A Case Study of GMO Scientist Kevin Folta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Temple Grandin Ingrid Newkirk

Lesson to Grow Google Lies, Wikipedia Stinks and Siri Doesn’t Even Go Here Description: Grade Level: 9-12 Students will learn how to determine reliable information sources on the internet to develop fact-based writing about agricultural topics. Essential Skills: 1,2, 4. 5, 9 Background: It can be difficult for students to distinguish reputable, accurate sources. In this CCSS: 9-10.RI.4, 9-10.RI.7, lesson, students learn what characteristics to look for on a website to determine the 9-10.W.1, 9-10.W.8, 9-10 W.9, validity of the information being provided. Students will learn to identify credible 11-12.W.8, 11-12.W.9, 11-12. website sources for agricultural related topics. RI.4, 11-12.RI.7, 11-12.W.1 Directions: Part I: Celebrity Sources Time: 2 class periods 1) Divide students into small groups of 2-3 students, provide each group with a stack of Celebrity Cards with instructions to keep the picture side up with no Materials: Google Lies Kit* peeking at the back. 6 Celebrity Cards (set per 2) Today, we are going to look at determining if a source is credible with regards group)* to agriculture. Each group has a stack of cards face up in front up of them with a 5 Heads up Cards (set per picture of a celebrity and a name. You may not know some of them and that’s okay. group)* As a group, you will rank these in order of how trustworthy they would be to use a 5 Gallery Walk Papers source for agricultural purposes. -

CFI-Annual-Report-2018.Pdf

Message from the President and CEO Last year was another banner year for the Center the interests of people who embrace reason, for Inquiry. We worked our secular magic in a science, and humanism—the principles of the vast variety of ways: from saving lives of secular Enlightenment. activists around the world who are threatened It is no secret that these powerful ideas like with violence and persecution to taking the no others have advanced humankind by nation’s largest drugstore chain, CVS, to court unlocking human potential, promoting goodness, for marketing homeopathic snake oil as if it’s real and exposing the true nature of reality. If you medicine. are looking for humanity’s true salvation, CFI stands up for reason and science in a way no look no further. other organization in the country does, because This past year we sought to export those ideas to we promote secular and humanist values as well places where they have yet to penetrate. as scientific skepticism and critical thinking. The Translations Project has taken the influential But you likely already know that if you are reading evolutionary biology and atheism books of this report, as it is designed with our supporters in Richard Dawkins and translated them into four mind. We want you not only to be informed about languages dominant in the Muslim world: Arabic, where your investment is going; we want you to Urdu, Indonesian, and Farsi. They are available for take pride in what we have achieved together. free download on a special website. It is just one When I meet people who are not familiar with CFI, of many such projects aimed at educating people they often ask what it is we do. -

GENETICS of TREE ARCHITECTURE in PEACH (Prunus Persica (L.) Batsch)

GENETICS OF TREE ARCHITECTURE IN PEACH (Prunus persica (L.) Batsch) By OMAR CARRILLO MENDOZA A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2012 1 © 2012 Omar Carrillo Mendoza 2 To my wife Patricia and my Mom Marcela with love 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am thankful to my advisor Dr. Jose Chaparro and retired professor Dr. Wayne Sherman, it has been a pleasure to learn from them and be part of the Stone Fruit Breeding Program. To the members of my committee: Dr. Rebecca Darnell, Dr. Kevin Folta, Dr. Matias Kirst and Dr. Jeffrey Williamson for all the guidance during my research. To Dr. James W. Olmstead for allowing me and Patricia for teaching me how to use the real time PCR machine. To Bruce Topp, Jean-Clement Marceillou, Jose Gandia, Jorge Rodriguez, Mohamed Benzit, Paul Lyrene and Thomas Beckman for sharing their experience. To Mark Gal, Cecil Shine, and John Thomas for their valuable help on the farm. To Valerie for her support in the lab. To Elia Ulivi and Dario Chavez for helping me to take field data. To my friends, Andres, Aparna, Divya, Marga, Mitra, Octavio, Preeti, Silvia,Yuan and especially Kendra for their friendship and kindness. To my Mexican fellows: Alberto, Aurora, Miriam, Nicacio, Oscar, Paola, Paula and Sebastian for helping me to adjust to my new home and reminding me my beloved home country. I am especially grateful to CONACYT and the people of Mexico for granting me with a scholarship that made possible this achievement. -

