PLSS) – Part 1 Lorraine Manz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Public Land Survey System for the Cadastral Mapper

THE PUBLIC LAND SURVEY SYSTEM FOR THE CADASTRAL MAPPER FLORIDA ASSOCIATION OF CADASTRAL MAPPERS In conjunction with THE FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE Proudly Presents COURSE 2 THE PUBLIC LAND SURVEY SYSTEM FOR THE CADASTRAL MAPPER Objective: Upon completion of this course the student will: Have an historical understanding of the events leading up to the PLSS. Understand the basic concepts of Section, Township, and Range. Know how to read and locate a legal description from the PLSS. Have an understanding of how boundaries can change due to nature. Be presented with a basic knowledge of GPS, Datums, and Map Projections. Encounter further subdividing of land thru the condominium and platting process. Also, they will: Perform a Case Study where the practical applications of trigonometry and coordinate calculations are utilized to mathematically locate the center of the section. *No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any matter whatsoever without written permission from FACM www.FACM.org Table Of Contents Course Outline DAY ONE MONDAY MORNING - WHAT IS THE PLSS? A. INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW TO THE PLSS……………………………..…………1-2 B. SURVEYING IN COLONIAL AMERICA PRIOR TO THE PLSS………………...……..1-3 C. HISTORY OF THE PUBLIC LAND SURVEY SYSTEM…………………………….….…..1-9 1. EDMUND GUNTER……………………………………………………….………..…..…..……1-10 2. THE LAND ORDINANCE OF 1785…………………………………………..………….……..1-11 3. MAP OF THE SEVEN RANGES…………………………………….……………………………1-15 D. HOW THE PUBLIC LAND SURVEY SYSTEM WORKS………..………………………1-18 1. PLSS DATUM………..…………………………………………………….………………1-18 2. THE TOWNSHIP………..………………………………………………….………………1-18 DAY 1 MORNING REVIEW QUESTIONS……………………………………………..1-20 i Table Of Contents MONDAY AFTERNOON – SECTION TOWNSHIP RANGE A. -

General Land Office Book

FORWARD n 1812, the General Land Office or GLO was established as a federal agency within the Department of the Treasury. The GLO’s primary responsibility was to oversee the survey and sale of lands deemed by the newly formed United States as “public domain” lands. The GLO was eventually transferred to the Department of Interior in 1849 where it would remain for the next ninety-seven years. The GLO is an integral piece in the mosaic of Oregon’s history. In 1843, as the GLO entered its third decade of existence, new sett lers and immigrants had begun arriving in increasing numbers in the Oregon territory. By 1850, Oregon’s European- American population numbered over 13,000 individuals. While the majority resided in the Willamette Valley, miners from California had begun swarming northward to stake and mine gold and silver claims on streams and mountain sides in southwest Oregon. Statehood would not come for another nine years. Clearing, tilling and farming lands in the valleys and foothills and having established a territorial government, the settlers’ presumed that the United States’ federal government would act in their behalf and recognize their preemptive claims. Of paramount importance, the sett lers’ claims rested on the federal government’s abilities to negotiate future treaties with Indian tribes and to obtain cessions of land—the very lands their new homes, barns and fields were now located on. In 1850, Congress passed an “Act to Create the office of the Surveyor-General of the public lands in Oregon, and to provide for the survey and to make donations to settlers of the said public lands.” On May 5, 1851, John B. -

Joseph C. Brown (1784 – 1849)

Joseph C. Brown (1784 – 1849) On March 3, 1825, a bill was signed authorizing a road to be surveyed and marked from Missouri to the Mexican Settlements (Santa Fe). The “Sibley Expedition” (so named for George C. Sibley who emerged as the leader) began its survey near Fort Osage, Missouri on July 17, 1825. Joseph C. Brown was the surveyor on that Sibley Expedition of 1825-26 and he is the one that prepared the maps of the expedition upon his arrival in Taos in 1825. Brown also prepared the maps and "fieldbook" for the official report of the expedition issued in 1827. Brown's maps give us unparalleled documentation of the Santa Fe Trail as it existed in the mid-1820s. His survey of the Santa Fe Trail appears to have an error of less than 1% which is remarkable considering the equipment of the time and the conditions present throughout the survey. During the Sibley Expedition, Brown was present for negotiation of treaties for a right-of-way for and safe passage on the Santa Fe Trail with the Osage at Council Grove and the Kanza near present-day McPherson, KS (that site shown on map inset). Brown was present when Diamond Spring was 'discovered' and probably assisted Sibley in obtaining permission from Mexico to perform the survey in Mexican Territory. Joseph C. Brown served as a U.S. Deputy Surveyor for the General Land Office for over 30 years. In that time he is credited with running thousands of survey miles. His accomplishments include surveying the baseline to establish the beginning point for the first surveys of the Louisiana Purchase Lands, which he began on October 27, 1815, with the survey of the baseline for the Fifth Principal Meridian at the confluence of the Mississippi and St. -

