Diagnosing and Treating Onychomycosis Nardo Zaias, Ml); Brad Glick, DO, MPH; and Gerbert Rebell, MS Miami Bench, Florida

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fungal Infections from Human and Animal Contact

Journal of Patient-Centered Research and Reviews Volume 4 Issue 2 Article 4 4-25-2017 Fungal Infections From Human and Animal Contact Dennis J. Baumgardner Follow this and additional works at: https://aurora.org/jpcrr Part of the Bacterial Infections and Mycoses Commons, Infectious Disease Commons, and the Skin and Connective Tissue Diseases Commons Recommended Citation Baumgardner DJ. Fungal infections from human and animal contact. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2017;4:78-89. doi: 10.17294/2330-0698.1418 Published quarterly by Midwest-based health system Advocate Aurora Health and indexed in PubMed Central, the Journal of Patient-Centered Research and Reviews (JPCRR) is an open access, peer-reviewed medical journal focused on disseminating scholarly works devoted to improving patient-centered care practices, health outcomes, and the patient experience. REVIEW Fungal Infections From Human and Animal Contact Dennis J. Baumgardner, MD Aurora University of Wisconsin Medical Group, Aurora Health Care, Milwaukee, WI; Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI; Center for Urban Population Health, Milwaukee, WI Abstract Fungal infections in humans resulting from human or animal contact are relatively uncommon, but they include a significant proportion of dermatophyte infections. Some of the most commonly encountered diseases of the integument are dermatomycoses. Human or animal contact may be the source of all types of tinea infections, occasional candidal infections, and some other types of superficial or deep fungal infections. This narrative review focuses on the epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis and treatment of anthropophilic dermatophyte infections primarily found in North America. -

Redalyc.Morphological Varieties of Trichophyton Rubrum Clinical Isolates

Revista Mexicana de Micología ISSN: 0187-3180 [email protected] Sociedad Mexicana de Micología México Hernández-Hernández, Francisca; Manzano-Gayosso, Patricia; Córdova-Martínez, Erika; Méndez- Tovar, Luis Javier; López-Martínez, Rubén; García de Acevedo, Beatriz; Orozco-Topete, Rocío; Cerbón, Marco Antonio Morphological varieties of Trichophyton rubrum clinical isolates Revista Mexicana de Micología, núm. 25, diciembre, 2007, pp. 9-14 Sociedad Mexicana de Micología Xalapa, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=88302504 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Morphological varieties of Trichophyton rubrum clinical isolates Francisca Hernández-Hernández 1, Patricia Manzano-Gayosso1, Erika Córdova-Martínez1, Luis Javier Méndez-Tovar2, Rubén López-Martínez1, Beatriz García de Acevedo3, Rocío Orozco-Topete3, Marco Antonio Cerbón4 1 Departamento de Microbiología y Parasitología, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. 2Servicio de Dermatología y Micología, Centro Médico Nacional (CMN) Siglo XXI, IMSS. 3Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición “Salvador Zubirán”. 4Departamento de Biología, Facultad de Química, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México, D. F., México 7 0 Variedades morfológicas de aislamientos clínicos de Trichophyton rubrum 0 2 , 4 1 Resumen. Trichophyton rubrum es el dermatofito antropofílico causante de micosis - 9 superficiales aislado con mayor frecuencia en todo el mundo. Diversas variedades : 5 2 morfológicas de este dermatofito han sido reportadas, lo cual en algunas ocasiones hace A Í difícil su identificación. Nuestro objetivo fue identificar y determinar la frecuencia de G O variedades morfológicas entre los aislados de T. -