The North American Leaders Session on Agricultural Technology And

2017 North American Leaders Session on Agricultural Technology and Innovation April 5 – 6, 2017 Disney’s Coronado Springs Resort #CFI17 The North American Leaders Session on Agricultural Technology and Innovation brings together leadership from broad agriculture coalitions and state commodity organizations responsible for earning trust in today’s food system. CFI’s role is to facilitate an information exchange and strategy development that connects individual and organizational efforts. Participants will have the opportunity to discuss programs, celebrating successes and learning from challenges. This meeting provides leaders with a platform to share current programs and also gather insights on how to best reach their key target audiences. Meeting Objectives Connect state and national efforts related to biotechnology and on-farm sustainability practices. Share current programs and insights on how to best reach influencers and regulators. Identify strategies to reach influencers and regulators. Logistics Attendees will hear from a variety of leaders from both attending organizations and allied organizations that can “set-the-stage” for collaborative and educational discussions. Following each presentation there will be ample time for questions and answers as well as an opportunity during state-sharing to highlight key take-a-ways and learnings for strategic direction. After the meeting, CFI will distribute all the strategies to all attendees. Wednesday, April 5 Meeting Room: Durango 1 & 2; Reception and Dinner: Monterrey 1, 2, 3 8:00 a.m. Registration Open 9:00 a.m. Welcome Philip Lobo, United Soybean Board Terry Fleck, The Center for Food Integrity 9:30 a.m. Overview of CFI Technology and Innovation Outreach Terry Fleck, The Center for Food Integrity The Center for Food Integrity is a leader in consumer trust research and a number of research topics have explored how to better communicate with consumers on issues – like technology and innovation, that are complex and at times controversial. -

Influence of Year and Genetic Factors on Chilling Injury

Euphytica DOI 10.1007/s10681-011-0572-1 Influence of year and genetic factors on chilling injury susceptibility in peach (Prunus persica (L.) Batsch) Pedro J. Martı´nez-Garcı´a • Cameron P. Peace • Dan E. Parfitt • Ebenezer A. Ogundiwin • Jonathan Fresnedo-Ramı´rez • Abhaya M. Dandekar • Thomas M. Gradziel • Carlos H. Crisosto Received: 30 August 2011 / Accepted: 29 October 2011 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2011 Abstract Chilling injury (CI) is a major physiolog- susceptibility factors and/or experiences inducing ical problem limiting consumption and export of peach conditions. The F-M locus also greatly influences and nectarine (Prunus persica (L.) Batsch). To clarify susceptibility to flesh bleeding, although the physio- the genetic basis for chilling injury, inheritance of the logical mechanism for this disorder is unclear and may major CI symptoms mealiness, flesh browning, flesh be controlled by a different gene closely linked to bleeding, and flesh leatheriness were examined over endoPG. Unlike mealiness, flesh bleeding occurred three years in two related peach progenies. In addition, primarily in non-melting flesh fruit, particularly when genetic relationships among traits and the year-to-year the fruit is white-fleshed. Flesh browning incidence variation in trait performance in these progenies were was greater in mealy fruit and was not associated with tracked. Both populations also segregated for Free- flesh bleeding. Breeding for CI resistance is thus a stone-Melting flesh (F-M) and yellow flesh. There viable long-term strategy to reduce losses in the fresh were significant differences in CI symptoms among and processed peach and nectarine industries. -

