Evaluating Social Transparency in Global Apparel Supply Chains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effects of Globalization on the Fashion Industry– Maísa Benatti

ACKNOLEDGMENTS Thank you my dear parents for raising me in a way that I could travel the world and have experienced different cultures. My main motivation for this dissertation was my curiosity to understand personal and professional connections throughout the world and this curiosity was awakened because of your emotional and financial incentives on letting me live away from home since I was very young. Mae and Ingo, thank you for not measuring efforts for having me in Portugal. I know how hard it was but you´d never said no to anything I needed here. Having you both in my life makes everything so much easier. I love you more than I can ever explain. Pai, your time here in Portugal with me was very important for this masters, thank you so much for showing me that life is not a bed of roses and that I must put a lot of effort on the things to make them happen. I could sew my last collection because of you, your patience and your words saying “if it was easy, it wouldn´t be worth it”. Thank you to my family here in Portugal, Dona Teresinha, Sr. Eurico, Erica, Willian, Felipe, Daniel, Zuleica, Emanuel, Vitória and Artur, for understanding my absences in family gatherings because of the thesis and for always giving me support on anything I need. Dona Teresinha and Sr. Eurico, thank you a million times for helping me so much during this (not easy) year of my life. Thank you for receiving me at your house as if I were your child. -

Trend-Sandwich

Trend-sandwich Exploring new ways of joining inspiration, such as different kinds of trends, through processes of morphing and melding different trendy garments and materials, for new methods, garment types, materials and expressions. Daniel Bendzovski MA Fashion Design Thesis 2015 2015.6.01 CONTENT 0: Abstract 1: Keywords 2: Result 3: Background 4: Background to current design program and degree work 5: Design program 6: Fashion as commodity and trend 7: General trend theories 8: Trend forecasting methods 9: Commercial fashion and its inspiration 10: Joining of different inspirations 11: Computer softwares, 2D and 3D morphing 12: Aim 13: Method, general review 14: Development 15: Morphing silhouettes in adobe flash, general review 16: Development part one 17: Development part two 18: Methodological turnaround, material experiments 19: From material experiment to sketched line up 20: From sketched line up to physical material development 21: Development of physical garment shape in relation to body 22: Improvisational making of garment, meeting of material and shape in relation to body 23: Result 24: Thoughts on research 25: Context 26: Discussion 27: References 0: ABSTRACT The aim of this work is to explore the joining of inspiration, such as different garments and materials, in relation to commonly used methods in the fashion industry when it comes to joining of different trends and references such as clashing and collaging. The work proposes a new method and framework for join- ing inspiration which generates different results depending on what kind of inspiration that is put in to it. A garment can roughly be broken down to a silhouette and shape, materials and details. -

Stilettodaily03

Collections prêt-à-porter printemps-été 2016, Paris | Vendredi 2 octobre 2015 Français | English Stilettodaily03 dior dior #FallWinter2015 # Sebastian Mader #Stylist Vanessa Chow #itDior #Stiletto Éditorial n talon comme un glaçon couleur Haribo, Plexi rafraîchissant pour arpenter la heel like a candy-colored ice-cube and refreshing Plexiglas to roam the city and melt ville et fondre de bonheur en admirant les œuvres de Madame Vigée-Lebrun au while admiring the works of Madame Vigée-Lebrun at the Louvre, or of “Fragonard Louvre, de « Fragonard amoureux » au musée du Luxembourg. Des souliers aux in Love” at the musée du Luxembourg. From shoes to purses, addiction is leaning sacs, l’addiction prend des nuances très bonbon, on a envie de croquer dans le cuir more and more toward candy colors: leather as enticing as a cupcake of Sébastien Ucomme dans un mussipontain de Sébastien Gaudard, les pochettes rose barbe-à-papa et les Gaudard,A cotton-candy pink purses and soft hold-all pouches that we could stu full when young besaces aussi douces que les objets transitionnels de l’enfance, nous plongent dans un meilleur children. Here we go sliding into the best of hashtag worlds with virtual hearts and suns. What des mondes hashtaggé de cœurs et de soleils virtuels. Ce que l’hiver promettait en régressions winter promised in terms of teenage regression, the summer of will be magnifying still further adulescentes, l’été le magni e encore, dans une pléiade d’échappées belles, aux couleurs de with an array of beautiful adventures in the colors of ne pastries and sweet journeys. -

