Flow on Stage the Art of Sustainable Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Judo Der Behinderten

der 9 / 2008 September K 10339 2,65 EUR budoka www.budo-nrw.de der Internationale Deutsche Goshin-Jitsu Ausbildung Kursleiter 9 / 2008 September K 10339 2,65 EUR budoka Einzelmeisterschaften Frauen-SB und -SV www.budo-nrw.de der U 20 in Berlin ................. 10 Jubiläumslehrgang in in Hagen ................................54 Deutsche Hochschulmeis- Reichshof-Eckenhagen ......... 45 Lehrgang in Köln ..................54 terschaften in Köln ................11 Dan-Vorbereitungslehrgang .. 46 Lehrgang in Littfeld ..............54 Deutsche Meisterschaften Fun- und Sportweekend ........47 Lehrgang in Hagen ................55 der Frauen und Männer Ausschreibungen ................... 47 Kata-Lehrgang in Stolberg ....55 über 30 Jahre .........................12 Jugendlehrgang ..................... 56 World Masters ü30 Landeslehrgang Vorberei- in Brüssel .............................. 12 Hapkido tung 1. Kyu in Stolberg .........57 Internationale Turniere ..........13 Aus den Vereinen ..................48 Bezirksprüfung in Hamm ......57 Trainingslager in Celje/ Dan-Lehrgang ....................... 48 Dan-Prüfung in Nettetal ........58 Slowenien .............................. 15 Ausschreibungen ................... 58 21. Sommerschule der NWJV-Jugend in Hennef ...... 16 JJU NW Jiu-Jitsu Lehrgang in Wuppertal.......... 60 Self-Control-Training- DJJB LV NW System ................................... 60 „der budoka“ 9/2008 Prüferlizenzlehrgang Kata-Training ........................ 61 Titelbild: Miriam Dunkel von in Hohenlimburg ...................50 -

Artikel in De Defensiekrant

nummer 36 defensiekranT 27 oktober 2011 Eindelijk gevonden Genezeriken doen een- 4 tweetje met luchtmacht Bewogen diploma- 5 uitreiking Kunduz ‘Mijn tijd als topsporter 6 was tijdelijk’ Unieke expositie 7 Afghanistan CasTriCum Bijna zeventig jaar na het zinken van de Hr.Ms. K XVI en haar 36-koppige bemanning » Lees verder op pagina 3 Zelfgemaakte bom is er eindelijk duidelijkheid voor de nabestaanden. Australische sportduikers vonden de onderzee- verwondt EOD’ers boot begin deze maand voor de kust van Borneo. Katja Boonstra-Blom is dochter van een van de 36 opvarenden en zocht zelf actief mee. Ze is opgelucht dat het graf van haar vader eindelijk is gevon- VOOrsCHOTen De 44-jarige den. “We zijn de bemanningsleden na al die jaren van vermissing nooit vergeten.” sergeant-majoor van de landmacht die afgelopen zondag gewond raakte door een zelfgemaakt explosief, moet door het opgelopen letsel zijn rechterhand missen. Een 41-jarige ranggenoot van de luchtmacht is inmiddels uit het ziekenhuis Landmacht onder nieuwe leiding ontslagen. De specialisten waren in de gemeente Voorschoten net klaar met de demontage van een bom aan een flitspaal. ’T Harde Luitenant-generaal Mart de Kruif is dinsdag aangetre- Binnen de EOD ontstond grote beroe- den als de nieuwe Commandant Landstrijdkrachten. Hij nam het ring nadat bekend werd dat twee directe collega’s bij het incident gewond waren bevel over van ranggenoot Rob Bertholee die sinds maart 2008 de geraakt. Veel specialisten betuigden hun scepter zwaaide en de krijgsmacht met leeftijdsontslag verlaat. De steun aan zowel de slachtoffers als hun ceremoniële overdacht vond plaats op de legerplaats bij Oldebroek naasten en aan de betrokken politie- agent. -

