AVAILABLE from Stanford University Libraries, Stanford ,University, Stanford, California 94305

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013-14 Arts Report (Pdf)

2013-14 Arts Explosion Rocks Stanford 1 A Private Art Collection Becomes a Stanford Collection 2-3 Curricular Innovation 4-5 Interdisciplinary Dexterity 6-7 Anatomy of an Exhibition 8 Visual Thinkers 9 Renaissance Man 10-11 Festival Jérôme Bel 12 The Next Bing Thing 13 Sound Pioneer 14 Politicians, Producers & Directors 15 Theater Innovators 16 Museums & Performance Organizations 17 Looking Ahead 17 Academic Arts Departments & Programs 18-19 “Arts Explosion Rocks Stanford.” Arts Centers, Institutes & Resources 20-21 Student Arts Groups 22-23 That was the headline of a May 2014 article in the San Francisco Chronicle – and it’s a great descrip- Fashion at Stanford 24 tion of the experience of the arts at Stanford in 2013-14. Honors in the Arts: The Inaugural Year 25 Support for Stanford Arts 26 It was a year of firsts: the first full season in Bing Concert Hall, the first year of two innovative curric- 2013-14 Arts Advisory Council 27 ular programs – ITALIC and Honors in the Arts - and the first year of the new “Creative Expression” Faculty & Staff 27 breadth requirement (see p. 4). Stanford Arts District 28 BING CONCERT HALL’S It was also – perhaps most prominently – a year of planning and breathless anticipation of the opening GUNN ATRIUM of the Anderson Collection at Stanford University, which took place to great fanfare in September 2014. In the midst of it all there were exciting multidisciplinary exhibitions at the Cantor Arts Center, amaz- ing student projects and performances throughout campus, and a host of visits by artists including Carrie Mae Weems, Tony Kushner, and Annie Leibovitz. -

Bibliographic Automation of Large Library Operations Using a Time-Sharing System: Phase I

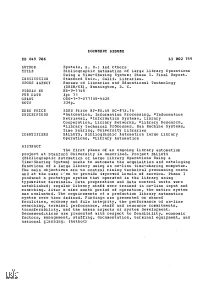

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 049 786 LI 002 759 AUTHOR Epstein, A. H.; And Cthers TITLE Bibliographic Automation of Large Library Operations Using a Time-Sharing System: Phase I. Final Report. INSTITUTION Stanford Univ., Calif. Libraries. SPONS AGENCY Bureau of Libraries and Educational Technology (DHEW/OE), Washington, D. C. BUREAU NO BR-7-1145 PUB DATE Apr 71 GRANT OEG-1-7-071145-4428 NOTE 334p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$13.16 DESCRIPTORS *Automation, Information Processing, *Information Retrieval, *Information Systems, Library Cooperation, Library Networks, *Library Research, *Library Technical Prdcesses, an Machine Systems, Time Sharing, University Libraries IDENTIFIERS BALLOTS, Bibliographic Automation Large Library Operations, *Library Automation AESTRACT The first phase of an ongoing library automation project at Stanford University is described. Project BALLOTS (Bibliographic Automation of Large Library Operations Using a Time-Sharing System) seeks to automate the acquisition and cataloging functions of a large library using an on-line time-sharing computer. The main objectives are to control rising technical processing costs and at the same t2me tc provide improved levels of service. Phase I produced a prototype system that operated in the library using typewriter terminals. Data preparation and data control units were established; regular library staff were trained in on-line input and searching. Aiter a nine month period of operation, the entire system was evaluated. The requirements of a production library automation system were then defined. Findings are presented on shared facilities, economy and file integrity, the performance of on-line searching, terminal performance, staff and resource commitments, transferability, and the human aspects of system development. -