P38-40 Layout 1

lifestyle WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2016 FASHION What to look out for at Paris fashion week aris fashion week started yesterday with dizzying ture house of them all. The 45-year-old takes over from Alber changes at the top of some of the most famous brands. Elbaz, who was fired in October 2015 after 14 years at the head PSaint Laurent, Dior and Lanvin all have new artistic direc- of the label, in a move that caused dismay at the time. tors who will be putting on their first shows in their new roles. The label’s redoubtable Taiwanese owner businesswoman With more than 90 runway shows and dozens more presen- Shaw-Lan Wang has now turned to Jarrar, and her pure, ele- tations behind closed doors over nine days, the spring-sum- gant lines are likely to mark Lanvin’s show on Wednesday. mer ready to wear collections promise to be the most scruti- Jarrar, whose parents came from Morocco, worked her way up nized for some time. Here is our guide to the shows to watch through Balenciaga and Christian Lacroix before launching her out for: own label in 2010. Saint Laurent after Slimane Dior’s Italian job How will Anthony Vaccarello face up to the massive chal- But perhaps the week’s biggest moment will be Italian lenge of filling Hedi Slimane’s Chelsea boots at Saint Laurent is designer Maria Grazia Chiuri’s debut show on Friday at Dior as the question on many fashionistas’ lips. Slimane, the man cred- the first woman ever to lead the house. -

Haute Couture

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 17, 2015 TORONTO STAR TIFF 2015 STYLE SPECIAL INSIDE: Our editors on the top 10 best dressed celebs, plus gorgeous red carpet beauty looks, the festival’s hottest movies and show-stopping fragrances inspired by the silver screen THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 17, 2015 TORONTO STAR BEST DRESSED LIST Fashion to die for and knockout beauty looks: Our editors select the most stunning TIFF red carpet style page 4 Jessica Chastain in Givenchy at TIFF 2015. Photo: Getty Images. FRAGRANCE TRUE STORY “Falling in love happened. In Toronto. At the Rogers Centre. EXPERT ADVICE Under several banners of BACKSTAGE REPORT MICHAEL Blue Jays history. This is where HAUTE KORS I won the hearts of One Direction.” COUTURE page 6 The designer talks Super-cool beauty jet-set glamour lessons from the pros page 5 page 8 © CHANEL 2015 STAY CONNECTED THEKIT.CA @THEKIT @THEKITCA THEKITCA THEKIT THE KIT MAGAZINE THEKIT.CA / 3 TIFF 2015 BEST SNAPS MOST WANTED INSTA ACCESS Didn’t make the TIFF VIP list? Look no further; the best views Object are right here. —Carly Ostroff of desire As with everything Miuccia Prada touches, the first Miu Miu fragrance feels both fondly familiar and entirely new. The opaque turquoise glass bottle borrows its curves from the matelassé quilted leather of the brand’s street-style-catnip handbags, their grown-up luxury slightly subverted by cartoonishly large closures. The clear red disk moonlighting as a cap calls to mind Paco Rabanne’s swinging ’60s @chastainiac My glam squad minis made entirely of plastic circles. Together, @renatocampora @kristofer- they’re delicious eye candy matched only by the black buckle looking hot in Toronto and white kitten that features prominently in the ad #TheMartian #pressdays campaign. -

MÉDÉE POÈME ENRAGÉ JEAN-RENÉ LEMOINE PROGRAMMATION HORS LES MURS DE LA MC93 Théâtre Du Soleil FESTIVAL LE STANDARD IDÉAL - 10E ÉDITION

