The Eurasec Transport Corridors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asia Rail Bridge One Belt One Road – the New Silk Road ______

Asia Rail Bridge One Belt One Road – The New Silk Road ______________________________________________ What started over 2000 years ago is being revived today THE WORLD IS CHANGING HOW WE LIVE In times of global competition, all options must be considered, toHOW maintain WE WORK its position in the market. HOW WE MOVE The rapid growth of the NEW SILK ROAD NUMBER OF TRAINS FROM 2011 TO 2019 JULY 5000 4407 4500 4247 4013 4000 3500 3000 2500 2105 2000 1832 1500 1105 968 1000 500 195 0 2011 - 2015 2016 - 2017 2018 2019 WB EB Source: China Railway Corporation, National Development and Reform Commission China - One Belt One Road – The New Silk Road Southern Routing Northern Routing 17 – 19 days 18 – 20 days Manzhouli,China/Zabaikalsk,Russia Via Alashankou,China/Dostyk,Kazakhstan Erenhot,China/Zamyn-Uud, Mongolia Moscow Ekaterinburg Novosibirsk Hamburg Malaszewicze Minsk Chita Manzhouli Astana Duisburg Warsaw Haerbin Nuremberg Dostyk Munich Altynkol Erenhot Khorgos Shenyang Zhengzhou Tianjin Xian Chengdu Chongqing Suzhou Wuhan Yiwu Changsha TEN-T Network – Trans-European Transport Network The Trans-European transport project is a network of roads, railways, airports and water infrastructure in the North Europe European Union Central Europe East Europe South Europe Rail Service FCL Pick up Shanghai Door → Door 23 Days 2 days pre carriage Door Arrival Rail Station China CN 2 days cut off before ETD Cross border Alanshankou → Dostyk B B Cross border Brest → Malasevice Arrival Rail Station Europe HAM Door Delivery 2-3 days after ETA AVERAGE TRANSIT TIME 2017 – 2018 – 2019 25 22.1 20.4 20 19.3 18.1 17.7 16.8 16.8 15.6 15 10 5 0 T-T 2017 T-T 2018 T-T 2019 Last 4 weeks WB EB DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2025 1.000.000 1.000.000 TEU Over 1.000.000 Container will be moved in the year 2025 between China and Europe Reduction of the transit time Transit time under 10 days With Block chain technology, harmonized documents and regulations of customs rules. -

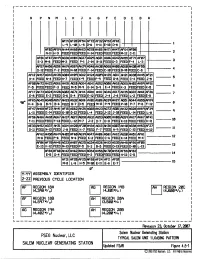

Salem Generating Station, Units 1 & 2, Revision 29 to Updated Final Safety Analysis Report, Chapter 4, Figures 4.5-1 to 4.5