Stanford University Architectural Collection SC1043

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt9g5041mg Online items available Guide to the Stanford University Architectural Collection SC1043 compiled by University Archives staff Department of Special Collections and University Archives October 2010 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Note This encoded finding aid is compliant with Stanford EAD Best Practice Guidelines, Version 1.0. Guide to the Stanford University SC1043 1 Architectural Collection SC1043 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Stanford University Architectural Collection creator: Stanford University Identifier/Call Number: SC1043 Physical Description: 2800 item(s) Date (inclusive): 1889-2015 Abstract: The materials consist of architectural drawings of Stanford University buildings and grounds. Conditions Governing Access The materials are open for research use; materials must be requested at least 48 hours in advance of intended use. Audio-visual materials are not available in original format, and must be reformatted to a digital use copy. Scope and Contents The materials consist of architectural drawings of Stanford University buildings and grounds. Arrangement The materials are arranged by building or drawing name. Conditions Governing Use All requests to reproduce, publish, quote from, or otherwise use collection materials must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California 94304-6064. Consent is given on behalf of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission from the copyright owner. Such permission must be obtained from the copyright owner, heir(s) or assigns. -

Stanford University School of Medicine Office of Student Affairs, November 22, 2004

PROCEDURES, POLICIES, AND ESSENTIAL INFORMATION FOR THE MD TRAINING PROGRAM 2004-2005 Compiled and published by the Stanford University School of Medicine Office of Student Affairs, November 22, 2004. While every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the information available at the time the copy is prepared for this document, the University does not guarantee its accuracy. The University reserves the right to make changes in applicable regulations, policies, requirements, and other information contained in this document at any time without notice. CONTENTS Medical School Calendar........................................................................................................................................1 Essential Information for All Medical School Faculty, Staff, and Students Directory Information.......................................................................................................................................5 Consent to Use Photographic Images ...............................................................................................................5 Stanford University ID Number .......................................................................................................................6 SUNet ID ..........................................................................................................................................................6 Identification Cards ..........................................................................................................................................6 -

Download 2020-2021 Handbook

Stanford Biosciences Student Association Student Handbook 2020-2021 SBSA Executive Board President Jason Rodencal | [email protected] President Candace Liu | [email protected] Vice President Edel McCrea | [email protected] Financial Officer Matine Azadian | [email protected] Communications Brenda Yu | [email protected] CGAP Representative Lucy Xu | [email protected] Website: sbsa.stanford.edu Facebook: facebook.com/SBSAofficial Twitter: twitter.com/SBSA_official Instagram: instagram.com/SBSA_official Contents Welcome! Home Program representation in SBSA Other awesome SBSA activities BioAIMS Li Ka Shing Center for Learning and Knowledge (LKSC) Navigating graduate school Advice for starting graduate students: choosing a lab Advice for starting graduate students: being successful Career Mentoring Stanford opportunities and resources Fellowships Outreach Campus Involvement Professional Development Teaching Writing Sports Useful Stanford websites Offices General Racial Justice Resources Finances Mind over Money National Science Foundation Fellowships Estimated Taxes Banking Emergency Aid and Special Grants Housing Sticker shock Apply for on campus or off campus housing Family housing: what if I have a spouse or partner and/ or children? Deadlines Have roommates Living off-campus: how to find housing Living off-campus: transportation options Statement of support letter from your department Credit score Pets Transportation Transportation at Stanford Getting Around Campus Getting Around the Bay Getting to the Airport Shopping needs Shopping Malls Bed Linens and Housewares Grocery Stores Farmers Markets Electronics Office Supplies Last updated: June 30, 2020 2 | SBSA Handbook 2020-2021 Welcome! The Stanford Biosciences Student Association (SBSA) would like to welcome you to graduate school and to the Stanford community! SBSA is a student-run organization that serves and represents graduate students from biology-related fields in the School of Medicine, the School of Humanities and Sciences, and the School of Engineering. -