NEWSLETTER 2017•Issue 2

NEWSLETTER 2017•Issue 2 page 2 Deep dermatophytosis page 4 Deep dermatophytosis: A case report page 5 Fereydounia khargensis: A new and uncommon opportunistic yeast from Malaysia page 6 Itraconazole: A quick guide for clinicians Visit us at AFWGonline.com and sign up for updates Editors’ welcome Dr Mitzi M Chua Dr Ariya Chindamporn Adult Infectious Disease Specialist Associate Professor Associate Professor Department of Microbiology Department of Microbiology & Parasitology Faculty of Medicine Cebu Institute of Medicine Chulalongkorn University Cebu City, Philippines Bangkok, Thailand This year we celebrate the 8th year of AFWG: 8 years of pursuing excellence in medical mycology throughout the region; 8 years of sharing expertise and encouraging like-minded professionals to join us in our mission. We are happy to once again share some educational articles from our experts and keep you updated on our activities through this issue. Deep dermatophytosis may be a rare skin infection, but late diagnosis or ineffective treatment may lead to mortality in some cases. This issue of the AFWG newsletter focuses on this fungal infection that usually occurs in immunosuppressed individuals. Dr Pei-Lun Sun takes us through the basics of deep dermatophytosis, presenting data from published studies, and emphasizes the importance of treating superficial tinea infections before starting immunosuppressive treatment. Dr Ruojun Wang and Professor Ruoyu Li share a case of deep dermatophytosis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. In this issue, we also feature a new fungus, Fereydounia khargensis, first discovered in 2014. Ms Ratna Mohd Tap and Dr Fairuz Amran present 2 cases of F. khargensis and show how PCR sequencing is crucial to correct identification of this uncommon yeast. -

Molecular Analysis of Dermatophytes Suggests Spread of Infection Among Household Members

Molecular Analysis of Dermatophytes Suggests Spread of Infection Among Household Members Mahmoud A. Ghannoum, PhD; Pranab K. Mukherjee, PhD; Erin M. Warshaw, MD; Scott Evans, PhD; Neil J. Korman, MD, PhD; Amir Tavakkol, PhD, DipBact Practice Points When a patient presents with tinea pedis or onychomycosis, inquire if other household members also have the infection, investigate if they have a history of concomitant tinea pedis and onychomycosis, and examine for plantar scaling and/or nail discoloration. If the variables above areCUTIS observed, think about spread of infection and treatment options. Dermatophyte infection from the same strains may Drs. Ghannoum, Mukherjee, and Korman are from University be an important route for transmission of derma- Hospitals Case Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio. Dr. Warshaw is from the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and Minneapolis Veterans tophytoses within a household. In this study, we AffairsDo Medical Center. Dr. Evans is from Notthe Harvard School of Public used molecularCopy methods to identify dermatophytes Health, Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Tavakkol was from Novartis in members of dermatophyte-infected households Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, New Jersey, and and evaluated variables associated with the currently is from Topica Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Los Altos, California. spread of infection. Fungal species were identi- This article was supported by a grant from Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Dr. Ghannoum has served as a consultant and/or fied by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using speaker for and has received grants and contracts from Merck & Co, primers targeting the internal transcribed spacer Inc; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc; and Stiefel, (ITS) regions (ITS1 and ITS4). For strain differen- a GSK company. -

Dermatophyte and Non-Dermatophyte Onychomycosis in Singapore

Australas J. Dermatol 1992; 33: 159-163 DERMATOPHYTE AND NON-DERMATOPHYTE ONYCHOMYCOSIS IN SINGAPORE JOYCE TENG-EE LIM, HOCK CHENG CHUA AND CHEE LEOK GOH Singapore SUMMARY Onychomycosis is caused by dermatophytes, moulds and yeasts. It is important to identify the non-dermatophyte moulds as they are resistant to the usual anti-fungals. A prospective study was undertaken in the National Skin Centre, Singapore to study the pattern of dermatophyte and non-dermatophyte onychomycosis. 53 male and 47 female patients seen between June 1990 and June 1991 were entered into the study. Direct microscopy was done and the nail clippings were cultured. Toe and finger nails were equally infected. Dermatophytes were isolated from 21 patients namely, T. rubrum (12/21), T. interdigitale (5/21), T. mentagrophytes (3/21) and T. violaceum (1/21). Candida onychomycosis occurred in 39 patients and was caused by C. albicans (38/39) and C. parapsilosis (1/39). 37/39 patients had associated paronychia. 5 types of moulds were isolated from 12 patients, namely Fusarium species (6/12), Aspergillus species (3/12), S. brevicaulis (1/12), Aureobasilium species (1/12) and Penicillium species (1/12). Although the clinical pattern and microscopy may predict the type of organisms, in practice this is difficult. Only cultures were confirmatory. 28% (28/100) had negative cultures despite a positive microscopy, and moulds (12/100) grown might be contaminants rather than pathogens. Key words: Moulds, yeasts, fungi, tinea, onychomycosis, dermatophyte, non-dermatophyte INTRODUCTION METHODS AND MATERIALS Onychomycosis, a common nail disorder, is 100 consecutive patients, seen in our centre caused by dermatophytes, non-dermatophyte between June 1990 and June 1991, with a new moulds, or yeasts. -