Oral Session Abstracts ORALS–MONDAY 102Nd Annual International Conference of the American Society for Horticultural Science Las Vegas, Nevada

Oral Session Abstracts ORALS–MONDAY 102nd Annual International Conference of the American Society for Horticultural Science Las Vegas, Nevada Presenting authors are denoted by an astrisk (*) the CP treatment had a higher Area Under the Disease Progress Curve than the NST treatment in tomato in 2003. Overall, disease pressure was highest in tomato in 2001. But disease levels within years were Oral Session 1—Organic Horticulture mostly unaffected by amendment treatments. In cabbage, disease was more common in 2002 than in 2003, although head rot was more Moderator: Matthew D. Kleinhenz prevalent in compost-amended plots in 2003 than in manure-amended 18 July 2005, 2:00–4:00 p.m. Ballroom H or control plots. Tomato postharvest quality parameters were similar among amendment and weed treatments within each year. Soil amend- Weed Control in Organic Vegetable Production: The Use ment may enhance crop yield and quality in a transitional-organic of Sweet Corn Transplants and Vinegar system. Also, weed management strategy can alter weed populations and perhaps disease levels. Albert H. Markhart, III *1, Milton J. Harr 2, Paul Burkhouse 3 Consumer Sensory Evaluation of Organically and Con- 1University of Minnesota, Horticultural Science, 223 Alderman Hall, St. Paul, MN, 55108; 2Southwest State University, Southwest Research and Outreach Center, Lamberton, MN, ventionally Grown Spinach 56512; 3Farm, Foxtail Farm, Shafer, MN, 55074 Xin Zhao *1, Edward E. Carey 1, Fadi M. Aramouni2 Weed control in organic vegetable production is a major challenge. 1Kansas State University, Horticulture, Forestry and Recreation Resources, 2021 Throck- During Summer 2004, we conducted fi eld trials to manage weeds in morton Hall, Manhattan, KS, 66506; 2Kansas State University, Animal Sciences and organic sweet corn, carrots and onions. -

JCOM 20(04)(2021)A09 2 Their Opinion Matches the Group’S Opinion, They Will Share It

COM Silent science: a mixed-methods analysis of faculty J engagement in science communication Taylor K. Ruth, Joy N. Rumble, Lisa K. Lundy, Sebastian Galindo, Hannah S. Carter and Kevin Folta Abstract To address science literacy issues, university faculty have to engage in effective science communication. However, social pressures from peers, administration, or the public may silence their efforts. The purpose of this study was to understand the effect of the spiral of silence on faculty’s engagement with science communication. A survey was distributed to a census of tenure-track faculty at the University of Florida [UF], and the findings did not support the spiral of silence was occurring. However, follow-up interviews revealed faculty did not perceive their peers to value science communication and were more concerned about how the public felt about their research and communication. Keywords Public understanding of science and technology; Science communication: theory and models DOI https://doi.org/10.22323/2.20040209 Submitted: 7th September 2020 Accepted: 17th April 2021 Published: 26th July 2021 Context The definition for science literacy has expanded from once only including individuals’ ability to understand science [American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), 1990] to include ability to apply that knowledge along with perceptions and trust in science [National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NAS), 2016]. Recent research has concluded the public has an adequate understanding of scientific topics; however, knowledge gaps have been identified across demographic groups, like education and gender [Funk and Kehaulani Goo, 2015; National Science Board (NSB), 2016]. These knowledge gaps underscore the need for targeted science literacy efforts. -