Land Survey Index Help

Land Survey Index Help Table of Contents What is the Public Land Survey System? How are sections marked? Index Grid including Corner and Section Line numbering How do I search for records by township, range, direction and section? How do I search for General Land Office (GLO) Notes? How do I search for subdivisions? What are the column headings on the report? County Fips Codes and Location of Original charts and descriptions Tips for Researching using the Land Survey Index How can I purchase a copy of the search results? FAQ’s What is the Public Land Survey System? The United States Public Land Survey System (USPLSS) in Missouri is an extension of the system adopted by the U.S. Congress in 1785. Between 1815 and 1855, Missouri was surveyed into one mile squares called sections. Thirty-six sections in a block of land measuring six miles on each side is called a township; this created the basis for the transfer of land from the United States Government to private owners and is the basis for all land transfers and ownership in the state today. How are sections marked? The sections were originally marked with wood posts, rocks or mounds of earth. This record of the original survey called the General Land Office (GLO) survey is found in the original field notes and plats. Today, new permanent monuments are placed at the section and ¼ section corners (halfway between section corners). These monuments are aluminum pipes, iron rods, concrete markers or iron pipes with caps stamped to identify the corner. The Missouri Department of Agriculture, county surveyors, and private surveyors assist in setting some of these monuments. -

Standardized PLSS Data Set (PLSS Cadnsdi) Users Reference Materials

Standardized PLSS Data Set (PLSS CadNSDI) Users Reference Materials October 2015 (reviewed October 2016) Handbook for PLSS Standardized Data If you have comments, suggestions, corrections or additions for the material in this document please send them to [email protected] Comments will be accumulated, reviewed and incorporated into the next version of this material. Please see the information listed with the PLSS Work Group on the FGDC Cadastral Subcommittee publication site (http://nationalcad.org/PLSSWorkgroup/PLSSWorkgroup.html) for additional information on the Standardized PLSS CadNSDI Data Sets. Handbook for Standardized PLSS CadNSDI Data Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 Frequently Asked Questions ............................................................................................. 2 General Questions ........................................................................................................... 2 Conflicted Areas - How should a GISer work around conflicted areas? ........................ 6 Survey System and Parcel Feature Classes - The feature classes "Survey System" and “Parcel” do not have any data in them, why is this? ...................................................... 6 PLSS Township ................................................................................................................ 7 Metadata at a Glance ..................................................................................................... -

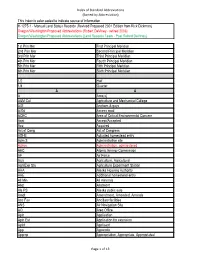

Index of Standard Abbreviations (Sorted by Abbreviation) This Index Is Color Coded to Indicate Source of Information

Index of Standard Abbreviations (Sorted by Abbreviation) This Index is color coded to indicate source of information. H-1275-1 - Manual Land Status Records (Revised Proposed 2001 Edition from Rick Dickman) Oregon/Washington Proposed Abbreviations (Robert DeViney - retired 2006) Oregon/Washington Proposed Abbreviations (Land Records Team - Post Robert DeViney) 1st Prin Mer First Principal Meridian 2nd Prin Mer Second Principal Meridian 3rd Prin Mer Third Principal Meridian 4th Prin Mer Fourth Principal Meridian 5th Prin Mer Fifth Principal Meridian 6th Prin Mer Sixth Principal Meridian 1/2 Half 1/4 Quarter A A A Acre(s) A&M Col Agriculture and Mechanical College A/G Anchors & guys A/Rd Access road ACEC Area of Critical Environmental Concern Acpt Accept/Accepted Acq Acquired Act of Cong Act of Congress ADHE Adjusted homestead entry Adm S Administrative site Admin Administration, administered AEC Atomic Energy Commission AF Air Force Agri Agriculture, Agricultural Agri Exp Sta Agriculture Experiment Station AHA Alaska Housing Authority AHE Additional homestead entry All Min All minerals Allot Allotment Als PS Alaska public sale Amdt Amendment, Amended, Amends Anc Fas Ancillary facilities ANS Air Navigation Site AO Area Office Apln Application Apln Ext Application for extension Aplnt Applicant App Appendix Approp Appropriation, Appropriate, Appropriated Page 1 of 13 Index of Standard Abbreviations (Sorted by Abbreviation) Appvd Approved Area Adm O Area Administrator Order(s) Arpt Airport ARRCS Alaska Rural Rehabilitation Corp. sale Asgn Assignment -

