Protestant Ecumenism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aspects of Sport and American Imperialism Gerald R

Aspects of sport and american imperialism Gerald R. Gems North Central College Naperville, Il. USA The United States has been engaged in an imperialist venture since its early colonization by British settlers in the seventeenth century. White, Anglo-Saxon Protestants continually moved westward thereafter until they had conquered all the indigenous tribes and Mexican lands to control the North American continent. At the end of the nineteenth century the United States moved to extend its reach to global proportions with an overseas empire acquired through victory in the Spanish-American War. While religion, race, and commerce were primary factors in the United States' quest to fulfill its "Manifest Destiny," sport proved a more subtle means of inculcating American cultural values in subject populations in the Pacific and Caribbean regions. That process started in the 1820s in Hawaii when American missionaries forbade the popular recreations and gambling practices of the native residents. They housed native children in residential schools and taught them to play baseball. A similar procedure was followed to assimilate conquered Native American tribes and European immigrant groups throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The use of sport as a tool of acculturation reached its zenith in the colonial administration of the Philippines, where sport assumed a comprehensive and nationalistic role in combating the imperial ambitions of Japan in the Pacific. Throughout Asia and the Caribbean the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) endeavored to spread its religious message and the adoption of American games such as basketball and volleyball. The YMCA brought its racial segregation practices along with the American sport forms to the American colonies. -

Cradle of Airpower an Illustrated History of Maxwell Air Force Base 1918–2018

Cradle of Airpower An Illustrated History of Maxwell Air Force Base 1918–2018 Jerome A. Ennels Sr. Robert B. Kane Silvano A. Wueschner Air University Press Curtis E. LeMay Center for Doctrine Development and Education Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama Chief of Staff, US Air Force Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gen David L. Goldfein Names: Ennels, Jerome A., 1950– author. | Kane, Robert B., 1951– author. | Commander, Air Education and Training Wueschner, Silvano A. (Silvano Alfons), 1950– author. | Air University (U.S.). Press, Command publisher. Lt Gen Steven L. Kwast Title: Cradle of aerospace education : an illustrated history of Maxwell Air Force Base, 1918- 2018 / Jerome A. Ennels, Robert B. Kane, Silvano A. Wueschner. Commander and President, Air University Other titles: Illustrated history of Maxwell Air Force Base, 1918–2018 Lt Gen Anthony J. Cotton Description: First edition. | Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama : Air University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Commander, Curtis E. LeMay Center for Identifiers: LCCN 2018047340 | ISBN 9781585662852 Doctrine Development and Education Subjects: LCSH: Maxwell Air Force Base (Ala.)—History. | Air bases—Alabama— Maj Gen Michael D. Rothstein Montgomery County—History. | Air power—United States—History. | Military education—United States—History. | Air University (U.S.)—History. | United States. Air Director, Air University Press Force—History. Dr. Ernest Allan Rockwell Classification: LCC UG634.5.M35 E55 2018 | DDC 358.4/17/0976147–dc23 | SUDOC D 301.26/6:M 45/3 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018047340 Project Editor Donna Budjenska Cover Art, Book Design, and Illustrations Daniel Armstrong Composition and Prepress Production Nedra Looney Published by Air University Press in October 2018 Print Preparation and Distribution Diane Clark Air University Press 600 Chennault Circle, Bldg. -

20Th Century Theology and NT Studies As Any Other Thinker B

TWENTIETH CENTURY I. Afterglow of the Golden Age of Missions A. Student Volunteer Movement 1. Formed by Moody and the YMCA in 1886 to recruit energetic, idealistic, and skilled laborers for the foreign fields; John Mott takes the helm in 1888 2. Themes: “Make Jesus King;” “The Evangelization of the World in Our Generation” 3. Declining by WWII and defunct by 1969, ultimately 20,000 of its members head for the mission field, e.g., William Borden of Yale B. Edinburgh Missionary Conference of 1910 and the beginnings of the Ecumenical Movement 1. Called to address the challenges of modern missions through greater cooperation of missionary agencies and churches 2. Key leaders a. John R. Mott 1) American Methodist layman and experienced ecumenical leader; had served as secretary of the Int’l Committee of the YMCA from age 23, as well as General Secretary of the World’s Student Christian Federation 2) Founded the International Missionary Council in 1921 after the war 3) Chairing the “Continuation Committee” of the Edinburgh Conference, Mott would spearhead the founding of the WCC b. Charles Brent (d. 1929) 1) Canadian Anglican missionary to Philippines 2) With the support of N.American Anglicans, he called for a worldwide “Faith and Order” Conference to discuss closer cooperation (and possible merger) of church bodies (a) WWI postponed the first conference till 1927, Lausanne, Switzerland (b) As the conference name implies, Brent’s basis of unity would be through agreement in the broader areas of creed and practice which the churches held in common (c) Significantly, the 1974 International Congress on World Evangelization was also held in Lausanne c. -

