Measles: Chapter 7.1 Chapter 7: Measles Paul A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(ACIP) General Best Guidance for Immunization

9. Special Situations Updates Major revisions to this section of the best practices guidance include the timing of intramuscular administration and the timing of clotting factor deficiency replacement. Concurrent Administration of Antimicrobial Agents and Vaccines With a few exceptions, use of an antimicrobial agent does not interfere with the effectiveness of vaccination. Antibacterial agents have no effect on inactivated, recombinant subunit, or polysaccharide vaccines or toxoids. They also have no effect on response to live, attenuated vaccines, except BCG vaccines. Antimicrobial or immunosuppressive agents may interfere with the immune response to BCG and should only be used under medical supervision (for additional information, see www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/b/bcg/bcg_pi.pdf). Antiviral drugs used for treatment or prophylaxis of influenza virus infections have no effect on the response to inactivated influenza vaccine (2). However, live, attenuated influenza vaccine should not be administered until 48 hours after cessation of therapy with antiviral influenza drugs. If feasible, to avoid possible reduction in vaccine effectiveness, antiviral medication should not be administered for 14 days after LAIV administration (2). If influenza antiviral medications are administered within 2 weeks after receipt of LAIV, the LAIV dose should be repeated 48 or more hours after the last dose of zanamavir or oseltamivir. The LAIV dose should be repeated 5 days after peramivir and 17 days after baloxavir. Alternatively, persons receiving antiviral drugs within the period 2 days before to 14 days after vaccination with LAIV may be revaccinated with another approved vaccine formulation (e.g., IIV or recombinant influenza vaccine). Antiviral drugs active against herpesviruses (e.g., acyclovir or valacyclovir) might reduce the efficacy of vaccines containing live, attenuated varicella zoster virus (i.e., Varivax and ProQuad) (3,4). -

Frequently Asked Questions About Measles Immunizations

Immunization Unit Assessment, Compliance, and Evaluation Group Measles FAQs Q: When did the vaccine for measles become available? A: The first measles vaccines were available in 1963, and were replaced with a much better vaccine in 1968. Q: Do people who received MMR in the 1960s need to have their dose repeated? A: Not necessarily. People who have documentation of receiving a live measles vaccine in the 1960s do not need to be revaccinated. People who were vaccinated with a killed or inactivated measles vaccine, or vaccine of unknown type, should be revaccinated with at least 1 dose of MMR. Q: What kind of vaccine is it? A: The vaccines available in the United States that protect against measles are the MMR and MMRV, which protects against measles, mumps, and rubella or measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella (chickenpox). They are both live attenuated, or weakened, vaccines. Q: Which vaccine can I get, the MMR or the MMRV? A: The MMRV is only approved for people aged 12 months – 12 years. The MMR is approved for anyone 6 months of age and older, but it is routinely recommended for use in people 12 months of age and older. Any dose of MMR received before 12 months of age is not considered valid and should be repeated in 4 weeks or at age 12 months, whichever is later. Q: How is the vaccine given? A: The vaccine is administered in the fatty layer of tissue underneath the skin. Q: Is the measles shot just a one-time dose? A: The measles vaccine is very effective. -

Adult Vaccines

What do flu, whooping cough, measles, shingles and pneumonia have in common? 1 They’re viruses that can make you very sick. 2 Vaccines can help prevent them. Protect yourself and those you care about. Get vaccinated at a network pharmacy near you. • Ask your pharmacist which vaccines are right for you. • Find out if your pharmacist can administer the recommended vaccinations. • Many vaccinations are covered by your plan at participating retail pharmacies. • Don’t forget to present your member ID card to the pharmacist at the time of service! The following vaccines are available and can be administered by pharmacists at participating network pharmacies: • Flu (seasonal influenza) • Meningitis • Travel Vaccines (typhoid, yellow • Tetanus/Diphtheria/Pertussis • Pneumonia fever, etc.) • Hepatitis • Rabies • Childhood Vaccines (MMR, etc.) • Human Papillomavirus (HPV) • Shingles/Zoster See other side for recommended adult vaccinations. The vaccinations you need ALL adults should get vaccinated for1: • Flu, every year. It’s especially important for pregnant women, older adults and people with chronic health conditions. • Tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis (whooping cough). Adults should get a one-time dose of the Tdap vaccine. It’s different from the tetanus vaccine (Td), which is given every 10 years. You may need additional vaccinations depending on your age1: Young adults not yet vaccinated need: Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine series (3 doses) if you are: • Female age 26 or younger • Male age 21 or younger • Male age 26 or younger who has sex with men, who is immunocompromised or who has HIV Adults born in the U.S. in 1957 or after need: Measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine2 Adults should get at least one dose of MMR vaccine, unless they’ve already gotten this vaccine or have immunity to measles, mumps and rubella Adults born in the U.S. -