PTAX 1-M, Introduction to Mapping for Assessors

1-M, Introduction to Mapping for Assessors # 001-805 68 PTAX 1-M Rev 02/2021 1 Printed by the authority of the State of Illinois. web only, one copy 2 Table of Contents Glossary ............................................................................................................ Page 5 Where to Get Assistance ................................................................................... Page 10 Unit 1: Basic Types and Uses of Maps ............................................................. Page 13 Unit 2: Measurements and Math for Mapping .................................................. Page 33 Unit 3: The US Rectangular Land Survey ........................................................ Page 49 Unit 4: Legal Descriptions ................................................................................ Page 63 Blank Practice Pages ...................................................................................... Page 94 Unit 5: Metes and Bounds Legal Descriptions .................................................. Page 97 Unit 6: Principles for Assigning Property Index Numbers ................................. Page 131 Unit 7: GIS and Mapping .................................................................................. Page 151 Exam Preparation.............................................................................................. Page 160 Answer Key ....................................................................................................... Page 161 3 4 Glossary Acre – A unit of land area in England -

A Line Runs Through It PLSC Supports New 40Th Parallel Exhibit

Photo inset above shows the brass monu- An eye-catching red line bisects two massive ment set in the exhibit’s stone bench. It is halves of a cut stone, marking the baseline set the first position posted to the beta NGS by Todd & Withrow in 1859. It runs next to a bus OPUS-DB database in Colorado. stop on Baseline Road in Boulder, Colorado. Displayed with permission • The American Surveyor • March • Copyright 2009 Cheves Media • www.Amerisurv.com A LINE RUNS THROUGH It PLSC Supports New 40th Parallel Exhibit he northern Front Range of what is now Colorado was a pristine wilderness well into the 1850s, trampled only by a small number of trappers and explorers, and by the light footprints of native peoples who had inhabited the area for over a millennium. These halcyon days changed quickly with the discovery of gold in nearby Golden, resulting in thousands of settlers moving onto public domain lands that had not yet been surveyed. In 1859, the land at the mouth of Boulder Canyon was officially established as the Boulder City Town Company. It was located north of the 40th parallel in the Nebraska Territory; the land to the south of the 40th parallel at this time was in the Kansas Territory. Colorado statehood was to come 17 years later. Extending the 40th Parallel Westward The General Land Office was under pressure to extend the Baseline to the west from the 6th Principal Meridian. On June 10, 1859, U. S. Deputy Surveyors Jarret Todd and James Withrow were awarded the contract to extend the baseline to the summit of the Rockies, starting 204 miles west of the Missouri River, and making their way across the plains until arriving in Boulder City on August 31 of that year. -

The Ohio Surveys

Report on Ohio Survey Investigation -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- A Report on the Investigation of the FGDC Cadastral Data Content Standard and its Applicability in Support of the Ohio Survey Systems Nancy von Meyer Fairview Industries, Inc For The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) National Integrated Land System (NILS) Project Office January 2005 i Report on Ohio Survey Investigation -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Preface Ohio was the testing and proving grounds of the Public Land Survey System (PLSS). As a result Ohio contains many varied land descriptions and survey systems. Further complicating the Ohio land description scene are large federal tracts reserved for military use and lands held by other states prior to Ohio statehood. This document is not a history of the land system development for Ohio. The history of Ohio surveys can be found in other materials including the following: Downs, Randolf C., 1927, Evolution of Ohio County Boundaries”, Ohio Archeological and Historical Publications Number XXXVI, Columbus, Ohio. Reprinted in 1970. Gates, Paul W., 1968. “History of Public Land Law Development”, Public Land Law Review Commission, Washington DC. Knepper, George, 2002, “The Official Ohio Lands Book” Auditor of State, Columbus Ohio. http://www.auditor.state.oh.us/StudentResources/OhioLands/ohio_lands.pdf Last Accessed November 2, 2004 Petro, Jim, 1997, “Ohio Lands A Short History”, Auditor of State, Columbus Ohio. Sherman, C.E., 1925, “Original Ohio Land Subdivisions” Volume III of the Final Report to the Ohio Cooperative Topographic Survey. Reprinted in 1991. White, Albert C., “A History of the Public Land Survey System”, US Government Printing Office, Stock Number 024-011-00150-6, Washington D.C. -

