The Show Goes On: Adaptive Reuse and the Preservation of Opera Houses in North Dakota

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Don Giovanni Sweeney Todd

FALL 2019 OPERA SEASON B R AVO Don Giovanni OCTOBER 19-27, 2019 Sweeney Todd NOVEMBER 16-24, 2019 2019 Fall Opera Season Sponsor e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. Choose one from each course: FIRST COURSE Caesar Side Salad Chef’s Soup of the Day e Whitney Duet MAIN COURSE Grilled Lamb Chops Lake Superior White sh Pan Roasted “Brick” Chicken Sautéed Gnocchi View current menus DESSERT and reserve online at Chocolate Mousse or www.thewhitney.com Mixed Berry Sorbet with Fresh Berries or call 313-832-5700 $39.95 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. -

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

City of Woodstock Office of the City Manager Phone (815) 338-4301 Fax (815) 334-2269 [email protected] 121 W

City of Woodstock Office of the City Manager Phone (815) 338-4301 Fax (815) 334-2269 [email protected] www.woodstockil.gov 121 W. Calhoun Street Roscoe C. Stelford III Woodstock, Illinois 60098 City Manager WOODSTOCK CITY COUNCIL City Council Chambers March 17, 2020 7:00 p.m. Individuals wishing to address the City Council are invited to come forward to the podium and be recognized by the Mayor; provide their name and address for purposes of the record, if willing to do so; and make whatever appropriate comments they would like. The complete City Council packet is available at the Woodstock City Hall, viewed online at the Woodstock Public Library, and via the City Council link on the City’s website, www.woodstockil.gov. For further information, please contact the Office of the City Manager at 815-338-4301 or [email protected]. The proceedings of the City Council meeting are live streamed on the City of Woodstock’s website, www.woodstockil.gov. Recordings can be viewed, after the meeting date, on the website. I. CALL TO ORDER II. ROLL CALL III. FLOOR DISCUSSION A. Proclamation: Music in Our Schools Month B. Presentation: Real Woodstock’s Year in Review Anyone wishing to address the Council on an item not already on the agenda may do so at this time. C. Public Comments D. Council Comments IV. CONSENT AGENDA: (NOTE: Items under the consent calendar are acted upon in a single motion. There is no separate discussion of these items prior to the Council vote unless: 1) a Council Member requests that an item be removed from the calendar for separate action, or 2) a citizen requests an item be removed and this request is, in turn, proposed by a member of the City Council for separate action.) Woodstock City Council March 17, 2020 Page 2 A. -

SOH-Annual-Report-2016-2017.Pdf

Annual Report Sydney Opera House Financial Year 2016-17 Contents Sydney Opera House Annual Report 2016-17 01 About Us Our History 05 Who We Are 08 Vision, Mission and Values 12 Highlights 14 Awards 20 Chairman’s Message 22 CEO’s Message 26 02 The Year’s Activity Experiences 37 Performing Arts 37 Visitor Experience 64 Partners and Supporters 69 The Building 73 Building Renewal 73 Other Projects 76 Team and Culture 78 Renewal – Engagement with First Nations People, Arts and Culture 78 – Access 81 – Sustainability 82 People and Capability 85 – Staf and Brand 85 – Digital Transformation 88 – Digital Reach and Revenue 91 Safety, Security and Risk 92 – Safety, Health and Wellbeing 92 – Security and Risk 92 Organisation Chart 94 Executive Team 95 Corporate Governance 100 03 Financials and Reporting Financial Overview 111 Sydney Opera House Financial Statements 118 Sydney Opera House Trust Staf Agency Financial Statements 186 Government Reporting 221 04 Acknowledgements and Contact Our Donors 267 Contact Information 276 Trademarks 279 Index 280 Our Partners 282 03 About Us 01 Our History Stage 1 Renewal works begin in the Joan 2017 Sutherland Theatre, with $70 million of building projects to replace critical end-of-life theatre systems and improve conditions for audiences, artists and staf. Badu Gili, a daily celebration of First Nations culture and history, is launched, projecting the work of fve eminent First Nations artists from across Australia and the Torres Strait on to the Bennelong sail. Launch of fourth Reconciliation Action Plan and third Environmental Sustainability Plan. The Vehicle Access and Pedestrian Safety 2016 project, the biggest construction project undertaken since the Opera House opened, is completed; the new underground loading dock enables the Forecourt to become largely vehicle-free. -

