Story of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Secrets of RSS

Secrets of RSS DEMYSTIFYING THE SANGH (The Largest Indian NGO in the World) by Ratan Sharda © Ratan Sharda E-book of second edition released May, 2015 Ratan Sharda, Mumbai, India Email:[email protected]; [email protected] License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-soldor given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person,please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and didnot purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to yourfavorite ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hardwork of this author. About the Book Narendra Modi, the present Prime Minister of India, is a true blue RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or National Volunteers Organization) swayamsevak or volunteer. More importantly, he is a product of prachaarak system, a unique institution of RSS. More than his election campaigns, his conduct after becoming the Prime Minister really tells us how a responsible RSS worker and prachaarak responds to any responsibility he is entrusted with. His rise is also illustrative example of submission by author in this book that RSS has been able to design a system that can create ‘extraordinary achievers out of ordinary people’. When the first edition of Secrets of RSS was released, air was thick with motivated propaganda about ‘Saffron terror’ and RSS was the favourite whipping boy as the face of ‘Hindu fascism’. Now as the second edition is ready for release, environment has transformed radically. -

From Secular Democracy to Hindu Rashtra Gita Sahgal*

Feminist Dissent Hindutva Past and Present: From Secular Democracy to Hindu Rashtra Gita Sahgal* *Correspondence: secularspaces@ gmail.com Abstract This essay outlines the beginnings of Hindutva, a political movement aimed at establishing rule by the Hindu majority. It describes the origin myths of Aryan supremacy that Hindutva has developed, alongside the campaign to build a temple on the supposed birthplace of Ram, as well as the re-writing of history. These characteristics suggest that it is a far-right fundamentalist movement, in accordance with the definition of fundamentalism proposed by Feminist Dissent. Finally, it outlines Hindutva’s ‘re-imagining’ of Peer review: This article secularism and its violent campaigns against those it labels as ‘outsiders’ has been subject to a double blind peer review to its constructed imaginary of India. process Keywords: Hindutva, fundamentalism, secularism © Copyright: The Hindutva, the fundamentalist political movement of Hinduism, is also a Authors. This article is issued under the terms of foundational movement of the 20th century far right. Unlike its European the Creative Commons Attribution Non- contemporaries in Italy, Spain and Germany, which emerged in the post- Commercial Share Alike License, which permits first World War period and rapidly ascended to power, Hindutva struggled use and redistribution of the work provided that to gain mass acceptance and was held off by mass democratic movements. the original author and source are credited, the The anti-colonial struggle as well as Left, rationalist and feminist work is not used for commercial purposes and movements recognised its dangers and mobilised against it. Their support that any derivative works for anti-fascism abroad and their struggles against British imperialism and are made available under the same license terms. -

Architect of New India Fortnightly Magazine Editor Prabhat Jha

@Kamal.Sandesh KamalSandeshLive www.kamalsandesh.org kamal.sandesh @KamalSandesh SPECIAL EDITION 17 September, 2020 `100.00 ABHINANDAN ! Special Edition of Kamal Sandesh on the occasion of 70th birthday of Hon’ble Prime Minister SHRI NARENDRA MODI ARCHITECTARCHITECT OFOF NNEWEWArchitect ofII NewNDINDI India KAMAL SANDESHAA 1 Self-reliant India will stand on five Pillars. First Pillar is Economy, an economy that brings Quantum Jump rather than Incremental change. Second Pillar is Infrastructure, an infrastructure that became the identity of modern India. Third Pillar is Our System. A system that is driven by technology which can fulfill the dreams of the 21st century; a system not based on the policy of the past century. Fourth Pillar is Our Demography. Our Vibrant Demography is our strength in the world’s largest democracy, our source of energy for self-reliant India. The fifth pillar is Demand. The cycle of demand & supply chain in our economy is the strength that needs to be harnessed to its full potential. SHRI NARENDRA MODI Hon’ble Prime Minister of India 2 KAMAL SANDESH Architect of New India Fortnightly Magazine Editor Prabhat Jha Executive Editor Dr. Shiv Shakti Bakshi Associate Editors Ram Prasad Tripathy Vikash Anand Creative Editors Vikas Saini Bhola Roy Digital Media Rajeev Kumar Vipul Sharma Subscription & Circulation Satish Kumar E-mail [email protected] [email protected] Phone: 011-23381428, FAX: 011-23387887 Website: www.kamalsandesh.org 04 EDITORIAL 46 2016 - ‘IndIA IS NOT 70 YEARS OLD BUT THIS JOURNEY IS -