LES THÉÂTRES PARTENAIRES MÉDÉE POÈME ENRAGÉ JEAN-RENÉ LEMOINE PROGRAMMATION HORS LES MURS DE LA MC93 Théâtre du Soleil FESTIVAL LE STANDARD IDÉAL - 10E ÉDITION WWW.MC93.COM Revoici Jean-René Lemoine et Médée, poème enragé, un opéra pour un récitant accompagné d’un musicien. Cette réécriture du mythe, en trois mouvements, s’articule autour de la pulsion. Tout est vécu comme un rêve. Il s’agit de faire vivre et d’entrelacer les cultures, le passé et présent, pour essayer de créer un chant, une mythologie contemporaine avec ses pulsations et son lyrisme. Médée concentre en elle toutes les héroïnes tragiques. Elle est celle qui agit, qui décide, qui transgresse. Elle refuse la fonction de l’attente dévolue la plupart du temps aux femmes dans la mythologie, elle s’impose comme « héros », faisant ainsi de Jason une figure féminine. Le mythe permet photo Alain Richard de nommer l’innommable, l’inacceptable, il peut raconter l’horreur, dire l’interdit car il contient dans sa puissance poétique sa propre rédemption. Il s’agit donc à travers la fable, de tenter de raconter l’intime, l’indicible du lien amoureux, du lien filial, l’insatiable et tragique quête de l’amour, la solitude face au monde et à la société. THÉÂTRE GÉRARD PHILIPE, CDN DE SAINT-DENIS 27 MARS - 3 AVRIL 2015 À 20H30, À 16H LE DIMANCHE RELÂCHES LES 31, 1ER ET 2 AVRIL RÉSERVATION MC93 01 41 60 72 72 RÉSERVATION THÉÂTRE GÉRARD PHILIPE WWW.MC93.COM 01 48 13 70 00 WWW.THEATREGERARDPHILIPE.COM Tarifs : de 22 à 6€ CONTACT PRESSE MC93 FESTIVAL LE STANDARD IDÉAL DRC / Dominique Racle -

Gowns by the Numbers

Gowns By the Numbers Haute Couture Spring/Summer 2020 Trend Report The Current State of Fashion Fashion, along with every other industry, has been completely shaken up by the COVID-19 pandemic. As the world faces unprecedented challenges that are forcing many to rethink the systems currently in place, the fate of fashion remains to be seen. In the meantime, the industry is doing what it can to comply with the new rules and regulations and aid in the fight against the virus. Source: Women’s Wear Daily In an effort to stop the spread... ● Retailers, at every level, closed their stores for an indefinite period of time ● Fabric mills and workshops around the globe halted production. ● American designers from Christian Siriano to Brandon Maxwell started producing face masks. ● The French luxury group LVMH, which owns Givenchy and Dior among others, converted its makeup factories to produce hand sanitizer. More recently ● The Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode, France’s governing body, announced on March 27 that the Haute Couture collections for Fall/Winter 2020 will not go on as planned. Source: Women’s Wear Daily About Haute Couture ● Haute Couture translates to “high dressmaking” and is protected by law in France ● The Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode is the institution which sets in place and upholds the rules: ○ Designers and houses must be maintain an atelier (workshop) in Paris ○ The atelier must employ at least fifteen full-time staff and twenty full-time dressmaking experts. ○ They must provide made-to-order clothing that is custom-fitted and sewn by hand for their clients. -