r------------------------------------------- 1 I p M J B I R N L K H G F E D c A I I I I I Af'Jq AF20 AF54 AF72 32 AF52 AF18 I L-q L-10 L-15 D-6 -11 E-10 D-8 l I AF03 Af't;qAH44 AH60 AH63 AG70 AH65 AH7l AH47 AFS4 AF08 I N-ll H-3 FEED FEED FEED H-14 FEED FEED FEED M-12 C-11 2 I AF67 AH4q AH04 AG27 AG2<i' AG21 AG16 AG42 AF71 AF07 AF01 AG36 AH!5!5 3 I E-3 M-6 FEED M-3 FEED P-1 J-14 B-11 FEED D-3 FEED F-4 L-3 I AF67 AH5S AG56 Atflq AGsq AH2<1' AG48 AH30 AG68 AH08 AG60 AH30 AF55 I D-12 FEED F-2 FEED N-11 FEED F-14 FEED C-11 FEED B-11 FEED C-8 4 I AF12 AH57 AG43 AH38 AHtiJq AG12 AH24 AGfR AH25 AGil AG31 AH45 AF21 AGlM AH21 5 I H~4 FEED N-4 FEED H-7 FEED K~q FEED F-q FEED G-8 FEED C-4 FEED J-15 I AF50 AH72 AH22 AGS6 AH15 AGll.lAG64 AG41 AG52 AG88 AH18 AG65 AHIJ2 AH5q AF51 I F-5 FEED FEED F-3 FEED M-5 r+q G-14 o-q E-4 FEED K-3 FEED FEED K-5 6 I f:Fl7 AH73 AG24 AH28 AG82 AG71 AH14 AG18 AHil AG46 AG17 AH35 AG22 AH61 AF26 7 I E-8 FEED E-2 FEED G-6 G-4 FEED E-12 FEED J-4 J-6 FEED L-2 FEED E-5 I Af&q I qeo AF65 AG45 AtM0 AG57 AH33 AG32 AG16 AH01 AGI6 AG3<1' AH27 AG51 AG44 AG55 K-4 B-8 e-q B-6 FEED B-7 P-5 FEEC M-11 P-q FEED P-11 P-7 P-8 F-12 8 I AF47 AH68 AF23 AH41 AF1!5 AG62 AH26 AG03 AH23 AH32 AG28 AHsq AF3<1' q I L-U FEED E-14 FEED G-10 G-12 FEED L-4 FEED FEED L-14 FEED L-8 I ~~ AF66 AH66 AH10 AG67 AH37 AGJq AG68 AG3l AG63 AG05 AH08 AG5q AH17 AH67 AF41 I F-11 FEED FEED F-13 FEED L-12 M-7 J-2 D-7 D-11 FEED K-13 FEED FEED K-11 10 I AE33 AH!52 AG37 AH31 AG14 AH20 AF20 AH34 AG13 AH36 AG07 AH40 AG38 AH!53 AF27 I G-ll FEED N-12 FEED J-8 FEED K-7 FEED -

Economic and Social Council

UNITED NATIONS E Economic and Social Distr. GENERAL Council TRANS/SC.1/AC.5/2002/1 28 March 2002 Original: ENGLISH ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE INLAND TRANSPORT COMMITTEE Working Party on Road Transport Ad hoc Meeting on the Implementation of the AGR (Eighteenth session, 10-11 June 2002 agenda item 4) CONSIDERATION OF PROPOSALS FOR AMENDMENTS TO ANNEX 1 OF THE AGR Transmitted by Kazakhstan The Ministry of Transport and Communications of the Republic of Kazakhstan, having reviewed the text of the European Agreement on Main International Traffic Arteries (AGR) in the light of amendments 1-8 to the original text, and also the updated version of the map of the international E road network, wishes to make the following observations. Kazakhstan’s Blueprint for road traffic development outlines six main transit corridors: 1. Tashkent - Shymkent - Taraz - Bishkek - Almaty - Khorgos; 2. Shymkent - Kyzylorda - Aktyubinsk - Uralsk - Samara; 3. Almaty - Karagandy - Astana - Petropavlovsk; 4. Astrakhan - Atyrau - Aktau - Turkmen frontier; 5. Omsk - Pavlodar - Semipalatinsk - Maikapshagai; 6. Astana - Kostanay - Chelyabinsk. GE.02- TRANS/SC.1/AC.5/2002/1 page 2 Accordingly, the following amendments and additions are proposed to annex I to the AGR and the draft map of the international road network: 1. E 40. After Kharkov extend as follows: … Lugansk - Volgograd - Astrakhan - Atyrau - Beineu - Kungrad - Nukus - Bukhara - Nawoy - Samarkand - Dzhizak - Tashkent - Shymkent - Taraz - Bishkek - Almaty - Sary-Ozek - Taldykorgan - Usharal - Taskesken - Ayaguz - Georgievka - Ust-Kamenogorsk - Leninogorsk - Ust-Kan. The Leninogorsk - Ust-Kan section should be indicated on the map. 2. E 38 should be extended to Shymkent. The Kyzylorda - Shymkent section should be assigned a dual number (E 123/E 38). -

