Congolese Refugee Students in Higher Education: Equity And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regno Del Congo 1 Regno Del Congo

Regno del Congo 1 Regno del Congo Kongo Descrizione generale Nome completo: Regno del Kongo Nome ufficiale: Kongo dya Ntotila Lingua ufficiale: bantu, kikongo Capitale: M'banza-Kongo Forma politica Forma di stato: Reame Nascita: 1395 con Lukeni lua Nimi Fine: 1914 con Manuel III del Congo Territorio e popolazione Bacino geografico: Africa Massima estensione: 129,400 km² nel 1650 Popolazione: 509.250 nel 1650 Economia Moneta: Raffia Religione e Società Religioni preminenti: Cristianesimo Evoluzione storica Preceduto da: Succeduto da: Angola portoghese Regno del Congo 2 Il Regno del Congo (o Impero del Congo, Kongo dya Ntotila o Wene wa Kongo in kikongo) fu un regno dell'Africa Occidentale nel periodo fra il XIV secolo (circa 1395) e l'inizio del XX secolo (1914). Il territorio dell'impero includeva l'attuale Angola settentrionale (inclusa l'enclave della Provincia di Cabinda), la Repubblica del Congo, e la parte occidentale della Repubblica Democratica del Congo. Nel periodo della sua massima potenza, controllava un territorio che si estendeva dall'Oceano Atlantico a ovest fino al fiume Kwango a est, e dal fiume Congo a nord fino al fiume Kwanza a sud. Il regno comprendeva numerose province, e godeva del rapporto di vassallaggio di molti regni circostanti, come quelli di N'goyo, Kakongo, Ndongo e Matamba. Il monarca dell'impero era chiamato Manikongo.[1] L'etnia principale del regno era quella dei Bakongo o Essikongo, appartenente al più grande gruppo etnolinguistico dei Bantu. Storia Fonti Gran parte di quanto si ipotizza sulla storia antica del Regno del Congo (precedente all'inizio dei rapporti con i portoghesi) deriva dalla tradizione orale locale, trascritta dagli Europei per la prima volta nel tardo XVI secolo. -

Conversion to Christianity in African History Before Colonial Modernity: Power, Intermediaries and Texts

Conversion to Christianity in African History before Colonial Modernity: Power, Intermediaries and Texts Kirsten Ru.. ther∗ This article examines different paradigms of conversions to Christianity in regions of Africa prior to the advent of colonial modernity. Religious change, in general, connected converts and various intermediaries to re- sources and power within specific settings. Even though African cultures were oral, conversions generated the production of texts which became important print media and were at least partly responsible for prompting conversions elsewhere in the world. The first case study explains how mission initiatives along the so-called West African slave coast almost always resulted in failure between 1450 and 1850, but how these failed efforts figure as important halfway options which reveal fundamental mechanisms of conversion. The dynamics of interaction were different in the African Kingdom of Kongo, where conversions became intimately entwined in the consolidation of political power and where, subsequent to the adoption of Christianity, new understandings of power evolved. Last but not least, in South Africa, again, another paradigm of conversion de- veloped within the nexus of conflict and settler violence. Contested nar- ratives of Christianity and conversion emerged as settlers tried to keep Christianity as a religious resource to be shared among whites only. ∗Department of History, Leibniz University of Hannover, Hannover. E-mail: [email protected] The Medieval History Journal, 12, -

Reglas De Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) a Book by Lydia Cabrera an English Translation from the Spanish

THE KONGO RULE: THE PALO MONTE MAYOMBE WISDOM SOCIETY (REGLAS DE CONGO: PALO MONTE MAYOMBE) A BOOK BY LYDIA CABRERA AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION FROM THE SPANISH Donato Fhunsu A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature (Comparative Literature). Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Inger S. B. Brodey Todd Ramón Ochoa Marsha S. Collins Tanya L. Shields Madeline G. Levine © 2016 Donato Fhunsu ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Donato Fhunsu: The Kongo Rule: The Palo Monte Mayombe Wisdom Society (Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe) A Book by Lydia Cabrera An English Translation from the Spanish (Under the direction of Inger S. B. Brodey and Todd Ramón Ochoa) This dissertation is a critical analysis and annotated translation, from Spanish into English, of the book Reglas de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe, by the Cuban anthropologist, artist, and writer Lydia Cabrera (1899-1991). Cabrera’s text is a hybrid ethnographic book of religion, slave narratives (oral history), and folklore (songs, poetry) that she devoted to a group of Afro-Cubans known as “los Congos de Cuba,” descendants of the Africans who were brought to the Caribbean island of Cuba during the trans-Atlantic Ocean African slave trade from the former Kongo Kingdom, which occupied the present-day southwestern part of Congo-Kinshasa, Congo-Brazzaville, Cabinda, and northern Angola. The Kongo Kingdom had formal contact with Christianity through the Kingdom of Portugal as early as the 1490s. -

