Crown Copyright Catalogue Reference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes to the Introduction I the Expansion of England

NOTES Abbreviations used in the notes: BDEE British Documents of the End of Empire Cab. Cabinet Office papers C.O. Commonwealth Office JICH journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History Notes to the Introduction 1. J. C. D. Clark, '"The Strange Death of British History?" Reflections on Anglo-American Scholarship', Historical journal, 40: 3 (1997), pp. 787-809 at pp. 803, 809. 2. S. R. Ashton and S. E. Stockwell (eds), British Documents of the End of Empire, series A, vol. I: Imperial Policy and Colonial Practice, 1925-1945, part I: Metro politan Reorganisation, Defence and International Relations, Political Change and Constitutional Reform (London: HMSO, 1996), p. xxxix. Some general state ments were collected, with statements on individual colonies, and submitted to Harold Macmillan, who dismissed them as 'scrappy, obscure and jejune, and totally unsuitable for publication' (ibid., pp. 169-70). 3. Clark,' "The Strange Death of British History"', p. 803. 4. Alfred Cobban, The Nation State and National Self-Determination (London: Fontana, 1969; first issued 1945 ), pp. 305-6. 5. Ibid., p. 306. 6. For a penetrating analysis of English constitutional thinking see William M. Johnston, Commemorations: The Cult of Anniversaries in Europe and the United States Today (New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers, 1991). 7. Elizabeth Mancke, 'Another British America: a Canadian Model for the Early Modern British Empire',]ICH, 25: 1 (January 1997), pp. 1-36, at p. 3. I The Expansion of England 1. R. A. Griffiths, 'This Royal Throne ofKings, this Scept'red Isle': The English Realm and Nation in the later Middle Ages (Swansea, 1983), pp. -

From Behind Closed Doors to the Campaign Trail: Race and Immigration in British Party Politics, 1945-1965 Nicole M

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 11-14-2008 From Behind Closed Doors to the Campaign Trail: Race and Immigration in British Party Politics, 1945-1965 Nicole M. Chiarodo University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Chiarodo, Nicole M., "From Behind Closed Doors to the Campaign Trail: Race and Immigration in British Party Politics, 1945-1965" (2008). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/174 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Behind Closed Doors to the Campaign Trail: Race and Immigration in British Party Politics, 1945-1965 By Nicole M. Chiarodo A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Graydon Tunstall, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Kathleen Paul, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Fraser Ottanelli, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 14, 2008 Keywords: great britain, race relations, citizenship, conservative, labour © Copyright 2008, Nicole M. Chiarodo TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract i Introduction 1 In the Aftermath of War 9 The 1950s Conservative Government 21 Towards Restriction and Into the Public Gaze 34 Smethwick and After 46 Conclusion 59 Works Cited 64 i From Behind Closed Doors to the Campaign Trail: Race and Immigration in British Party Politics, 1945-1965 Nicole M. -

This Item Was Submitted to Loughborough's Institutional

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository This item was submitted to Loughborough’s Institutional Repository by the author and is made available under the following Creative Commons Licence conditions. For the full text of this licence, please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ 1 ‘Images of Labour: The Progression and Politics of Party Campaigning in Britain’ By Dominic Wring Abstract: This paper looks at the continuities and changes in the nature of election campaigns in Britain since 1900 by focusing on the way campaigning has changed and become more professional and marketing driven. The piece discusses the ramifications of these developments in relation to the Labour party's ideological response to mass communication and the role now played by external media in the internal affairs of this organisation. The paper also seeks to assess how campaigns have historically developed in a country with an almost continuous, century long cycle of elections. Keywords: Political marketing, British elections, Labour Party, historical campaigning, party organisation, campaign professionals. Dominic Wring is Programme Director and Lecturer in Communication and Media Studies at Loughborough University. He is also Associate Editor (Europe) of this journal. Dr Wring is especially interested in the historical development of political marketing and has published on this in various periodicals including the British Parties and Elections Review, European Journal of Marketing and Journal of Marketing Management. 2 Introduction. To paraphrase former General Secretary Morgan Philips’ famous quote, Labour arguably owes more to marketing than it does to Methodism or Marxism. -