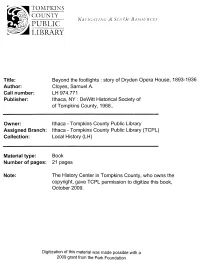

Beyond Footlights.Pdf

TOMPKINS COUNTY Navigating A Sua Or Resources PUBLIC LIBRARY Title: Beyond the footlights : story of Dryden Opera House, 1893-1936, Author: Cloyes, Samuel A. Call number: LH 974.771 Publisher: Ithaca, NY : DeWitt Historical Society of of Tompkins County, 1968., Owner: Ithaca - Tompkins County Public Library Assigned Branch: Ithaca - Tompkins County Public Library (TCPL) Collection: Local History (LH) Material type: Book Number of pages: 21 pages Note: The History Center in Tompkins County, who owns the copyright, gave TCPL permission to digitize this book, October 2009. Digitization of this material was made possible with a 2009 grant from the Park Foundation LH rt -i 97U..771 Cloyes, Samuel Beyond the footlights . LH 974.771 Cloyes Cloyes, Samuel A. Beyond the footlights : story of Dryden Opera House, 1893-1936. DO NOT TAKE CARDS FROM POCKET to::?::i:i3 cou:ity public LIBRARY Xtfc**t N.Y, View of the old Dryden Opera House on Library Street. Built in 1893. First Professional play presented on its stage was on January 1, 1894 by the Ella Fontainbleau Dramatic Company. House shown next to theater was home of Dr. Jennings, followed by the residence of Theon Johnson . Beyond the Footlights Story of Dryden Opera House 1893-1936 By SAMUEL A. CLOYES Curator, DeWitt Historical Society 1968 DeWITT HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF TOMPKINS COUNTY, INC. Ithaca, N. Y. 14850 PUBLIC LIBRARY TOMPKINS COUNTY Contents In the Beginning 1 The Curtain Rises 5 Rules and Regulations 7 A Bouquet Is Tossed 8 Home-Talent Players Take to Stage 9 Opera House Encore 11 There's Music in the Air 12 Time Marches On 13 A Benevolent Performance 14 Swing Your Partners 15 End of the Gay '90's 16 Eastern Star Shines 16 Gentlemen, Take Your Seats 17 Shadows Start To Fall 18 The Curtain Descends 18 The Grand Finale 20 Fires Aftermath 21 Acknowledgments This story does not pretend to be a complete history of the Dryden Opera House, but rather an effort to collect and put into preservable form some record of the service it rendered Dryden neighborhood as an entertainment center. -

Jeff Rupert Saxophone Master Class

Jeff Rupert Saxophone Master Class I Saxophone Assembly and maintenance Holding the instrument. The neck and mouthpiece assembly. Checking key mechanisms. Checking for leaks, and clogged vents. Maintaining the lacquer. Setting the instrument down. II Posture The Back and neck. Legs and knees. III Breathing and Breath flow Inhaling. Exhaling. Breath solfège IV The Oral Cavity and the Larynx. V Embouchures for playing the saxophone. Variance in embouchure technique. The embouchure and breathing. VI Daily Routines for practicing the saxophone. Daily routines and rituals. Playing the mouthpiece. Playing the mouthpiece with the neck. Overtone exercises. VII Articulation Single tonguing. Doodle tonguing. Alternate articulations specific to jazz. Double tonguing. VIII Practice patterns for scales. Scales and Arpeggios Major, minor (dorian, natural minor, ascending jazz melodic minor, harmonic minor) and diminished. Resources for jazz scales. IX Equipment Different horns. Mouthpieces. Reeds. Ligatures. Neckstraps. X Resources for saxophonists Recordings. Web resources. Books and educational CD's and DVD's. Saxophonists in jazz and pop music. XI Conclusion. ©2009 Rupe Music Publishing 001 saxophone master class, Jeff Rupert pg2 I Saxophone Assembly and maintenance Neck and mouthpiece assembly: Putting the saxophone together is something we've all been doing since day one. It may seem trite to even address assembly of the instrument, but its been a common flaw not to develop good habits. I've seen broken mouthpieces, bent rods and necks several times from seasoned professionals who should have known better! This is precisely why its important to develop good habits when putting your instrument together. Prior to putting the mouthpiece on the neck, make certain that the cork is lubricated. -

