Eradicating Smallpox

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smallpox ( Variola )

Division of Disease Control What Do I Need to Know? Smallpox ( Variola ) What is Smallpox? Smallpox is a serious contagious disease that can be fatal. It is caused by the variola virus, a member of the Poxviridae family. The World Health Organization declared smallpox eliminated from the world in 1980. Who is at risk for Smallpox? Because smallpox has been eliminated, no one will be exposed to a naturally occurring case of smallpox. Smallpox is considered one of the viruses that maybe used in an attack by bioterrorists. Anyone who has not received smallpox vaccine is at risk if exposed to the virus. Also, people who received the vaccine may be at risk if exposed to smallpox because the protection declines five to ten years after one dose and possibly longer after two or more doses. The United States stopped routine childhood vaccination against smallpox in 1972. The last case of smallpox in the United States was in 1949 and the last naturally occurring case occurred in 1977 in Somalia. What are the symptoms of Smallpox? The first stage of the illness lasts two to five days with symptoms that include a high fever of 102˚F – 104˚F, a general feeling of discomfort, severe headache, backache, abdominal pain, and weakness. Most people will be severely ill and bedridden during this stage. By the third or fourth day of this stage, the fever usually drops. Following this stage, soars appear in the mouth and throat, but they may not be noticed by the infected person. The rash begins less than 24 hours after the sores in the mouth and throat appear. -

Vaccinia Belongs to a Family of Viruses That Is Closely Related to the Smallpox Virus

VACCINIA INFECTION What is it? Vaccinia belongs to a family of viruses that is closely related to the smallpox virus. Because of the similarities between the smallpox and vaccinia viruses, the vaccinia virus is used in the smallpox vaccine. When this virus is used as a vaccine, it allows our immune systems to develop immunity against smallpox. The smallpox vaccine does not actually contain smallpox virus and cannot cause smallpox. Vaccination usually prevents smallpox infection for at least ten years. The vaccinia vaccine against smallpox was used to successfully eradicate smallpox from the human population. More recently, this virus has also become of interest due to concerns about smallpox being used as an agent of bioterrorism. How is the virus spread? Vaccinia can be spread by touching the vaccination site before it has fully healed or by touching clothing or bandages that have been contaminated with the live virus during vaccination. In this manner, vaccinia can spread to other parts of the body and to other individuals. It cannot be spread through the air. What are the symptoms of vaccinia? Vaccinia virus symptoms are similar to smallpox, but milder. Vaccinia may cause rash, fever, headache and body aches. In certain individuals, such as those with weak immune systems, the symptoms can be more severe. What are the potential side effects of the vaccinia vaccine for smallpox? Normal reactions are mild and go away without any treatment.These include: Soreness and redness in the arm where the vaccine was given Slightly swollen, sore glands in the armpits Low grade fever One in approximately three people will feel badly enough to miss school, work or recreational activities Trouble sleeping Serious reactions are not very common but can occur in about 1,000 in every 1 million people who are vaccinated for the first time. -

Adult Vaccines

What do flu, whooping cough, measles, shingles and pneumonia have in common? 1 They’re viruses that can make you very sick. 2 Vaccines can help prevent them. Protect yourself and those you care about. Get vaccinated at a network pharmacy near you. • Ask your pharmacist which vaccines are right for you. • Find out if your pharmacist can administer the recommended vaccinations. • Many vaccinations are covered by your plan at participating retail pharmacies. • Don’t forget to present your member ID card to the pharmacist at the time of service! The following vaccines are available and can be administered by pharmacists at participating network pharmacies: • Flu (seasonal influenza) • Meningitis • Travel Vaccines (typhoid, yellow • Tetanus/Diphtheria/Pertussis • Pneumonia fever, etc.) • Hepatitis • Rabies • Childhood Vaccines (MMR, etc.) • Human Papillomavirus (HPV) • Shingles/Zoster See other side for recommended adult vaccinations. The vaccinations you need ALL adults should get vaccinated for1: • Flu, every year. It’s especially important for pregnant women, older adults and people with chronic health conditions. • Tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis (whooping cough). Adults should get a one-time dose of the Tdap vaccine. It’s different from the tetanus vaccine (Td), which is given every 10 years. You may need additional vaccinations depending on your age1: Young adults not yet vaccinated need: Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine series (3 doses) if you are: • Female age 26 or younger • Male age 21 or younger • Male age 26 or younger who has sex with men, who is immunocompromised or who has HIV Adults born in the U.S. in 1957 or after need: Measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine2 Adults should get at least one dose of MMR vaccine, unless they’ve already gotten this vaccine or have immunity to measles, mumps and rubella Adults born in the U.S. -