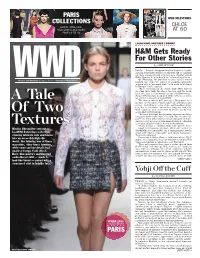

A Tale of Two Textures

PARIS WWD MILESTONES COLLECTIONS LANVIN, NINA RICCI, CHLOE RICK OWENS AND MORE. AT 60 PAGES 6 TO 10. LAUNCHING ANOTHER FORMAT H&M Gets Ready For Other Stories By ALEX WYNNE PARIS — Despite disappointing third-quarter results, fashion behemoth Hennes & Mauritz AB is ramping up store expansion and writing a new chapter with & Other Stories, its new brand set to launch next year. FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2012 ■ $3.00 ■ WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY On Thursday, the Swedish retailer said it would launch the concept, aimed at fashion-conscious WWD women with a “personal look,” with eight to 10 stores in Europe’s style capitals. “We’re focusing on the whole look. [For] women creating their look, the shoes, the bag and the neck- lace are just as important as the ready-to-wear,” Samuel Fernström, head of & Other Stories, said in an exclusive interview with WWD. A Ta le The stores, which will average 7,500 square feet in size, are to offer a wide range of categories and prices, including a large shoe and handbag offer, jewelry, accessories, cosmetics, lingerie and rtw, with “quality” and “attention to detail” being key, Of Two according to Fernström. “We have different design teams focusing on differ- ent parts of the collection,” he said. The creative de- partment for & Other Stories is based largely in Paris, and is led by head of design Anna Teurnell, although a second, smaller team is based in Stockholm. Tex t u res “Paris brings a tomboy look with poetic hints Nicolas Ghesquière sent out a — tough yet feminine designs, while our atelier in Stockholm is responsible for a minimalistic touch, beautiful Balenciaga collection, some raw edges, sensuality and sharp tailoring,” steering intricate cuts and fabrics Teurnell explained. -

Semaine De La Haute Couture – Défilés Printemps-Eté 2020 From

Semaine de la Haute Couture – Défilés Printemps-Eté 2020 From January 20th to January 23rd The week dedicated to Haute Couture starts this Monday. 34 shows will run until January 23rd. BOUCHRA JARRAR is back on the calendar as Haute Couture member, bringing to 16 the number of Haute Couture labelled houses this year : ADELINE ANDRÉ, ALEXANDRE VAUTHIER, ALEXIS MABILLE, BOUCHRA JARRAR, CHANEL, CHRISTIAN DIOR, FRANCK SORBIER, GIAMBATTISTA VALLI, GIVENCHY, JEAN-PAUL GAULTIER, JULIEN FOURNIÉ, MAISON MARGIELA, MAISON RABIH KAYROUZ, MAURIZIO GALANTE, SCHIAPARELLI, STÉPHANE ROLLAND. Correspondent members presenting a collection this season are: GIORGIO ARMANI PRIVÉ, ELIE SAAB, VICTOR & ROLF, VALENTINO. 16 houses are invited members: AGANOVICH, AELIS, ANTONIO GRIMALDI, AZZARO COUTURE, GEORGES HOBEIKA, GUO PEI, IMANE AYISSI, IRIS VAN HERPEN, JULIE DE LIBRAN, RALPH & RUSSO, RAHUL MISHRA, RVDK/RONALD VAN DER KEMP, ULYANA SERGEENKO, XUAN, YUIMA NAKAZATO, ZUHAIR MURAD. Among the High Jewelry houses showcased on the Official Schedule, 4 will be presenting a collection this season: CHANEL JOAILLERIE, CHOPARD, DIOR JOAILLERIE, LOUIS VUITTON JOAILLERIE. Marie Schneier Responsable Communication 100-102, rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré – 75008 PARIS Portable: +33 (0)6 60 87 71 78 / [email protected] The events of the week - The « Dîner de la Mode – Sidaction » will complete the week and will be held at the Pavillon Cambon Capucines. The duo Amandine Chaignot, Pouliche restaurant’s cheffe and Christelle Brua, Elysee Palace’s pastry cheffe and 2018 world best restaurant pastry cheffe, will sign the menu of this special evening. - The exhibit Alaïa Collector: « Alaïa and Balenciaga, Sculptors of shape » held at the Fondation, 18, rue de la Verrerie 75004, from January 19th to June 28th. -

A Golden Opportunity: Supporting Up-And-Coming U.S. Luxury Designers Through Design Legislation, 42 Brook

