Nonmarketable Assets Version of the CAPM: the Case of the Russian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supply Chain Business Model GRI 106–2, GRI 102–7, GRI 102–9

Annual Report of PJSC Inter RAO for 2020 Strategic report Sustainable Development Report Corporate Governance Report Appendix 024/025 Supply chain business model GRI 106–2, GRI 102–7, GRI 102–9 Supplier Inter RAO Group Consumers st ELECTRIC POWER Installed capacity of 1st pricing zone of WECM nd 1 pricing zone of WECM Europe and European non-pricing zones GAS SUPPLY Installed capacity of 2 GRID COMPANIES OF RUSSIA 25 GENERATION IN RF and European non-pricing zone 19,933 MW, 5,072 Gcal/h pricing zone of WECM ROSNEFT GROUP 1,855 MW, 554 Gcal/h Gas-fired generation of electricity and heat Coal-fired generation of electricity and heat GAZPROM GROUP bln m3 63,557 mln kWh, 3,569,000 Gcal 3,010 mln kWh, 411,000 Gcal 21,788 Gas-fired Coal-fired power Coal-fired JSC BPGC MW power plants plants power plants 18,541 MW, 1,392 MW, 1,855 MW, COAL SUPPLY 1 5,626 4,580 Gcal/h 492 Gcal/h 554 Gcal/h 10.5 Gcal/h 2nd pricing zone of WECM Siberia JSC RAZREZ KHARANORSKY MUNICIPAL HEATING NETWORKS LLC LOGOTRANSENERGO mln t LLC RUSEXPORTUGOL st nd Gas-fired generation of electricity and heat Coal-fired generation of electricity and heat LLC ARMZ SERVICE JSC RZD THERMAL POWER Installed capacity of 1 pricing zone of WECM Installed capacity of 2 GENERATION IN RF 4,260 MW, 12,216 Gcal/h pricing zone of WECM 2,959 mln kWh, 9,830,000 Gcal 11,874 mln kWh, 5,634,000 Gcal 2,051 MW, 7,192 Gcal/h FUEL OIL SUPPLY 75,000 PJSC ROSNEFT OC t LLC REGIONTOPRESURS 1st pricing zone of WECM Europe PJSC GAZPROM NEFT ELECTRICITY AND HEAT CONSUMERS IN RUSSIA Gas-fired generation of -

Uniper and Fortum

FORTUM – For a cleaner world Investor / Analyst material April 2018 Disclaimer This presentation does not constitute an invitation to underwrite, subscribe for, or otherwise acquire or dispose of any Fortum shares. Past performance is no guide to future performance, and persons needing advice should consult an independent financial adviser. Any references to the future represent the management’s current best understanding. However the final outcome may differ from them. 2 Content Fortum today 4 – 18 European and Nordic power markets 19 – 26 Fortum’s nuclear fleet 27 – 30 Russia 31 – 33 Thermal capacity in Russia 33 Historical achieved prices 34 Interim Report Q1 2018 35 – 55 Uniper investment 56 – 59 IR contacts 60 3 Appr. 130,000 shareholders • Power and heat company in the Nordic Finnish households countries, Russia, Poland and the Baltics 10.3% Financial and • Listed at the Helsinki Stock Exchange insurance institutions 1.4% since 1998 Other Finnish • Among the most traded shares on investors the Nasdaq Helsinki stock exchange 7.5% Finnish • Market cap ~16 billion euros State 50.8% Foreign investors 30.0% 28 February 2018 4 Capital returns: 2017 EUR 1.10 per share ~ EUR 1 billion Fortum’s dividend policy is based on 5 year dividend per share (EUR) history the following preconditions: • The dividend policy ensures that shareholders receive a fair remuneration for their entrusted capital, supported 1,4 1.3 by the company’s long-term strategy that aims at increasing earnings per share and thereby the dividend. 1,2 1.1 0.2 1.1 1.1 1.1 • When proposing the dividend, the Board of Directors 1,0 1.1 looks at a range of factors, including the macro 0,8 environment, balance sheet strength as well as future investment plans. -