2008 Highlights. 1

2008 Highlights. 1 IMPRESSUM INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Grußwort Vor 50 Jahren Herausgeber Ministerpräsident Oettinger 3 Im Baumwoll-Badeanzug 52 Internationale Sport-Korrespondenz (ISK) ISK Vor 50 Jahren Wahl ist der Kick 5 Studentin im Abendkleid 54 Objektleitung VDS Hightech Beate Dobbratz, Thomas R. Wolf Sporthöhepunkte 2008 7 Tempo dank FES 56–57 Galerie Mountainbike Redaktion Rückblick in Bilder 8–13 Frontfrau Sabine 58 Sparkassenpreis Tischtennis Sven Heuer, Jürgen C. Braun Auszeichnung für Vorbilder 14 Näher an China 60 Peking Formel 1 Konzeption und Herstellung Keine Sonne, Mond, Sterne 16–18 Vettel kommt 62 PRC Werbe-GmbH, Filderstadt Olympia Motorsport Starker Mann 20 Schneider geht 64 Sponsoring und Anzeigen Olympia Eis (I) Lifestyle Sport Marketing GmbH, Filderstadt Hockey 22 Annis Kufen 66–67 Olympia Eis (II) Schwimm-Königinnen 24 Neue Ästhetik 68 Fotos Olympia Eis (III) dpa Picture-Alliance GmbH Hauteng 26 Bob mit 150 km/h 70 Jürgen Burkhardt Olympia Biathlon Vitesse Kärcher GmbH Außenstelle Hongkong 28–29 Goldene Skijägerinnen 72 Olympia Fechten Augenklick Bilddatenbank Turnen 30 Die chinesische Deutsche 74–75 mit den Fotografen Paralympics Ausblick Neue Dimensionen 32–33 Highlife 2009 76 und Agenturen: Olympia Glosse Pressefoto Dieter Baumann Waterworld 34 Der gepflegte Mann 78–79 Sportphoto by Laci Perenyi Olympia Rudern Pressefoto Rauchensteiner Auf Wiedersehen 36 Havarie 80 Hennes Roth ZDF Leichtathletik Sampics Photographie Bewegende Szenen 38 Abgetaucht 82–83 Fußball Triathlon Löws Anspruchsdenken 40–41 Frodenos Alltag 84 Fußball Breitensport Karikatur EM-Gewitter 42 Aus dem Profi-Schatten 86–87 Sepp Buchegger Schiedsrichter Weltwahl Gestatten, Dr. Merk 44–45 Bolt und Isinbajewa 88–89 Fußball Geschichte Ho-Ho-Hoffenheim 46 Wahl seit 1947 90–94 Sporthilfe Resultate 2008 Juniorsportler 48 Das Sportjahr in Zahlen 96–115 Hall of Fame Gala Deutsche Legenden 50–51 Die Ehrengäste 116 –119 3 GRUSSwoRT Zur 62. -

D I P L O M O V Á P R Á C E

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA FAKULTA SPORTOVNÍCH STUDIÍ KATEDRA GYMNASTIKY A ÚPOLŮ D I P L O M O V Á P R Á C E BRNO 2009 PETR SUPARIČ - 1 MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Fakulta sportovních studií Katedra gymnastiky a úpolů Historie Olympijských her v Judo D I P L O M O V Á P R Á C E Vedoucí diplomové práce: Vypracoval: Bc. Petr Suparič PhDr. Bc. Zdenko Reguli, Ph.D. Brno, 2009 - 2 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci na téma :“ Historie Olympijských her v Judo“vypracoval samostatně a na základě literatury a pramenů uvedených v Seznamu použité literatury. V Brně, dne 17.4.2009 Podpis diplomanta: Bc. Petr Suparič - 3 Děkuji PhDr. Bc. Zdenku Reguli, Ph.D. za cenné rady a metodické vedení při řešení diplomového úkolu. - 4 OBSAH ÚVOD, CÍL PRÁCE, METODIKA A FAKTA ..................................... 7 1. LITERÁRNÍ PŘEHLED ........................................................................... 9 1.1 CHARAKTERISTIKA OLYMPIJSKÝCH HER ......................................... 9 1.1.1 Historie vzniku olympijských her ........................................................ 9 1.1.2 Historie vzniku českého olympijského výboru .................................. 12 1.1.3 Olympijské hry a ženy ....................................................................... 13 1.2 CHARAKTERISTIKA A POPIS JUDO .................................................... 15 1.2.1 Historie judo – jeho vznik a zakladatelé ............................................ 15 1.2.2 Popis judo, princip sportu ................................................................. -

