Regno del Congo

1

Regno del Congo

Kongo

Descrizione generale

Regno del Kongo Kongo dya Ntotila bantu, kikongo M'banza-Kongo

Forma politica

Reame

Nome completo: Nome ufficiale: Lingua ufficiale: Capitale:

- Nascita:

- 1395 con Lukeni lua Nimi

- Fine:

- 1914 con Manuel III del Congo

Territorio e popolazione

Bacino geografico: Massima estensione: 129,400 km² nel 1650

- Popolazione:

- 509.250 nel 1650

Economia

Religione e Società

Religioni preminenti: Cristianesimo

Evoluzione storica

Preceduto da: Succeduto da:

Regno del Congo

2

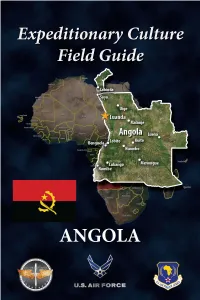

Il Regno del Congo (o Impero del Congo, Kongo dya Ntotila o Wene wa Kongo in kikongo) fu un regno

dell'Africa Occidentale nel periodo fra il XIV secolo (circa 1395) e l'inizio del XX secolo (1914). Il territorio dell'impero includeva l'attuale Angola settentrionale (inclusa l'enclave della Provincia di Cabinda), la Repubblica del Congo, e la parte occidentale della Repubblica Democratica del Congo. Nel periodo della sua massima potenza, controllava un territorio che si estendeva dall'Oceano Atlantico a ovest fino al fiume Kwango a est, e dal fiume Congo a nord fino al fiume Kwanza a sud. Il regno comprendeva numerose province, e godeva del rapporto di vassallaggio di molti regni circostanti, come quelli di N'goyo, Kakongo, Ndongo e Matamba. Il monarca dell'impero era chiamato Manikongo.[1] L'etnia principale del regno era quella dei Bakongo o Essikongo, appartenente al più grande gruppo etnolinguistico dei Bantu.

Storia

Fonti

Gran parte di quanto si ipotizza sulla storia antica del Regno del Congo (precedente all'inizio dei rapporti con i portoghesi) deriva dalla tradizione orale locale, trascritta dagli Europei per la prima volta nel tardo XVI secolo. Particolarmente importante è il corpus di racconti trascritti dal missionario cappuccino italiano Giovanni Cavazzi da Montecuccolo alla metà del XVII secolo. Fra le opere più moderne dello stesso genere si deve citare Nkutama a mvila za makanda, una raccolta di racconti tradizionali pubblicata in kikongo nel 1934 dal missionario redentorista Jean Cuvelier. Una porzione di questi racconti è stata tradotta in francese da Cuvelier, e pubblicata col titolo

Traditions congolaise (1930).

La validità storica di questi racconti non è stata accertata. Soprattutto per quanto riguarda le origini del regno, è possibile che i racconti della tradizione orale riflettano una rielaborazione della storia del Congo a vantaggio della dinastia di Mbanza Congo, che emerse probabilmente su altre dimenticate o sottovalutate nella tradizione. Uno degli storici che ha affrontato in modo più approfondito il tema della nascita del Regno del Congo è John Thornton.

A partire dal XVI secolo la presenza europea in Congo divenne più importante, e la scrittura si diffuse presso l'elite aristocratica del regno. Di conseguenza, su questo periodo esiste un'abbondante documentazione, che include resoconti dei viaggiatori europei, documenti formali di governo e diplomatici, materiale epistolare e altro.

Nascita del Regno

Nonostante le scarse ricerche archeologiche svolte finora nella zona, è certo che il primo nucleo del regno del Congo si sia formato da qualche parte lungo il basso corso del fiume Congo. I Bakongo giunsero nella zona probabilmente da nord, nel contesto dei movimenti migratori che coinvolsero gran parte dei popoli bantu. Praticarono l'agricoltura almeno dal X secolo a.C., e la lavorazione del ferro almeno dal IV. Scavi archeologici presso Madingo Kayes (sulla costa atlantica) hanno dimostrato che già dei primi secoli dell'era volgare erano presenti nella zona società complesse e strutturate. Mancano ancora studi approfonditi sull'evoluzione delle ceramiche, ma pare che lo stile che era prevalente all'epoca dei primi resoconti storici sul Regno del Congo (1483) fosse adottato almeno dal XII secolo. Gli scavi a Mbanza Kongo eseguiti fra gli anni sessanta e settanta da Fernando Batalha hanno portato alla luce materiale che potrebbe risalire a un periodo ancora più antico.

Secondo la tradizione, il primo nucleo del regno fu lo stato di Mpemba Kasi, situato di poco a sud dell'odierna Matadi (Repubblica Democratica del Congo). La dinastia di Mpenda Kasi estese il proprio dominio lungo la valle del fiume Kwilu; i monarchi di questo periodo sarebbero stati sepolti in un luogo sacro chiamato Nsi Kwilu (letteralmente "la patria dei Kwilu" secondo Thornton; forse la capitale del regno). Montesarchio riporta che secondo la tradizione locale, Nsi Kwilu era un luogo talmente sacro che il solo vederlo avrebbe causato la morte del profanatore. Ancora nel XVII secolo, il regnante di Mpenda Kasi veniva chiamato "madre del re del Congo".

Intorno al 1375 Nimi a Nzima, re di Mpemba Kasi, si alleò con Nsaku Lau, sovrano del vicino regno di Mbata, unificando le due linee di successione.

