parties, nor strategies of ideological polarization favored by religious parties, explain the BJP’s pattern of success with poor Hindus. Instead the party has relied on the efforts of its ‘social service’ organizational affiliates in the broader Hindu nationalist movement. The dissertation articulates and tests several hypotheses about the efficacy of this organizational approach in forging party-voter linkages at the national, state, district, and individual level, employing a multi-level research design including a range of statistical and qualitative techniques of analysis. In doing so, the dissertation utilizes national and author-conducted local survey data, extensive interviews, and close observation of Hindu nationalist recruitment techniques collected over thirteen months of fieldwork. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Tariq Thachil was born in New Delhi, India. He received his bachelor’s degree in Economics from Stanford University in 2003. -

"Financial Assistance Under CSR Scheme' by ONGC/BPCL/GAIL/HPCL/IOCL

"Financial Assistance under CSR Scheme' by ONGC/BPCL/GAIL/HPCL/IOCL 1. Oil and Natural Gas Commission (ONGC) CSR projects undertaken for Scheduled caste / Scheduled tribes and other Weaker sections during last three years Rs. In Lakh Sl Project Details State Exp in2013 - Exp in Exp in No. 14 2014-15 2015-16 1 Support to King George Hospital, Vizag Andhra Pradesh 300.00 0.00 0.00 2 Construction of OP Block,Rajamundary and Medical equipment to Andhra Pradesh 79.70 0.00 0.00 AMP&NSP hospitals 3 Drinking water facility(OHSR) in Jaggarajupeta, East Godavari District Andhra Pradesh 25.00 0.00 0.00 4 Construction of Blood Bank in Government General Hospital, Kakinada Andhra Pradesh 22.00 0.00 0.00 5 Financial assistance for Cancer Screening programme and treatment at Andhra Pradesh 4.00 0.00 0.00 Rajhmundry and Kakinada as a PILOT PROJECT. 6 Construction of Shed in Burial ground at P.Polavaram Andhra Pradesh 3.48 0.00 0.00 7 For providing Solar lighting system in Ashram High School(Girls), Andhra Pradesh 2.50 0.00 0.00 Busigudem, Rampachodavaram (M) 8 For providing Solar lighting system in AUP School(Girls), Daragedda, Y. Andhra Pradesh 2.50 0.00 0.00 Ramavaram (M) 9 Financial assistance for conducting cataract surgeries in AP Andhra Pradesh 2.00 1.37 3.00 10 Financial Assistance to Provide Drinking water facility Andhra Pradesh 2.00 0.00 0.00 11 Financial assistance for providing internal CC Road in ST area of Andhra Pradesh 1.90 0.00 0.00 Challapalli (V) 12 For providing RO plant in ST Girls Hostel, Rajavommangi Andhra Pradesh 1.70 0.00 0.00 13 For providing RO plant in Ashram High School (Girls), Ameenabad Andhra Pradesh 1.70 0.00 0.00 14 For providing RO plant in Ashram High School (Girls), V. -

Elite Parties and Poor Voters

American Political Science Review Vol. 108, No. 2 May 2014 doi:10.1017/S0003055414000069 c American Political Science Association 2014 Elite Parties and Poor Voters: Theory and Evidence from India TARIQ THACHIL Yale University hy do poor people often vote against their material interests? This article extends the study of this global paradox to the non-Western world by considering how it manifests within India, W the world’s biggest democracy. Arguments derived from studies of advanced democracies (such as values voting) or of poor polities (such as patronage and ethnic appeals) fail to explain this important phenomenon. Instead, I outline a novel strategy predicated on an electoral division of labor enabling elite parties to recruit the poor while retaining the rich. Recruitment is outsourced to nonparty affiliates that provide basic services to appeal to poor communities. Such outsourcing permits the party to maintain programmatic linkages to its elite core. Empirically, I test this argument with qualitative and quantitative evidence, including a survey of more than 9,000 voters. Theoretically, I argue that this approach is best suited to elite parties with thick organizations, typically those linked to religious social movements. hy do poor people in poor countries often In this article, I present a novel strategy through support parties that do not champion their which such a balance can be struck: Elite parties de- W programmatic interests? How do parties that ploy an organizational division of labor, in which they represent elite policy interests win mass support? Con- outsource the task of mobilizing poor voters to their ventional explanations to these questions have em- nonelectoral organizational affiliates. -