Libraries and Computing Resources 1

Libraries and Computing Resources 1 The J. Henry Meyer Memorial Library houses the East Asia Library as LIBRARIES AND COMPUTING well as the Academic Computing Services group of SULAIR and provides study, multimedia, consulting, and instructional support services. In addition, Meyer Library houses the University's Digital Language Lab, RESOURCES technology enabled study spaces and classrooms, the Academic Technology Lab, and the central offices of Student Computing and Stanford University Libraries and Academic Computing Services. Academic Information Resources Branch Libraries University Librarian and Director of Academic Information Resources: Humanities and Social Sciences Branch Libraries include the Art and Michael A. Keller Architecture Library, Cubberley Education Library, East Asia Library, Music Web Site: http://library.stanford.edu (http://library.stanford.edu/) Library, and Archive of Recorded Sound. Stanford University Libraries and Academic Information Resources Science Branch Libraries include the Branner Earth Sciences Library, (SULAIR) includes more than 30 libraries and programs supporting Engineering Library, Falconer Biology Library, Mathematical and research, teaching, and learning at Stanford University. SULAIR acquires Computer Sciences Library, Harold A. Miller Library at the Hopkins Marine and delivers library collections in all formats, establishes policies and Station, Physics Library, and Swain Library of Chemistry and Chemical standards to guide the use of academic information resources, develops Engineering. training and support programs for academic uses of computers, and maintains a broad array of electronic information resources, including the For a complete list of campus libraries, see the Libraries and Collections online library catalog and several hundred article and indexing databases (http://libraries.stanford.edu) web site. and electronic journal subscriptions. -

Emeriti Privilegesbenefits May 2021

Stanford University Privileges and Benefits for Emeriti/ae Faculty Our faculty are at the heart of the intellectual life of our university, and I want to personally thank you as Stanford emeriti/ae for your service to the University. Throughout your careers, you have educated new generations of students, advanced discovery, and applied knowledge in world- changing ways. We are incredibly proud of your remarkable accomplishments, and we are grateful for your ongoing involvement with the Stanford community. President Marc Tessier-Lavigne SUNet ID As a Stanford University emeritus/a faculty member, you are eligible for a "regular" SUNet ID, free of charge. A SUNet ID identifies you as a current member of the Stanford community. You have the privilege to use computer resources and support, email services, web pages, etc., and your SUNet ID will identify you to those services. You can also access dial-in services, file servers, and site-licensed software. For information or assistance with your SUNet ID, contact the IT Service Desk at (650) 725-4357 (5-HELP), visit the website at: http://sunetid.stanford.edu or submit a HelpSU ticket at: https://stanford.service-now.com/services?id=get_help Stanford ID Card When you retire you should obtain a new emeritus/a ID card at the ID Card Office. The ID Card Office is located in the Student Services Center (second floor of Tresidder). Their contact number is (650) 725-2434. Please be sure to bring identification with you (e.g., a driver's license). There is no charge for your new emeritus/a ID card. -

Table of Contents

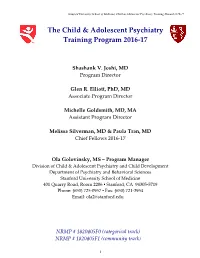

Stanford University School of Medicine, Child & Adolescent Psychiatry Training Manual 2016-17 The Child & Adolescent Psychiatry Training Program 2016-17 Shashank V. Joshi, MD Program Director Glen R. Elliott, PhD, MD Associate Program Director Michelle Goldsmith, MD, MA Assistant Program Director Melissa Silverman, MD & Paula Tran, MD Chief Fellows 2016-17 Ola Golovinsky, MS – Program Manager Division of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry and Child Development Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Stanford University School of Medicine 401 Quarry Road, Room 2206 ▪ Stanford, CA 94305-5719 Phone: (650) 725-0957 ▪ Fax: (650) 721-3954 Email: [email protected] NRMP # 1820405F0 (categorical track) NRMP # 1820405F1 (community track) 1 Stanford University School of Medicine, Child & Adolescent Psychiatry Training Manual 2016-17 Introduction The Mission of the Stanford Division of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry and Child Development is to provide leadership in the field of child and adolescent mental health by integrating clinical practice, teaching, and research. We are dedicated to: • Providing state-of-the-art patient care • Training future professionals in child psychiatry and psychology • Advancing knowledge in: o Neuroscience o Understanding of pathogenesis o Interactions between biology and environment o Integrated treatment and outcomes o Prevention The highest priority of the Training Program in Child & Adolescent Psychiatry at Stanford University is to prepare trainees for leadership roles in academic child & adolescent psychiatry, clinical practice and public service. Regardless of their career choices, we believe that all trainees must be thoroughly trained, first and foremost, as clinicians. The Stanford training program is based on the principles of developmental sciences and developmental psychopathology. This theoretical framework views human development and its disturbances as flowing from the complex and reciprocal interactions between biology, the family, and the broader social, physical and cultural environments. -

