Teaching and Learning Jazz Trombone Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Don Giovanni Sweeney Todd

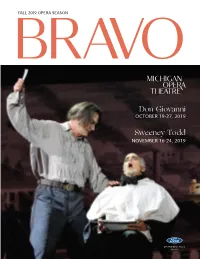

FALL 2019 OPERA SEASON B R AVO Don Giovanni OCTOBER 19-27, 2019 Sweeney Todd NOVEMBER 16-24, 2019 2019 Fall Opera Season Sponsor e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. Choose one from each course: FIRST COURSE Caesar Side Salad Chef’s Soup of the Day e Whitney Duet MAIN COURSE Grilled Lamb Chops Lake Superior White sh Pan Roasted “Brick” Chicken Sautéed Gnocchi View current menus DESSERT and reserve online at Chocolate Mousse or www.thewhitney.com Mixed Berry Sorbet with Fresh Berries or call 313-832-5700 $39.95 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. -

Applied Anatomy in Music: Body Mapping for Trumpeters

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones May 2016 Applied Anatomy in Music: Body Mapping for Trumpeters Micah Holt University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Music Commons Repository Citation Holt, Micah, "Applied Anatomy in Music: Body Mapping for Trumpeters" (2016). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2682. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/9112082 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APPLIED ANATOMY IN MUSIC: BODY MAPPING FOR TRUMPETERS By Micah N. Holt Bachelor of Arts--Music University of Northern Colorado 2010 Master of Music University of Louisville 2012 A doctoral project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2016 Dissertation Approval The Graduate College The University of Nevada, Las Vegas April 24, 2016 This dissertation prepared by Micah N. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Duke Ellington Kyle Etges Signature Recordings Cottontail

Duke Ellington Kyle Etges Signature Recordings Cottontail. Cottontail stands as a fine example of Ellington’s “Blanton-Webster” years, where the band was at its peak in performance and popularity. The “Blanton-Webster” moniker refers to bassist Jimmy Blanton and tenor saxophonist Ben Webster, who recorded Cottontail on May 4th, 1940 alongside Johnny Hodges, Barney Bigard, Chauncey Haughton, and Harry Carney on saxophone; Cootie Williams, Wallace Jones, and Ray Nance on trumpet; Rex Stewart on cornet; Juan Tizol, Joe Nanton, and Lawrence Brown on trombone; Fred Guy on guitar, Duke on piano, and Sonny Greer on drums. John Hasse, author of The Life and Genius of Duke Ellington, states that Cottontail “opened a window on the future, predicting elements to come in jazz.” Indeed, Jimmy Blanton’s driving quarter-note feel throughout the piece predicts a collective gravitation away from the traditional two feel amongst modern bassists. Webster’s solo on this record is so iconic that audiences would insist on note-for-note renditions of it in live performances. Even now, it stands as a testament to Webster’s mastery of expression, predicting techniques and patterns that John Coltrane would use decades later. Ellington also shows off his Harlem stride credentials in a quick solo before going into an orchestrated sax soli, one of the first of its kind. After a blaring shout chorus, the piece recalls the A section before Harry Carney caps everything off with the droning tonic. Diminuendo & Crescendo in Blue. This piece is remarkable for two reasons: Diminuendo & Crescendo in Blue exemplifies Duke’s classical influence, and his desire to write more grandiose pieces with more extended forms. -

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

Colby Alumnus Vol. 65, No. 2: Winter 1976

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Colby Alumnus Colby College Archives 1976 Colby Alumnus Vol. 65, No. 2: Winter 1976 Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/alumnus Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Colby College, "Colby Alumnus Vol. 65, No. 2: Winter 1976" (1976). Colby Alumnus. 90. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/alumnus/90 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Colby College Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Alumnus by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. The Colby Alumnus Volume 65, Number 2 Winter 1976 Published quarterly fall, winter, spring, summer by Colby College Editorial board Mark Shankland Earl H. Smith Design and production Donald E. Sanborn, Jr. Martha Freese Photography Mark Shankland Letters and inquiries should be sent to the editor, change of address notification to the alumni office Entered as second-class mail at Waterville, Maine Postmaster send form 3579 to The Colby Alumnus Colby College Waterville, Maine 04901 appraisal of the future of professions, or just in our President's Page personal arrangements for the security and well-being of ourselves and our families, we must take these changes into account and must assume that there will President Robert E. L. Strider gave the keynote address be continuing acceleration of change for all the span of to a conference of the Northeastern Industrial Devel years that most of us can foresee. opers Association recently in Portland. The conference I am surely not suggesting that this state of affairs is theme was "Survival Demands Sensitivity to Change." bad. -