Regno del Congo

3

Lukeni lua Nimi (chiamato anche Nimi a Lukeni) fu il primo erede comune dei regni di Mpenba Kasi e Mbata, e viene ricordato come il fondatore del regno del Congo. La nascita del regno si fa coincidere con la conquista di Mwene Kabunga, un regno situato a sud presso il monte Mongo dia Kongo (letteralmente "il monte del Congo"), avvenuta intorno al 1400. Lukeni lua Nimi trasferì la propria capitale a Mbanza Kongo, presso il monte del Congo. Ancora nel XVII secolo, i discendenti di Mwene Kabunga ricordavano la conquista in una rievocazione simbolica.[2] Si è ipotizzato che Mwene Kabunga rappresenti una dinastia precedente, sconfitta da quella iniziata da Lukeni lua Nimi.

Espansione

Il sistema elettorale stabilito dall'alleanza di Mpemba Kasi e Mbata prevedeva che Lukeni lua Nimi passasse la corona non al proprio figlio, ma al figlio di uno dei suoi fratelli, Nanga. La corona passò poi a un altro nipote della famiglia reale, Nlaza, e infine al figlio di Lukeni lua Nimi, Nkuwu a Lukeni, nel 1440. Quando i portoghesi giunsero per la prima volta in Africa Occidentale, sul Congo regnava Nzinga a Nkuwu, figlio ed erede di Nkuwu a Lukeni.

I primi re della dinastia continuarono a

La capitale dell'impero del Congo, oggi São Salvador

espandere i confini dell'impero. Alcuni stati, come Mpangu, Nkusu e Wandu, si unirono volontariamente al regno; altri (tra cui Nsundi e Mbamba) furono conquistati. Dai resoconti di Duarte Lopes e altre fonti del XVI secolo si evince che il regno giunse a comprendere oltre venti province, delle quali le più importanti erano Nsundi a nordest, Mpangu al centro, Mbata nel sudest, Soyo del sudovest e Mbamba e Mpemba a sud. I titoli monarchici in uso nel XVI secolo suggeriscono inoltre che numerosi regni circostanti fossero soggetti all'autorità del re del Congo, secondo una relazione simile a quella del vassallaggio europeo. Erano stati vassalli, tra l'altro, i regni di Vungu, Kakongo e N'Goyo e alcuni regni di lingua kimbundu come Matamba, Ndongo (talvolta identificato erroneamente con l'Angola) e Kisama.

Gran parte del potere del re del Congo veniva dalla notevole concentrazione di popolazione attorno al centro di Mbanza Kongo, che si trova in una regione rurale scarsamente popolata (meno 5 persone per km²). I primi portoghesi, giunti alla fine del XV secolo, descrissero Mbanza Kongo come una grande città, paragonabile ad alcuni centri urbani europei (per esempio Évora, in Portogallo). Sebbene non ci siano dati certi sulla popolazione del Congo in questo periodo, le stime successive (come quelle stesse ricavate dai registri battesimali stese dai missionari Gesuiti) indicano che l'area della capitale raccogliesse circa un quinto della popolazione complessiva dell'impero, per un totale di circa 100.000 abitanti. Questa concentrazione forniva al re del Congo un ampio serbatoio di risorse da cui attingere e soldati da reclutare.

Regno del Congo

4

Contatto con i portoghesi

Il primo europeo a visitare il Regno del Congo fu l'esploratore portoghese Diogo Cão, che visitò la costa africana fra il 1482 e il 1483. Durante la sua permanenza in Congo, Cão rapì alcuni membri della nobiltà del regno, portandoli come prigionieri in Portogallo. Due anni dopo, quando Cão riportò gli ostaggi, il re Nzinga a Nkuwu acconsentì a convertirsi al cristianesimo. Nel 1491 Nzinga a Nkuwu e molti altri nobili (a partire dal governatore della provincia di Soyo) furono battezzati da preti cattolici appositamente inviati dal Portogallo. Nzinga a Nkuwu cambiò il proprio nome in Giovanni I (João I) in onore del re portoghese dell'epoca, Giovanni II.

A Giovanni I (morto intorno al 1509) succedette suo figlio Mvemba a Nzinga, che prese il nome di Afonso I. Alla successione tentò di opporsi un fratellastro di Afonso, Mpanzu a Kitima; Afonso lo sconfisse in una celebre battaglia a Mbanza Congo. In seguito, Afonso I spiegò di aver avuto un presagio di vittoria in cui gli erano apparsi San Giovanni e la Vergine Maria. In seguito a questo episodio, il 25 luglio (festa di San Giovanni) divenne festa nazionale del regno; alla sua visione Afonso si ispirò anche nel disegnare il primo simbolo del regno, rimasto in uso fino al 1860.

Il simbolo del Regno del Congo ideato da Afonso

I

Afonso I dedicò parte della propria attività politica a favorire lo sviluppo della Chiesa cattolica in Congo. Lo stesso re, con l'aiuto di consiglieri portoghesi come Rui d'Aguiar, si dedicò personalmente a sviluppare una versione sincretica del cristianesimo adatta alla cultura congolese e che potesse quindi essere diffusa efficacemente presso le masse. Una quota fissa dei proventi dell'erario venne dedicata alla costruzione di chiese e alla formazione del clero congolese. Il compito di organizzare il clero nel regno fu affidato a Enrico, che era stato ordinato prete in Europa e dal 1518 era vescovo di Utica.

Il contatto con gli Europei portò il rapido sviluppo del commercio degli schiavi, una pratica già diffusa nella cultura dell'Africa Occidentale. Afonso mostrò qualche segno di preoccupazione rispetto all'aumentare delle proporzioni del fenomeno, e nel 1526 chiese a Giovanni III, re del Portogallo, di prendere provvedimenti nei confronti dei portoghesi che si dedicavano a questa attività in modo spregiudicato.