Emerging Global Epidemiology of Measles and Public Health Response to Confirmed Case in Rhode Island

PUBLIC HEALTH Emerging Global Epidemiology of Measles and Public Health Response to Confirmed Case in Rhode Island ANANDA SANKAR BANDYOPADHYAY, MBBS, MPH; UTPALA BANDY, MD ABSTRACT Organization (WHO) geographical Region of the Americas Measles is a highly contagious viral disease and rapid achieved measles elimination by interrupting transmission identification and control of cases/outbreaks are import- of the endemic strain of measles virus.3 However, importa- ant global health priorities. Measles was declared elimi- tions from endemic countries continued throughout the last nated from the United States in March 2000. However, decade and a median of 56 cases of measles were reported in importations from endemic countries continued through the United States during the 2001-2008 period.4 A major re- out the last decade and in 2011, the United States report- surgence of measles occurred in the WHO European Region ed its highest number of cases in 15 years. With a global in 2011, with more than 13,000 laboratory-confirmed cases, snapshot of current measles epidemiology and the per- nearly three times higher than the total number of laborato- sistent risk of transnational spread based on population ry-confirmed cases reported in 2010.5 Ninety percent of the movement as the backdrop, this article describes the measles cases reported from the WHO European Region in rare event of a measles case identification in the state 2011 had not been vaccinated or had no documentation of of Rhode Island and the corresponding public health prior vaccination.6 Two-hundred and sixteen laboratory-con- response. As the global effort for measles elimination firmed cases were reported in the United States in 2011, the continues to make significant progress, sensitive public highest number of cases since 1996.7 Rhode Island reported health surveillance systems and strong routine immuni- its first case of measles since 1996 in April 2011. -

Period of Presymptomatic Transmission

PERIOD OF PRESYMPTOMATIC TRANSMISSION RAG 17/09/2020 QUESTION Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 before onset of symptoms in the index is known, and this is supported by data on viral shedding. Based on the assumption that the viral load in the upper respiratory tract is highest one day before and the days immediately after onset of symptoms, current procedures for contact tracing (high and low risk contacts), go back two days before start of symptoms in the index (or sampling date in asymptomatic persons) (1), (2), (3). This is in line with the ECDC and WHO guidelines to consider all potential contacts of a case starting 48h before symptom onset (4) (5). The question was asked whether this period should be extended. BACKGROUND Viral load According to ECDC and WHO, viral RNA can be detected from one to three days before the onset of symptoms (6,7). The highest viral loads, as measured by RT-PCR, are observed around the day of symptom onset, followed by a gradual decline over time (1,3,8–10) . Period of transmission A much-cited study by He and colleagues and published in Nature used publicly available data from 77 transmission pairs to model infectiousness, using the reported serial interval (the period between symptom onset in infector-infectee) and combining this with the median incubation period. They conclude that infectiousness peaks around symptom onset. The initial article stated that the infectious period started at 2.3 days before symptom onset. However, a Swiss team spotted an error in their code and the authors issued a correction, stating the infectious period can start from as early as 12.3 days before symptom onset (11). -

Viability of B. Typhosus in Stored Shell Oysters

PUBLIC HEALTH REPORTS VOL. 40 APRIL 24, 1925 No. 17 VIABILITY OF B. TYPHOSUS IN STORED SHELL OYSTERS By CONRAD KINYOuN, Assistant Bacteriologist, hlygienic Laboratory, United Stztes Ptiblic Ilealti Serviee The object of this work was to determine whether oysters con- taminated with B. typhosuis and then stored unider uisual market conditions woul(l remain potentially infectious over a length of time sufficient to allow them to reach the consumer. Conflicting opinions are now current as to the length of time the causative agent of typhoid fever can remain viable in the oyster, and even as to whether the oyster can harbor the organisms at all. Obviouisly an oyster which harbors typhoidl organismns for as short a time as 24 hours becomes a potential infecting, agent for thlat time. Practi- cally it is of interest to know whether the time elapsing between the remov-al of the oyster from the bed and( actual consumption after passing through customary commercial channels is sufficient for oysters to rid themselves of possible infection. As early as 1603, oysters were incriminate(d in intestinal disor(lers, when suspicion was directed toward them by an illness of Henry IV of France (7). It was not uIntil the close of the nineteenth century, however, that oysters and shellfislh as agents of (lisease transmission receive(d particular attention. In October, 1894, Conn focused attention on the oyster by his investigation of the now famous Wesleyan outbreak, an(d thoughl only thlree outbreaks of typhoid fever were definitely traced to the oyster before 19,25, these stimulated wide interest and consequent study, with atten(lant epidemiological and bacteriological investigations. -