Politics, Commerce, and Colonization in Angola at the Turn of the Eighteenth Century

Politics, Commerce, and Colonization in Angola at the Turn of the Eighteenth Century John Whitney Harvey Dissertação em História Moderna e dos Descobrimentos Orientador: Professor Doutor Pedro Cardim Setembro, 2012 Dissertação apresentada para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em História Moderna e dos Descobrimentos realizada sob a orientação científica do Professor Doutor Pedro Cardim e a coorientação científica do Professor Doutor Diogo Ramada Curto. I dedicate this dissertation to my father, Charles A. Harvey Jr. (1949-2009), whose wisdom, hard work, and dedication I strive to emulate. The last thing he knew about me was that I was going to study at FCSH, and I hope that I have made him proud. Acknowledgements There are so many people that were instrumental to the production of this dissertation that it would be impossible to include everyone in this space. I want to take the opportunity to thank everyone that supported me emotionally and academically throughout this year. Know that I know who you are, I appreciate everything done for me, and hope to return the support in the future. I would also like to thank the Center for Overseas History for the resources and opportunities afforded to me, as well as all of my professors and classmates that truly enriched my academic career throughout the last two years. There are some people whom without, this would not have been possible. The kindness, friendship, and support shown by Nuno and Luisa throughout this process I will never forget, and I am incredibly grateful and indebted to you both. -

An African Basketry of Heterogeneous Variables Kongo-Kikongo-Kisankasa

ISSN 2394-9694 International Journal of Novel Research in Humanity and Social Sciences Vol. 8, Issue 2, pp: (2-31), Month: March - April 2021, Available at: www.noveltyjournals.com An African Basketry of Heterogeneous Variables Kongo-Kikongo-Kisankasa Rojukurthi Sudhakar Rao (M.Phil Degree Student-Researcher, Centre for African Studies, University of Mumbai, Maharashtra Rajya, India) e-mail:[email protected] Abstract: In terms of scientific systems approach to the knowledge of human origins, human organizations, human histories, human kingdoms, human languages, human populations and above all the human genes, unquestionable scientific evidence with human dignity flabbergasted the European strong world of slave-masters and colonialist- policy-rulers. This deduces that the early Europeans knew nothing scientific about the mankind beforehand unleashing their one-up-man-ship over Africa and the Africans except that they were the white skinned flocks and so, not the kith and kin of the Africans in black skin living in what they called the „Dark Continent‟! Of course, in later times, the same masters and rulers committed to not repeating their colonialist racial geo-political injustices. The whites were domineering and weaponized to the hilt on their own mentality, for their own interests and by their own logic opposing the geopolitically distant African blacks inhabiting the natural resources enriched frontiers. Those „twists and twitches‟ in time-line led to the black‟s slavery and white‟s slave-trade with meddling Christian Adventist Missionaries, colonialists, religious conversionists, Anglican Universities‟ Missions , inter- sexual-births, the associative asomi , the dissociative asomi and the non-asomi divisions within African natives in concomitance. -

Mbele a Lulendo

ø Mbele a lulendo: a study of the provenance and context of the swords found at Kindoki cemetery, Mbanza Nsundi, Bas-Congo Master dissertation by Amanda Sengeløv Key words: power symbol, iron, bakongo, burial rites During the summer excavations carried out by the Kongoking project in the lower-Congo area, five swords where found in the tombs at the Kindoki cemetery. The study of these swords aims to understand the meaning of the deposition of these elite objects in a grave context and trace their provenance. The results of the analysis of these case-studies suggested sixteenth century European hilt types unified with indigenous produced blades. Swords were perceived as power symbols because of the embedded local mentality towards iron, which had a prominent role in the foundation myth of the kingdom. Also the form of the imported sixteenth century swords recalled these local ideas of religion and ideology. The swords had two different meanings; mainly they were used as investiture and where conceived as status symbols, only occasionally they were used as true mbele a lulendo. Mbele a lulendo-swords had a metaphysical connotation and were used during several rites, like executions. Some scholars presume that they used two kinds of swords for these different purposes; the European swords only as status symbols and the native swords as mbele a lulendo. I argue in this dissortation that the European swords where a status symbol as well as true mbele a lulendo. There is not a difference in meaning, but rather a difference in chronology. The European swords were gradually replaced by indigenous fabricated swords, which were inspired by the sixteenth century European examples. -