QUARTERLY REPORT Public Joint-Stock Company

QUARTERLY REPORT Public Joint-Stock Company Federal Hydrogeneration Company RusHydro Code of the Issuer: 55038-E for Q4 2015 Address of the Issuer: 43 Dubrovinskogo St., bldg. 1, Krasnoyarsk, Krasnoyarsk Krai, 660017. The information contained herein is subject to disclosure pursuant to the securities legislation of the Russian Federation Chairman of the Management Board ― General Director ___________________ N.G. Shulginov Date: 15.04.2016 signature _________________ D.V. Finkel Chief Accountant signature Date: 15.04.2016 Contact person: Roman Yurievich Sorokin, Head of Methodology of Corporate Governance and Property Management Department Tel.: +7 800 333 8000 Fax: +7(495) 225-3737 E-mail: [email protected] The address of the Internet site (sites) where the information contained herein is to be disclosed: www.rushydro.ru, http://www.e-disclosure.ru/portal/company.aspx?id=8580 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................................... 2 I. Information on Bank Accounts, Auditor (Audit Organization), Appraiser, and Financial Advisor of the Issuer, as well as on Persons who Have Signed the Quarterly Report ................................................................................ 6 1.1. Information on the Issuer's Bank Accounts .................................................................................................. 6 1.2. Information on the Issuer's Auditor (Audit Organization) .......................................................................... -

Download PDF Competitive Cost-Advantage And

INVESTMENT CASE COMPETITIVE COST-ADVANTAGE AND KNOWHOW MANAGEMENT SUEK is a leader in the resilient energy, logistics and premium coal markets. REINFORCING OUR LEADERSHIP POSITION No. 6 No. 3 No. 2 No. 4 No. 4 electricity heat producer bulk port gondola railcar coal exporter producer in Russia operator operator globally in Russia in Russia in Russia (TWh) (MGcal) (Mt) Gondola railcars (Mt) managed (ths units) Rosenergoatom Gazprom Energoholding Kuzbassrazrezugol Federal Freight Company Glencore 216 108.3 54 112 78.4 Rushydro T plus SUEK First Freight Company BHP Billiton 131 91.8 50 72 60.4 Gazprom Energoholding SUEK NMTP Modum Trans Bumi Resources 127 43.7 23 68 55.2 Inter RAO Inter RAO UCL Port SUEK SUEK 106 37.3 18 48 53.8 En+ Group RusHydro Mechel Globaltrans Anglo American 82 29.4 14 47 49.8 SUEK En+ Group NefteTransService Adaro 64 26.9 37 40.8 T Plus Kvadra Novotrans Yancoal 55 21.2 25 37.9 UniPro Tatenergo Ugol-Trans Sinar Mas 42 10.5 23 36.8 Source: Companies' public data. MAINTAINING A LOW-COST POSITION THROUGH INTEGRATION Our coal producing assets are positioned at the lower end of the global cost curve due ( $/t, FOB) to economies of scale, highly efficient production and RUB denominated cost base. 100 Quartile 1 Quartile 2 Quartile 3 Quartile 4 FOB NEWC = 75 60.5 $/t (2020 average) 50 API2 = 50.3 $/t (2020 average) 25 SUEK 0 Other eporters 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 (Mt) Sources: Wood Mackenzie, SUEK estimates. -

2017 Annual Report of PJSC Inter RAO / Report on Sustainable Development and Environmental Responsibility

INFORMATION TRANSLATION Draft 2017 Annual Report of PJSC Inter RAO / Report on Sustainable Development and Environmental Responsibility Chairman of the Management Board Boris Kovalchuk Chief Accountant Alla Vainilavichute Contents 1. Strategic Report ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 8 1.1. At a Glance .................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 1.2. About the Report ........................................................................................................................................................................ 11 Differences from the Development Process of the 2016 Report ............................................................................................................ 11 Scope of Information ............................................................................................................................................................................. 11 Responsibility for the Report Preparation .............................................................................................................................................. 11 Statement on Liability Limitations ......................................................................................................................................................... -