Measles Diagnostic Tool

Measles Prodrome and Clinical evolution E Fever (mild to moderate) E Cough E Coryza E Conjunctivitis E Fever spikes as high as 105ºF Koplik’s spots Koplik’s Spots E E Viral enanthem of measles Rash E Erythematous, maculopapular rash which begins on typically starting 1-2 days before the face (often at hairline and behind ears) then spreads to neck/ the rash. Appearance is similar to “grains of salt on a wet background” upper trunk and then to lower trunk and extremities. Evolution and may become less visible as the of rash 1-3 days. Palms and soles rarely involved. maculopapular rash develops. Rash INCUBATION PERIOD Fever, STARTS on face (hairline & cough/coryza/conjunctivitis behind ears), spreads to trunk, Average 8-12 days from exposure to onset (sensitivity to light) and then to thighs/ feet of prodrome symptoms 0 (average interval between exposure to onset rash 14 day [range 7-21 days]) -4 -3 -2 -1 1234 NOT INFECTIOUS higher fever (103°-104°) during this period rash fades in same sequence it appears INFECTIOUS 4 days before rash and 4 days after rash Not Measles Rubella Varicella cervical lymphadenopathy. Highly variable but (Aka German Measles) (Aka Chickenpox) Rash E often maculopapular with Clinical manifestations E Clinical manifestations E Generally mild illness with low- Mild prodrome of fever and malaise multiforme-like lesions and grade fever, malaise, and lymph- may occur one to two days before may resemble scarlet fever. adenopathy (commonly post- rash. Possible low-grade fever. Rash often associated with painful edema hands and feet. auricular and sub-occipital). -

Vaccine Information for PARENTS and CAREGIVERS

NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR COMMUNICABLE DISEASES Division of the National Health Laboratory Service VACCINE INFOR MATION FOR PARENTS & CAREGIVERS First Edition November 2016 Editors-in-Chief Nkengafac Villyen Motaze (MD, MSc, PhD fellow), Melinda Suchard (MBBCh, FCPath (SA), MMed) Edited by: Cheryl Cohen, (MBBCh, FCPath (SA) Micro, DTM&H, MSc (Epi), Phd) Lee Baker, (Dip Pharm) Lucille Blumberg, (MBBCh, MMed (Micro) ID (SA) FFTM (RCPS, Glasgow) DTM&H DOH DCH) Published by: Ideas Wise and Wonderful (IWW) for National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) First Edition: Copyright © 2016 Contributions by: Clement Adu-Gyamfi (BSc Hons, MSc), Jayendrie Thaver (BSc), Kerrigan McCarthy, (MBBCh, FCPath (SA), DTM&H, MPhil (Theol) Kirsten Redman (BSc Hons), Nishi Prabdial-Sing (PhD), Nonhlanhla Mbenenge (MBBCh, MMED) Philippa Hime (midwife), Vania Duxbury (BSc Hons), Wayne Howard (BSc Hons) Acknowledgments: Amayeza, Vaccine Information Centre (http://www.amayeza-info.co.za/) Centre for Communicable Diseases Fact Sheets (http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/) World Health Organization Fact Sheets (http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/en/) National Department of Health, South Africa (http://www.health.gov.za/) Disclaimer This book is intended as an educational tool only. Information may be subject to change as schedules or formulations are updated. Summarized and simplified information is presented in this booklet. For full prescribing information and contraindications for vaccinations, please consult individual package inserts. There has been -

Kaposi Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Uals Were 2 to 16 Times More Likely to Develop Kaposi Sarcoma Than Were Uninfected Individuals

Report on Carcinogens, Fourteenth Edition For Table of Contents, see home page: http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/go/roc Kaposi Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus uals were 2 to 16 times more likely to develop Kaposi sarcoma than were uninfected individuals. In some studies, the risk of Kaposi sar- CAS No.: none assigned coma increased with increasing viral load of KSHV (Sitas et al. 1999, Known to be a human carcinogen Newton et al. 2003a,b, 2006, Albrecht et al. 2004). Most KSHV-infected patients who develop Kaposi sarcoma have Also known as KSHV or human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) immune systems compromised either by HIV-1 infection or as a re- Carcinogenicity sult of drug treatments after organ or tissue transplants. The timing of infection with HIV-1 may also play a role in development of Ka- Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is known to be a posi sarcoma. Acquiring HIV-1 infection prior to KSHV infection human carcinogen based on sufficient evidence from studies in hu- may increase the risk of epidemic Kaposi sarcoma by 50% to 100%, mans. This conclusion is based on evidence from epidemiological compared with acquiring HIV-1 infection at the same time as or after and molecular studies, which show that KSHV causes Kaposi sar- KSHV infection. Nevertheless, patients with the classic or endemic coma, primary effusion lymphoma, and a plasmablastic variant of forms of Kaposi sarcoma are not suspected of having suppressed im- multicentric Castleman disease, and on supporting mechanistic data. mune systems, suggesting that immunosuppression is not required KSHV causes cancer, primarily but not exclusively in people with for development of Kaposi sarcoma. -