Heavy Metal and Classical Literature

Lusty, “Rocking the Canon” LATCH, Vol. 6, 2013, pp. 101-138 ROCKING THE CANON: HEAVY METAL AND CLASSICAL LITERATURE By Heather L. Lusty University of Nevada, Las Vegas While metalheads around the world embrace the engaging storylines of their favorite songs, the influence of canonical literature on heavy metal musicians does not appear to have garnered much interest from the academic world. This essay considers a wide swath of canonical literature from the Bible through the Science Fiction/Fantasy trend of the 1960s and 70s and presents examples of ways in which musicians adapt historical events, myths, religious themes, and epics into their own contemporary art. I have constructed artificial categories under which to place various songs and albums, but many fit into (and may appear in) multiple categories. A few bands who heavily indulge in literary sources, like Rush and Styx, don’t quite make my own “heavy metal” category. Some bands that sit 101 Lusty, “Rocking the Canon” LATCH, Vol. 6, 2013, pp. 101-138 on the edge of rock/metal, like Scorpions and Buckcherry, do. Other examples, like Megadeth’s “Of Mice and Men,” Metallica’s “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” and Cradle of Filth’s “Nymphetamine” won’t feature at all, as the thematic inspiration is clear, but the textual connections tenuous.1 The categories constructed here are necessarily wide, but they allow for flexibility with the variety of approaches to literature and form. A segment devoted to the Bible as a source text has many pockets of variation not considered here (country music, Christian rock, Christian metal). -

Gerry Mulligan Discography

GERRY MULLIGAN DISCOGRAPHY GERRY MULLIGAN RECORDINGS, CONCERTS AND WHEREABOUTS by Gérard Dugelay, France and Kenneth Hallqvist, Sweden January 2011 Gerry Mulligan DISCOGRAPHY - Recordings, Concerts and Whereabouts by Gérard Dugelay & Kenneth Hallqvist - page No. 1 PREFACE BY GERARD DUGELAY I fell in love when I was younger I was a young jazz fan, when I discovered the music of Gerry Mulligan through a birthday gift from my father. This album was “Gerry Mulligan & Astor Piazzolla”. But it was through “Song for Strayhorn” (Carnegie Hall concert CTI album) I fell in love with the music of Gerry Mulligan. My impressions were: “How great this man is to be able to compose so nicely!, to improvise so marvellously! and to give us such feelings!” Step by step my interest for the music increased I bought regularly his albums and I became crazy from the Concert Jazz Band LPs. Then I appreciated the pianoless Quartets with Bob Brookmeyer (The Pleyel Concerts, which are easily available in France) and with Chet Baker. Just married with Danielle, I spent some days of our honey moon at Antwerp (Belgium) and I had the chance to see the Gerry Mulligan Orchestra in concert. After the concert my wife said: “During some songs I had lost you, you were with the music of Gerry Mulligan!!!” During these 30 years of travel in the music of Jeru, I bought many bootleg albums. One was very important, because it gave me a new direction in my passion: the discographical part. This was the album “Gerry Mulligan – Vol. 2, Live in Stockholm, May 1957”. -

Albert Mangelsdorff Übungsstunden Im Jazzkel- Ler Frankfurt

JAZZ-PORTRAIT unabhängig davon, dass Ten- denzen des Jazz aus dem Her- kunftsland USA nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg in Europa wie normative Ideen rezipiert wurden: »Erstens ist es nicht hier gewachsen, zweitens ist es ja eine Musik, von der man eigentlich weg wollte. Was man als Jazz-Musiker will, ist doch immer die eigene Mu- sik«, sagte er einst im Ge- spräch mit Joachim Ernst Be- rendt (in: »Ein Fenster aus Jazz«). Doch Folklore, ebenso wie seine klassische Ausbil- dung, war nur bedingt ein Thema für Albert Mangels- dorff, wie Wolfram Knauer in seinem Essay »Zum Umgang von Jazz-Musikern mit deut- scher Musiktradition« (in: »Tension«) dessen minde- stens skeptische Haltung be- schrieb. Mangelsdorff be- kannte sich ostentativ dazu, »dass die eigentlichen Ele- mente des Jazz nicht verges- sen werden«. Durch seine kritische Abgrenzung von Imitationen, nicht aber die Ablehnung der afro-amerika- nischen Tradition, und seine Hinwendung zu eigenen Ressourcen gab Albert Man- gelsdorff entscheidende und nachhaltige Impulse für die Emanzipation des europäi- Photo: Sven Thielmann schen Jazz. Eigenes entstand für ihn zunächst einzeln, und zwar durch seine legendären Albert Mangelsdorff Übungsstunden im Jazzkel- ler Frankfurt. Von diesen täg- uperlative umgaben Albert Man- ausgezeichnet, sondern er war auch stets lichen Exerzitien war Albert Mangels- gelsdorff (1928 - 2005) schon zu eine kulturell integrative Persönlichkeit. dorff »abhängig, einfach um den S Lebzeiten wie einen Nimbus. Ido- Seine respektierte Autorität wirkte Standard zu halten« für -

