Authoritarianism and Resistance in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Secrets of RSS

Secrets of RSS DEMYSTIFYING THE SANGH (The Largest Indian NGO in the World) by Ratan Sharda © Ratan Sharda E-book of second edition released May, 2015 Ratan Sharda, Mumbai, India Email:[email protected]; [email protected] License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-soldor given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person,please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and didnot purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to yourfavorite ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hardwork of this author. About the Book Narendra Modi, the present Prime Minister of India, is a true blue RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or National Volunteers Organization) swayamsevak or volunteer. More importantly, he is a product of prachaarak system, a unique institution of RSS. More than his election campaigns, his conduct after becoming the Prime Minister really tells us how a responsible RSS worker and prachaarak responds to any responsibility he is entrusted with. His rise is also illustrative example of submission by author in this book that RSS has been able to design a system that can create ‘extraordinary achievers out of ordinary people’. When the first edition of Secrets of RSS was released, air was thick with motivated propaganda about ‘Saffron terror’ and RSS was the favourite whipping boy as the face of ‘Hindu fascism’. Now as the second edition is ready for release, environment has transformed radically. -

Online Supplement Part I: Individual-Level Analysis

ONLINE SUPPLEMENT PART I: INDIVIDUAL-LEVEL ANALYSIS SECTION 1: DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS AND SUBSTANTIVE EFFECTS TABLE S.1: DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS FOR VOTER ANALYSIS (UPPER CASTE SAMPLE) TABLE S.2: DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS FOR VOTER ANALYSIS (DALIT AND ADIVASI SAMPLE) TABLE S.3: VARIABLES USED IN VOTER-LEVEL ANALYSIS TABLE S.4: SHIFTS IN SIMULATED PROBABILITY OF BJP SUPPORT AMONG DALITS AND ADIVASIS (ESTIMATED FROM MODELS REPORTED IN TABLE 1) TABLE S.5: SHIFTS IN SIMULATED PROBABILITY OF SUPPORTING BJP AMONG UPPER CASTES (ESTIMATED FROM MODELS REPORTED IN TABLE 1) SECTION 2: BASIC ROBUSTNESS CHECKS TABLE S.6: NO COLLINEARITY BETWEEN EXPLANATORY VARIABLES IN INDIVIDUAL- LEVEL SAMPLES FIGURE S1: ACCOUNTING FOR INFLUENTIAL OBSERVATIONS TABLE S.7: RESULTS AMONG NON-ELITES ARE ROBUST TO EXCLUDING HIGH INFLUENCE OBSERVATIONS TABLE S.8: RESULTS AMONG ELITES ARE ROBUST TO EXCLUDING HIGH INFLUENCE OBSERVATIONS (UPPER CASTE SAMPLE) TABLE S.9: MEMBERSHIP EFFECTS ARE ROBUST TO SEPARATELY CONTROLLING FOR INDIVIDUAL POTENTIAL CONFOUNDERS (NON-ELITES) TABLE S.10: RESULTS ARE ROBUST REMAIN TO SEPARATELY CONTROLLING FOR INDIVIDUAL POTENTIAL CONFOUNDERS (ELITES) TABLE S.11: RESULTS ARE NOT AFFECTED BY CONTROLLING FOR ADDITIONAL POLICY MEASURE: (BJP OPPOSITION TO CASTE-BASED RESERVATIONS) TABLE S.12: RESULTS ARE NOT AFFECTED BY INCLUDING ADDITIONAL IDEOLOGICAL POLICY MEASURE: (SUPPORT FOR BANNING RELIGIOUS CONVERSIONS) SECTION 3: CONTROLLING FOR VOTER OPINIONS OF POLITICAL PARTIES SECTION 3A: VIEWS OF BJP PERFORMANCE TABLE S.13A: RESULTS ARE ROBUST TO CONTROLLING FOR PERSONAL SATISFACTION WITH BJP-LED CENTRAL GOVERNMENT AND POCKETBOOK INCREASES DURING BJP TENURE (NON-ELITES) 1 TABLE S.13B: RESULTS ARE ROBUST TO CONTROLLING FOR PERSONAL SATISFACTION WITH BJP-LED CENTRAL GOVERNMENT AND POCKETBOOK INCREASES DURING BJP TENURE (ELITE SAMPLE) SECTION 3B: PARTY RATINGS: BJP VS. -