Brooklyn Journal of International Law Volume 42 | Issue 1 Article 7 2016 A Golden Opportunity: Supporting Up-and- Coming U.S. Luxury Designers Through Design Legislation Shieva Salehnia Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, European Law Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Shieva Salehnia, A Golden Opportunity: Supporting Up-and-Coming U.S. Luxury Designers Through Design Legislation, 42 Brook. J. Int'l L. 367 (2016). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil/vol42/iss1/7 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. A GOLDEN OPPORTUNITY: SUPPORTING UP-AND-COMING U.S. LUXURY DESIGNERS THROUGH DESIGN LEGISLATION INTRODUCTION he luxury industry has played an important part in the Tcultural evolution of contemporary societies, growing rap- idly in sales and global reach over the last two decades.1 Sales of personal luxury goods have tripled in the past twenty years, bal- looning to €253 billion in worldwide retail sales value in 2015.2 Clothing in particular has been an imperative element of the personal luxury goods industry, accounting for 24 percent of all global luxury market sales.3 Events celebrating the more crea- tive and often decadent aspects of fashion like “Fashion Week” now occur on most continents.4 The United States and the emerging market of China5 are cur- rently the biggest players in the personal luxury goods market. -

La Mode Aime Paris »

Dossier de presse – 3 mars 2015 – Campagne « La Mode aime Paris » 1 SOMMAIRE Chiffres clés : la Semaine de la mode à Paris collections automne-hiver 2015/2016 ............ 3 Deux expositions mettent la mode à l’honneur ………………………………………………..… 4 L’Ecole Duperré de Paris : un fleuron national de la formation en design de mode ….…...… 6 Bouchra Jarrar, portrait d’une ancienne élève de l’Ecole Duperré, aujourd’hui créatrice de renommée internationale …………………………………………………………………………… 7 La mode innove à Paris : l’exemple de la start-up L’Exception ………………………………... 8 2 « Durant la Semaine de la mode, les grands couturiers comme les jeunes talents se donnent rendez-vous à Paris. Vibrant au rythme incessant des défilés et des présentations, la capitale révèle l’incomparable vitalité de ses créateurs, qui bénéficient d’une vitrine unique sur leurs métiers et leurs savoir- faire. Je souhaite que Paris offre à tous les amoureux de la mode une Semaine exceptionnelle. » Anne Hidalgo, Maire de Paris CHIFFRES CLES : LA SEMAINE DE LA MODE A PARIS COLLECTIONS AUTOMNE-HIVER 2015/2016 • Ouverture le mardi 3 mars. • 92 défilés prévus dans le calendrier officiel, auxquels s’ajoutent une cinquantaine de présentations "off" et les showrooms de créateurs. • 25 nationalités. • 1.400 journalistes et photographes du monde entier représentant 434 supports médiatiques émanant d’une cinquantaine de pays. • Les Maisons membres de la Fédération de la Couture, du prêt-à-porter des couturiers et des créateurs de mode pèsent près de 17 milliards d’euros. • Ces marques sont présentes dans 1.500 boutiques en propre et 5.000 distributeurs multimarques. • Ces Maisons membres font travailler 17 000 salariés en France. -

London Men's Fashion Week

MEN’S FASHION WEEK Spring 2017 A.P.C. Vouge.com Given his track record of enlivening A.P.C. presentations with culturally and politically charged spiel, Jean Touitou was bound to have an opinion on Brexit. Simply put, he expressed no surprise. “We are entering a new loop in history, which is totally reactionary,” he said, hypothesizing that the U.S., France, and Italy might face similar fates. Was he concerned? “Oh yes, but I’ve been terrified from a long time ago, back when I was this age,” he replied, pointing to his T-shirt printed with a photo of a foxy Jean Touitou, aged 15. The two Touitous—then and now—provided an entry point into this collection, which will arrive in stores just as the brand enters into its 30th year. Its founder, meanwhile, recently reached the legal age of retirement in France. Leaving aside sentimentality, the milestones marked an opportunity to pay respect to the brand’s workwear DNA, which, Touitou rightly noted, has gotten better with age (more resources, more research). For example: Dungarees and a ribbed pullover were uniquely bleached and overprinted, respectively, to achieve an authentically lived-in look before ever being worn. Roomy jeans, ordinarily a tough sell, were justifiable when paired with a deep indigo, contrast-stitched postman’s jacket. Amid the continued trend toward graphic streetwear, a crisp mac over a shirt patterned in stylized propellers (care of graphic artist Pierre Marie) and a cable-knit tucked into high-waist denim made a compelling case against cool. The streamlined designs from Louis Wong, a member of the design team whose label, Louis W., exists under the A.P.C.