Superspreading of Airborne Pathogens in a Heterogeneous World Julius B

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Superspreading of airborne pathogens in a heterogeneous world Julius B. Kirkegaard*, Joachim Mathiesen & Kim Sneppen Epidemics are regularly associated with reports of superspreading: single individuals infecting many others. How do we determine if such events are due to people inherently being biological superspreaders or simply due to random chance? We present an analytically solvable model for airborne diseases which reveal the spreading statistics of epidemics in socio-spatial heterogeneous spaces and provide a baseline to which data may be compared. In contrast to classical SIR models, we explicitly model social events where airborne pathogen transmission allows a single individual to infect many simultaneously, a key feature that generates distinctive output statistics. We fnd that diseases that have a short duration of high infectiousness can give extreme statistics such as 20% infecting more than 80%, depending on the socio-spatial heterogeneity. Quantifying this by a distribution over sizes of social gatherings, tracking data of social proximity for university students suggest that this can be a approximated by a power law. Finally, we study mitigation eforts applied to our model. We fnd that the efect of banning large gatherings works equally well for diseases with any duration of infectiousness, but depends strongly on socio-spatial heterogeneity. Te statistics of an on-going epidemic depend on a number of factors. Most directly: How easily is it transmit- ted? And how long are individuals afected and infectious? Scientifc papers and news paper articles alike tend to summarize the intensity of epidemics in a single number, R0 . Tis basic reproduction number is a measure of the average number of individuals an infected patient will successfully transmit the disease to. -

AAMC Standardized Immunization Form

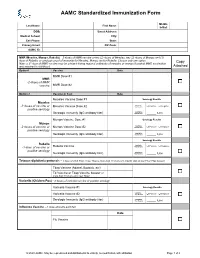

AAMC Standardized Immunization Form Middle Last Name: First Name: Initial: DOB: Street Address: Medical School: City: Cell Phone: State: Primary Email: ZIP Code: AAMC ID: MMR (Measles, Mumps, Rubella) – 2 doses of MMR vaccine or two (2) doses of Measles, two (2) doses of Mumps and (1) dose of Rubella; or serologic proof of immunity for Measles, Mumps and/or Rubella. Choose only one option. Copy Note: a 3rd dose of MMR vaccine may be advised during regional outbreaks of measles or mumps if original MMR vaccination was received in childhood. Attached Option1 Vaccine Date MMR Dose #1 MMR -2 doses of MMR vaccine MMR Dose #2 Option 2 Vaccine or Test Date Measles Vaccine Dose #1 Serology Results Measles Qualitative -2 doses of vaccine or Measles Vaccine Dose #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Mumps Vaccine Dose #1 Serology Results Mumps Qualitative -2 doses of vaccine or Mumps Vaccine Dose #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Serology Results Rubella Qualitative Positive Negative -1 dose of vaccine or Rubella Vaccine Titer Results: positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis – 1 dose of adult Tdap; if last Tdap is more than 10 years old, provide date of last Td or Tdap booster Tdap Vaccine (Adacel, Boostrix, etc) Td Vaccine or Tdap Vaccine booster (if more than 10 years since last Tdap) Varicella (Chicken Pox) - 2 doses of varicella vaccine or positive serology Varicella Vaccine #1 Serology Results Qualitative Varicella Vaccine #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Quantitative Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Influenza Vaccine --1 dose annually each fall Date Flu Vaccine © 2020 AAMC. -

Using Proper Mean Generation Intervals in Modeling of COVID-19

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 05 July 2021 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.691262 Using Proper Mean Generation Intervals in Modeling of COVID-19 Xiujuan Tang 1, Salihu S. Musa 2,3, Shi Zhao 4,5, Shujiang Mei 1 and Daihai He 2* 1 Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Shenzhen, China, 2 Department of Applied Mathematics, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China, 3 Department of Mathematics, Kano University of Science and Technology, Wudil, Nigeria, 4 The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China, 5 Shenzhen Research Institute of Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen, China In susceptible–exposed–infectious–recovered (SEIR) epidemic models, with the exponentially distributed duration of exposed/infectious statuses, the mean generation interval (GI, time lag between infections of a primary case and its secondary case) equals the mean latent period (LP) plus the mean infectious period (IP). It was widely reported that the GI for COVID-19 is as short as 5 days. However, many works in top journals used longer LP or IP with the sum (i.e., GI), e.g., >7 days. This discrepancy will lead to overestimated basic reproductive number and exaggerated expectation of Edited by: infection attack rate (AR) and control efficacy. We argue that it is important to use Reza Lashgari, suitable epidemiological parameter values for proper estimation/prediction. Furthermore, Institute for Research in Fundamental we propose an epidemic model to assess the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 Sciences, Iran for Belgium, Israel, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).