Bridge Index

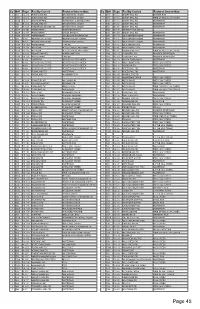

Co Br# Page Facility Carried Featured Intersedtion Co Br# Page Facility Carried Featured Intersedtion 1 001 12 2-G RISING SUN RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 087 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD BURRIS RUN 1 001A 12 2-G RISING SUN RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 088 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD TRIB OF RED CLAY CREEK 1 001B 12 2-F KENNETT PIKE WATERWAY & ABANDON RR 1 089 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD. WATERWAY 1 002 9 12-G ROCKLAND RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 090 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD. WATERWAY 1 003 9 11-G THOMPSON BRIDGE RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 091 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD. WATERWAY 1 004P 13 3-B PEDESTRIAN NORTHEAST BLVD 1 092 9 11-E KENNET PIKE (DE 52) 1 006P 12 4-G PEDESTRIAN UNION STREET 1 093 9 10-D SNUFF MILL RD WATERWAY 1 007P 11 8-H PEDESTRIAN OGLETOWN STANTON RD 1 096 9 11-D OLD KENNETT ROAD WATERWAY 1 008 9 9-G BEAVER VALLEY RD. BEAVER VALLEY CREEK 1 097 9 11-C OLD KENNETT ROAD WATERWAY 1 009 9 9-G SMITHS BRIDGE RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 098 9 11-C OLD KENNETT ROAD WATERWAY 1 010P 10 12-F PEDESTRIAN I 495 NB 1 099 9 11-C OLD KENNETT RD WATERWAY 1 011N 12 1-H SR 141NB RD 232, ROCKLAND ROAD 1 100 9 10-C OLD KENNETT RD. WATERWAY 1 011S 12 1-H SR 141SB RD 232, ROCKLAND ROAD 1 105 9 12-C GRAVES MILL RD TRIB OF RED CLAY CREEK 1 012 9 10-H WOODLAWN RD. -

Malaria History

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License. Your use of this material constitutes acceptance of that license and the conditions of use of materials on this site. Copyright 2006, The Johns Hopkins University and David Sullivan. All rights reserved. Use of these materials permitted only in accordance with license rights granted. Materials provided “AS IS”; no representations or warranties provided. User assumes all responsibility for use, and all liability related thereto, and must independently review all materials for accuracy and efficacy. May contain materials owned by others. User is responsible for obtaining permissions for use from third parties as needed. Malariology Overview History, Lifecycle, Epidemiology, Pathology, and Control David Sullivan, MD Malaria History • 2700 BCE: The Nei Ching (Chinese Canon of Medicine) discussed malaria symptoms and the relationship between fevers and enlarged spleens. • 1550 BCE: The Ebers Papyrus mentions fevers, rigors, splenomegaly, and oil from Balantines tree as mosquito repellent. • 6th century BCE: Cuneiform tablets mention deadly malaria-like fevers affecting Mesopotamia. • Hippocrates from studies in Egypt was first to make connection between nearness of stagnant bodies of water and occurrence of fevers in local population. • Romans also associated marshes with fever and pioneered efforts to drain swamps. • Italian: “aria cattiva” = bad air; “mal aria” = bad air. • French: “paludisme” = rooted in swamp. Cure Before Etiology: Mid 17th Century - Three Theories • PC Garnham relates that following: An earthquake caused destruction in Loxa in which many cinchona trees collapsed and fell into small lake or pond and water became very bitter as to be almost undrinkable. Yet an Indian so thirsty with a violent fever quenched his thirst with this cinchona bark contaminated water and was better in a day or two. -

Smallpox Overview

SMALLPOX FACT SHEET Smallpox Overview The Disease Smallpox is a serious, contagious, and sometimes fatal infectious disease. There is no specific treatment for smallpox disease, and the only prevention is vaccination. The name smallpox is derived from the Latin word for “spotted” and refers to the raised bumps that appear on the face and body of an infected person. There are two clinical forms of smallpox. Variola major is the severe and most common form of smallpox, with a more extensive rash and higher fever. There are four types of variola major smallpox: ordinary (the most frequent type, accounting for 90% or more of cases); modified (mild and occurring in previously vaccinated persons); flat; and hemorrhagic (both rare and very severe). Historically, variola major has an overall fatality rate of about 30%; however, flat and hemorrhagic smallpox usually are fatal. Variola minor is a less common presentation of smallpox, and a much less severe disease, with death rates historically of 1% or less. Smallpox outbreaks have occurred from time to time for thousands of years, but the disease is now eradicated after a successful worldwide vaccination program. The last case of smallpox in the United States was in 1949. The last naturally occurring case in the world was in Somalia in 1977. After the disease was eliminated from the world, routine vaccination against smallpox among the general public was stopped because it was no longer necessary for prevention. Where Smallpox Comes From Smallpox is caused by the variola virus that emerged in human populations thousands of years ago. Except for laboratory stockpiles, the variola virus has been eliminated. -