“Re-Rigging” the Vedas: Examining the Effects of Changing Education and Purity Standards and Political Influence on the Contemporary Hindu Priesthood

“Re-Rigging” the Vedas: Examining the Effects of Changing Education and Purity Standards and Political Influence on the Contemporary Hindu Priesthood Christine Shanaberger Religious Studies RST 490 David McMahan, advisor Submitted: May 4, 2006 Graduated: May 13, 2006 1 Introduction In the academic study of religion, we are often given impressions about a tradition that are textually accurate, but do not directly correspond with its practice amongst its devotees. Hinduism is one such tradition where scholarly work has been predominately textual and quite removed from practices “on the ground.” While most scholars recognize that many indigenous Hindu practices do not conform to the Brahmanical standards described in ancient Hindu texts, there has only recently been a movement to study the “popular,” non-Brahmanical traditions, let alone to look at the Brahmanical practice and its variance with ancient conventions. I have personally experienced this inconsistency between textual and popular Hinduism. After spending a semester in India, I quickly realized that my background in the study of Hinduism was, indeed, merely a background. I found myself re-learning aspects of the tradition and theology that I thought I had already understood and redefining the meaning of many practices as I learned of their practical application. Most importantly, I discovered that Hindu practices and beliefs are so diverse that I could never anticipate who would believe or practice in what way. I met many “modernized” Indians who both ignored and retained many orthodox elements of their traditions, priests who were unaware of even the most basic elements of Hindu mythology, and devotees who had no qualms engaging in both orthodox Brahmin and quite unorthodox non-Brahmin religious practices. -

Vivekananda Shila Smarak Ek Bharat Vijayi Bharat

Vivekananda Shila Smarak Ek Bharat Vijayi Bharat Vivekananda Kendra Gratefully Remembers and Invites the Hundreds and Thousands Who or Whose Families Had Contributed to the Building of The Grand Vivekananda Rock Memorial at Kanyakumari in 1970 To Celebrate the 50th Year of the Memorial [1970-2020] And Renew the Association Swami Vivekananda on the last bit of Indian Rock “Sitting on the last bit of Indian rock—I hit upon a plan: Suppose some disinterested sannyasins, bent on doing good to others, go from village to village, disseminating education and seeking in various ways to better the condition of all, down to the last person—can’t that bring forth good in time?” “We, as a nation, have lost our individuality, and that is the cause of all mischief in India. We have to give back to the nation its lost individuality and raise the masses.” (In a letter written to Swami Ramakrishnananda on 19 March 1894) Swami Vivekananda’s mission for rejuvenation of Bharat began with the plan he had hit upon when he sat on “the last bit of Indian rock”. Now, thanks to the invaluable contribution from all of you, a beautiful memorial - to recall Swami Vivekananda beginning his mission for India - now stands on that last bit of rock. The Memorial, built by a truly national effort put together by the monumental work of Sri Eknath Ranade; the man behind the mighty work, was dedicated to the nation in September 1970. 3 As Swami Vivekananda had his inspiration from the rock, Eknath Ranade took inspiration from the memorial built on the rock to found the Vivekananda Kendra which has now grown into a mighty spiritually oriented service mission manned by thousands of karyakartas. -