FALCON V, LLC, Et Al., DEBTORS. CHAPTER 11

Case 19-10547 Doc 275 Filed 07/03/19 Entered 07/03/19 14:06:14 Page 1 of 1 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA IN RE: CHAPTER 11 FALCON V, L.L.C., et al.,1 CASE NO. 19-10547 DEBTORS. JOINTLY ADMINISTERED CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE Attached hereto is the Affidavit of Service of Winnie Yeung of Donlin, Recano & Company, Inc. (the “Affidavit”) which declares that a copy of the Notice to Holders of Claims Against Debtor of the Bar Dates for Filing Proofs of Claim and Proof of Claim and Instructions was served on the parties listed in Exhibit 3 to the Affidavit on July 3, 2019. Dated: July 3, 2019 Respectfully submitted, KELLY HART PITRE /s/ Rick M. Shelby Patrick (Rick) M. Shelby (#31963) Louis M. Phillips (#10505) Amelia L. Bueche (#36817) One American Place 301 Main Street, Suite 1600 Baton Rouge, LA 70801-1916 Telephone: (225) 381-9643 Facsimile: (225) 336-9763 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Counsel for the Debtors 1 The “Debtors” are the following entities (the corresponding bankruptcy case numbers follow in parentheses): Falcon V, L.L.C. (Case No. 19-10547), ORX Resources, L.L.C. (Case No. 19-10548), and Falcon V Holdings, L.L.C. (Case No. 19-10561). The address of the Debtors is 400 Poydras Street, Suite 1100, New Orleans, Louisiana 70130. 1 Case 19-10547 Doc 275-1 Filed 07/03/19 Entered 07/03/19 14:06:14 Page 1 of 295 Case 19-10547 Doc 275-1 Filed 07/03/19 Entered 07/03/19 14:06:14 Page 2 of 295 . -

American Colonial Culture in the Islamic Philippines, 1899-1942

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 2-1-2016 12:00 AM Civilizational Imperatives: American Colonial Culture in the Islamic Philippines, 1899-1942 Oliver Charbonneau The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Frank Schumacher The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Oliver Charbonneau 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Asian History Commons, Cultural History Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Charbonneau, Oliver, "Civilizational Imperatives: American Colonial Culture in the Islamic Philippines, 1899-1942" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3508. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3508 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Abstract and Keywords This dissertation examines the colonial experience in the Islamic Philippines between 1899 and 1942. Occupying Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago in 1899, U.S. Army officials assumed sovereignty over a series of Muslim populations collectively referred to as ‘Moros.’ Beholden to pre-existing notions of Moro ungovernability, for two decades military and civilian administrators ruled the Southern Philippines separately from the Christian regions of the North. In the 1920s, Islamic areas of Mindanao and Sulu were ‘normalized’ and haphazardly assimilated into the emergent Philippine nation-state. -

Pushing at the Boundaries of Unity Anglicans and Baptists in Conversation Pushing Boundaries 30/9/05 13:20 Page Ii Pushing Boundaries 30/9/05 13:20 Page Iii

Pushing boundaries 30/9/05 13:20 Page i pushing at the boundaries of unity Anglicans and Baptists in conversation Pushing boundaries 30/9/05 13:20 Page ii Pushing boundaries 30/9/05 13:20 Page iii pushing at the boundaries of unity Anglicans and Baptists in conversation Faith and Unity Executive Committee of the Baptist Union of Great Britain The Council for Christian Unity of the Church of England Pushing boundaries 30/9/05 13:20 Page iv Church House Publishing All rights reserved. No part Church House of this publication may be Great Smith Street reproduced or stored or London SW1P 3NZ transmitted by any means or in any form, electronic Tel: 020 7898 1451 or mechanical, including Fax: 020 7898 1449 photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system without written ISBN 0 7151 4052 3 permission which should be sought from the Copyright GS Misc 801 Administrator, Church House Publishing, Church House, A report of the informal Great Smith Street, London conversations between the Council SW1P 3NZ. for Christian Unity of the Church of Email: [email protected]. England and the Faith and Unity Executive of the Baptist Union of Great Britain This report has only the authority of the commission that prepared it. Published 2005 for the Council for Christian Unity of the Archbishops’ Council and the Baptist Union of Great Britain by Church House Publishing Copyright © The Archbishops’ Council and the Baptist Union of Great Britain 2005 Typeset in Franklin Gothic 9.5/11pt Printed in England by The Cromwell Press Ltd, -