A Guide to Vaccinations for Parents

A GUIDE TO VACCINATIONS FOR PARENTS What are vaccines? When should my child be vaccinated? Why does my child need the HPV vaccine? HISTORY OF VACCINATIONS Smallpox is a serious infectious disease that causes fever and a distinctive, progressive 600 1796 skin rash. years ago Edward Jenner developed Variolation, intentionally a vaccine against smallpox. Cases of paralysis from polio in the U.S. exposing an individual to Almost 200 years later, in 1980, in the early 1950s: smallpox material, traces back the World Health Organization more than to 16th-century China. This declared that smallpox process resulted in a milder had been eradicated, 15,000 form of the disease. or wiped out. In the year 2017: Childhood vaccines can prevent 14 potentially serious 0 diseases or conditions throughout your child’s lifetime. 1955 1940s 1885 Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine The routine immunization Louis Pasteur developed a was proven safe and effective. schedule included vaccines vaccine against rabies. The Polio has now been eliminated against four potentially serious rabies vaccine series, which in the U.S., and organizations diseases (smallpox, diphtheria, can be given to people who are currently working tetanus, and pertussis). may have been exposed to to eradicate polio Now the schedule includes the virus, has made rabies worldwide. vaccines to prevent a total infection very rare in the of 14 conditions. United States. In the U.S., vaccines go through three phases of clinical trials to make sure they are safe and effective before they are licensed. 2006 Today The HPV vaccine was Vaccine research licensed in the U.S. -

Malaria: Bad for Business Why Investing in Ending Malaria Provides Some of the Highest Economic Returns

Malaria: Bad for business Why investing in ending malaria provides some of the highest economic returns. Malaria’s burden on the health and wealth of nations While huge progress has been made in recent years, one of the most striking signs of the global impact of the 215 million cases of malaria reported last year is that up to 40% of public health spending goes on the disease in the most heavily affected countries. But malaria reaches far beyond public health, taking its toll on households, local and multinational business profits, and national economic development. Critically, annual economic growth in countries with high malaria transmission has historically been lower than in countries without malaria. In some African countries, malaria reduces GDP growth up to an estimated 1.3%. Malaria costs productivity. Adults are forced to be absent from work, children miss school, and households spend disproportionately on health when they can least afford it. But it need not be this way. With developing countries, donors and private sector firms beginning to take real action, we can be the generation that ends malaria for good and boosts prosperity for all. The economic growth penalty Malaria’s impact on national economies Malaria and poverty occupy common ground. Where the burden of malaria is highest, economic prosperity is lowest. We know that poverty can promote malaria transmission, and that malaria causes poverty by blocking economic growth. Research shows that malaria can strain national economics, having a deleterious impact on some nations’ GDP by as much as an estimated 5 - 6%. It keeps households in poverty, discourages domestic and foreign investment and tourism, affects land use patterns, and reduces productivity through lost work days and diminished job performance. -

Viability of B. Typhosus in Stored Shell Oysters

PUBLIC HEALTH REPORTS VOL. 40 APRIL 24, 1925 No. 17 VIABILITY OF B. TYPHOSUS IN STORED SHELL OYSTERS By CONRAD KINYOuN, Assistant Bacteriologist, hlygienic Laboratory, United Stztes Ptiblic Ilealti Serviee The object of this work was to determine whether oysters con- taminated with B. typhosuis and then stored unider uisual market conditions woul(l remain potentially infectious over a length of time sufficient to allow them to reach the consumer. Conflicting opinions are now current as to the length of time the causative agent of typhoid fever can remain viable in the oyster, and even as to whether the oyster can harbor the organisms at all. Obviouisly an oyster which harbors typhoidl organismns for as short a time as 24 hours becomes a potential infecting, agent for thlat time. Practi- cally it is of interest to know whether the time elapsing between the remov-al of the oyster from the bed and( actual consumption after passing through customary commercial channels is sufficient for oysters to rid themselves of possible infection. As early as 1603, oysters were incriminate(d in intestinal disor(lers, when suspicion was directed toward them by an illness of Henry IV of France (7). It was not uIntil the close of the nineteenth century, however, that oysters and shellfislh as agents of (lisease transmission receive(d particular attention. In October, 1894, Conn focused attention on the oyster by his investigation of the now famous Wesleyan outbreak, an(d thoughl only thlree outbreaks of typhoid fever were definitely traced to the oyster before 19,25, these stimulated wide interest and consequent study, with atten(lant epidemiological and bacteriological investigations. -