Santa Fe New Mexican, 04-27-1907 New Mexican Printing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 4-27-1907 Santa Fe New Mexican, 04-27-1907 New Mexican Printing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news Recommended Citation New Mexican Printing Company. "Santa Fe New Mexican, 04-27-1907." (1907). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news/6610 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. R1R 11 ANTA --IL NEW MEXI6AN VOL. 44. SANTA EE, N. M SATURDAY, APRIL 27, 1907. NO. 59. ATHLETES GATHER DOUBLE TRAGEDY MURDERER EILIO AT PHILADELPHIA TAFT GIVEN OVER LAND DEAL Mil To Participate in Annual Carnival of S. B. Owens and B. S. Turbyfield Vic- Field Sports on Franklin Field tims of Fatal Feud Owens' BREAKS JAIL WELCOME IS Son COLLAPSES 1,200 Present. Wl mm Gets Quick Vengeance. Philadelphia, Pa., April 27. More Iloswell, N. M., April than twelve hundred athletes are as- reached here-yesterda- afternoon of From Lin- sembled here ready for this after Cincinnati Receives Deliberated on a double tragedy which occu.red the At Baltimore Six- Jury ' Escapes noon's carnival of relay races and day previous near Alan Reed, Texas, coln field sports on Franklin Field. The War Verdict Twenty-On- e in which S. B. Owens was killed by! teen Workmen County collection of contestants is one of the Secretary B. -

Ella Fitzgerald from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Ella Fitzgerald From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Background information Birth name Ella Jane Fitzgerald Born April 25, 1917 Newport News, Virginia, United States Died June 15, 1996 (aged 79) Beverly Hills, California, United States Genres Swing, bebop, traditional pop, vocal jazz Occupation(s) Singer, actress Instruments Vocals Years active 1934–1993 Labels Capitol, Decca, Pablo, Reprise, Verve, Brunswick, HMV Website ellafitzgerald.com Ella Jane Fitzgerald (April 25, 1917 – June 15, 1996) was an American jazz singer often referred to as the First Lady of Song, Queen of Jazz, and Lady Ella. She was noted for her purity of tone, impeccable diction, phrasing and intonation, and a "horn-like" improvisational ability, particularly in her scat singing. After tumultuous teenage years, Fitzgerald found stability in musical success with performances on many stages in the Harlem area, including her rendition of the nursery rhyme "A-Tisket, A-Tasket" that helped boost her to fame. In 1942, Fitzgerald left the amateur performances behind, signed a deal with Decca Records, and started her solo career by redefining the art of scat singing. It was not until her manager, Norman Granz, built Verve Records based on her vocal abilities that she recorded some of her more widely noted works. Under this label, Fitzgerald focused more on singing than scatting, providing perhaps her most career-defining works in her interpretation of the Great American Songbook. While Fitzgerald appeared in movies and as guests on popular television shows in the second half of the twentieth century, her musical collaborations with Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Bill Kenny and the Ink Spots were some of her most notable acts outside of her solo career. -

Instead Draws Upon a Much More Generic Sort of Free-Jazz Tenor Saxophone Musical Vocabulary