Policy & Governance Committee

AGENDA BOG Policy & Governance Committee Meeting Date: February 12, 2021 Location: Videoconference Chair: Kamron Graham Vice-Chair: Kate Denning Members: Gabriel Chase, Kate Denning, John Grant, Rob Milesnick, Curtis Peterson, Joe Piucci, David Rosen Staff Liaison: Helen M. Hierschbiel Charge: Develops and monitors the governing rules and policies relating to the structure and organization of the bar; ensures that all bar programs and services comply with organizational mandates and achieve desired outcomes. Identifies and brings emerging issues to the BOG for discussion and action. 2021 PGC Work Plan 1. Wellness Task Force Report. Review report and decide whether to pursue any Exhibit Action 10 recommendations. 2. Evidence-Based Decision-Making Policy. Review Futures Task Force recommendation regarding evidence-based decision-making To Be Posted Action 10 policy and consider whether to adopt the recommended policy. 3. HOD Authority. Discuss whether to pursue changes to limits of HOD authority either Exhibit Action 10 through amendments to HOD Rules or Bar Act. 4. OSB Bylaw Overhaul. Review draft of OSB bylaw overhaul, splitting between policies and Exhibit Discussion 20 bylaws. 5. Bar Sponsorship of Lawyer Referral Services. Review issue presented by Legal Ethics Exhibit Discussion 20 Committee. February 12, 2021 Policy & Governance Committee Agenda Page 2 6. Section Program Review. Review feedback Exhibit Discussion 20 regarding proposed changes to bylaws. 7. Approve minutes of January 8, 2021 meeting. Exhibit Action 1 2021 POLICY & GOVERNANCE WORK PLAN February 12, 2021 draft 2021 AREAS OF TO DO TASKS IN PROCESS (PGC) PGC TASKS DONE IN PROCESS (BOG) BOG TASKS FOCUS 1. Identify information needed 1. -

Water Resources Lifeblood of the Region

Water Resources Lifeblood of the Region 68 Central Asia Atlas of Natural Resources ater has long been the fundamental helped the region flourish; on the other, water, concern of Central Asia’s air, land, and biodiversity have been degraded. peoples. Few parts of the region are naturally water endowed, In this chapter, major river basins, inland seas, Wand it is unevenly distributed geographically. lakes, and reservoirs of Central Asia are presented. This scarcity has caused people to adapt in both The substantial economic and ecological benefits positive and negative ways. Vast power projects they provide are described, along with the threats and irrigation schemes have diverted most of facing them—and consequently the threats the water flow, transforming terrain, ecology, facing the economies and ecology of the country and even climate. On the one hand, powerful themselves—as a result of human activities. electrical grids and rich agricultural areas have The Amu Darya River in Karakalpakstan, Uzbekistan, with a canal (left) taking water to irrigate cotton fields.Upper right: Irrigation lifeline, Dostyk main canal in Makktaaral Rayon in South Kasakhstan Oblast, Kazakhstan. Lower right: The Charyn River in the Balkhash Lake basin, Kazakhstan. Water Resources 69 55°0'E 75°0'E 70 1:10 000 000 Central AsiaAtlas ofNaturalResources Major River Basins in Central Asia 200100 0 200 N Kilometers RUSSIAN FEDERATION 50°0'N Irty sh im 50°0'N Ish ASTANA N ura a b m Lake Zaisan E U r a KAZAKHSTAN l u s y r a S Lake Balkhash PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC Ili OF CHINA Chui Aral Sea National capital 1 International boundary S y r D a r Rivers and canals y a River basins Lake Caspian Sea BISHKEK Issyk-Kul Amu Darya UZBEKISTAN Balkhash-Alakol 40°0'N ryn KYRGYZ Na Ob-Irtysh TASHKENT REPUBLIC Syr Darya 40°0'N Ural 1 Chui-Talas AZERBAIJAN 2 Zarafshan TURKMENISTAN 2 Boundaries are not necessarily authoritative. -

Asia-Europe Connectivity Vision 2025

Asia–Europe Connectivity Vision 2025 Challenges and Opportunities The Asia–Europe Meeting (ASEM) enters into its third decade with commitments for a renewed and deepened engagement between Asia and Europe. After 20 years, and with tremendous global and regional changes behind it, there is a consensus that ASEM must bring out a new road map of Asia–Europe connectivity and cooperation. It is commonly understood that improved connectivity and increased cooperation between Europe and Asia require plans that are both sustainable and that can be upscaled. Asia–Europe Connectivity Vision 2025: Challenges and Opportunities, a joint work of ERIA and the Government of Mongolia for the 11th ASEM Summit 2016 in Ulaanbaatar, provides the ideas for an ASEM connectivity road map for the next decade which can give ASEM a unity of purpose comparable to, if not more advanced than, the integration and cooperation efforts in other regional groups. ASEM has the platform to create a connectivity blueprint for Asia and Europe. This ASEM Connectivity Vision Document provides the template for this blueprint. About ERIA The Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA) was established at the Third East Asia Summit (EAS) in Singapore on 21 November 2007. It is an international organisation providing research and policy support to the East Asia region, and the ASEAN and EAS summit process. The 16 member countries of EAS—Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Viet Nam, Australia, China, India, Japan, Republic of Korea, and New Zealand—are members of ERIA. Anita Prakash is the Director General of Policy Department at ERIA. -