Paul Keller Biography – One Page

PAUL KELLER BIOGRAPHY – ONE PAGE 125 W. Willis Rd Saline, MI 48176 734-316-2665 [email protected] Since 1989, string bassist Paul Keller has led his 15-piece big band Paul Keller Orchestra to critical and popular acclaim. The PKO’s American Music Research Foundation Big Band Boogie Woogie concert was broadcast nationally on PBS throughout 2009 and 2010. The PKO’s Jazz Student Outreach Program hosted 30 school bands and over 700 student musicians in 2010. Paul is a prolific composer. In October, 2010 the Ypsilanti Symphony Orchestra premiered Paul’s five-movement symphonic composition The Ypsilanti Orchestral Jazz Suite. This major piece, written for jazz band and full symphony orchestra, celebrates Paul’s hometown of Ypsilanti, MI. The suite was received enthusiastically and was praised by community leaders as an important work of art with historical significance. Paul's magnum opus The Michigan Jazz Suite is a collection of 15 Keller compositions inspired by people, places and icons of the great state of Michigan. Featuring the Paul Keller Ensemble with titles like Big Mac, and Soo’s Blues, The Michigan Jazz Suite won the Detroit Music Award for Best Jazz Recording of 2008. In 2007 Keller created 15 original orchestra charts for clarinetist Dave Bennett’s symphonic Pops show A Salute to Benny Goodman. This show, composed for jazz band and full symphony orchestra has been performed by over 25 major US orchestras. Keller also wrote Bennett's second orchestra Pops show Clarinet Is King, featuring 10 new original Keller arrangements of songs from Artie Shaw, Pete Fountain, and Jimmy Dorsey. -

The Jazz Record

oCtober 2019—ISSUe 210 YO Ur Free GUide TO tHe NYC JaZZ sCene nyCJaZZreCord.Com BLAKEYART INDESTRUCTIBLE LEGACY david andrew akira DR. billy torn lamb sakata taylor on tHe Cover ART BLAKEY A INDESTRUCTIBLE LEGACY L A N N by russ musto A H I G I A N The final set of this year’s Charlie Parker Jazz Festival and rhythmic vitality of bebop, took on a gospel-tinged and former band pianist Walter Davis, Jr. With the was by Carl Allen’s Art Blakey Centennial Project, playing melodicism buoyed by polyrhythmic drumming, giving replacement of Hardman by Russian trumpeter Valery songs from the Jazz Messengers songbook. Allen recalls, the music a more accessible sound that was dubbed Ponomarev and the addition of alto saxophonist Bobby “It was an honor to present the project at the festival. For hardbop, a name that would be used to describe the Watson to the band, Blakey once again had a stable me it was very fitting because Charlie Parker changed the Jazz Messengers style throughout its long existence. unit, replenishing his spirit, as can be heard on the direction of jazz as we know it and Art Blakey changed By 1955, following a slew of trio recordings as a album Gypsy Folk Tales. The drummer was soon touring my conceptual approach to playing music and leading a sideman with the day’s most inventive players, Blakey regularly again, feeling his oats, as reflected in the titles band. They were both trailblazers…Art represented in had taken over leadership of the band with Dorham, of his next records, In My Prime and Album of the Year. -

From King Records Month 2018

King Records Month 2018 = Unedited Tweets from Zero to 180 Aug. 3, 2018 Zero to 180 is honored to be part of this year's celebration of 75 Years of King Records in Cincinnati and will once again be tweeting fun facts and little known stories about King Records throughout King Records Month in September. Zero to 180 would like to kick off things early with a tribute to King session drummer Philip Paul (who you've heard on Freddy King's "Hideaway") that is PACKED with streaming audio links, images of 45s & LPs from around the world, auction prices, Billboard chart listings and tons of cool history culled from all the important music historians who have written about King Records: “Philip Paul: The Pulse of King” https://www.zeroto180.org/?p=32149 Aug. 22, 2018 King Records Month is just around the corner - get ready! Zero to 180 will be posting a new King history piece every 3 days during September as well as October. There will also be tweeting lots of cool King trivia on behalf of Xavier University's 'King Studios' historic preservation collaborative - a music history explosion that continues with this baseball-themed celebration of a novelty hit that dominated the year 1951: LINK to “Chew Tobacco Rag” Done R&B (by Lucky Millinder Orchestra) https://www.zeroto180.org/?p=27158 Aug. 24, 2018 King Records helped pioneer the practice of producing R&B versions of country hits and vice versa - "Chew Tobacco Rag" (1951) and "Why Don't You Haul Off and Love Me" (1949) being two examples of such 'crossover' marketing.