March Newsletter 2021

INTERNATIONAL DIOCESE/ACNA Saint Peter’s Anglican Church MARCH 2021 FORWARD, ALWAYS FORWARD, EVERYWHERE FORWARD MONTHLY CALENDARST. PETER’S KEY MARCH GORDON T. GODLY 3 – Lenten Bible Study 7PM Zoom 1919 - 2021 4 – Study-Prayer Group 7AM Zoom Gordon Thomas Godly of Ft. Collins, CO, passed away 5 – Taize Prayer Service 7PM 6 - Teen Group 6PM Peacefully, early on February 1st, at home. He was 101 years old. Gordon was a remarkable man who lived an 7 – 3rd Sunday Lent 9 & 10:30 AM extraordinary life and he will be missed by his children, 7 – Catechism Class 6PM grandchildren, friends 10 – Lenten Bible Study 7PM Zoom and his parish church of St Peter’s. Gordon was born in Woodbastwick, Norfolk County, England in 1919. His 11 – Study-Prayer Group 7AM Zoom 13 - Teen Group 6PM education was interrupted by service in the British Army for seven years 14 - 3rd Sunday Lent 9 & 10:30 AM during World War II. He enjoyed regaling his family and friends with stories 14 - Catechism Class 6PM from his Army postings in England, North Africa and Australia. At the time of 17 - Lenten Bible Study 7PM Zoom his discharge in 1946 he was an acting major in the Intelligence Corps. After the war, he continued his studies at Birkbeck College, Univ. of London. He 18 – Study-Prayer Group 7AM Zoom 18 - Vestry Meeting 7PM on Zoom became a research chemist with an English company which eventually brought Gordon to New York with his wife and young family. A few years 19 – Zeteo Box Packing Church 1PM 19 - Taize Prayer Service 7PM later they moved to Matawan, NJ where he was a very active member of 20 - Teen Group 6PM Trinity Episcopal Church and served as a lay reader. -

Timothy Marr1 DIASPORIC INTELLIGENCES in THE

Mashriq & Mahjar 2, no. 1 (2014), 78-106 ISSN 2169-4435 Timothy Marr1 DIASPORIC INTELLIGENCES IN THE AMERICAN PHILIPPINE EMPIRE: THE TRANSNATIONAL CAREER OF DR. NAJEEB MITRY SALEEBY Abstract This article assesses the complex career of Najeeb Saleeby (1870-1935): a Lebanese Protestant physician who became naturalized as a U.S. citizen while serving the American colonial occupation of the Philippines. Saleeby was valued as a cultural intermediary whose facility with Arabic and Islam empowered his rise as the foremost American expert on the Muslim Moros of the southern Islands of Mindanao and Sulu. Saleeby’s story dramatizes the political advancement possible for an educated “Syrian” who aligned his mission with the American “duty” of teaching self-government to the Filipinos. However, his own background as a migrant from Asia and his sympathy for Moro history and Figure 1: Najib Saleeby culture raised unfair suspicions about his ultimate allegiance. Dr. Saleeby never settled in the United States but dedicated his whole career to the welfare of the Filipino peoples through his medical profession, his post-colonial advocacy for bilingual education, and his criticism of how imperialism compromised American democracy. INTRODUCTION In 2004 the meeting ground in the U.S. Embassy in Manila was dedicated the “Najeeb Saleeby Courtyard” in honor of a muhajir from Beirut who, after Timothy Marr is the Bowman and Gordon Gray Distinguished Term Associate Professor of American Studies, UNC Chapel Hill; Email: [email protected] Diasporic Intelligences 79 beginning the process of becoming naturalized as an American citizen, moved to the Philippines in 1901 under the auspices of the United States military occupation of the Islands.2 That Saleeby’s name was commemorated at the transcultural crossroads of U.S. -

General Leonard Wood and the US Army in the Southern

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 5-6-2013 “The Right Sort of White Men”: General Leonard Wood and the U. S. Army in the Southern Philippines, 1898-1906 Omar H. Dphrepaulezz University of Connecticut, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Dphrepaulezz, Omar H., "“The Right Sort of White Men”: General Leonard Wood and the U. S. Army in the Southern Philippines, 1898-1906" (2013). Doctoral Dissertations. 59. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/59 “The Right Sort of White Men”: General Leonard Wood and the U. S. Army in the Southern Philippines, 1898-1906 Omar Hassan Dphrepaulezz University of Connecticut, 2013 This dissertation examines an encounter with the Muslim world within the context of U.S. overseas expansion from 1898 to 1906 and the transformation of white masculinity in the United States from the 1870s to the 1920s. In 1906, in the southernmost portion of the Philippines, the U.S. military encountered grassroots militant resistance. Over one thousand indigenous Muslim Moros on the island of Jolo, in the Sulu archipelago, occupied a dormant volcanic crater and decided to oppose American occupation. This meant defying their political leaders, who accommodated the Americans. These men and women, fighting in the defense of Islamic cultural and political autonomy, produced the spiritual, intellectual, and ideological justification for anti-imperial resistance. In this dissertation, I examine how underlying cultural assumptions and categories simplified definitions of race and gender so that American military officials could justify the implementation of U.S. -