CAREC Corridor Implementation Progress, Actions Planned and Support Needs

CAREC Corridor Implementation Progress, Actions Planned and Support Needs Republic of Kazakhstan Ministry for Investment and Development CONSTRUCTION AND RECONSTRUCTION OF ROADS UNDER NURLY ZHOL Results for 2017 Budget- 316.4 billion tenges Plans for 2018 Length covered – 4.4 thousand km Budget – 269.4 billion tenges Completed– 602 km, including Length covered by works – 4,2 thousand km Center –South – 16 km, Aktau-Schetpe – 170 км, Aktau-Beineu – 60 km; Center – East – 216 km, Almaty-Taldykorgan - 24, Completed – 528 km, including Aktobe-Makat – 26 km, Uralsk-Kamenka– 65 km, Astana-Petropavlovsk – 5 km, Kordai bypass road – 21 km; 1 CONSTRUCTION AND RECONSTRUCTION OF ROADS IN 2018 Budget – 269.4 billion tenges; 1, Temirtau-Karaganda–61 km Length covered by works – 4.2 thousand km; Including Kargandabypass, toll road Completed – 528 km. Cost – 64 billion tenges, Budget 2018 – 13,8 billion tenges. Implementation period: 2017-2020 2. South-West Astana bypass road – 33 km Cost – 60.2 billion tenges. Budget 2018 – 26,8 billion tenges. Implementation period: 2017-2019 3. Astana-Pavlodar-Semei – Kalbatau – 914 km Cost – 305 billion tenges. Budget 2018 – 48 billion tenges, Implementation period: 2010-2019 4. Astana-Petropavlovsk-RF border – 61 km Including access road to Kokshetau Cost – 44,2 billion tenges. Budget 2018 – 12,9 billion tenges, Completed в 2019 5. Щучинск-Зеренда – 80 km Cost – 15,2 billion tenges, Budget 2018 – 3,3 billion tenges. Implementation period: 2017-2019 6. Kostanai-Denisovka – 114 km Cost – 36,2 billion tenges. Budget 2018 - 3,5 billion tenges. Implementation period: 2017-2020 7. Aktobe-Makat – 458 km Cost – 178,9 billion tenges ( Budget 2018 - 51,3 billion tenges,. -

Dating of Remains of Neanderthals and Homo Sapiens from Anatolian Region by ESR-US Combined Methods: Preliminary Results

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 5, ISSUE 05, MAY 2016 ISSN 2277-8616 Dating Of Remains Of Neanderthals And Homo Sapiens From Anatolian Region By ESR-US Combined Methods: Preliminary Results Samer Farkh, Abdallah Zaiour, Ahmad Chamseddine, Zeinab Matar, Samir Farkh, Jamal Charara, Ghayas Lakis, Bilal Houshaymi, Alaa Hamze, Sabine Azoury Abstract: We tried in the present study to apply the electron spin resonance method (ESR) combined with uranium-series method (US), for dating fossilized human teeth and found valuable archaeological sites such as Karain Cave in Anatolia. Karain Cave is a crucial site in a region that has yielded remains of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, our direct ancestors. The dating of these remains allowed us to trace the history, since the presence of man on earth. Indeed, Anatolia in Turkey is an important region of the world because it represents a passage between Africa, the Middle East and Europe. Our study was conducted on faunal teeth found near human remains. The combination of ESR and US data on the teeth provides an understanding of their complex geochemical evolution and get better estimated results. Our samples were taken from the central cutting where geological layers are divided into archaeological horizons each 10 cm. The AH4 horizon of I.3 layer, which represents the boundary between the Middle Paleolithic and Upper Paleolithic, is dated to 29 ± 4 ka by the ESR-US model. Below, two horizons AH6 and AH8 in the same layer I.4 are dated respectively 40 ± 6 and 45 ± 7 ka using the ESR-US model. -