Lezing Mark Huizinga Bij CISM Tunis

HIGH LEVEL SPORT IN THE NETHERLANDS - TOP LEVEL SPORTS SELECTION Captain Mark HUIZINGA, the Netherlands “Sports are a part of the Defence organisation. Physical training and sports form the basis for combat-ready armed forces. Physical fitness is a basic requirement for all military personnel. Top-level sportsmen and women support this message. Preparation, focus, discipline, teamwork, strategy and tactics are all required in order to perform at the highest level. Perseverance, physical strength and mental fitness are also essential. That is true for the military profession as well as in the sports arena. Sports are a part of the Defence organisation. The athletes of the Defence Top-level Sports Selection are people with a mission, in the same way as the Defence organisation as a whole has a mission. The members of our top-level sports selection are all outstanding athletes, who have been in action during the Olympic Games in Athens, or who are working towards the Games in Beijing. Their sporting efforts and public appearances help familiarise a wider public with both the identity and the tasks of the Dutch armed forces”. Ladies and gentlemen, This is a quote from Cees van der Knaap, the Dutch State Secretary for Defence. It implies that the Netherlands Defence Forces Top-level Sports Selection is a proper entity, that is referred to in an actual Policy Memorandum The Defence Top-level Sports Selection has both the formal and the informal support of the political leadership of the Ministry. In the twentieth century, a steady stream of conscripted young sportsmen entered the armed forces, but that intake came to an end when conscription was suspended and the armed forces turned professional. -

Most Medals 5 Ryoko Tamura-Tani JPN 1992/1996/2000/2004/2008 4 Angelo Parisi FRA/GBR 1972/1980/1984 4 Driulys González CUB 1992

JUDO Most Medals 5 Ryoko Tamura-Tani JPN 1992/1996/2000/2004/2008 4 Angelo Parisi FRA/GBR 1972/1980/1984 4 Driulys González CUB 1992/1996/2000/2004 3 Angelo Parisi FRA 1980/1984 3 David Douillet FRA 1992/1996/2000 3 Amarilys Savón CUB 1992/1996/2004 3 Tadahiro Nomura JPN 1996/2000/2004 3 Kye Sun-Hui PRK 1996/2000/2004 3 Mark Huizinga NED 1996/2000/2004 3 Edith Bosch NED 2004/2008/2012 2 Jimmy Pedro USA 1996/2004 Most Gold Medals 3 Tadahiro Nomura JPN 1996/2000/2004 2 Wim Ruska NED 1972 2 Hitoshi Saito JPN 1984/1988 2 Peter Seisenbacher AUT 1984/1988 2 Waldemar Legień POL 1988/1992 2 David Douillet FRA 1996/2000 2 Ryoko Tamura-Tani JPN 2000/2004 2 Ayumi Tanimoto JPN 2004/2008 2 Masato Uchishiba JPN 2004/2008 2 Masae Ueno JPN 2004/2008 2 Xian Dongmei CHN 2004/2008 Most Silver Medals 2 Angelo Parisi FRA/GBR 1972/1980/1984 2 Angelo Parisi FRA 1980/1984 2 Neil Adams GBR 1980/1984 2 Estela Rodríguez CUB 1992/1996 2 Yoko Tanabe JPN 1992/1996 2 Ryoko Tamura-Tani JPN 1992/1996/2000/2004/2008 2 Daima Beltrán CUB 2000/2004 2 Yanet Bermoy CUB 2008/2012 2 Jimmy Pedro USA 1996/2004 Most Bronze Medals 3 Amarilys Savón CUB 1992/1996/2004 2 15 athletes tied with 2 Most Years Winning Medals 5 Ryoko Tamura-Tani JPN 1992/1996/2000/2004/2008 4 Driulys González CUB 1992/1996/2000/2004 3 Angelo Parisi FRA/GBR 1972/1980/1984 3 David Douillet FRA 1992/1996/2000 3 Amarilys Savón CUB 1992/1996/2004 3 Tadahiro Nomura JPN 1996/2000/2004 3 Kye Sun-Hui PRK 1996/2000/2004 3 Mark Huizinga NED 1996/2000/2004 3 Edith Bosch NED 2004/2008/2012 2 Jimmy Pedro USA 1996/2004 -