Annual Report 2016-17

“Sewa hi Paramo Dharmah” Sewa International Annual Report 2016-17 SEWA INTERNATIONAL GOVERNING BODY INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE Justice M. Rama Jois (Retd.) Dr. Shankar Tatwawadi (Retd. HOD from BHU) TRUST BOARD Chairman Sh. Ramesh Mehta (Businessman) Secretary Sh. K. G. (Shyam) Parande (Social Worker) Treasurer Sh. Sanjay Hegde (Chartered Accountant) Members Sh. Bimal Kumar Kedia (Businessman) Sh. Jai Prakash Agarwal (Chairman, Surya Ind.) Sh. Srikanth Konda (IT Entrepreneur) Sh. Mukesh Aggarwal (Businessman) Sh. Ashok Goel (Chairman, Essel Propack) Sh. Pannalal Bhansali (Businessman) SEWA INTERNATIONAL INDEX INDEX Foreword Vision of Suru-ji – A Memoir Introduction CORE PROJECTS Swachh-Shikshit-Kushal Kashi Reang (Bru) Tribal Rehab Empowering Uttarakhand Sewa Kutch – Women Empowerment A Decade of Selfless Service – Akshar Bharati SUPPORTED PROJECTS Sri Vivekananda Mutthil Mission, Kerala Vanvasi Kalyan, Karnataka Samatol Foundation Jammu and Kashmir Karunaii Trust Om Shanti Dhama Maharaja Agrasen Institute of Technology Sewa Bharati, Madhya Pradesh Akhil Bharatiya Vanavasi Kalyan Ashram Shanti Niketan Hostel, Dagshai Youth For Seva Hyderabad Seva Bharati Guntur Savitribai Phule Mahila Ekatm Samaj Mandal Sewa Bharathi Tamil Nadu, Chennai Being Volunteer, Pune Seva Sahayog, Pune Divya Vidyalaya, Jawhar Samvedna Prakalp, Latur Sewa Bharathi Purbanchal, North-East Solar Plants in Odisha INTERNATIONAL PROJECTS Nepal Rehab SUCCESS STORIES Gundor Reang (Bru Rehab) Nancy Loly (Bru Rehab) Kajal (Sewa Kashi) Vijay (Sewa Kashi) Asha Devi (Sewa Uttarakhand) Rekha Devi (Sewa Uttarakhand) SHYAM PARANDE FOREWORD Secretary It is my privilege to present to you the Annual Report and audited accounts of Sewa International for the financial year 2016-17. As the new Bharat emerges keeping in tune with times, Sewa International is engaged much more consciously and actively in nation’s development to ensure that its social, economic and environmental footprint is enhanced. -

Country Advice

Country Advice India India – IND39421 – Christians – Karnataka – Bangalore – Sangh Parivar 4 November 2011 1. Please provide an update on the situation for Christians in the state of Karnataka since response number IND34452 dated 27 February 2009? Please include information about the situation in Bangalore in particular. Karnataka was the state in India with the highest number of attacks on Christians during 2009 and 2010,1 and has continued to be a high volume of attacks against Christians during 2011.2 The situation of Christians in Karnataka has reportedly deteriorated since the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won government in that state in 2008, with a subsequent rise in violence by Hindu nationalists against Christians.3 The BJP is the political wing of the Sangh Parivar, a collective of Hindu nationalist groups in India (information on the Sangh Parivar can be found in the response to Question 2). There is also information available indicating that the government does not acknowledge the level of violence against Christians,4 and that the security forces and lower judicial system are involved in this mistreatment.5 Reports were located referring to mistreatment of Christians in Karnataka during 2011 by Hindus and members of the security forces.6 Reports were also located which refer to mistreatment of Christians in Bangalore, the capital of Karnataka, during 2010 and 2011 by Hindus, Muslims and members of the security forces.7 Treatment of Christians in Karnataka 1 Howell, R. 2010, „Religion, Politics and Violence: A Report of the Hostility and Intimidation faced by Christians in India in 2010‟, International Institute for Religious Freedom website, source: Evangelical Fellowship of India, 22 December, pp. -