Pin Information for the Intel® Stratix®10 1SG10M Device Version: 2020-10-22

Pin Information for the Intel® Stratix®10 1SG10M Device Version: 2020-10-22 TYPE BANK NF74 Package Transceiver I/O 1CU10 28 Transceiver I/O 1CU20 28 Transceiver I/O 1DU10 12 Transceiver I/O 1DU20 12 Transceiver I/O 1EU10 20 Transceiver I/O 1EU20 20 Transceiver I/O 1KU12 28 Transceiver I/O 1KU22 28 Transceiver I/O 1LU12 12 Transceiver I/O 1LU22 12 Transceiver I/O 1MU12 20 Transceiver I/O 1MU22 20 LVDS I/O 2AU1 48 LVDS I/O 2AU2 48 LVDS I/O 2BU1 48 LVDS I/O 2BU2 48 LVDS I/O 2CU1 48 LVDS I/O 2CU2 48 LVDS I/O 2FU1 48 LVDS I/O 2FU2 48 LVDS I/O 2GU1 48 LVDS I/O 2GU2 48 LVDS I/O 2HU1 48 LVDS I/O 2HU2 48 LVDS I/O 2IU1 48 LVDS I/O 2IU2 48 LVDS I/O 2JU1 48 LVDS I/O 2JU2 48 LVDS I/O 2KU1 48 LVDS I/O 2KU2 48 LVDS I/O 2LU1 48 LVDS I/O 2LU2 48 LVDS I/O 2MU1 48 LVDS I/O 2MU2 48 LVDS I/O 2NU1 48 LVDS I/O 2NU2 48 LVDS I/O 3AU1 48 LVDS I/O 3AU2 48 LVDS I/O 3BU1 48 LVDS I/O 3BU2 48 LVDS I/O 3CU1 48 LVDS I/O 3CU2 48 LVDS I/O 3DU1 48 LVDS I/O 3DU2 48 LVDS I/O 3EU1 48 LVDS I/O 3EU2 48 LVDS I/O 3FU1 48 PT- 1SG10M Copyright © 2020 Intel Corp IO Resource Count Page 1 of 49 Pin Information for the Intel® Stratix®10 1SG10M Device Version: 2020-10-22 TYPE BANK NF74 Package LVDS I/O 3FU2 48 LVDS I/O 3GU1 48 LVDS I/O 3GU2 48 LVDS I/O 3HU1 48 LVDS I/O 3HU2 48 LVDS I/O 3IU1 48 LVDS I/O 3IU2 48 LVDS I/O 3JU1 48 LVDS I/O 3JU2 48 LVDS I/O 3KU1 48 LVDS I/O 3KU2 48 LVDS I/O 3LU1 48 LVDS I/O 3LU2 48 SDM shared LVDS I/O SDM_U1 29 SDM shared LVDS I/O SDM_U2 29 3V I/O U10 8 3V I/O U12 8 3V I/O U20 8 3V I/O U22 8 i. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized ’ Report No: 5 1477-Kz PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED LOAN Public Disclosure Authorized IN THE AMOUNT OF US$198.5 MILLION TO THE KAZAKHSTAN ELECTRICITY GRID OPERATING COMPANY WITH THE GUARANTEE OF THE REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN Public Disclosure Authorized FOR AN ALMA ELECTRICITY TRANSMISSION PROJECT November 17,2009 Sustainable Development Department Central Asia Country Unit Europe and Central Asia Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective October 29, 2009) Currency Unit = Kazakh Tenge (KZT), 1 KZT = 100 tyin KZT 1.0 = US$0.0066 US$l.O = KZT 150.71 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 3 1 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ARNM Agency for Regulation of Natural Monopolies kV Kilovolt (1,000 Volts) CAPS Central Asian Power System kWh Kilowatt Hour (1,000 Watt Hours);; DA Designated Account LA Loan Agreement DBK Development Bank of Kazakhstan LAP Land Acquisition Plan DP Development Plan LAPF Land Acquisition Policy Framework EA Environmental Assessment MES Regional Branch of KEGOC EBRD European Bank for Reconstruction and Development MHPP Moinak Hydroelectric Power Plant EIRR Economic Internal Rate of Return MVA Megavolt Ampere (1,000 KVA) EMP Environmental Management Plan MWh Megawatt Hour (1,000 kWh) ESO Energy Supply Organization -