Devoted-To-Prayer-2021-2022.Pdf

Devoted to PRAYER 2021-2022 DA I LY P R AY E R AND READING CALENDAR This daily prayer and Bible reading guide,Devoted to Prayer (based on Acts 2:42), was conceived and prepared by the Rev. Andrew S. Ames Fuller, director of communications for the North American Lutheran Church (NALC). After a challenging year in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, we have been provided with a unique opportunity to revitalize the ancient practice of daily prayer and Scripture reading in our homes. While the Reading the Word of God three-year lectionary provided a much-needed and refreshing calendar for our congregations to engage in Scripture reading, this calendar includes a missing component of daily devotion: prayer. This guide is to provide the average layperson and pastor with the simple tools for sorting through the busyness of their lives and reclaiming an act of daily discipleship with their Lord. The daily readings follow theLutheran Book of Worship two-year daily lectionary, which reflect the church calendar closely. The commemorations are adapted from Philip H. Pfatteicher’s New Book of Festivals and Commemorations, a proposed common calendar of the saints that builds from the Lutheran Book of Worship, but includes saints from many of those churches in ecumenical conversation with the NALC. The introductory portion is adapted from Christ Church (Plano)’s Pray Daily. Our hope is that this calendar and guide will provide new life for congregations learning and re-learning to pray in the midst of a difficult and changing world. A GUIDE FOR DAILY PRAYER Introduction • Memorize the PSALMS and CANTICLES. -

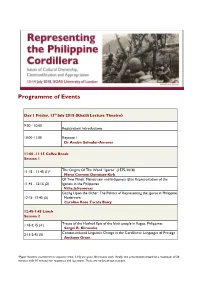

Programme of Events

Programme of Events th Day 1 Friday, 13 July 2018 (Khalili Lecture Theatre) 9:00 - 10:00 Registration/ Introductions 10:00-11:00 Keynote 1 Dr Analyn Salvador-Amores 11:00 -11:15 Coffee Break Session 1 11:15 - 11:45 (1)* The Origins Of The Word “Igorot” (1575-2018) Maria Carmen Domingo-Kirk Of Two Minds: Mainstream and Indigenous Elite Representation of the 11:45 - 12:15 (2) Igorots in the Philippines Villia Jefremovas Gazing Upon the Other: The Politics of Representing the Igorot in Philippine 12:15- 12:45 (3) Modernism Caroline Rose Tacata Baicy 12:45-1:45 Lunch Session 2 1:45-2:15 (4 ) Traces of the Hudhud Epic of the Itkak people in Ifugao, Philippines Sergei B. Klimenko 2:15-2:45 (5) Contact-induced Linguistic Change in the Cordilleras: Languages of Prestige Anthony Grant *Paper Readers (numbered in sequence from 1-15) are given 30 minutes each. Ideally, the presentation should be a maximum of 20 minutes with 10 minutes for responses and questions. There are no break-out sessions. 2:45-3:15 (6) Miscellaneous Assemblages: An overview of the Philippine collections in the Horniman Museum Fiona Kerlogue 3:15- 4:00 Networking/ Brief Intro to Philippine Studies at SOAS/Coffee Break Session 3 4:00-4:30 (7) Revisiting Ethno-historical Events and Issues in Benguet Cordillera History June Chayapan Prill-Brett 4:30-5:00 (8) Head-hunters Under The Stars And Stripes: Revisiting Colonial Historiography Richard G. Scheerer, M.D. Short Films 5:00-6:00 "Dugo at Tinta" (Blood + Ink) Jill Damatac Futter (15 minutes) "Am-Amma" (The -

Views on Morality and Vice, and His Belief in Responsibility

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2016 Savior from Civilization: Charles Brent, Episcopal Bishop to the Philippine Islands, and the Role of Religion in American Colonialism, 1901-1918 Jason C. Ratcliffe Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES SAVIOR FROM CIVILIZATION: CHARLES BRENT, EPISCOPAL BISHOP TO THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS, AND THE ROLE OF RELIGION IN AMERICAN COLONIALISM, 1901-1918 By JASON RATCLIFFE A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2016 Jason Ratcliffe defended this thesis on November 16, 2016. The members of the supervisory committee were: G. Kurt Piehler Professor Directing Thesis Claudia Liebeskind Committee Member Michael Creswell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii This is dedicated to Alli, kinsa’y milagro nako, akong gugma, ug ang tagbantay sa akong kasingkasing, hangtud sa hangtud. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................................................................v INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1