Academic Course Prospectus for the Session 2012-13

PROSPECTUS 2012-13 With Application Form for Admission Secondary and Senior Secondary Courses fo|k/kue~loZ/kuaiz/kkue~ NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF OPEN SCHOOLING (An autonomous organisation under MHRD, Govt. of India) A-24-25, Institutional Area, Sector-62, NOIDA-201309 Website: www.nios.ac.in Learner Support Centre Toll Free No.: 1800 180 9393, E-mail: [email protected] NIOS: The Largest Open Schooling System in the World and an Examination Board of Government of India at par with CBSE/CISCE Reasons to Make National Institute of Open Schooling Your Choice 1. Freedom To Learn With a motto to 'reach out and reach all', NIOS follows the principle of freedom to learn i.e., what to learn, when to learn, how to learn and when to appear in the examination is decided by you. There is no restriction of time, place and pace of learning. 2. Flexibility The NIOS provides flexibility with respect to : • Choice of Subjects: You can choose subjects of your choice from the given list keeping in view the passing criteria. • Admission: You can take admission Online under various streams or through Study Centres at Secondary and Senior Secondary levels. • Examination: Public Examinations are held twice a year. Nine examination chances are offered in five years. You can take any examination during this period when you are well prepared and avail the facility of credit accumulation also. • On Demand Examination: You can also appear in the On-Demand Examination (ODES) of NIOS at Secondary and Senior Secondary levels at the Headquarter at NOIDA and All Regional Centres as and when you are ready for the examination after first public examination. -

Misplaced Outrage Over Decision to Halt GM Crop Trials

Misplaced outrage over decision to halt GM crop trials 31 August 2014 | Views | By Narayanan Suresh Misplaced outrage over decision to halt GM crop trials The reported assurance of Environment Minister, Mr Prakash Javadekar, to anti-GM activitists who called on him to keep in abeyance the regulatory approval for the field trials of 15 crops, has predictably created a storm across the country. The mainstream media has accused the Narendra Modi government of pandering to the whims of organizations like the Swadesi Jagaran Manch (SJM) and Bharatiya Kisan Sangh (BKS) in preventing cultivation of new genetically modified (GM) crops in the country. Both these organizations are loose affiliates of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) which is the dominant constituent of the ruling NDA coalition. But most of these die-hard opponents of the government decision, to put on hold the regulatory approval taken by the Genetic Engineering Approval Committee (GEAC) on July 18, 2014, are missing the point. The Modi government would have actually betrayed the trust of the people if it allowed introduction of new GM crops. For the BJP manifesto in 2014 had clearly stated that "GM foods will not be allowed without full scientific evaluation of their long-term impact on soil production and biological impact on consumers." Obviously, the manifesto had taken inputs from various affiliated organizations and so the party could not have gone against its stated policy after assuming power. Of the 15 approvals for confined trials granted by GEAC, four are food crops -- mustard, brinjal, rice and chickpea. And the GEAC has also allowed the import of GM soybean oil by three MNCs -- Monsanto, Bayer BioScience and BASF. -

Rahul Sagar, Hindu Nationalists and the Cold

Chapter Ten Hindu Nationalists and the Cold War Rahul Sagar It is generally accepted that during the Cold War divergences between “hope and reality” rendered India and America “estranged democracies.”1 Te pre- cise nature of the Indo- American relationship during these decades remains a subject of fruitful study. For instance, Rudra Chaudhuri has argued that the Cold War’s many crises actually prompted India and the United States to “forge” a more nuanced relationship than scholars have realized.2 Tis chapter does not join this discussion. It examines a diferent side of the story. Rather than study the workings of the Congress Party–afliated political and bureaucratic elite in power during the Cold War, it focuses on the principal Opposition—the ideas and policies of the Hindu Mahasabha, the Jan Sangh, and the Bharatiya Janata Party (bJP), which have championed the cause of Hindu nationalism. Te Cold War–era policies of these parties have not been studied carefully thus far. A common assumption is that these parties had little to say about international afairs or that, to the extent that they had something to say, their outlook was resolutely militant. Tis chapter corrects this misperception. It shows that these parties’ policies alternated between being attracted to and being repulsed by the West. Distaste for communism and commitment to democracy drove them to seek friendship with the West, while resentment at U.S. eforts to contain India as well as fears about ma- terialism and Westernization prompted them to demand that the West be kept at a safe distance. 229 false sTarTs Surprisingly little has been written about the diversity of Indian views on international relations in the Cold War era. -