Onychomycosis/ (Suspected) Fungal Nail and Skin Protocol

Onychomycosis/ (suspected) Fungal Nail and Skin Protocol Please check the boxes of the evaluation questions, actions and dispensing items you wish to include in your customized protocol. If additional or alternative products or services are provided, please include when making your selections. If you wish to include the condition description please also check the box. Description of Condition: Onychomycosis is a common nail condition. It is a fungal infection of the nail that differs from bacterial infections (often referred to as paronychia infections). It is very common for a patient to present with onychomycosis without a true paronychia infection. It is also very common for a patient with a paronychia infection to have secondary onychomycosis. Factors that can cause onychomycosis include: (1) environment: dark, closed, and damp like the conventional shoe, (2) trauma: blunt or repetitive, (3) heredity, (4) compromised immune system, (5) carbohydrate-rich diet, (6) vitamin deficiency or thyroid issues, (7) poor circulation or PVD, (8) poor-fitting shoe gear, (9) pedicures received in places with unsanitary conditions. Nails that are acute or in the early stages of infection may simply have some white spots or a white linear line. Chronic nail conditions may appear thickened, discolored, brittle or hardened (to the point that the patient is unable to trim the nails on their own). The nails may be painful to touch or with closed shoe gear or the nail condition may be purely cosmetic and not painful at all. *Ask patient to remove nail -

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis and Severe Asthma with Fungal Sensitisation

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis and Severe Asthma with Fungal Sensitisation Dr Rohit Bazaz National Aspergillosis Centre, UK Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust/University of Manchester ~ ABPA -a41'1 Severe asthma wl'th funga I Siens itisat i on Subacute IA Chronic pulmonary aspergillosjs Simp 1Ie a:spe rgmoma As r§i · bronchitis I ram une dysfu net Ion Lun· damage Immu11e hypce ractivitv Figure 1 In t@rarctfo n of Aspergillus Vliith host. ABP A, aHerg tc broncho pu~ mo na my as µe rgi ~fos lis; IA, i nvas we as ?@rgiH os 5. MANCHl·.'>I ER J:-\2 I Kosmidis, Denning . Thorax 2015;70:270–277. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206291 Allergic Fungal Airway Disease Phenotypes I[ Asthma AAFS SAFS ABPA-S AAFS-asthma associated with fu ngaIsensitization SAFS-severe asthma with funga l sensitization ABPA-S-seropositive a llergic bronchopulmonary aspergi ll osis AB PA-CB-all ergic bronchopulmonary aspergi ll osis with central bronchiectasis Agarwal R, CurrAlfergy Asthma Rep 2011;11:403 Woolnough K et a l, Curr Opin Pulm Med 2015;21:39 9 Stanford Lucile Packard ~ Children's. Health Children's. Hospital CJ Scanford l MEDICINE Stanford MANCHl·.'>I ER J:-\2 I Aspergi 11 us Sensitisation • Skin testing/specific lgE • Surface hydroph,obins - RodA • 30% of patients with asthma • 13% p.atients with COPD • 65% patients with CF MANCHl·.'>I ER J:-\2 I Alternar1a• ABPA •· .ABPA is an exagg·erated response ofthe imm1une system1 to AspergUlus • Com1pUcatio n of asthm1a and cystic f ibrosis (rarell·y TH2 driven COPD o r no identif ied p1 rior resp1 iratory d isease) • ABPA as a comp1 Ucation of asth ma affects around 2.5% of adullts. -