Media Representations of Muslim Football Players in France

View from the Press Box: Media Representations of Muslim Football Players in France Madison Kunkel International Affairs Honors Spring 2021 Defense Copy Defense Date: April 2, 2021 Committee: Thesis Advisor: Dr. Thomas Zeiler, Department of International Affairs IAFS Honors Council Representative: Dr. Doug Snyder, College of Arts and Sciences Honors Program Second Reader: Dr. Elisabeth Arnould-Bloomfield, Department of French and Italian Abstract This thesis analyzes the convergence of the positive sentiments around the multiracial and multi-religious French football team and the pervasive anti-Muslim sentiment in French society by conducting research on portrayals of Muslim football players on the French national football team over a span of twenty-one years. Conclusions were drawn from a content analysis of newspaper articles from four French publications—Le Monde, Le Figaro, L’Humanité, and La Croix—and supplemented by a questionnaire answered by over fifty French residents. The content analysis and questionnaire provided evidence for multiple patterns of representation. Minority players were subjected to portrayals of symbols of integration, notional acceptance, and brawn versus brains, Orientalist, and clash of civilizations rhetoric, while the team as a whole was often praised as a symbol of the multicultural quality of French society. The presence of these patterns of representation in both the media and questionnaire show that these racist discourses operate in French society and help explain why even second and third generation immigrants are not accepted as French. Additionally, these discourses and the writings about the French team as a symbol of multiculturalism suggest that this symbolism is superficial and only meant to appear as the acceptance of diversity. -

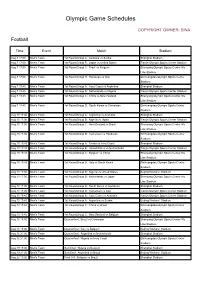

Download Schedule(PDF)

Olympic Game Schedules COPYRIGHT OWNER: SINA Football Time Event Match Stadium Aug.7 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup A : Australia vs Serbia Shanghai Stadium Aug.7 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup B : Japan vs United States Tianjin Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.7 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup C : Brazil vs Belgium Shenyang Olympic Sports Center Wu Lihe Stadium Aug.7 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup D : Honduras vs Italy Qinhuangdao Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.7 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup A : Ivory Coast vs Argentina Shanghai Stadium Aug.7 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup B : Netherlands vs Nigeria Tianjin Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.7 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup C : China vs New Zealand Shenyang Olympic Sports Center Wu Lihe Stadium Aug.7 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup D : South Korea vs Cameroon Qinhuangdao Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.10 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup A : Argentina vs Australia Shanghai Stadium Aug.10 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup B : Nigeria vs Japan Tianjin Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.10 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup C : New Zealand vs Brazil Shenyang Olympic Sports Center Wu Lihe Stadium Aug.10 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup D : Cameroon vs Honduras Qinhuangdao Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.10 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup A : Serbia vs Ivory Coast Shanghai Stadium Aug.10 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup B : United States vs Netherlands Tianjin Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.10 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup C : Belgium vs China Shenyang Olympic Sports Center Wu -