Specifications for Descriptions of Land: for Use in Land Orders, Executive Orders, Proclamations, Federal Register Documents, and Land Description Databases

United States Department of the Interior • Bureau of Land Management • Cadastral Survey Specifications for Descriptions of Land: For Use in Land Orders, Executive Orders, Proclamations, Federal Register Documents, and Land Description Databases Revised 2017 Specifications for Descriptions of Land: For Use in Land Orders, Executive Orders, Proclamations, Federal Register Documents, and Land Description Databases Produced in coordination with the Office of Management and Budget, United States Federal Geographic Data Committee, Cadastral Subcommittee Washington, DC: 2015; Revised 2017 U.S. Department of the Interior Suggested citation for general reference: U.S. Department of the Interior. 2017. Specifications for Descriptions of Land: For Use in Land Orders, Executive Orders, Proclamations, Federal Register Documents, and Land Description Databases. Bureau of Land Management. Washington, DC. Suggested citation for technical reference: Specifications for Descriptions of Land (2017) Find these Specifications and other information at www.blm.gov. Printed copies are available from: Printed Materials Distribution Services Fax: 303-236-0845 Email: [email protected] Stock Number: P-474 BLM/WO/GI-17/007+1813 U.S. Department of the Interior The mission of the Department of the Interior (Department) is to protect and provide access to our Nation’s natural and cultural heritage and honor our trust responsibilities to Indian tribes and our commitments to island communities. The Department works to assure the wisest choices are made in managing all of the Nation’s resources so each will make its full contribution to a better United States—now and in the future. The Department manages about 500 million acres, or one-fifth, of the land in the United States. -

Principal Meridian the Initial Point Of

The Initial Point of the Principal Meridian ovember 10, 2015 is an important date to nearly every American who owns land in the states of Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, North Dakota and in parts of Minnesota and South Dakota. Every surveyor in those states should stop for a moment, and with head bowed, remember every GLO Deputy Surveyor who surveyed on the U.S. Public Land Survey System (USPLSS). Why November 10, 2015? Because that will be 200 years to the day—the Bicentennial—of the establishment of the Initial Point for the 5th Principal Meridian. That initial point is “zero, zero,” the point to which practically all titles to the lands listed in the states above are referenced. More land in the United States is referenced to this point, in a swamp in eastern Arkansas, than any other Initial Point. From that point the township and range numbering systems begins for those states. It ends at the northwest corner of North Dakota, in Township 164 North, Range 103 West. See Figure 1. 1785–1815 The genesis of our USPLSS can be traced back to the Land Ordinance of May 20, 1785. The system’s first experiment was in the Seven Ranges of southeastern Ohio, then spread westerly being modified and improved into the Northwest Territories and beyond. Under the system, each large segment of land requires a North-South Principal Meridian and an East-West Base Line, the intersection of these lines being the Initial Point. These Initial Points are the “zero, zero” for the USPLSS, from which township and range numbering begins. -

The Public Land Surveys Spread Across Minnesota

THE FIRST TOWNSHIP EXTERIORS IN MINNESOTA Rod Squires, University of Minnesota Introduction The rectangular public land survey net was laid out on the land surface in two steps. First, a deputy was awarded a contract to run the exterior lines of townships and set the appropriate corner monuments on them. Then a second deputy was awarded a contract to subdivide those townships. Both steps were described in the General Instructions but the work of the two was obviously quite different. Moreover, the deputy creating the township exterior in an area was working without any knowledge of the area and with only the controls or existing points of reference that had been previously made in a different area, and to which he was to connect. As a way of introducing the topic I explore the township exterior surveys made in 1847 by James M. Marsh under the general instructions of 1846.1 (Figure 1) There are two important reasons for looking at township exteriors. First, any line that the modern land surveyor needs to retrace or resurvey may be an exterior line or a subdivision line. Similarly, any corner that needs to be located or reestablished may lie on a township exterior. 2 Thus, the modern land surveyor must be aware of how township exteriors were run and monumented. Secondly, the survey records, such as the field notes and the township plats used by surveyors to reconstruct the lines and reestablish the corners are a blend of the records relating to both exteriors and subdivisions. In fact, they contain information relating to a minimum of two different contracts awarded to two different deputies at two different times.