The Daily Egyptian, April 03, 1965

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC April 1965 Daily Egyptian 1965 4-3-1965 The aiD ly Egyptian, April 03, 1965 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_April1965 Volume 46, Issue 116 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, April 03, 1965." (Apr 1965). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1965 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in April 1965 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'Blue Horizon' by Hans Jaenisch 'Spirit of New Serlin' CominSt -see photos, stories on pages 2 and 3 Also Inside Spanish Column Discusses tEl Futbol'-page 2 SOUTHERH 'LLIHOIS UHIVERSITY Carbondale, Illinois Ezra Pound as Sculptor-book review on page 4 11-:"· Volume 46 Saturday, April 3, 1965 Number N!J An Invitation From the Mayor of Berlin MMd! 28, '1965 My VeM F,uend~: I ex-tend a COlc.ckai. .tnv~on -tltltough YOM c.ampU6 netv.6papeJL, The Va.i..1.Jj Egyptian, nOll. aU nacCLUlj membe1L6 and ,~-tudent6 who can do .60 to v.w.t-t -the exil.tbilion "sp.uu..t 06 New 6eMA.n .ttt Pa.in:ting and Scuiptulte" to be hdd a:t -the Un.i..veM.i..:ttj Ga.UeJt.i..e..~ 06 So(u:heItH IlliHo.w Uru.veM.tty, ApJt.i...f 6-'2.7. The ugh-t pa.i..n.te.1L6 and .6.tx -6c.u.ipto.1L6 who.:,e WOItM Me .tnc.1uded .tn tl!.-W exhib-i.-Uot! Me I!.epltuen-tative 06 my city lIJ!uch hCUl a .fong and pltoud tltack·Uon CUl a c.CLUUltai. -

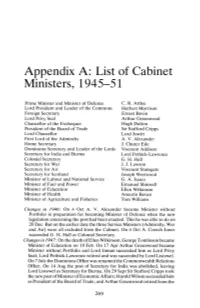

Appendix A: List of Cabinet Ministers, 1945-51

Appendix A: List of Cabinet Ministers, 1945-51 Prime Minister and Minister of Defence C. R. Attlee Lord President and Leader of the Commons Herbert Morrison Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin Lord Privy Seal Arthur Greenwood Chancellor of the Exchequer Hugh Dalton President of the Board of Trade Sir Stafford Cripps Lord Chancellor Lord Jowitt First Lord of the Admiralty A. V. Alexander Home Secretary J. Chuter Ede Dominions Secretary and Leader of the Lords Viscount Addison Secretary for India and Burma Lord Pethick-Lawrence Colonial Secretary G. H. Hall Secretary for War J. J. Lawson Secretary for Air Viscount Stansgate Secretary for Scotland Joseph Westwood Minister of Labour and National Service G. A. Isaacs Minister of Fuel and Power Emanuel Shinwell Minister of Education Ellen Wilkinson Minister of Health Aneurin Bevan Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries Tom Williams Changes in 1946: On 4 Oct A. V. Alexander became Minister without Portfolio in preparation for becoming Minister of Defence when the new legislation concerning the post had been enacted. This he was able to do on 20 Dec. But on the earlier date the three Service Ministers (Admiralty, War and Air) were all excluded from the Cabinet. On 4 Oct A. Creech Jones succeeded G. H. Hall as Colonial Secretary. Changes in 1947: On the death of Ellen Wilkinson, George Tomlinson became Minister of Education on 10 Feb. On 17 Apr Arthur Greenwood became Minister without Portfolio and Lord Inman succeeded him as Lord Privy Seal; Lord Pethick-Lawrence retired and was succeeded by Lord Listowel. On 7 July the Dominions Office was renamed the Commonwealth Relations Office. -

Harold Wilson, Lyndon B Johnson and Anglo-American Relations 'At the Summit', 1964-68 Colman, Jonathan

www.ssoar.info A 'special relationship'? Harold Wilson, Lyndon B Johnson and Anglo-American relations 'at the summit', 1964-68 Colman, Jonathan Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Colman, J. (2004). A 'special relationship'? Harold Wilson, Lyndon B Johnson and Anglo-American relations 'at the summit', 1964-68.. Manchester: Manchester Univ. Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-271135 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de A ‘special relationship’? prelims.p65 1 08/06/2004, 14:37 To Karin prelims.p65 2 08/06/2004, 14:37 A ‘special relationship’? Harold Wilson, Lyndon B. Johnson and Anglo- American relations ‘at the summit’, 1964–68 Jonathan Colman Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave prelims.p65 3 08/06/2004, 14:37 Copyright © Jonathan Colman 2004 The right of Jonathan Colman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance -

Bibliography

Bibliography All the reports by House of Commons (HC) select committees listed below were published by the Stationery Office or its predecessor organisation, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, during the period of the parliamentary session indicated (for example, ‘HC 2006–07’). Governmental success and failure Graham T. Allison, Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1971) Richard Bellamy and Antonino Palumbo, eds, From Government to Governance (Aldershot, Hants: Ashgate 2010) Mark Bovens and Paul ’t Hart, Understanding Policy Fiascoes (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1996) Mark Bovens, Paul ’t Hart and B. Guy Peters, eds, Success and Failure in Public Governance: A Comparative Analysis (Cheltenham, Glos.: Edward Elgar, 2001) Annika Brändström, Fredrik Bynander and Paul ’t Hart, “Governing by Looking Back: Historical Analogies and Crisis Management”, Public Administration 82:1 (2004) 191–210 David Braybrooke and Charles E. Lindblom, A Strategy of Decision: Policy Evaluation as a Social Process (New York: Free Press of Glencoe, 1963) Martha Derthick, New Towns in Town: Why a Federal Program Failed (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1972) Norman Dixon, On the Psychology of Military Incompetence (London: Jonathan Cape, 1976) bibliographY William D. Eggers and John O’Leary, If We Can Put a Man on the Moon . .: Getting Big Things Done in Government (Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press, 2009) Ewen Ferlie, Laurence E. Lynn Jr and Christopher Pollitt, eds,The Oxford Handbook of Public Management (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005) Matthew Flinders, “The Politics of Public-Private Partnerships”,British Journal of Politics and International Relations 7:2 (2005) 215–39 Pat Gray and Paul ’t Hart, eds, Public Policy Disasters in Western Europe (London: Routledge, 1998) Michael Hill, The Public Policy Process, 5th edn (Harlow, Essex: Pearson, 2009) Albert Hirschman, “The Principle of the Hiding Hand”,Public Interest, no. -

By-Election Rebuffs and After

THE ECONOMIC WEEKLY ANNUAL NUMBER FEBRUARY 1965 From the London End By-Election Rebuffs and After Patrick Gordon Walker's dramatic defeat at Leyton is not the only by-election rebuff that the Labour Govern ment has suffered. At Nuneaton, another safe constituency, the Labour majority was halved at the election held to find Frank Cousins a seat in the Commons. The Liberals have not been slow to smell their opportunity. Jo Grimond has warned that "if Wilson wants to stay in office he really must start doing things which appeal to a wider public than the hard-core of the left- wing socialist voters". So the question is: with his majority reduced to three, wilt Harold Wilson trim his policies and seek an arrangement with the Liberals? THE dramatic defeat of Patrick pared with the 50.3 per cent votes the the margin has been declining since Gordon Walker at the Leyton by- Labour candidate received at the November (when Labour was 11,5 per election came as a complete surprise, General Election, at the by-election he cent ahead) but the Opinion Polls, not only to the Labour Party, but to received only 42.4 per cent while the Leyton and Nuneaton notwithstanding, the Conservatives as well. Naturally, Conservative candidate increased his still suggest that the country is inclined of course, the Labour Party had not share from 33.5 per cent to 42,9 per to support the Government. expected that Gordon Walker — a cent, with the Liberal percentage stranger to the constituency — would dropping from 16.2 per cent to 13.9 The Race Issue be able to poll the majority that the per cent. -

1 the Diary of Michael Stewart As British Foreign Secretary, April-May

The Diary of Michael Stewart as British Foreign Secretary, April-May 1968 Edited and introduced by John W. Young, University of Nottingham. The Labour governments of 1964-70 are probably the best served of all post-war British administrations in terms of diaries being kept by ministers.1 In the mid-1970s a very detailed, three volume diary of the period was published by Richard Crossman, after a lengthy court battle over the legality of such revelations, and this was followed in 1984 by a substantial single volume of diaries from Barbara Castle. Both were members of Harold Wilson’s Cabinet throughout the period. Then Tony Benn, a Cabinet member from 1966 to 1970, published two volumes of diaries on these years in the late 1980s.2 However, these were all on the left-wing of the party giving, perhaps, a skewed view of the debates at the centre of government. To achieve a balanced perspective more diary evidence from the centre and right of the Cabinet would be welcome. At least one right-wing minister, Denis Healey, kept a diary quite regularly and this has been used to help write both a memoir and a biography. But the diary itself remains unpublished and the entries in it evidently tend to be short and cryptic.3 Patrick Gordon Walker, an intermittent Cabinet member and a right-winger, kept a diary only fitfully during the government.4 But the diary of Michael Stewart, a party moderate has now been opened to researchers at Churchill College Archive Centre in Cambridge. This too is restricted in its time frame but it casts fresh light on a short, significant period in the Spring of 1968 when the government seemed on the brink of collapse and Stewart was faced with several difficult challenges as Foreign Secretary. -