Highlights 2004

2004 Highlights. 1 IMPRESSUM INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Herausgeber Grußwort Radsport Internationale Sport-Korrespondenz (ISK) Bundesinnenminister Otto Schilyy ...... 3 Tour totall................................. 44–46 ISK ZDF Objektleitung 300 Wahlvorschlägee ........................ 5 Traditioneller Abschlusss ................. 48 Beate Dobbratz, Thomas R. Wolf VDS Formel 1 Vor allen Dingen Kommunikationn ...... 7 Schumis Mannschaftt ............... 50–51 Redaktion Sportjahr Handball Matthias Huthmacher, Sven Heuer Von Januar bis Dezemberr ........... 8–11 Abschiedstränenn........................... 52 Eliteschulen Leichtathletik Konzeption und Herstellung Sportförderer DSGVV ....................... 12 Achselzuckenn ................................ 54 PRC Werbe-GmbH, Filderstadt Highlights Schwimmen Athener Bilderbogenn.................14–15 Abgetauchtt.................................... 55 Sponsoring Olympia I Schwimmen Lifestyle Sport Marketing GmbH, Filderstadt Hoch auf Hockeyy ......................16–18 Ironwomann .................................... 56 Olympia II Doping Anzeigen Goldwasserr ............................. 20–21 Not cleann ................................ 58–59 Lifestyle Sport Marketing GmbH, Filderstadt Olympia III Sportpolitik Stuttgart Friends, Filderstadt 1400 TV-Stundenn........................... 22 Fusion DSB-NOKK......................60–61 Olympia IV Weltsportler Fotos Keine Chaos-Spielee ....................... 24 Federer ganz souveränn ................... 65 dpa Glosse Sporthilfe Jürgen Burkhardt Männersynchronschwimmen?? -

Judo No1 Mai 12

Mai 2012 Judo News Alle Informationen zum Judosport in Gotha ab jetzt neu im Judo No1. JUDO NO1 Internationales Flair auf der Judomatte. Messe-Cup & ega- Pokal in Erfurt 15. INTERNATIONALER MESSE-CUP UND EGA-POKAL 1000 Judoka aus 11 Nationen und 180 Vereinen ganz Deutschlands kämpften am 12./13. Mai in Erfurts Leichtathletikhalle. Die Kämpfer vom FSV 1950 Gotha und der SSG Wechmar blieben medaillenlos. Leer ausgegangen sind die Judoka der Erfolge. Beim Internationalen ega-Pokal der SSG Wechmar und des FSV 1950 Gotha am Altersklasse U13 konnten sowohl die Gothaer, vergangenen Wochenende in Erfurt. Am als auch die Wechmarer Judoka keinen Kampf Samstag konnte beim Internationalen Messe- gewinnen. Insgesamt nahmen an beiden Cup lediglich Pio Wittek zwei Kämpfe hochkarätigen Wettkämpfen knapp 1000 gewinnen. Im Kampf um den Poolsieg Kämpfer aus 11 Nationen und 180 Vereinen scheiterte er knapp am Berliner Florian Dufour ganz Deutschlands teil. Beim Messe-Cup und verlor anschließend seinen ersten konnte Maxime Brausewetter vom Erfurter Trostrundenkampf. Das war das vorzeitige Aus Judo-Club (EJC) für Thüringen eine für den Kämpfer aus Wechmar. Victoria Goldmedaille holen. Weiterhin gab es Hesselbach und Fabian Meyer (beide FSV Bronzemedaillen für Julien Mertens (EJC) und Gotha) mussten sich trotz teilweise guter Frederike Fiedel (Mattenteufel). Kämpfe ebenfalls in der Trostrunde geschlagen Dzohar Bekbusarow (PSV Erfurt) konnte geben. Dabei sah Fabian Meyer gegen seinen beim ega-Pokal den 1. Platz, Tom Gut vorbereitet in den Kampf? ungarischen Gegner Inotai gar nicht schlecht Blechschmied (JSC Stotternheim) den 2. Platz Eine gute Vorbereitung auf den aus. SeIbst im Golden Score konnte der Ungar belegen. -

OLÍMPICOS a HISTÓRIA DO SÃO PAULO NOS JOGOS Apesar Do Sobrenome Futebol Clube, O São Paulo É Um Clube Com Longa Tradição Poliesportiva