May 23, 2005 Annual Transfer Office Memorandum No

High Court Of Judicature At Allahabad OFFICE MEMORANDUM No.132/DR(S)/2005 Dated: Allahabad : May 23, 2005 The following Judge Small Causes Courts/ Additional Judge Small Causes Courts/ Civil Judge (Senior Division)/ Additional Civil Judge (Senior Division)/ Chief Judicial Magistrate/Additional Chief Judicial Magistrate/ Additional Chief Judicial Magistrate (Railway)/ Chief Metropolitan Magistrate/Additional Chief Metropolitan Magistrate have been transferred to the places in- dicated against their names below. They shall keep themselves ready to hand-over charge at their present place of posting on June 06, 2005 afternoon. The notification regarding their inter-se posting at the station to which they have been trans- ferred will follow. Sl Id Name of Present Place Place to which No No Officer of Posting transferred 1 5290 PRAVEEN KUMAR Agra Jhansi 2 5340 RAJIV SHARMA Agra Muzaffar Nagar 3 5675 SURENDRA SINGH Agra Bareilly 4 5434 ANOOP KUMAR GOEL Aligarh Barabanki 5 5439 NALIN KUMAR SRIVASTAVA Aligarh Fatehpur 6 5688 ALOK KUMAR PARASAR Aligarh Chitrakoot 7 5745 MOHD. IBRAHIM Aligarh Jhansi 8 5749 MUKESH KUMAR SINGHAL Aligarh Bijnor 9 5687 SATYA PRAKASH TRIPATHI Ambedkar N. at Akbarpur Lucknow 10 5298 AMAR NATH SINGH Auraiya Raebareli 11 5460 ASHOK KUMAR-VI Auraiya Gonda 12 5314 DINESH CHANDRA TRIPATHI Azamgarh Chitrakoot 13 5408 RAMESH CHANDRA-V Azamgarh Nagina-Bijnor 14 5229 SATISH KUMAR KAIN Bahraich Bijnor 15 5307 RAM ADHAR Balrampur Varanasi 16 5627 VIKASH SAXENA-II Banda Agra 17 5312 SHANTI PRAKASH ARVIND Barabanki Agra 18 5409 SANT -

Profile of Chaman Lal Gadoo

PROFILE OF CHAMAN LAL GADOO (AUTHOR AND SOCIAL ACTIVIST) VIDYA GAURI GADOO RESEARCH CENTRE S-71, Sunder Block, Shakarpur, Delhi—110092, Mob.9891297912, Email: [email protected] , Blog: www.clgadoo.blogspot.com Chaman Lal Gadoo with Swami Ramdev 1 PROFILE IN PICTURES C.L.Gadoo, President Smt. PRATIBHA PATIL & President Sh. K.R.NARAYANAN C.L.Gadoo with PM Sh.A.B.Vajpayee, & Sh. Madan Lal Khurana, BJP Delhi chief C.L.Gadoo with Dy. PM Sh.L.K.Advani & with Sh.L.K.Advani and Sh.K.N Sahani, 2 SWAMI SRI SRI RAVISHANKAR RELEASING BOOK KASHMIR HINDU SHRINES SWAMI RAMDEV RELEASING THE BOOK—KASHMIR HINDU SHRINES Author with Swami Girijeshananda(Jammu)Author with Acharya Balkrishna(Haridwar) 3 CL.Gadoo with PM Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru & with PM Sh.P.V.Narasimha Rao C.L. Gadoo, Sh. A.B.Vajpayee, Sh.S.L.Shakdhar, Dr.Hari Ohm, Dr. M. K.Teng c.l.gadoo,Sh.M.L.Khurana,Sh.B.S.Shekhawat,Sh.S.L.Shakdhar,Sh.KeshoBhaiPatel 4 BRIEF PROFILE Chaman Lal Gadoo, born in the year 1937 at Srinagar, Kashmir has been ardent Hindu nationalist from an early age. His father Pandit Janki Nath Gadoo, a teacher by profession, was a highly learned Kashmiri Pandit and his Mother Smt. Ragniya Gadoo, was a noble house wife, with a spiritual and religious discipline, and social bonding. She left for heavenly abode, at an early age. His Wife Smt. Vidya Gauri Gadoo was organizing & training commissioner, Bharat Scouts and Guides, Delhi State. Chaman Lal completed his early education at Srinagar and received technical education in Electronics Engineering and Industrial management at Delhi. -

Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya

Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya Who is Deendayal Upadhyaya? \n\n \n Deendayal Upadhyaya was born in a poor family in Nagla Chandrabhaan village near Mathura, UP, on 25 September, 1916. \n As a child, Deendayal had to face the profound grief of several deaths in the family. Deendayal moved from place to place and completed his masters degree. He was introduced to RSS and became a full timer in the late 1930s. \n Deendayal was a prolific writer and a successful editor. He wrote a number of books including Samrat Chandragupt and Jagatguru Shankaracharya, and an analysis of the Five Year plans in India. \n He was deputed to work in the Jana Sangh by Shri Golwalkar when the party was founded in 1951 by Dr Syama Prasad Mukherjee. From then till 1967 he remained the Jana Sangh All India General Secretary. \n It was during this time that he propounded the political philosophy of Integral Humanism. It is now 50 years since the Jana Sangh adopted Integral Humanism as its political-economic manifesto. \n Deendayal Upadhyaya died on February 11, 1968 under mysterious circumstances at the age 52. The murder of Pandit Deendayal still remains unresolved. \n \n\n What are some of his ideals? \n\n \n The concept of Integral Humanism he propounded envisages remedies for the post-globalisation maladies of the world. \n Upadhyaya conceived a classless, casteless and conflict-free social order. He stressed on the ancient Indian wisdom of oneness of the human kind. \n For him, the brotherhood of a shared, common heritage was central to political activism. -

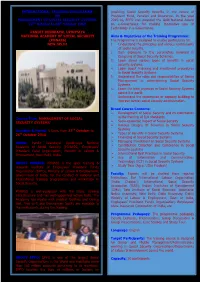

International Training Programme on Management

INTERNATIONAL TRAINING PROGRAMME providing Social Security benefits in the nature of ON Provident Fund, Pension and Insurance. In the year MANAGEMENT OF SOCIAL SECURITY SYSTEMS 2015-16, EPFO was awarded the Gold National Award 22nd October to 26th October 2018 on e-Governance for making Innovative use of Technology in e-Governance. PANDIT DEENDAYAL UPDHYAYA NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SOCIAL SECURITY Aims & Objectives of the Training Programme: (PDNASS) The Programme is designed to enable participants to: NEW DELHI 1. Understand the principles and various components of social security. 2. Gain exposure to the parameters involved in designing of Social Security Schemes. 3. Learn about various types of benefits in social security systems. 4. Learn about financing and investment procedures in Social Security Systems. 5. Understand the roles and responsibilities of Senior Management in administering Social Security Systems. 6. Learn the best practices in Social Security Systems across the world. 7. Understand the importance of capacity building to improve overall social security administration. Broad Course Contents: Development of Social Security and its culmination Course Title: „MANAGEMENT OF SOCIAL in the framing of ILO standards SECURITY SYSTEMS’ Socio-economic impact of Social Security Various Designs of Schemes in Social Security Duration & Period: 5 Days, from 22nd October to Systems 26th October 2018 Types of Benefits in Social Security Systems Financing of Social Security Systems Venue: Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya National Managing