Filing # 60386344 E-Filed 08/14/2017 05:46:36 PM

Filing # 60386344 E-Filed 08/14/2017 05:46:36 PM IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF THE EIGHTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT ALACHUA COUNTY, FLORIDA CIVIL ACTION US RIGHT TO KNOW, Plaintiff, v. CASE NO.: 01-2017-CA-2426 THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA BOARD OF TRUSTEES, Defendant. ___________________________________/ REPLY IN SUPPORT OF COMPLAINT FOR WRIT OF MANDAMUS Plaintiff, US Right to Know, pursuant to this Court’s Order dated July 13, 2017, respectfully submits this Reply to the Defendant’s Response to Plaintiff’s Complaint for Writ of Mandamus and Order to Show Cause. The AgBioChatter Group Emails The parties appear to agree on the general parameters of the applicable law. Plaintiff has a constitutional and statutory right to access non-exempt records “made or received in connection with the official business” of the University of Florida. Art. I, § 24(a), Fla. Const.; see also § 119.011(12), Fla. Stat. (2016). This includes any material “which is intended to perpetuate, communicate, or formalize knowledge of some type.” Shevin v. Byron, Harless, Schaffer, Reid and Associates, Inc., 379 So. 2d 633, 640 (Fla. 1980). This does not include communications that are “private” or “personal,” because such communications are not made or received in connection with official business. State v. City of Clearwater, 863 So. 2d 149, 155 (Fla. 2003). Private documents do not become public records solely by being placed on an agency-owned computer. Id. at 154. Plaintiff parts ways with Defendant, however, upon the Defendant’s remarkable assertion that the emails between Professor Folta and the AgBioChatter group are “private” or “personal” and therefore fall within the scope of City of Clearwater and its progeny. -

Small Fruit News Small Fruit Consortium Volume 11, No

the Southern Region Small Fruit News small fruit consortium Volume 11, No. 2 April 2011 Special Reports Why Cut-offs May Make NC State University Sense for Your Clemson University Strawberry Operation The University of Arkansas Blackberry and Spring 2011 The University of Georgia Raspberry The University of Tennessee Seasonal Checklist VA Polytechnic Institute and State University In this issue Strawberry Growers Spring Checklist We actually did this in 2009-2010 at Central Special Reports: Crops Research Station in Clayton, NC, and there was no financial support for this study. We Why Cut-offs May Make Sense for Your did, however, receive free plant material (and Strawberry Operation shipping) from Lassen Canyon Nursery, Redding, CA. In this brief article I will be sharing E. Barclay Poling some preliminary results from this Chandler plant Professor Emeritus, type trial at Clayton as well as try to address a Department of Horticultural Science more fundamental concern of all growers – how NC State University do you go about optimizing both marketable yield and berry size with different plant types and The winter season is always good time to review planting dates? what’s happening with newer varieties and types of strawberries for plasticulture production. For In reality, there are a number of important example, in 2010 we tested a newer day-neutral considerations to take into account in deciding variety with over a dozen growers in several states which type of transplant is best for your (with a Tobacco Trust Fund Commission grant), operation (and market), and it doesn’t just come and I am really looking forward to getting some down to measuring plant yield! feedback from these trials in 2011. -

New York Berry News CORNELL UNIVERSITY

New York Berry News CORNELL UNIVERSITY Volume 09, Number 12 December 13, 2010 What’s Inside CURRANT EVENTS 1. Currant Events January 6-7, 2011. NARBA (North American Raspberry and th Blackberry Growers Association) Annual Meeting, Savannah, a. NYBN Celebrates 10 Anniversary in GA. For more information: Debby Wechsler, 919-542-4037 or 2011 [email protected], or b. 2011 Cornell Pest Management http://www.raspberryblackberry.com/. January 27, 2011. Empire State Fruit and Vegetable EXPO Guidelines for Berry Crops Now Available berry session. Mark your calendar now - details to follow in the c. Products Approved for Brown Marmorated next issue. Stink Bug and Spotted Wing Drosophila January 31 – February 3, 2011. Mid-Atlantic Fruit and Management in NYS Vegetable Convention at the Hershey Lodge in Hershey, PA. For more information visit www.mafvc.org. d. Get GAPS training On Line e. An Invitation to the North American February 8-11, 2011. 7th North American Strawberry Symposium and joint North American Strawberry Growers Strawberry Growers Conference Association Meeting. Tampa, Florida. Program and details f. CleanSweep NY 2010 Fall Collection follow below. For more information: Kevin Schooley, 613-258- 4587, or [email protected] or http://www.nasga.org/. Results March 5, 2011. Planting, Cultivating, and Marketing g. Council on Food Policy Issues Report Juneberries in the Great Lakes Region. NYS Agricultural h. Rural Environmental Quality and Experiment Station, Geneva, NY. For more information: Nancy Anderson (585) 394-3977 x427 or e-mail [email protected]. Energy Efficiency Grants Available i. Sign Up Now for Federal Programs June 22-26, 2011. -