Stanford University Architectural Drawings Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt309nf3b1 No online items Guide to the Stanford University Architectural Drawings Collection compiled by University Archives staff Stanford University LibrariesDepartment of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford, California October 2010 Copyright © 2010 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Guide to the Stanford University SUARCH 1 Architectural Drawings Collection Overview Call Number: SUARCH Title: Stanford University architectural drawings collection Dates: 1889-1965, undated Physical Description: 2522 Items Summary: The materials consist of architectural drawings of Stanford University buildings and grounds. Language(s): In English. Repository: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford University Libraries 557 Escondido Mall Stanford, CA 94305-6064 Email: [email protected] Phone: (650) 725-1022 URL: http://www-sul.stanford.edu/depts/spc/spc.html Information about Access The materials are open for research use. Ownership & Copyright All requests to reproduce, publish, quote from, or otherwise use collection materials must be submitted in writing to the University Archivist, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California 94304-6064. Consent is given on behalf of University Archives as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission from the copyright owner. Such permission must be obtained from the copyright owner, heir(s) or assigns. See: http://library.stanford.edu/depts/spc/pubserv/permissions.html. Restrictions also apply to digital representations of the original materials. Use of digital files is restricted to research and educational purposes. Scope and Contents note The materials consist of architectural drawings of Stanford University buildings and grounds. Arrangement note The materials are arranged by building. -

Table of Contents

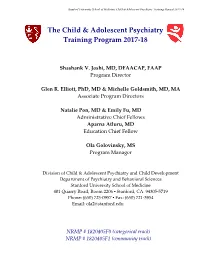

Stanford University School of Medicine, Child & Adolescent Psychiatry Training Manual 2017-18 The Child & Adolescent Psychiatry Training Program 2017-18 Shashank V. Joshi, MD, DFAACAP, FAAP Program Director Glen R. Elliott, PhD, MD & Michelle Goldsmith, MD, MA Associate Program Directors Natalie Pon, MD & Emily Fu, MD Administrative Chief Fellows Aparna Atluru, MD Education Chief Fellow Ola Golovinsky, MS Program Manager Division of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry and Child Development Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Stanford University School of Medicine 401 Quarry Road, Room 2206 ▪ Stanford, CA 94305-5719 Phone: (650) 725-0957 ▪ Fax: (650) 721-3954 Email: [email protected] NRMP # 1820405F0 (categorical track) NRMP # 1820405F1 (community track) Stanford University School of Medicine, Child & Adolescent Psychiatry Training Manual 2017-18 Introduction The Mission of the Stanford Division of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry and Child Development is to provide leadership in the field of child and adolescent mental health by integrating clinical practice, teaching, and research. We are dedicated to: • Providing state-of-the-art patient care • Training future professionals in child psychiatry and psychology • Advancing knowledge in: o Neuroscience o Understanding of pathogenesis o Interactions between biology and environment o Integrated treatment and outcomes o Prevention The highest priority of the Training Program in Child & Adolescent Psychiatry at Stanford University is to prepare trainees for leadership roles in academic child & adolescent psychiatry, clinical practice and public service. Regardless of their career choices, we believe that all trainees must be thoroughly trained, first and foremost, as clinicians. The Stanford training program is based on the principles of developmental sciences and developmental psychopathology. -