Introduction

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction The Invention of an Ethnic Nationalism he Hindu nationalist movement started to monopolize the front pages of Indian newspapers in the 1990s when the political T party that represented it in the political arena, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP—which translates roughly as Indian People’s Party), rose to power. From 2 seats in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian parliament, the BJP increased its tally to 88 in 1989, 120 in 1991, 161 in 1996—at which time it became the largest party in that assembly—and to 178 in 1998. At that point it was in a position to form a coalition government, an achievement it repeated after the 1999 mid-term elections. For the first time in Indian history, Hindu nationalism had managed to take over power. The BJP and its allies remained in office for five full years, until 2004. The general public discovered Hindu nationalism in operation over these years. But it had of course already been active in Indian politics and society for decades; in fact, this ism is one of the oldest ideological streams in India. It took concrete shape in the 1920s and even harks back to more nascent shapes in the nineteenth century. As a movement, too, Hindu nationalism is heir to a long tradition. Its main incarnation today, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS—or the National Volunteer Corps), was founded in 1925, soon after the first Indian communist party, and before the first Indian socialist party. -

Religious Movements, Militancy, and Conflict in South Asia Cases from India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan

a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religious Movements, Militancy, and Conflict in South Asia cases from india, pakistan, and afghanistan 1800 K Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 Authors E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org Joy Aoun Liora Danan Sadika Hameed Robert D. Lamb Kathryn Mixon Denise St. Peter July 2012 ISBN 978-0-89206-738-1 Ë|xHSKITCy067381zv*:+:!:+:! CHARTING our future a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religious Movements, Militancy, and Conflict in South Asia cases from india, pakistan, and afghanistan Authors Joy Aoun Liora Danan Sadika Hameed Robert D. Lamb Kathryn Mixon Denise St. Peter July 2012 CHARTING our future About CSIS—50th Anniversary Year For 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed practical solutions to the world’s greatest challenges. As we celebrate this milestone, CSIS scholars continue to provide strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a bipartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and de- velop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Since 1962, CSIS has been dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. After 50 years, CSIS has become one of the world’s pre- eminent international policy institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global development and economic integration. -

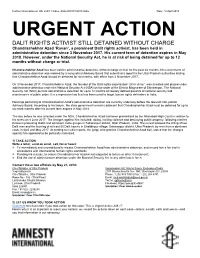

Missing Lawyer at Risk of Torture

Further information on UA: 248/17 Index: ASA 20/8191/2018 India Date: 10 April 2018 URGENT ACTION DALIT RIGHTS ACTIVIST STILL DETAINED WITHOUT CHARGE Chandrashekhar Azad ‘Ravan’, a prominent Dalit rights activist, has been held in administrative detention since 3 November 2017. His current term of detention expires in May 2018. However, under the National Security Act, he is at risk of being detained for up to 12 months without charge or trial. Chandrashekhar Azad has been held in administrative detention, without charge or trial, for the past six months. His current term of administrative detention was ordered by a non-judicial Advisory Board that submitted a report to the Uttar Pradesh authorities stating that Chandrashekhar Azad should be detained for six months, with effect from 2 November 2017. On 3 November 2017, Chandrashekhar Azad, the founder of the Dalit rights organisation “Bhim Army”, was arrested and placed under administrative detention under the National Security Act (NSA) on the order of the District Magistrate of Saharanpur. The National Security Act (NSA) permits administrative detention for up to 12 months on loosely defined grounds of national security and maintenance of public order. It is a repressive law that has been used to target human rights defenders in India. Hearings pertaining to Chandrashekhar Azad’s administrative detention are currently underway before the relevant non-judicial Advisory Board. According to his lawyer, the state government remains adamant that Chandrashekhar Azad must be detained for up to six more months after his current term expires in May 2018. The day before he was arrested under the NSA, Chandrashekhar Azad had been granted bail by the Allahabad High Court in relation to his arrest on 8 June 2017. -