The IMF Crisis, 1976 Transcript

The IMF Crisis, 1976 Transcript Date: Tuesday, 19 January 2016 - 6:00PM Location: Museum of London 19 January 2016 The IMF Crisis of 1976 Professor Vernon Bogdanor Ladies and gentlemen, this is the third lecture in a series on post-War political crises, and this lecture is on the 1976 crisis when Britain was forced to borrow money from the IMF, the International Monetary Fund, and in return, to allow IMF supervision of its economic policies. The then-Labour Government was divided on its response to the IMF terms and there was a long Cabinet battle before they were accepted, so the crisis was both an economic one and a political one. It has seemed for many to be a watershed, both in economics and in politics. In economic policy, it seemed there was a shift away from Keynesian methods of economic management, that is, the fine-tuning of the economy to control instability, inflation and unemployment, towards monetarism, which involved accepting a higher level of unemployment. But it was also a political, and in a sense an ideological, crisis because it seemed to be a crisis for the British version of social democracy, which relied on high levels of public spending to sustain the welfare state, and it prefigured the rise of Thatcherism and the long period of Conservative dominance which began in 1979. The crisis ended the post-War consensus on economic policy and prefigured the growth of a new consensus based around the idea of a limited state, so I think the crisis casts a shaft of light on the whole evolution of post-War economic policy. -

British History Outlines the Labour Governments 1964

Pre-U, Paper 1c: British History Outlines The Labour Governments 1964-70 Harold Wilson, and his governments, had a pretty mixed reputation at the time and that has been the case ever since. In part, that was because successful Labour leaders who occupy the centre-left of British politics (like Blair too) tend to be despised from two sides. In the first place, Conservatives find it very easy to viscerally hate them: many hated Wilson with a passion. That passion was, ironically, matched on the left, for whom Labour governments were, always, a disappointment. Wilson remains hard to pin down, a bit like a Lloyd George, and is often held to have had no fixed abode, no core beliefs or ideology. There is some element of truth in this. The quip he is remembered for is that ‘a week is a long time in politics’. He was certainly more of a fixer than visionary. But that was, in part, determined by circumstance. The visionary stuff had been done in 1945. The terms of the post-war consensus had been set. Like Macmillan before him, his primary task was managerial The 1964-66 government had a majority of 4 The government inherited very serious financial and economic problems, which would culminate in the devaluation of sterling in 1967 Labour had been bitterly divided in the ‘fifties. Gaitskell had seen off the hard left, but Wilson still led a party prone to division. His cabinet was made up of some highly capable men (and Barbara Castle), but it was also one particularly prone to divisions over policy, personality and ambition. -

Patrick Wall, Julian Amery, and the Death and Afterlife of the British Empire

Nothing New Under the Setting Sun: Patrick Wall, Julian Amery, and the Death and Afterlife of the British Empire by Frank Fazio B.A. in History, May 2018, Villanova University A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 17, 2020 Thesis directed by Dane Kennedy Elmer Louis Kayser Professor of History Table of Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................1 2. Castles Made of Sand: The Rise and Fall of the Central African Federation, 1950- 1963 .....................................................................................................................................7 3. “Wrapped Up in the Union Jack”: UDI and the Right-Wing Reaction, 1963-1980 ....32 4. Stoking the Embers of Empire: The Falklands and the Half-Life of Empire, 1968- ...57 5. Bibliography .....................................................................................................................77 ii Introduction After being swept out of Parliament in the winter of 1966, Julian Amery set about writing his memoirs. Son of a famous father and son-in-law of a former Prime Minister, the 47-year-old felt sure that this political setback was merely a bump in the road. Therefore, rather than risking offending his once and future peers by writing “with candour,” Amery chose to write his memoirs about his early life and service during the Second World War.1 True to his word, Amery concluded the first and only volume of his memoirs with his election to Parliament in 1950. However, his brief preface betrayed a crucial aspect of how he perceived Britain’s place in the world in the late 1960s.