Seat 1 Seat 2 20001 NORTH EAST INSTITUTE OF

List of Vacant Seats (Statewise) in General Stream as on 09.08.2015 Details of Vacant College Women's College Name State Address Seat Unique Id Institute Seat 1 Seat 2 NORTH EAST INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT Opp. Gate. No.1, Rrl, Jorhat-6, 20001 Assam No Filled Vacant SCIENCE(NEIMS) Assam 20002 GOVERNMENT COLLEGE OF ART Chandigarh Sector 10C No Filled Vacant 20004 COLLEGE OF ART Delhi 20-22Tilak Marg No Vacant Vacant 20005 GOA COLLEGE OF ART Goa Altinho,Panaji - Goa403 001 No Filled Vacant ASIA PACIFIC INSTITUTE OF HOTEL 20006 Gujarat Village Bhoyani No Vacant Filled MANAGEMENT GALAXY GLOBAL EDUCATIONAL TRUSTS Shahabad-Saha Road, Nh- 20009 Haryana No Filled Vacant GROUP OF INSTITUTIONS 73,Vill. Dinarpur, Distt. Ambala 20014 BIRLA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Jharkhand Mesra, Ranchi - 835215 No Vacant Filled Nagareshwara Nagenahalli, ARMY INSTITUTE OF HOTEL MANAGEMETN 20017 Karnataka Kothanur PostHennur Bagalur No Vacant Vacant & CATERING TECHNOLOGY Road SAMBHRAM COLLEGE OF HOTEL No 36 ,Temple RoadBeml 20022 Karnataka No Vacant Vacant MANAGEMENT NagarKgf SAROSH INSTITUTE OF HOTEL Nitte Campus, Nh 48, Kodakal, 20023 Karnataka No Filled Vacant ADMINISTRATION Kannur Post Medahalli, Virgonagar, 20024 SJES COLLEGE OF MANAGEMENT STUDIES Karnataka No Filled Vacant Krpuram, Bangalore 560049 88/1, Kammanahalli,Gottigere 20026 T. JOHN COLLEGE Karnataka Post,Bannerghatta No Vacant Filled Road,Bangalore -560083 WELCOMGROUP GRADUATE SCHOOL OF Valley View, Madhava Nagar, 20028 Karnataka No Filled Vacant HOTEL ADMINISTRATION Manipal LOURDES MATHA INSTITUTE OF HOTEL Lourdes Hills, Kuttichal, 20029 MANAGEMENT AND CATERING Kerala Kattakada, No Filled Vacant TECHNOLOGY Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala SNEHACHARYA INSTITUTE OF Karuvatta North,Karuvatta 20031 Kerala No Filled Vacant MANAGEMENT & TECHNOLOGY P.O,Alappuzha Valamangalam South SREE NARAYANA GURU MEMORIAL 20032 Kerala PostThuravoor Cherthala No Vacant Vacant CATERING COLLEGE Alappuzha Kerala 688532 ST.JOSEPHS INSTITUTE OF HOTEL Choondacherry P.O., Plassanal 20033 MANAGEMENT AND CATERING Kerala No Filled Vacant Via, Kottayam Dist. -