Western Uttar Pradesh: Caste Arithmetic Vs Nationalism

VERDICT 2019 Western Uttar Pradesh: Caste Arithmetic vs Nationalism SMITA GUPTA Samajwadi Party patron Mulayam Singh Yadav exchanges greetings with Bahujan Samaj Party supremo Mayawati during their joint election campaign rally in Mainpuri, on April 19, 2019. Photo: PTI In most of the 26 constituencies that went to the polls in the first three phases of the ongoing Lok Sabha elections in western Uttar Pradesh, it was a straight fight between the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) that currently holds all but three of the seats, and the opposition alliance of the Samajwadi Party, the Bahujan Samaj Party and the Rashtriya Lok Dal. The latter represents a formidable social combination of Yadavs, Dalits, Muslims and Jats. The sort of religious polarisation visible during the general elections of 2014 had receded, Smita Gupta, Senior Fellow, The Hindu Centre for Politics and Public Policy, New Delhi, discovered as she travelled through the region earlier this month, and bread and butter issues had surfaced—rural distress, delayed sugarcane dues, the loss of jobs and closure of small businesses following demonetisation, and the faulty implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST). The Modi wave had clearly vanished: however, BJP functionaries, while agreeing with this analysis, maintained that their party would have been out of the picture totally had Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his message of nationalism not been there. travelled through the western districts of Uttar Pradesh earlier this month, conversations, whether at district courts, mofussil tea stalls or village I chaupals1, all centred round the coming together of the Samajwadi Party (SP), the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) and the Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD). -

25 May 2018 Hon'ble Chairperson, Shri Justice HL

25 May 2018 Hon’ble Chairperson, Shri Justice H L Dattu National Human Rights Commission, Block –C, GPO Complex, INA New Delhi- 110023 Respected Hon’ble Chairperson, Subject: Continued arbitrary detention and harassment of Dalit rights activist, Chandrashekhar Azad Ravana The Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA) appeals the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) to urgently carry out an independent investigation into the continued detention of Dalit human rights defender, Chandrashekhar Azad Ravan, in Saharanpur, Uttar Pradesh State, to furnish the copy of the investigation report before the non-judicial tribunal established under the NSA, and to move the court to secure his release. Chandrashekhar is detained under the National Security Act (NSA) without charge or trial. FORUM-ASIA is informed that in May 2017, Dalit and Thakur communities were embroiled in caste - based riots instigated by the dominant Thakur caste in Saharanpur city of Uttar Pradesh. The riots resulted in one death, several injuries and a number of Dalit homes being burnt. Following the protests, 40 prominent activists and leaders of 'Bhim Army', a Dalit human rights organisation, were arrested but later granted bail. Chandrashekhar Azad Ravan, a young lawyer and co-founder of ‘Bhim Army’, was arrested on 8 June 2017 following a charge sheet filed by a Special Investigation Team (SIT) constituted to investigate the Saharanpur incident. He was framed with multiple charges under the Indian Penal Code 147 (punishment for rioting), 148 (rioting armed with deadly weapon) and 153A among others, for his alleged participation in the riots. Even though Chandrashekhar was not involved in the protests, and wasn't present during the riot, he was detained on 8 June. -

Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada

Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of... https://irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/country-information/rir/Pages/index.aspx?doc=4... Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada India: Treatment of Dalits by society and authorities; availability of state protection (2016- January 2020) 1. Overview According to sources, the term Dalit means "'broken'" or "'oppressed'" (Dalit Solidarity n.d.a; MRG n.d.; Navsarjan Trust n.d.a). Sources indicate that this group was formerly referred to as "'untouchables'" (Dalit Solidarity n.d.a; MRG n.d.; Navsarjan Trust n.d.a). They are referred to officially as "Scheduled Castes" (India 13 July 2006, 1; MRG n.d.; Navsarjan Trust n.d.a). The Indian National Commission for Scheduled Castes (NCSC) identified that Scheduled Castes are communities that "were suffering from extreme social, educational and economic backwardness arising out of [the] age-old practice of untouchability" (India 13 July 2006, 1). The Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) [1] indicates that the list of groups officially recognized as Scheduled Castes, which can be modified by the Parliament, varies from one state to another, and can even vary among districts within a state (CHRI 2018, 15). According to the 2011 Census of India [the most recent census (World Population Review [2019])], the Scheduled Castes represent 16.6 percent of the total Indian population, or 201,378,086 persons, of which 76.4 percent are in rural areas (India 2011). The census further indicates that the Scheduled Castes constitute 18.5 percent of the total rural population, and 12.6 percent of the total urban population in India (India 2011). -