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. BOBBY HUTCHERSON NEA Jazz Master (2010) Interviewee: Bobby Hutcherson (January 27, 1941 – August 15, 2016) with his wife Rosemary Hutcherson Interviewer: Anthony Brown with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: December 8-9, 2010 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 60 pp. Brown: Today is December 8th, 2010. Bobby Hutcherson: Oooo, December 8th. Brown: This is the Smithsonian NEA Jazz Oral History interview with Bobby Hutcherson in his home in Montero, California. Good afternoon, Bobby. Hutcherson: Good afternoon. Brown: It’s indeed a pleasure to be here, be in your home and be able to talk to you, one of my heroes for so many years, a fellow Californian. If we could just start by you stating your full name at birth and your birth place and birth date, please. Hutcherson: Robert Howard Hutcherson. I was born January 27, 1941, in Los Angeles, but I grew up in Pasadena, California. Brown: But you say you were born in Los Angeles. Hutcherson: Um-hmm. Brown: Is that where your parents were living at the time of your birth? For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 1 Hutcherson: No. It was – they were living in Pasadena, but a lot of my relatives were living in Los Angeles, Watts and stuff like that. So it worked out, because they could be there. My mom had me very late in her life, in those days, and so it was better for my father to take my mother to the Los Angeles hospital, because he was – his work, he was a bricklayer. -

Jazz Library (Song Listings)

Music 932 songs, 3.7 days, 10.39 GB Name Time Album Artist Afrodisia 5:06 Afro-Cuban Kenny Dorham Lotus Flower 4:17 Afro-Cuban Kenny Dorham Minor's Holiday 4:28 Afro-Cuban Kenny Dorham Basheer's Dream 5:03 Afro-Cuban Kenny Dorham K.D.'s Motion 5:29 Afro-Cuban Kenny Dorham The Villa 5:24 Afro-Cuban Kenny Dorham Venita's Dance 5:22 Afro-Cuban Kenny Dorham Echo Of Spring (a.k.a. K.D.'s Cab Ride) 6:12 Afro-Cuban Kenny Dorham Minor's Holiday [Alternate Take] 4:24 Afro-Cuban Kenny Dorham Bouncing With Bud 3:05 The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 1 Bud Powell Wail 3:06 The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 1 Bud Powell Dance Of The Infidels 2:54 The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 1 Bud Powell 52nd Street Theme 2:50 The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 1 Bud Powell You Go To My Head 3:15 The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 1 Bud Powell Ornithology 2:23 The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 1 Bud Powell Bouncing With Bud [Alternate Take 1] 3:06 The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 1 Bud Powell Bouncing With Bud [Alternate Take 2] 3:16 The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 1 Bud Powell Wail [Alternate Take] 2:42 The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 1 Bud Powell Dance Of The Infidels [Alternate Take] 2:51 The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 1 Bud Powell Ornithology [Alternate Take] 3:12 The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 1 Bud Powell Un Poco Loco 4:46 The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. -

Loop the Loop Worksheets

‘LOOP THE LOOP’ Music Educational Resource by N. Peterson Welcome to the “House” Sydney Opera House is one of the indisputable masterpieces of human creativity and has long been a place for learning and sharing knowledge. Tubowgule: where the knowledge waters meet The history of performance at Bennelong Point stretches back thousands of years. The land on which Sydney Opera House stands was known to its traditional custodians, the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation, as Tubowgule, meaning "where the knowledge waters meet." A stream carried fresh water down from what is now Pitt Street to the cove near Tubowgule, a rock promontory that at high tide became an island. The mixing of fresh and salt waters formed a perfect fishing ground. Middens of shells were a testament to Tubowgule's long history as a place where the Gadigal gathered, feasted, sung, danced and told stories. Did You Know…? 1. More than 8.2 million people visit the Opera House every year. 2. Sydney Opera House is cooled using seawater taken directly from the harbour. The system circulates cold water from the harbour through 35 kilometres of pipes to power both the heating and air conditioning in the building. 3. Sydney Opera House was opened by Queen Elizabeth II on 20th October, 1973. She has since visited four times, most recently in 2006. 4. The Sydney Opera House Digital Creative Learning program allows students from all over the world to access the Sydney Opera House and learn about its history and culture, while also developing skills in literacy, drama and creative writing. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least.