1 Press Conference Gazprom's Power Generation Strategy May 16, 2018

Press Conference Gazprom’s Power Generation Strategy May 16, 2018 MODERATOR: Good afternoon. We continue the series of Press Conferences in the lead-up to the annual General Shareholders Meeting of Gazprom. Today, we will review Gazprom’s Power Generation Strategy. This Press Conference is attended by Denis Fyodorov, Head of Directorate at Gazprom and Director General of Gazprom Energoholding. I give the floor to Mr. Fyodorov, and then we will move on to your questions. DENIS FYODOROV: Good afternoon, dear colleagues. I will try to be brief in my presentation and then answer all of your questions. I would like to begin by emphasizing that 2017 was an anniversary year for us. It was exactly 10 years ago that Gazprom obtained its first power assets. The Gazprom Board of Directors approved the power generation development strategy. By now, it has been fully implemented and completed, and we are ready to put forward a new 10-year strategy for approval very soon. The projects implemented by Gazprom made it possible to create the country’s largest power holding company: controlling stakes were acquired in Mosenergo and TGC-1, in OGK-2 and OGK-6, which are now consolidated in a single company, as well as in MOEK. Today, we account for 16 per cent of all electricity produced in Russia and hold the lead in the national heat supply market. Our most remarkable success of recent years is MOEK’s transformation into a company with positive operating results. We already know that some banking organizations are showing interest in its bond issues, which means that the company has finally managed to show a consistently positive trend after several years of financial instability. -

Jsc Ogk-2 Annual Report 2017

JSC OGK-2 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 JSC OGK-2 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 This 2017 annual report (hereinafter referred to as the “Annual Report”) has been prepared using the information available to Joint-Stock Company “Second Wholesale Power Market Generating Company” (hereinafter, OGK-2, or the Company) at the time of its preparation. Some statements included in this Annual Report of the Company are forecasts for future events. Words such as “plans”, “will be”, “expected”, “will take place”, “estimates”, “will total”, “will occur”, and the like are forecasting by nature. Investors should not fully rely on the estimates and forecasts as they imply a risk of contradiction to reality. For this reason, the Company warns that the actual results or course of any events may significantly differ from forecast statements included in this annual report. Except as otherwise established by the applicable laws, the Company does not undertake to revise or confirm any expectations and estimates or publish updates and changes of forecast statements of the annual report as a result of any subsequent events or if new information becomes available. The information about the Company’s management staff is provided under the Federal Law No. 152-FZ “On Personal Data” dated July 27, 2006. 2 JSC OGK-2 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Table of Contents 1. INFORMATION ABOUT THE COMPANY ............................................................................. 5 ADDRESS BY CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS OF JSC OGK-2, DIRECTOR GENERAL OF GAZPROM ENERGOHOLDING LLC D.V. FEDOROV ..... 10 ADDRESS BY DIRECTOR GENERAL OF JSC OGK-2 S.A. ANANYEV ........................ 11 1.1. Business Model ....................................................................................................................................... 12 1.2. -

Company News SECURITIES MARKET NEWS

SSEECCUURRIIITTIIIEESS MMAARRKKEETT NNEEWWSSLLEETTTTEERR weekly Presented by: VTB Bank, Custody July 5, 2018 Issue No. 2018/24 Company News MTS owners elect board, nod to pay bonuses to management with shares On June 28, 2018 shareholders of major Russian mobile operator MTS elected the board of directors, changing its three members, and decided to pay remuneration to the board with stock instead of cash. The new members on the board are MTS President Alexei Kornya, who headed the company in March, Alexei Katkov, a managing partner at Sistema, MTS’ main shareholder, and independent director Wolfgang Schussel. MTS’ shareholders also approved a new wording of a statement on remuneration of the board members, which stipulates payments in shares, not in money. The board members will not sell the shares for three years. TGC-2 can buy Quadra for RUB 18 bln in September-October 2018 On June 29, 2018 it was reported that Russian power producer Territorial Generating Company-2 (TGC-2) was making due diligence of Quadra to buy it from Onexim of Mikhail Prokhorov in September-October for RUB 18 bln. Onexim bought 48.6% in Quadra, then known as TGC-4, in 2008 during a split of RAO UES of Russia, for RUB 26 bln. Onexim’s stake grew to 49.99% after that. Businessinform of Prokhorov owns 24.74% in the power producer and brokerage company Region 6.4%. A source said that TGC-2 plans to spin off some Quadra assets after the purchase, leaving only generation. Global Ports says appoints Delo Group’s Bychkov as new CEO On June 29, 2018 it was announced that Russian container terminal operator Global Ports appointed Vladimir Bychkov, an executive of one of companies of businessman Sergei Shishkaryov’s Delo Group, as CEO starting from July 16. -