Athens County Communities

51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 C GM JOHNSON C GM JOHNSON D HILL-BUCHTEL RD y R ODNR RD Sunda 33 W L O CARBON L A L U D O E H R A E B A K OLD A AR 278 DU SW O WATERWORKS HILL RD M C RD A P N K S RD BUCHTEL T-624A R D 13 T-622 D HOCKING COUNTY D KL 78 R Creek N A EY T N 31 E D O DR S T-35 O W HOCKING COUNTY R T N ILLIAMS ST ATHENS COUNTY W S H S U O Y J RD GLOUSTER CEMETERY O Sunday ATHENS COUNTY C J DEW T BUCHTEL UNITED H A 5 O EDWARDS ST CEMETERY S CEMETERY T-315 M 7 H K METHODIST CHURCH R 6 A O M C N I K D R W R R D E E M Y R AMO N D E O E I I CONNER M D o W D W E L E V n N P ST S O T-567 FRANK ST R T BESSEMER RDELM ST S L F d A B L ELM T B S A N T B T RD R K a W LOVE T T O A S y M V r E A S V ANKLI T R N T-675 I F S a 78 Y T-22 A T-1276 T SYCAMORE ST A R O A PINE ST EA T-1276 R n O D T L IETTA c L GROVER DOVER T P 685 h A WHITMORE T-22 S K GROVER ST T Nelsonville LID E AV EUC A D D FAIRVIEWSCOS V GROVE DR ST VERITY ST FR-3 u A V R D - York n COLLEGE ST RD L A O P E d E N I R DOVER VILLAGE OF GLOUSTER a G N CROSS ST y S R E E DR BUCHTEL MOUND R LAN Nelsonville - York H Buchtel MAYOR’S C R W O O D Park DIAMOND O AV r ST U V E Nelsonville Community OFFICE IO E E H T N Park C O D Y 33B BRICK RD R T-22A S R E C W ST D T K TWELFTH ST DR ST BUCK E E S YE WATERLOO r C B BUCHTEL e A D APARTMENTS N EARL ST OAK ST OAK MILL ST Wayne National Forest TRIMBLSYLVANIAE AV BROAD T-1305 U K PINE GROVE PINE H C e C ELIZABETH MT ST MARY DR B ST MARY OF RD T EMBRY ST GLOUSTER FORT ST FORT k ADAMS -

1St IRF Asia Regional Congress & Exhibition

1st IRF Asia Regional Congress & Exhibition Bali, Indonesia November 17–19 , 2014 For Professionals. By Professionals. "Building the Trans-Asia Highway" Bali’s Mandara toll road Executive Summary International Road Federation Better Roads. Better World. 1 International Road Federation | Washington, D.C. ogether with the Ministry of Public Works Indonesia, we chose the theme “Building the Trans-Asia Highway” to bring new emphasis to a visionary project Tthat traces its roots back to 1959. This Congress brought the region’s stakeholders together to identify new and innovative resources to bridge the current financing gap, while also sharing case studies, best practices and new technologies that can all contribute to making the Trans-Asia Highway a reality. This Congress was a direct result of the IRF’s strategic vision to become the world’s leading industry knowledge platform to help countries everywhere progress towards safer, cleaner, more resilient and better connected transportation systems. The Congress was also a reflection of Indonesia’s rising global stature. Already the largest economy in Southeast Asia, Indonesia aims to be one of world’s leading economies, an achievement that will require the continued development of not just its own transportation network, but also that of its neighbors. Thank you for joining us in Bali for this landmark regional event. H.E. Eng. Abdullah A. Al-Mogbel IRF Chairman Minister of Transport, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Indonesia Hosts the Region’s Premier Transportation Meeting Indonesia was the proud host to the 1st IRF Asia Regional Congress & Exhibition, a regional gathering of more than 700 transportation professionals from 52 countries — including Ministers, senior national and local government officials, academics, civil society organizations and industry leaders.