J. E. Wallace Sterling, President of Stanford University, Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt587037x1 No online items Guide to the J. E. Wallace Sterling, President of Stanford University, Papers compiled by Daniel Hartwig Stanford University Libraries.Dept. of Special Collections & University Archives. Stanford, California 1990 Copyright © 2013 The Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. Note This encoded finding aid is compliant with Stanford EAD Best Practice Guidelines, Version 1.0. Guide to the J. E. Wallace SC0216 1 Sterling, President of Stanford University, Papers Overview Call Number: SC0216 Creator: Sterling, J. E. Wallace, (John Ewart Wallace), 1906-1985 Title: J. E. Wallace Sterling, president of Stanford University, papers Dates: 1913-1969 Bulk Dates: 1949-1969 Physical Description: 300 Linear feet Summary: Papers primarily represent Sterling's years as President of Stanford University and include correspondence, memoranda, proposals, speeches, minutes, reports, budgets, clippings, and legal papers. Language(s): The materials are in English. Repository: Dept. of Special Collections & University Archives. Stanford University Libraries. 557 Escondido Mall Stanford, CA 94305 Email: [email protected] Phone: (650) 725-1022 URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Information about Access Collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least 24 hours in advance of intended use. Ownership & Copyright All requests to reproduce, publish, quote from, or otherwise use collection materials must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California 94304-6064. Consent is given on behalf of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission from the copyright owner. -

For List of Holdings Consult the Serial Record 0001-0099 HISTORY of the FOUNDERS Call No. Title 0001-0023 Leland Stanford 0001

0001-0099 HISTORY OF THE FOUNDERS Call No. Title 0001-0023 Leland Stanford 0001 Stanford Family Scrapbooks - NOW SC 33F 0002 *Biographical Material (by date, then by author) 0003 Essays, class papers re: Leland Stanford 0004 0005 0006 Properties and Residences (alphabetically arranged) [place] 0006 Michigan Bluff MICH 0006 Palo Alto Home PALO 0006 Palo Alto Stock Farm, includes horse studies PASF -Muybridge, Eadweard SEE 9820 *-Coutts Ranch SEE ALSO SC 202 -Dennis Martin, Church and Cemetery -Domingo Grosso ("The Hermit") -Gordon Estate -Certificate of breeding and transfer -Vineyard label 0006 Sacramento House [feasibility study made by Dept. of Parks and SACR Recreation in 1964] 0006 San Francisco House SANF 0006 Vina Ranch VINA -Vina Invoice 0006 Warm Springs Ranch WARM * for list of holdings consult the serial record Call No. Title 0001-0099: HISTORY OF THE FOUNDERS 0001-0023 Leland Stanford (cont.) 0006 Washington, D.C. House WASH -1701 K (leased) 0006/9 Miscellaneous Properties (incl. carriages) 0007 0008 0009 0010-0014 Railroad [general] 0010 Legal Suits, miscellaneous (arranged by date) Articles re. participation in Railroad Affairs The "Governor Stanford" Locomotive William Herrin, Vice President and Chief Counsel of the Southern Pacific Co. -Family Mementos 0011 0013 Other Railroad Associates [alphabetical by name] Crocker, Charles (CROC) Herrin, William Hewes, David (HEWE) Hopkins, Mark (HOPK) Sargent, Aaron 0014 CPRR [empty] SP [empty] 0015 Other business enterprises *Insurance *Mining *Shipping incomplete -Occidental and Oriental Steamship Company *one not in the file *California Street Cable Railroad, S.F. 0016 0017 * for list of holdings consult the serial record Call No. Title 0001-0099: HISTORY OF THE FOUNDERS 0001-0023 Leland Stanford (cont.) 0018 0019 0020 Politics speeches interviews 0020/4 Writings about 0021 0022 Stanford family genealogy Stanford, Arthur Willis.