ESG Ranking of Russian Companies 2020 (As of 11.11.2020)

ESG Ranking of Russian companies 2020 (as of 11.11.2020) Company Industry Sub-industry ESG Rank E Rank S Rank G Rank LUKOIL Oil&Gas Integrated Oil & Gas 1 3 10 2 SIBUR Holding Chemicals Petrochemicals 2 1 4 10 Passenger Russian Railways Transport Transportation, Ground 3 11 8 4 & Sea Wireless MTS Telecom Telecommunications 4 18 5 3 Services NLMK Metals&Mining Iron & Steel 5 6 2 16 Inter RAO Energy Electric Utilities 6 2 6 17 Integrated Rostelecom Telecom Telecommunications 7 17 12 8 Services Rosatom Energy Nuclear energy 8 8 23 5 SUEK Metals&Mining Coal 9 13 11 15 Sakhalin Energy Oil&Gas Integrated Oil & Gas 10 7 7 29 Gazprom Oil&Gas Integrated Oil & Gas 11 4 14 22 Severstal Metals&Mining Iron & Steel 12 24 3 11 Polyus Metals&Mining Gold 13 14 9 20 Non-Gold Precious ALROSA Metals&Mining 14 15 17 9 Metals & Minerals Sistema Holdings Holdings 15 20 15 13 Aeroflot Transport Airlines 16 26 1 27 FGC UES Energy Electric Utilities 17 12 30 1 RusHydro Energy Electric Utilities 18 5 16 26 Rosneft Oil&Gas Integrated Oil & Gas 19 9 22 18 Rosseti Energy Electric Utilities 20 10 28 6 Phosagro Chemicals Agricultural Chemicals 21 19 24 14 Specialty Mining & Rusal Metals&Mining 22 16 19 25 Metals NOVATEK Oil&Gas Integrated Oil & Gas 23 23 18 21 MMK Metals&Mining Iron & Steel 24 22 25 12 Oil & Gas Transportation TransNeft Oil&Gas 25 28 29 7 Services EVRAZ Metals&Mining Iron & Steel 26 29 20 24 Metalloinvest Metals&Mining Iron & Steel 27 21 21 31 TMK Metals&Mining Iron & Steel 28 25 27 28 Specialty Mining & Nornickel Metals&Mining 29 31 13 23 Metals Tatneft -

UNITING the ENERGY 2018 Annual Report ANNUAL REPORT 2018 of PSJC FEDERAL HYDROGENERATING COMPANY – RUSHYDRO, INCLUDING INFORMATION on SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

UNITING THE ENERGY 2018 Annual report ANNUAL REPORT 2018 OF PSJC FEDERAL HYDROGENERATING COMPANY – RUSHYDRO, INCLUDING INFORMATION ON SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT This Annual Report is preliminary approved by the Board of Directors on May 24, 2019, approved by decision of the Annual General Meeting of Shareholders on June 28, 2019 //COMPANY PROFILE PJSC RusHydro | Annual report 2018 CONTENT 10 28 62 146 214 Company Strategic Our Corporate Appendices profile review performance governance 4 Responsibility statement 12 About Company 30 Markets served 64 Economics and finance 148 Corporate governance 216 Auditor’s opinion 4 Information on the report 12 RusHydro’s background 32 Strategy of RusHydro Group 74 Production and sales 153 Shareholders and investors 220 Opinion on Public Assurance 6 Message from the Chairman 17 Key awards and ratings 36 Key performance indicators 106 Innovations 160 Governing bodies 222 Defining materiality and creating of the Board of Directors a materiality matrix 18 Key figures 40 Investment activities 112 Procurement 180 Executive bodies 8 Message from the Chairman of 224 GRI content index 20 Structure of Rushydro Group 51 Sustainable development 117 HR and social policy 187 Audit and control the Management Board – General 229 Tables of compliance with Director 22 Geographical spread Environmental protection 199 Risk management 131 International Integrated 24 Business model 210 Report on remuneration Reporting Framework of the governing and control 230 Glossary bodies 232 List of abbreviations 232 Feedback questionnaire 233 Contacts 2 3 //COMPANY PROFILE PJSC RusHydro | Annual report 2018 Comparability with the ↗ RusHydro’s Information Policy information expanded from 48 to 60 RESPONSIBILITY previous annual reports Regulations; companies. -