Managing Athlete's Foot

South African Family Practice 2018; 60(5):37-41 S Afr Fam Pract Open Access article distributed under the terms of the ISSN 2078-6190 EISSN 2078-6204 Creative Commons License [CC BY-NC-ND 4.0] © 2018 The Author(s) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 REVIEW Managing athlete’s foot Nkatoko Freddy Makola,1 Nicholus Malesela Magongwa,1 Boikgantsho Matsaung,1 Gustav Schellack,2 Natalie Schellack3 1 Academic interns, School of Pharmacy, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University 2 Clinical research professional, pharmaceutical industry 3 Professor, School of Pharmacy, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University *Corresponding author, email: [email protected] Abstract This article is aimed at providing a succinct overview of the condition tinea pedis, commonly referred to as athlete’s foot. Tinea pedis is a very common fungal infection that affects a significantly large number of people globally. The presentation of tinea pedis can vary based on the different clinical forms of the condition. The symptoms of tinea pedis may range from asymptomatic, to mild- to-severe forms of pain, itchiness, difficulty walking and other debilitating symptoms. There is a range of precautionary measures available to prevent infection, and both oral and topical drugs can be used for treating tinea pedis. This article briefly highlights what athlete’s foot is, the different causes and how they present, the prevalence of the condition, the variety of diagnostic methods available, and the pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of the -

P2399 Lateral Flow Immunoassay for Rapid Detection of Dermatophytes in Clinical Specimens

P2399 Lateral flow immunoassay for rapid detection of dermatophytes in clinical specimens Amanda Burnham-Marusich*1, Caitlyn Orne1 2, Alexander Kvam3, Heather Green2, Alexandra Myers4, Aline Rodrigues Hoffmann4, Amy Crum5, Mahmoud Ghannoun6, Thomas Kozel1 3 1DxDiscovery, Reno, United States, 2University of Nevada, Reno, Reno, United States, 3University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine, Reno, United States, 4Texas A&M University, College Station, United States, 5Houston SPCA, Houston, United States, 6Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, United States Background: Fungal skin infections affect approximately 1 billion people each year. Most infections are treated with topical antifungal agents. Other infections, e.g., tinea capitis and onychomycosis, require use of oral antifungal agents that may produce significant side effects in some patients. Laboratory confirmation of fungal infection prior to use of antifungal agents is recommended but often not done due, in part, to the time and cost of laboratory testing. The goal of this study was to develop a lateral flow immunoassay (LFIA) for rapid diagnosis of dermatophytosis. Materials/methods: Monoclonal antibody (mAb) 2DA6 was produced from splenocytes of mice immunized with fungal cell wall fragments. Hybridomas were generated using standard methods. Results: A LFIA was constructed from mAb 2DA6 for detection of mannans of dermatophyte fungi in clinical samples. The antibody is reactive with the alpha-1,6 mannose backbone in mannans of fungi of the Zygomycota and the Ascomycota. However, mAb 2DA6 has an exquisite sensitivity for mannans of dermatophytes and the Zygomycota due to an apparent low level of side chain substitution found on these mannans vs. high levels of side chain substitution that occludes the backbone in mannans of other fungi. -

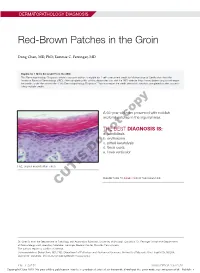

Red-Brown Patches in the Groin

DERMATOPATHOLOGY DIAGNOSIS Red-Brown Patches in the Groin Dong Chen, MD, PhD; Tammie C. Ferringer, MD Eligible for 1 MOC SA Credit From the ABD This Dermatopathology Diagnosis article in our print edition is eligible for 1 self-assessment credit for Maintenance of Certification from the American Board of Dermatology (ABD). After completing this activity, diplomates can visit the ABD website (http://www.abderm.org) to self-report the credits under the activity title “Cutis Dermatopathology Diagnosis.” You may report the credit after each activity is completed or after accumu- lating multiple credits. A 66-year-old man presented with reddish arciform patchescopy in the inguinal area. THE BEST DIAGNOSIS IS: a. candidiasis b. noterythrasma c. pitted keratolysis d. tinea cruris Doe. tinea versicolor H&E, original magnification ×600. PLEASE TURN TO PAGE 419 FOR THE DIAGNOSIS CUTIS Dr. Chen is from the Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia. Dr. Ferringer is from the Departments of Dermatology and Laboratory Medicine, Geisinger Medical Center, Danville, Pennsylvania. The authors report no conflict of interest. Correspondence: Dong Chen, MD, PhD, Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences, University of Missouri, One Hospital Dr, MA204, DC018.00, Columbia, MO 65212 ([email protected]). 416 I CUTIS® WWW.MDEDGE.COM/CUTIS Copyright Cutis 2018. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted without the prior written permission of the Publisher. DERMATOPATHOLOGY DIAGNOSIS DISCUSSION THE DIAGNOSIS: Erythrasma rythrasma usually involves intertriginous areas surface (Figure 1) compared to dermatophyte hyphae that (eg, axillae, groin, inframammary area). Patients tend to be parallel to the surface.2 E present with well-demarcated, minimally scaly, red- Pitted keratolysis is a superficial bacterial infection brown patches. -