'Ambedkar's Constitution': a Radical Phenomenon in Anti-Caste

Article CASTE: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion Vol. 2 No. 1 pp. 109–131 brandeis.edu/j-caste April 2021 ISSN 2639-4928 DOI: 10.26812/caste.v2i1.282 ‘Ambedkar’s Constitution’: A Radical Phenomenon in Anti-Caste Discourse? Anurag Bhaskar1 Abstract During the last few decades, India has witnessed two interesting phenomena. First, the Indian Constitution has started to be known as ‘Ambedkar’s Constitution’ in popular discourse. Second, the Dalits have been celebrating the Constitution. These two phenomena and the connection between them have been understudied in the anti-caste discourse. However, there are two generalised views on these aspects. One view is that Dalits practice a politics of restraint, and therefore show allegiance to the Constitution which was drafted by the Ambedkar-led Drafting Committee. The other view criticises the constitutional culture of Dalits and invokes Ambedkar’s rhetorical quote of burning the Constitution. This article critiques both these approaches and argues that none of these fully explores and reflects the phenomenon of constitutionalism by Dalits as an anti-caste social justice agenda. It studies the potential of the Indian Constitution and responds to the claim of Ambedkar burning the Constitution. I argue that Dalits showing ownership to the Constitution is directly linked to the anti-caste movement. I further argue that the popular appeal of the Constitution has been used by Dalits to revive Ambedkar’s legacy, reclaim their space and dignity in society, and mobilise radically against the backlash of the so-called upper castes. Keywords Ambedkar, Constitution, anti-caste movement, constitutionalism, Dalit Introduction Dr. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Joint Submission to the United Nations Human Rights Committee, Adoption of List of Issues

JOINT SUBMISSION TO THE UNITED NATIONS HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE, ADOPTION OF LIST OF ISSUES 126TH SESSION, (01 to 26 July 2019) JOINTLY SUBMITTED BY NATIONAL DALIT MOVEMENT FOR JUSTICE-NDMJ (NCDHR) AND INTERNATIONAL DALIT SOLIDARITY NETWORK-IDSN STATE PARTY: INDIA Introduction: National Dalit Movement for Justice (NDMJ)-NCDHR1 & International Dalit Solidarity Network (IDSN) provide the below information to the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Committee (the Committee) ahead of the adoption of the list of issues for the 126th session for the state party - INDIA. This submission sets out some of key concerns about violations of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (the Covenant) vis-à- vis the Constitution of India with regard to one of the most vulnerable communities i.e, Dalit's and Adivasis, officially termed as “Scheduled Castes” and “Scheduled Tribes”2. Prohibition of Traffic in Human Beings and Forced Labour: Article 8(3) ICCPR Multiple studies have found that Dalits in India have a significantly increased risk of ending in modern slavery including in forced and bonded labour and child labour. In Tamil Nadu, the majority of the textile and garment workforce is women and children. Almost 60% of the Sumangali workers3 belong to the so- called ‘Scheduled Castes’. Among them, women workers are about 65% mostly unskilled workers.4 There are 1 National Dalit Movement for Justice-NCDHR having its presence in 22 states of India is committed to the elimination of discrimination based on work and descent (caste) and work towards protection and promotion of human rights of Scheduled Castes (Dalits) and Scheduled Tribes (Adivasis) across India. -

The Saffron Wave Meets the Silent Revolution: Why the Poor Vote for Hindu Nationalism in India

THE SAFFRON WAVE MEETS THE SILENT REVOLUTION: WHY THE POOR VOTE FOR HINDU NATIONALISM IN INDIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Tariq Thachil August 2009 © 2009 Tariq Thachil THE SAFFRON WAVE MEETS THE SILENT REVOLUTION: WHY THE POOR VOTE FOR HINDU NATIONALISM IN INDIA Tariq Thachil, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 How do religious parties with historically elite support bases win the mass support required to succeed in democratic politics? This dissertation examines why the world’s largest such party, the upper-caste, Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has experienced variable success in wooing poor Hindu populations across India. Briefly, my research demonstrates that neither conventional clientelist techniques used by elite parties, nor strategies of ideological polarization favored by religious parties, explain the BJP’s pattern of success with poor Hindus. Instead the party has relied on the efforts of its ‘social service’ organizational affiliates in the broader Hindu nationalist movement. The dissertation articulates and tests several hypotheses about the efficacy of this organizational approach in forging party-voter linkages at the national, state, district, and individual level, employing a multi-level research design including a range of statistical and qualitative techniques of analysis. In doing so, the dissertation utilizes national and author-conducted local survey data, extensive interviews, and close observation of Hindu nationalist recruitment techniques collected over thirteen months of fieldwork. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Tariq Thachil was born in New Delhi, India. He received his bachelor’s degree in Economics from Stanford University in 2003.