Measles: Chapter 7.1 Chapter 7: Measles Paul A

VPD Surveillance Manual 7 Measles: Chapter 7.1 Chapter 7: Measles Paul A. Gastanaduy, MD, MPH; Susan B. Redd; Nakia S. Clemmons, MPH; Adria D. Lee, MSPH; Carole J. Hickman, PhD; Paul A. Rota, PhD; Manisha Patel, MD, MS I. Disease Description Measles is an acute viral illness caused by a virus in the family paramyxovirus, genus Morbillivirus. Measles is characterized by a prodrome of fever (as high as 105°F) and malaise, cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis, followed by a maculopapular rash.1 The rash spreads from head to trunk to lower extremities. Measles is usually a mild or moderately severe illness. However, measles can result in complications such as pneumonia, encephalitis, and death. Approximately one case of encephalitis2 and two to three deaths may occur for every 1,000 reported measles cases.3 One rare long-term sequelae of measles virus infection is subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), a fatal disease of the central nervous system that generally develops 7–10 years after infection. Among persons who contracted measles during the resurgence in the United States (U.S.) in 1989–1991, the risk of SSPE was estimated to be 7–11 cases/100,000 cases of measles.4 The risk of developing SSPE may be higher when measles occurs prior to the second year of life.4 The average incubation period for measles is 11–12 days,5 and the average interval between exposure and rash onset is 14 days, with a range of 7–21 days.1, 6 Persons with measles are usually considered infectious from four days before until four days after onset of rash with the rash onset being considered as day zero. -

Measles Diagnostic Tool

Measles Prodrome and Clinical evolution E Fever (mild to moderate) E Cough E Coryza E Conjunctivitis E Fever spikes as high as 105ºF Koplik’s spots Koplik’s Spots E E Viral enanthem of measles Rash E Erythematous, maculopapular rash which begins on typically starting 1-2 days before the face (often at hairline and behind ears) then spreads to neck/ the rash. Appearance is similar to “grains of salt on a wet background” upper trunk and then to lower trunk and extremities. Evolution and may become less visible as the of rash 1-3 days. Palms and soles rarely involved. maculopapular rash develops. Rash INCUBATION PERIOD Fever, STARTS on face (hairline & cough/coryza/conjunctivitis behind ears), spreads to trunk, Average 8-12 days from exposure to onset (sensitivity to light) and then to thighs/ feet of prodrome symptoms 0 (average interval between exposure to onset rash 14 day [range 7-21 days]) -4 -3 -2 -1 1234 NOT INFECTIOUS higher fever (103°-104°) during this period rash fades in same sequence it appears INFECTIOUS 4 days before rash and 4 days after rash Not Measles Rubella Varicella cervical lymphadenopathy. Highly variable but (Aka German Measles) (Aka Chickenpox) Rash E often maculopapular with Clinical manifestations E Clinical manifestations E Generally mild illness with low- Mild prodrome of fever and malaise multiforme-like lesions and grade fever, malaise, and lymph- may occur one to two days before may resemble scarlet fever. adenopathy (commonly post- rash. Possible low-grade fever. Rash often associated with painful edema hands and feet. auricular and sub-occipital). -

Kaposi Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Uals Were 2 to 16 Times More Likely to Develop Kaposi Sarcoma Than Were Uninfected Individuals

Report on Carcinogens, Fourteenth Edition For Table of Contents, see home page: http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/go/roc Kaposi Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus uals were 2 to 16 times more likely to develop Kaposi sarcoma than were uninfected individuals. In some studies, the risk of Kaposi sar- CAS No.: none assigned coma increased with increasing viral load of KSHV (Sitas et al. 1999, Known to be a human carcinogen Newton et al. 2003a,b, 2006, Albrecht et al. 2004). Most KSHV-infected patients who develop Kaposi sarcoma have Also known as KSHV or human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) immune systems compromised either by HIV-1 infection or as a re- Carcinogenicity sult of drug treatments after organ or tissue transplants. The timing of infection with HIV-1 may also play a role in development of Ka- Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is known to be a posi sarcoma. Acquiring HIV-1 infection prior to KSHV infection human carcinogen based on sufficient evidence from studies in hu- may increase the risk of epidemic Kaposi sarcoma by 50% to 100%, mans. This conclusion is based on evidence from epidemiological compared with acquiring HIV-1 infection at the same time as or after and molecular studies, which show that KSHV causes Kaposi sar- KSHV infection. Nevertheless, patients with the classic or endemic coma, primary effusion lymphoma, and a plasmablastic variant of forms of Kaposi sarcoma are not suspected of having suppressed im- multicentric Castleman disease, and on supporting mechanistic data. mune systems, suggesting that immunosuppression is not required KSHV causes cancer, primarily but not exclusively in people with for development of Kaposi sarcoma.