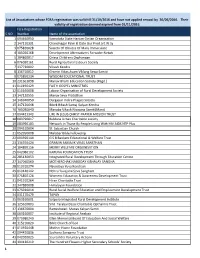

S.NO Fcra Registration Number Name of the Association 1 094640050

List of Associations whose FCRA registration was valid till 31/10/2016 and have not applied renwal by 30/06/2016. Their validity of registration deemed expired from 01/11/2016. Fcra Registration S.NO Number Name of the association 1 094640050 Karnataka State Harijan Girijan Organisation 2 147110331 Chandnagar Palm & Date Gur Prod.art.W.Sy 3 075820028 Society Of Oblates Of Mary Immaculate 4 105020168 Development Alternativers Forwider Netwk 5 104860017 Orissa Childrens Orphanage 6 076030161 Rural Agricultural Labours Society 7 337730002 Vikash Kendra 8 136710012 Gramin Vikas Avam Viklang Sewa Samiti 9 075850234 WISDOM EDUCATIONAL TRUST 10 231661098 Manav Bharti Education Society (Regd.) 11 010190429 FAITH GOSPEL MINISTRIES 12 010160008 Labour Organisation of Rural Development Society 13 147120555 Manav Seva Pratisthan 14 146940050 Durgapur Indira Pragati Society 15 147120648 Bibek Bikash Samaj Kalyan Kendra 16 105030040 Manaba Vikash Niyajana Samiti(Mani) 17 094421343 LIFE IN JESUS CHRIST PRAYER MISSION TRUST 18 083790017 Buldana Urban Charitable society 19 083990183 Network in Thane By People Living With HIV AIDS NTP Plus 20 094510004 St. Sebastian Church 21 052950008 Malabar Bible Fellowship 22 094590144 G S B Bankers Educational & Welfare Trust 23 136550424 GRAMIN SAMAJIK VIKAS SANSTHAN 24 104890156 MERRY WELFARE ORGANISATION 25 042080102 KARUNA FOUNDATION TRUST 26 285130053 Integrated Rural Development Through Education Centre 27 147040560 MOTHERCHAK NABODAY KISHALAY SANGHA 28 010310274 Navodaya Yuva Kendram 29 010140142 Nehru Yuvajana Seva Sangham 30 075850126 Womens Education & Awareness Development Trust 31 041910264 Hiran Charitable Trust 32 347880008 Himalayan Foundation 33 075920014 Rural Social Welfare Education and Emploument Development Trust 34 031170479 TAPAN 35 063160001 Satpura Integrated Rural Development Institute 36 125610003 Smt. -

Story of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS)

Story of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) by Walter K. Andersen and Shridhar D. Damle Reproduced by Sani H. Panhwar Story of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) by Walter K. Andersen and Shridhar D. Damle Reproduced by Sani H. Panhwar About the Book and Authors Hindu revivalism, a growing force in India, is rooted in the belief that Hinduism is endangered. This perception comes from many sources: the political assertiveness of minority groups like the Sikhs and Muslims, efforts to convert Hindus to other faiths, suspicions that the political authorities are "pandering" to minority groups, and the belief that "foreign" political and religious ideologies undermine community bonds. This book1 focuses on the best-organized and largest group committed to Hindu revivalism in India—the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (the RSS). Tracing the growth of the RSS since its formation in the mid-1920s, the authors examine its ideology and training system. They argue that the strength of the RSS lies in its ability to develop close bonds among its members and to sustain these links when members join the various RSS affiliate groups. The swayamsevaks (members) are the steel frame of the "family" of organizations around the RSS that work in the political arena, in social welfare, in the media, and among students, laborers, and Hindu religious groups. The symbiotic links between the RSS and the "family" are maintained by recruiting into the affiliates RSS members who have already demonstrated organizational skills. This superb training system is likely to serve the RSS well as it reaches out to a growing circle of individuals and groups buffeted by change and in search of a new community identity.