The Phylogeny of Plant and Animal Pathogens in the Ascomycota

Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology (2001) 59, 165±187 doi:10.1006/pmpp.2001.0355, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on MINI-REVIEW The phylogeny of plant and animal pathogens in the Ascomycota MARY L. BERBEE* Department of Botany, University of British Columbia, 6270 University Blvd, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada (Accepted for publication August 2001) What makes a fungus pathogenic? In this review, phylogenetic inference is used to speculate on the evolution of plant and animal pathogens in the fungal Phylum Ascomycota. A phylogeny is presented using 297 18S ribosomal DNA sequences from GenBank and it is shown that most known plant pathogens are concentrated in four classes in the Ascomycota. Animal pathogens are also concentrated, but in two ascomycete classes that contain few, if any, plant pathogens. Rather than appearing as a constant character of a class, the ability to cause disease in plants and animals was gained and lost repeatedly. The genes that code for some traits involved in pathogenicity or virulence have been cloned and characterized, and so the evolutionary relationships of a few of the genes for enzymes and toxins known to play roles in diseases were explored. In general, these genes are too narrowly distributed and too recent in origin to explain the broad patterns of origin of pathogens. Co-evolution could potentially be part of an explanation for phylogenetic patterns of pathogenesis. Robust phylogenies not only of the fungi, but also of host plants and animals are becoming available, allowing for critical analysis of the nature of co-evolutionary warfare. Host animals, particularly human hosts have had little obvious eect on fungal evolution and most cases of fungal disease in humans appear to represent an evolutionary dead end for the fungus. -

Tinea Capitis 2014 L.C

BJD GUIDELINES British Journal of Dermatology British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of tinea capitis 2014 L.C. Fuller,1 R.C. Barton,2 M.F. Mohd Mustapa,3 L.E. Proudfoot,4 S.P. Punjabi5 and E.M. Higgins6 1Department of Dermatology, Chelsea & Westminster Hospital, Fulham Road, London SW10 9NH, U.K. 2Department of Microbiology, Leeds General Infirmary, Leeds LS1 3EX, U.K. 3British Association of Dermatologists, Willan House, 4 Fitzroy Square, London W1T 5HQ, U.K. 4St John’s Institute of Dermatology, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, St Thomas’ Hospital, Westminster Bridge Road, London SE1 7EH, U.K. 5Department of Dermatology, Hammersmith Hospital, 150 Du Cane Road, London W12 0HS, U.K. 6Department of Dermatology, King’s College Hospital, Denmark Hill, London SE5 9RS, U.K. 1.0 Purpose and scope Correspondence Claire Fuller. The overall objective of this guideline is to provide up-to- E-mail: [email protected] date, evidence-based recommendations for the management of tinea capitis. This document aims to update and expand Accepted for publication on the previous guidelines by (i) offering an appraisal of 8 June 2014 all relevant literature since January 1999, focusing on any key developments; (ii) addressing important, practical clini- Funding sources cal questions relating to the primary guideline objective, i.e. None. accurate diagnosis and identification of cases; suitable treat- ment to minimize duration of disease, discomfort and scar- Conflicts of interest ring; and limiting spread among other members of the L.C.F. has received sponsorship to attend conferences from Almirall, Janssen and LEO Pharma (nonspecific); has acted as a consultant for Alliance Pharma (nonspe- community; (iii) providing guideline recommendations and, cific); and has legal representation for L’Oreal U.K.