Say Aloha to Plant Biology 2017!

January/February 2017 • Volume 44, Number 1 p. 5 p. 7 p. 9 Say Aloha to Plant ASPB Members Good Science Biology 2017! Elected to Conquers Greatest 2016 Class of Fear: The Unknown June 24–28 AAAS Fellows Honolulu, Hawaii THE NEWSLETTER OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF PLANT BIOLOGISTS President’s Letter Adjusting to an Uncertain Future BY SALLY MACKENZIE University of Nebraska–Lincoln s we enter 2017, plant is a seeming lack of respect biologists face uncer- by the new government for Atainty with the arrival science, its process, and its Aloha! of President Trump. The new importance to America’s administration has provided health, safety, food security, few hints about a position on and technological advantage. science, and what comments Now more than ever, it will have been made appear worri- be crucial that we justify the some. A Trump administration value of science not simply is not what most of us were for science’s sake, but as expecting based on polling the engine that fuels U.S. June 24–28 data and, in fact, was not what competitiveness. Comments by the Trump Honolulu, Hawaii biologists had hoped for. A Sally Mackenzie 2013–2014 survey found that campaign regarding climate FIVE MAJOR SYMPOSIA only 5% to 6% of self-described profes- change, safety of vaccinations, and envi- sional biologists considered themselves ronmental protection raise the question of Away from the Brink—Toward the Sustainable Use of N and P in whether sound science will hold sway in “conservative” or “far right” in political views Agriculture (Reardon, 2016). -

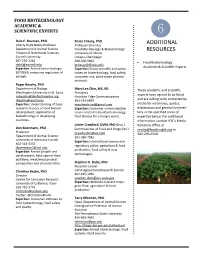

Additional Resources

FOOD BIOTECHNOLOGY ACADEMIC & SCIENTIFIC EXPERTS 6 Dale E. Bauman, PhD Bruce Chassy, PhD Liberty Hyde Bailey Professor Professor Emeritus ADDITIONAL Department of Animal Science Food Microbiology & Biotechnology RESOURCES Division of Nutritional Sciences University of Illinois, Cornell University Urbana-Champaign 607-255-2262 208-306-9062 Food Biotechnology [email protected] [email protected] Academic & Scientific Experts Expertise: Animal biotechnology; Expertise: Broad scientific and policy BST/BGH; endocrine regulation of issues on biotechnology; food safety, animals. consumer risk; plant-made pharma- ceuticals. Roger Beachy, PhD Department of Biology Mary Lee Chin, MS, RD These academic and scientific Washington University in St. Louis President experts have agreed to be listed [email protected] Nutrition Edge Communications [email protected] 303-333-6854 and are willing to be contacted by Expertise: Understanding of basic [email protected] media for interviews, quotes, research; history of food biotech Expertise: Consumer communication explanation and general commen- development; application of issues related to food biotechnology; tary in the specified areas of biotechnology in developing food choices for a hungry world. expertise below. For additional countries. information, contact IFIC’s Media Lester Crawford, DVM, PhD (hon.) Relations Office at Don Beermann, PhD Commissioner of Food and Drugs (ret.) [email protected] or Professor [email protected] 202-296-6540. Department of Animal Science 202-380-7981