Trade and the Merchant Community of the Loango Coast in The

Trade and the Merchant Community of the Loango Coast in the Eighteenth Century Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Hull by Stacey Jean Muriel Sommerdyk Honors BA (University of Western Ontario) MA (York University) May 2012 ii Synopsis This thesis explores the political, economic and cultural transformation of the Loango Coast during the era of the transatlantic slave trade from the point of contact with Europeans in the sixteenth century until the end of the eighteenth century, with particular focus on the eighteenth century. While a number of previous studies of the West Central African slave trade have focused principally on the role of the Portuguese on the Angola Coast, this thesis makes a new contribution by evaluating the balance of power between Dutch and Loango Coast merchant communities. In doing so, this thesis concludes that well into the eighteenth century, local African religious and political traditions remained relatively unchanged on the Loango Coast, especially in comparison to their southern neighbours in Angola. Drawing upon detailed records compiled by the Middelburgse Commercie Compangie (MCC), the thesis builds upon an original database which accounts for approximately 10,000 slaves sold by 640 identified African merchants to the Dutch Middelburg Company over the course of 5,000 transactions. Expanding upon the work of Phyllis Martin and other scholars, this thesis highlights a distinction between the Loango and the Angola coasts based on models of engagement with European traders; furthermore, it draws attention to the absence of European credit data in the MCC slave purchasing balance sheets; and, finally, it explores the difficulties involved in procuring slaves via long distance trade. -

Afro-Iberian and West- Central African Influences

African Studies Quarterly | Volume 15, Issue 3 | June 2015 Black Brotherhoods in North America: Afro-Iberian and West- Central African Influences JEROEN DEWULF Abstract: Building on the acknowledgement that many Africans, predominantly in West- Central Africa, had already adopted certain Portuguese cultural and religious elements before they were shipped to the Americas as slaves, this article argues that syncretic Afro-Iberian elements must also have existed among slave communities outside of the Iberian realm in the American diaspora. It explores this possibility with a focus on Afro- Iberian brotherhoods. While it was long assumed that these so-called “black brotherhoods” were associated with slave culture on the Iberian Peninsula and in Latin America only, it can now be confirmed that Afro-Catholic fraternities also flourished in parts of Africa during the Atlantic slave trade era. A comparative analysis of king celebrations in Afro-Iberian brotherhoods with those at Pinkster and Election Day festivals in New York and New England reveals a surprising number of parallels, which leads to the conclusion that these African-American performances may have been rooted in Afro-Iberian traditions brought to North America by the Charter Generations. Introduction When Johan Maurits of Nassau, Governor-General of Dutch Brazil (1630-54), sent out expeditions against the maroons of Palmares, he was informed by his intelligence officers that the inhabitants followed the “Portuguese religion,” that they had erected a church in the capital, that there were chapels with images of saints and the Virgin Mary and that Zumbi, the king of Palmares, did not allow the presence of “fetishists.” Portuguese sources confirm that Palmares had a priest who baptized children and married couples and that its inhabitants followed Catholic rite, although according to Governor Francisco de Brito, they did so “in a stupid fashion.”1 Many more examples of the existence of Afro-Catholic elements in maroon communities in Latin America can be found. -

Catalina Loango De Angola En La Tradición Oral Del Palenque De San Basilio

CATALINA LOANGO DE ANGOLA EN LA TRADICIÓN ORAL DEL PALENQUE DE SAN BASILIO. ALGUNOS ELEMENTOS COMPARATIVOS DE ESTA FIGURA CON EL MITO DEL MOHÁN INDIGENA. Jeniffer Rojas Díaz Universidad del Valle Facultad de Humanidades Escuela de Ciencias del Lenguaje Licenciatura en Lenguas Extranjeras Santiago de Cali, Valle 2016 CATALINA LOANGO DE ANGOLA EN LA TRADICIÓN ORAL DEL PALENQUE DE SAN BASILIO. ALGUNOS ELEMENTOS COMPARATIVOS DE ESTA FIGURA CON EL MITO DEL MOHÁN INDIGENA Monografía de grado para optar por el título de Licenciada en lenguas extranjeras inglés-francés Jeniffer Rojas Díaz Directora: Dr. Lirca Vallés Universidad del Valle Facultad de Humanidades Escuela de Ciencias del Lenguaje Licenciatura en Lenguas Extranjeras Santiago de Cali, Valle 2016 DEDICATORIA Quiero dedicar este trabajo a mi adorada mamá, hermana, tíos, abuelos quienes forjaron con determinación mis cimientos como ser humano y mujer. A la comunidad afrocolombiana y en particular a los palenqueros cuya asombrosa riqueza cultural teñida de templanza y valentía permearon mi curiosidad e imaginación. Además, dedico este gran esfuerzo a una de las mujeres más valerosas que ha cruzado por mi camino, Lirca Vallés, quien con su sabiduría y maternal guianza encantó mi ser de maravillosas historias sobre África, las cuales han quedado grabadas indisolubles en mi memoria. AGRADECIMIENTOS Infinitas gracias por su constancia en este camino de construcción personal y crecimiento intelectual a mi adorada mamá, abuelos, a mi hermana Nathalie Rojas por su guía, a mi tío Vladimir por su apoyo y a cada una de las personas que han permanecido a mi lado durante estos años iluminando en primavera e invierno mi camino. -