OLÍMPICOS A HISTÓRIA DO SÃO PAULO NOS JOGOS Apesar do sobrenome Futebol Clube, o São Paulo é um clube com longa tradição poliesportiva. Além das inúmeras conquistas nos gramados, tanto no masculino quanto no feminino, o Tricolor já contou com vitórias em diversas modalidades esportivas, tais como futsal, voleibol, basquete, rúgbi... até mesmo esgrima, remo e polo aquático. Mas especialmente em dois esportes, além do futebol, o Tricolor é historicamente uma verdadeira potência olímpica nacional. No atletismo, o clube é hexacampeão do Troféu Brasil, tetradecampeão paulista, decacampeão da Corrida de São Silvestre entre clubes e tetracampeão de modo individual, sem contar as conquistas e marcas mundiais, pan-americanas e sul-americanas. No boxe, três conquistas mundiais (uma delas, unificada), vários títulos pan-americanos e sul-americanos, além de 21 campeonatos estaduais e inúmeros Torneios dos Campeões, Luvas de Ouro e Forja dos Campeões. Mais recentemente, juntou-se a essa trinca esportiva também o judô, que, com grandes atletas, trouxe várias vitórias para os são-paulinos. E foram nestas quatro modalidades: futebol, atletismo, boxe e judô, que o São Paulo Futebol Clube, desde 1948, enviou 58 atletas (63 participações) e cinco treinadores (em oito participações) para os Jogos Olímpicos. Somente em 1972 e 1980, o Tricolor não contou com nenhum atleta representando o clube nas Olimpíadas. E a relação poderia ser ainda maior. Quando o São Paulo esteve no auge de sua “poliesportividade”, no início dos anos 1940, competindo em alto nível em dezenas de modalidades, com atletas brasileiros e estrangeiros, não foram realizados os Jogos Olímpicos das XII e XIII Olimpíadas (1940 e 1944) devido à II Guerra Mundial. -

Kiwanis International Page 1 of 73 Time 9:53:25AM District Registration Listing MTG9004

Date 02/11/2011 Kiwanis International Page 1 of 73 Time 9:53:25AM District Registration Listing MTG9004 N = New Registration, C = Cancelled Registrant, P = Primary Meeting: 2011 Convention Delegate, A = Alternate Delegate, L = At Large Delegate K01 Alabama Reg Division Club Name State Del New Registrant Name Can Guest Gst Can Division 1 Huntsville AL Anderson, Sherwood H Anderson, Susan M Division 2 Cullman AL Carter, Matthew K Decatur AL Stewart, Patrice Florence AL Broder, Michael 1 Division 3 Hamilton AL West, Alan C Ann Division 4 Tuscaloosa AL Copeland, Gary A Division 5 Homewood-Mountain Brook AL Black, Colean T Manasco, Patricia A Division 6 Metropolitan Birmingham AL Bradley, Owen A Division 7 Anniston AL Cleckler, Dan Faye Gadsden AL Driskill, Tameria Shaye Selman, Dr Glenda C Selman, Philip L Division 8 Wedowee AL Lanier, Jo Ann B Lanier Jr, Sidney L Division 9 Capital City, Montgomery AL Gentry, W Dale Jackie Good Morning, Montgomery AL Buehler, Bruce A Mary Montgomery AL Dunman, Russell S Norman, Keith B Screws, Andrea Division 10 Auburn AL Halverson, Eric Tallassee AL Humphries, Edward V Humphries, Olivia G Division 11 Troy AL Williams, Joel L Williams, Teri Division 12 Andalusia AL Kelley, Gwendolyn B Thomas, Steve Division 13 Daphne-Spanish Fort AL Gifford, John Gifford, Marcia Totals: Registrants: 30 Guests: 5 Date 02/11/2011 Kiwanis International Page 2 of 73 Time 9:53:25AM District Registration Listing MTG9004 N = New Registration, C = Cancelled Registrant, P = Primary Meeting: 2011 Convention Delegate, A = Alternate