4/2019 Results of 2019 PDF 19.6 Mbyte

Results: CONTENTS 6 7 10 4 From the first person 17 PHOTO EVENT 26 Pilot project Alexander Slavinsky: Fruitful cooperation Superconductor Strategy of development with Indian technologies are opening in action partners new horizons for the ‘We have set a goal to manufacture products Russian energy sector that are not only competitive on the Russian market but in the entire world’. 18 Export Tests in India 30 Power Industry of Russia 6 Industry Events Successfully Completed 32 Point on the map 8 Photo Event Izolyator HV and UHV bushings have passed Geography of testing at the Central Power Research Institute Cooperation in 2019 PGIF 2019 in India 10 RNC CIGRE Events 20 Export 36 Electrical Engineering 2019: milestones, facts Ambitions goals 40 Marketing in the international 14 Feature story Yaroslav SEDOV: arena ‘As we further expand our presence, we Ivan PANFILOV: Deliveries of bushings to the power grids of assessed markets in such countries as Russian — India: the countries of the world Malaysia, South Korea and Saudi Arabia’. wide step integration and cooperation 22 Export 42 Word experience The Russian-Indian joint venture Massa Developing Japan: introduction Izolyator Mehru Pvt. Ltd for production of high voltage bushings in India has been Cooperation With of RES and development registered CIS Countries of market mechanisms 2 18 14 26 56 58 44 Technologies 52 Pulse of the company and innovation Julia TURINA: “Our staff development program received a high Konstantin SIPILKIN: praise from the company management and the A start into the big future entire team” “RIN bushings hit the mass production. -

PDF Version SUEK at a Glance

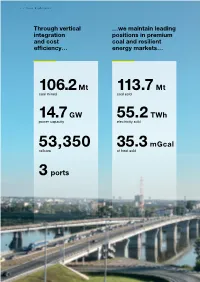

~ / Year highlights Through vertical …we maintain leading integration positions in premium and cost coal and resilient efficiency… energy markets… 106.2 Mt 113.7 Mt coal mined coal sold 14.7 GW 55.2 TWh power capacity electricity sold 53,350 35.3 mGcal railcars of heat sold 3 ports …and deliver ...underpinned robust EBITDA, by a culture stable margins focused and cash flows... on sustainability $2,115m 9 Mt EBITDA CO2 saved annually by our co-generation of heat and electricity 28% EBITDA margin -2% emissions CO, NOx, SO2 in Energy segment $2,059m $26m operating cash flow invested in social programmes ~ / SUEK at a glance Advanced coal and energy company Vertically Integration and control of the entire cycle, from production integrated and to customer delivery: cost-efficient 32% 96% For more details, see Business model of coal consumed of heat produced on pages 12–13. by our own power plants in the co-generation cycle >80% 80% of coal delivered of coal transhipped by managed railcars through our own ports Maintaining Mt 2019 Glencore 93.5 leading positions BHP Billiton 66.8 in premium coal Anglo American 62.0 and resilient SUEK 53.8 energy market Bumi 52.7 Adaro 46.0 A top- For more details, see Market 5 Yancoal 35.6 fundamentals and SUEK coal supplier 31.3 on pages 16–21. Kuzbassrazrezugol to the international Banpu 27.1 coal market Kideco 24.5 Source: Company data. SUEK Integrated Report Delivering Increased share of low-volatile revenue, $m robust EBITDA, Export revenue from sales of coal stable margins Revenue from sales of coal and services in Russia and cash flows 5,352 Energy segment revenue 4,526 For more details, 4,471 see Financial review 2,933 2,972 Logistic segment revenue (external) on pages 56–59.