King Leopold Ii‟S Exploitation of the Congo from 1885 to 1908 and Its Consequences

KING LEOPOLD II‟S EXPLOITATION OF THE CONGO FROM 1885 TO 1908 AND ITS CONSEQUENCES by STEVEN P. JOHNSON A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in History in the College of Arts and Humanities and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2014 Thesis Chair: Dr. Ezekiel Walker ABSTRACT This thesis argues that King Leopold II, in his exploitation of the Congo, dealt the Congo a future of political, ethnic, and economic destabilization. At one time consisting of unified and advanced kingdoms, the Congo turned to one completely beleaguered by poverty and political oppression. Leopold acquired the Congo through unethical means and thus took the people‟s chances away at self-rule. He provided for no education or vocational training, which would stunt future Congolese leaders from making sound economic and political policies. Leopold also exploited the Congo with the help of concession companies, both of which used forced labor to extract valuable resources. Millions of Congolese died and the Congo itself became indebted through Belgian loans that were given with no assurance they could ever truly be paid back due to the crippled economy of the Congo. With the Congo now in crippling debt, the current president, Joseph Kabila, has little incentive to invest in reforms or public infrastructure, which stunts economic growth.1 For over a century the Congo has been ruled by exploitative and authoritarian regimes due to Leopold‟s initial acquisition. The colonization from Leopold lasted from 1885-1908, and then he sold it to his home country of Belgium who ruled the Congo from 1908 to 1960. -

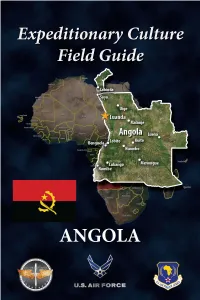

ECFG-Angola-2020R.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. ECFG The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Angola Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” Angola, focusing on unique cultural features of Angolan society and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture- general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. All human beings have culture, and individuals within a culture share a general set of beliefs and values. -

A Level History a African Kingdoms Ebook

Qualification Accredited A LEVEL EBook HISTORY A H105/H505 African Kingdoms: A Guide to the Kingdoms of Songhay, Kongo, Benin, Oyo and Dahomey c.1400 – c.1800 By Dr. Toby Green Version 1 A LEVEL HISTORY A AFRICAN KINGDOMS EBOOK CONTENTS Introduction: Precolonial West African 3 Kingdoms in context Chapter One: The Songhay Empire 8 Chapter Two: The Kingdom of the Kongo, 18 c.1400–c.1709 Chapter Three: The Kingdoms and empires 27 of Oyo and Dahomey, c.1608–c.1800 Chapter Four: The Kingdom of Benin 37 c.1500–c.1750 Conclusion 46 2 A LEVEL HISTORY A AFRICAN KINGDOMS EBOOK Introduction: Precolonial West African Kingdoms in context This course book introduces A level students to the However, as this is the first time that students pursuing richness and depth of several of the kingdoms of West A level History have had the chance to study African Africa which flourished in the centuries prior to the onset histories in depth, it’s important to set out both what of European colonisation. For hundreds of years, the is distinctive about African history and the themes and kingdoms of Benin, Dahomey, Kongo, Oyo and Songhay methods which are appropriate to its study. It’s worth produced exquisite works of art – illustrated manuscripts, beginning by setting out the extent of the historical sculptures and statuary – developed complex state knowledge which has developed over the last fifty years mechanisms, and built diplomatic links to Europe, on precolonial West Africa. Work by archaeologists, North Africa and the Americas. These kingdoms rose anthropologists, art historians, geographers and historians and fell over time, in common with kingdoms around has revealed societies of great complexity and global the world, along with patterns of global trade and local interaction in West Africa from a very early time.